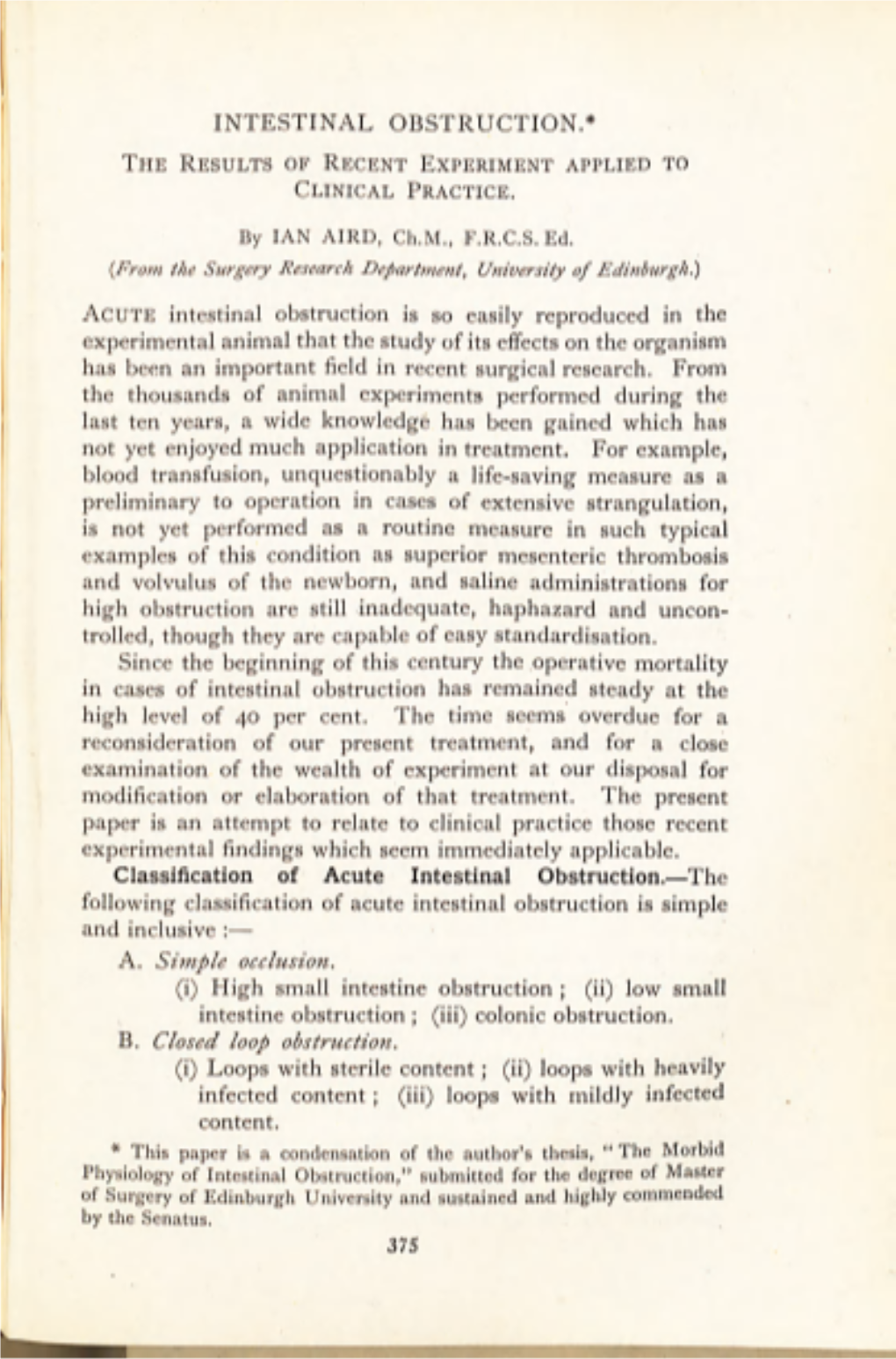

Intestinal Obstruction.*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of Oxysterol Effects on Membrane Bilayers Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations Brett Olsen Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) January 2010 An Examination of Oxysterol Effects on Membrane Bilayers Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations Brett Olsen Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Olsen, Brett, "An Examination of Oxysterol Effects on Membrane Bilayers Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations" (2010). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 420. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/420 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Washington University in Saint Louis Division of Biology and Biological Sciences Program in Molecular and Cellular Biology Dissertation Examination Committee: Nathan Baker, Chair Douglas Covey Katherine Henzler-Wildman Garland Marshall Daniel Ory Paul Schlesinger An Examination of Oxysterol Effects on Membrane Bilayers Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations by Brett Neil Olsen A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 Saint Louis, Missouri Acknowledgments I would like to thank my doctoral adviser Nathan Baker, whose guidance and advice has been essential to my development as an independent researcher, and whose confidence in my abilities has often surpassed my own. Thanks to my experimental collaborators at Washington University: Paul Schlesinger, Daniel Ory, and Doug Covey, without whom this work never would have been begun. -

C1orf32 Fused to the Fc Fragment for the Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis, Rheumatoid Arthritis and Other Autoimmune Disorders

(19) TZZ¥ Z _ T (11) EP 3 202 415 A2 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 09.08.2017 Bulletin 2017/32 A61K 38/17 (2006.01) A61P 25/28 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 17161149.4 (22) Date of filing: 30.06.2011 (84) Designated Contracting States: • ROTMAN, Galit AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB 46725 Herzliya (IL) GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO • LEVINE, Zurit PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR 46725 Herzliya (IL) • MILLER, Stephen D. (30) Priority: 30.06.2010 US 360011 P Chicago, IL Illinois 60611 (US) • PODOJIL, Joseph R. (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in Chicago, IL Illinois 60611 (US) accordance with Art. 76 EPC: 11748719.9 / 2 588 123 (74) Representative: Fuchs Patentanwälte Partnerschaft mbB (71) Applicant: Compugen Ltd. Westhafenplatz 1 5885849 Holon (IL) 60327 Frankfurt am Main (DE) (72) Inventors: Remarks: • HECHT, Iris This application was filed on 15-03-2017 as a Tel Aviv (IL) divisional application to the application mentioned under INID code 62. (54) C1ORF32 FUSED TO THE FC FRAGMENT FOR THE TREATMENT OF MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS, RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS AND OTHER AUTOIMMUNE DISORDERS (57) This invention relates to a protein C1ORF32 and development, including but not limited to as immune its variants and fragments and fusion proteins thereof, modulatorsand for immunetherapy, including for autoim- and methods of use therof for immunotherapy, and drug mune disorders. EP 3 202 415 A2 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 3 202 415 A2 Description FIELD OF THE INVENTION 5 [0001] This invention relates to a novel protein, and its variants, fragments and fusion proteins thereof, and methods of use therof for immunotherapy, and drug development. -

A Comparison of the Potential Unfavorable Effects Of

Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., 72 (12), 3128–3133, 2008 A Comparison of the Potential Unfavorable Effects of Oxycholesterol and Oxyphytosterol in Mice: Different Effects, on Cerebral 24S-Hydroxychoelsterol and Serum Triacylglycerols Levels y Hyun-jung BANG, Chiyo ARAKAWA, Michihiro TAKADA, Masao SATO, and Katsumi IMAIZUMI Laboratory of Nutrition Chemistry, Division of Bioresource and Bioenvironmental Sciences, Graduate School, Kyushu University, Fukuoka 812-8581, Japan Received April 16, 2008; Accepted August 9, 2008; Online Publication, December 7, 2008 [doi:10.1271/bbb.80256] Sterol oxidation products derived from cholesterol Our previous study indicated that oxidation products and phytosterol are formed during the processing and derived from cholesterol and plant sterols accumulated storage of foods. The objective of the present study was to a considerable extent in the tissues of apolipopro- to assess the potential unfavorable effects of oxysterols tein E deficient mice, but the atherosclerotic severity in in mice. C57BL/6J mice were fed an AIN-93G-based the aortic value of the mice fed the oxysterols was not diet containing 0.2 g/kg of oxycholesterol or oxyphyto- different from that in the oxysterol-free group.7,8) Our sterol for 4 weeks. The most abundant oxysterol in the findings are different from those showing a role of diet was 7-ketosterol, but -epoxycholesterol, -epox- dietary oxycholesterols in the development of athero- ycholesterol, or 7 -hydroxyphytosterol, and 7 -hydro- sclerosis in experimental animals.10,11) Very few data xyphytosterol were more prominent than 7-ketosterol in except those from Tomoyori et al.8) are available on the the serum and liver respectively. -

Deleterious Effects of Food Habits in Present Era Aliya Siddiqui1*And Naga Anusha P2 1Department of Biotechnology, Chaitanya P.G

erg All y & of T l h a e n r r a Siddiqui and Anusha. J Aller Ther 2012, 3:1 p u y o J Journal of Allergy & Therapy DOI: 10.4172/2155-6121.1000114 ISSN: 2155-6121 Review Article Open Access Deleterious Effects of Food Habits in Present Era Aliya Siddiqui1*and Naga Anusha P2 1Department of Biotechnology, Chaitanya P.G. College, Kakatiya University, India 2 Department of Biotechnology, Sri Y.N. College, Andhra University, India Abstract Food is any substance usually of plant or animal origin consumed to provide nutritional support for the body. It contains essential nutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals etc. Consuming healthy food like fresh fruits and vegetables gives the body strength and power to stay healthy without any infections and diseases. In spite of knowing the value of healthy food, most of the people prefer fast food which affects their health and lives. This Review Article deals with the Food and its Impact on Human Health, what are the side effects when food is taken in excess amounts and what might happens when it is not supplied to the body in enough quantities, what could be the problems which most of the people face if fast food or junk food is consumed in large or excess quantities. As fast food culture is an emerging trend among the younger generation and most of them may suffer with food allergies and various health problems when consumed on a regular basis. Fast food has become a prominent feature of the diet for most of the people in United States and increasing, throughout the world. -

Method Development for Valid High-Resolution Profiling Of

Method development for valid high‐resolution profiling of mitochondria and Omics investigation of mitochondrial adaptions to excess energy intake and physical exercise Dissertation der Mathematisch‐Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) vorgelegt von Lisa Claudia Charlotte Kappler aus Weingarten Tübingen 2018 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung der Mathematisch‐Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen. Tag der mündlichen Qualifikation: 27.03.2018 Dekan: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Rosenstiel 1. Berichterstatterin: Prof. Dr. Carolin Huhn 2. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Rainer Lehmann Over the long term, symbiosis is more useful than parasitism. More fun, too. Ask any mitochondria. ‐Larry Wall‐ Scopes and aims of the thesis Index 1 SCOPES AND AIMS OF THE THESIS .............................................................................. 1 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 2 2.1 Insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes ................................................................................................. 2 2.1.1 Diet and physical activity ...................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Mitochondria, structure and function ................................................................................................. 3 2.2.1 Function of -

The Role of Antioxidants Supplementation in Clinical Practice: Focus on Cardiovascular Risk Factors

antioxidants Review The Role of Antioxidants Supplementation in Clinical Practice: Focus on Cardiovascular Risk Factors Vittoria Cammisotto 1,* , Cristina Nocella 2,*, Simona Bartimoccia 2, Valerio Sanguigni 3,4 , Davide Francomano 3, Sebastiano Sciarretta 5,6, Daniele Pastori 2 , Mariangela Peruzzi 5,7, Elena Cavarretta 5,7 , Alessandra D’Amico 8, Valentina Castellani 2, Giacomo Frati 5,6 , Roberto Carnevale 5,7,* and SMiLe Group 9,† 1 Department of General Surgery and Surgical Specialty Paride Stefanini, Sapienza University of Rome, 00185 Rome, Italy 2 Department of Clinical Internal, Anesthesiological and Cardiovascular Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome, 00185 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (S.B.); [email protected] (D.P.); [email protected] (V.C.) 3 Unit of Internal Medicine and Endocrinology, Madonna delle Grazie Hospital, Velletri, 00049 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (V.S.); [email protected] (D.F.) 4 Department of Internal Medicine, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, 00133 Rome, Italy 5 Department of Medical-Surgical Sciences and Biotechnologies, Sapienza University of Rome, 04100 Latina, Italy; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (E.C.); [email protected] (G.F.) 6 Department of AngioCardioNeurology, IRCCS Neuromed, 86077 Pozzilli, Italy 7 Mediterranea, Cardiocentro, 80122 Napoli, Italy 8 Department of Movement, Human and Health Sciences, University of Rome “Foro Italico”, 00135 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 9 Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, Sapienza University of Rome, 04100 Latina, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (V.C.); [email protected] (C.N.); Citation: Cammisotto, V.; Nocella, [email protected] (R.C.) C.; Bartimoccia, S.; Sanguigni, V.; † Membership of the SMiLe Group is provided in the Acknowledgments. -

British Chemical Abstracts

BRITISH CHEMICAL ABSTRACTS A.-PURE CHEMISTRY MARCH, 1934. General, Physical, and Inorganic Chemistry. Theory of hyperfine structures. E. Fermi and Infra-red grating spectra and spectral series E. SEGRi: (Mem. R. Accad. d’ltalia Sci. fis., 1933, 4, (A1II, A11, He I and n, Zn I and II). F. Paschen 131—158).—A theoretical discussion of the hyperfine and R. Ritsciil (Ann. Physik, 1933, [v], 18 , 867— structure of the spectral lines of Li, Na, Cu, Ga, lib, 892).—A comprehensive analysis of the grating spec Cd, In, Cs, Ba, Au, Hg, Tl, Pb, and Bi. The theory trum of A in is made. With a specially luminous of the nuclear magnetic moment is discussed. hollow cathode arrangement new infra-red lines 0. J. W. beyond 1 ¡j. are tabulated and an extended analysis is Spectrum of atomic nitrogen, N I. D. Seeerian given for A11, He i and it, Zn i and rr. W. R. A. (Compt. rend., 1934, 198, 68—69).—An arc is struck Arc spectrum of silicon in the red and infra between parallel W wires 3 mm. diam. and 2—3 mm. red. C. C. Kiess (Bur. Stand. J. Res., 1933, 11, apart, N2 at the rate of 800—1000 litres per hr. being 775—782).—130 new lines have been measured in the passed around them. With a.c. of 46—50 amp. at arc spectrum of Si between 6125 and 11,290 A . These 110 volts the spectrum of N i is obtained (cf. A., 1929, include the strongest previously unidentified Fraun 1116; 1932, 103), and also two different continuous hofer line (6155 A.) and other solar spectral lines. -

Current Knowledge on the Mechanism of Atherosclerosis and Pro-Atherosclerotic Properties of Oxysterols Adam Zmysłowski* and Arkadiusz Szterk

Zmysłowski and Szterk Lipids in Health and Disease (2017) 16:188 DOI 10.1186/s12944-017-0579-2 REVIEW Open Access Current knowledge on the mechanism of atherosclerosis and pro-atherosclerotic properties of oxysterols Adam Zmysłowski* and Arkadiusz Szterk Abstract Due to the fact that one of the main causes of worldwide deaths are directly related to atherosclerosis, scientists are constantly looking for atherosclerotic factors, in an attempt to reduce prevalence of this disease. The most important known pro-atherosclerotic factors include: elevated levels of LDL, low HDL levels, obesity and overweight, diabetes, family history of coronary heart disease and cigarette smoking. Since finding oxidized forms of cholesterol – oxysterols – in lesion in the arteries, it has also been presumed they possess pro-atherosclerotic properties. The formation of oxysterols in the atherosclerosis lesions, as a result of LDL oxidation due to the inflammatory response of cells to mechanical stress, is confirmed. However, it is still unknown, what exactly oxysterols cause in connection with atherosclerosis, after gaining entry to the human body e.g., with food containing high amounts of cholesterol, after being heated. The in vivo studies should provide data to finally prove or disprove the thesis regarding the pro-atherosclerotic prosperities of oxysterols, yet despite dozens of available in vivo research some studies confirm such properties, other disprove them. In this article we present the current knowledge about the mechanism of formation of atherosclerotic lesions and we summarize available data on in vivo studies, which investigated whether oxysterols have properties to cause the formation and accelerate the progress of the disease. -

Annual Report 2005

Division of Surgical Research Annual Report 2005 Department of Surgery University Hospital Zurich Switzerland Division of Surgical Research Department of Surgery University Hospital Rämistrasse 100 CH - 8091 Zurich 2 Photo & Graphic, Division of Surgical Research Nico Wick and Carol De Simio Content Preface 5 1. Organisation 6 2. Research and Development 8 Cardiac Surgery 8 Tissue Engineering 8 Ischemia / Reperfusion Injury 12 Mechanical Circulatory Support 16 Robotic Surgery 18 Visceral & Transplantation Surgery 20 Hepatobiliary & Transplantation Surgery 20 Islet Cell Laboratory 28 Pancreatitis Research Laboratory 30 Colorectal Surgery Laboratory 33 Trauma Surgery 34 Trauma Immunology 34 Osteogenesis Laboratory 37 Innate Immunity Laboratory 40 Computer Assisted Trauma Surgery 43 Musculosceletal tissue conditioning 46 Plastic, Hand & Reconstructive Surgery 48 Tissue Engineering 48 Anti Aging 51 Thoracic Surgery 53 Transplantation Immunology 53 Tissue Engineering 60 Oncology 63 Surgical Intensive Care Units 67 3. Services 70 Surgical skill laboratories 70 Microsurgical laboratory 70 Histology 70 Photo and Graphic services 71 Administration 71 4. Events 72 5. Publications 73 6. Grants 75 7. Awards 78 4 Preface Dear Colleagues It is my pleasure to present to you the Annual Report 2005 of the Division of Surgical Research, Department of Surgery at the University Hospital Zurich. In the year 2005 we have undergone substantial administrative reorganisation Prof. Dr. med. and with the support of all members within the Division organisational problems Gregor Zünd, Head Division of could be solved quickly. The new facilities built in 2004 were successfully Surgical Research implemented in the daily routine and are highly appreciated by technicians and researchers. The research group of the Division of Surgical Intensive Care was integrated and could be provided with new laboratories. -

WO 2017/062816 A2 13 April 2017 (13.04.2017) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2017/062816 A2 13 April 2017 (13.04.2017) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, A61K 48/00 (2006.01) C07H 21/02 (2006.01) BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (21) International Application Number: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, PCT/US20 16/056068 KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (22) International Filing Date: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, 7 October 2016 (07. 10.2016) OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, (25) Filing Language: English TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (26) Publication Language: English ZW. (30) Priority Data: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 62/238,83 1 8 October 201 5 (08. 10.2015) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, (71) Applicant: IONIS PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, [US/US]; 2855 Gazelle Court, Carlsbad, CA 92010 (US). -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.410,155 B2 Collard Et Al

US00941 O155B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.410,155 B2 Collard et al. (45) Date of Patent: Aug. 9, 2016 (54) TREATMENT OF VASCULAR ENDOTHELIAL 5,491,084 A 2f1996 Chalfie et al. GROWTH FACTOR (VEGF) RELATED 35, A : 3: Sutter s al. DISEASES BY INHIBITION OF NATURAL 5.535.735 A 6/1996 di t ANTISENSE TRANSCRIPT TO VEGF 5.539,083 A 7/1996 Cookeral. 5,549,974 A 8, 1996 Holmes (71) Applicant: CuRNA, Inc., Miami, FL (US) 5,569,588 A 10/1996 Ashby et al. 5,576,302 A 11/1996 Cook et al. (72) Inventors: Joseph Collard, Delray Beach, FL (US); 5,593,853 A 1/1997 Chen et al. Olga Khorkova Sherman. Tequesta, FL 5,605,662 A 2f1997 Heller et al. g , led s 5,661,134 A 8, 1997 Cook et al. (US) 5,708, 161 A 1/1998 Reese 5,736,294 A * 4/1998 Ecker et al. ................... 435/375 (73) Assignee: CuRNA, Inc., Miami, FL (US) 5,739,119 A 4/1998 Galli et al. 5,739,311 A 4/1998 Lackey et al. (*)c Notice:- r Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5,849,9025,756,710 A 12/19985/1998 ArrowStein et et al. al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 5,891.725 A 4/1999 Soreqet al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 5,902,880 A 5/1999 Thompson 5,908,779 A 6/1999 Carmichael et al. (21) Appl. No.: 14/534,349 5,965,721 A 10/1999 Cook et al. -

Unknown Cholesterol Especially Hard on Heart

‘Unknown’ cholesterol in processed food poses big heart health risk Page 1 of 2 Breaking News on Food & Beverage Development - North America ‘Unknown’ cholesterol in processed food poses big heart health risk By Stephen Daniells, 21-Aug-2009 With all the focus on LDL (bad) cholesterol, a ‘virtually unknown’ form called oxycholesterol may pose the biggest heart health threat, say Chinese scientists. Scientists from the Chinese University of Hong Kong identified fried and processed food as the main sources of oxycholesterol in the diet, statements that may lead to louder calls to reformulate towards ‘healthier’ foods. "Total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), and the heart-healthy high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) are still important health issues," said lead researcher Zhen-Yu Chen, PhD. "Our work demonstrated that oxycholesterol boosts total cholesterol levels and promotes atherosclerosis ["hardening of the arteries"] more than non-oxidized cholesterol." Sources In an email communication with FoodNavigator, Dr Chen said: “Foods of animal origins contain cholesterol, which is stable at room temperature. However, it is susceptible to oxidation to produce the cholesterol oxidation products during heating, particularly, long frying and high temperature. “The amount of cholesterol consumed from diet is about 300-500 mg cholesterol per day per person while cholesterol oxidation products could reach up to 10 per cent total cholesterol in diet.” Oxycholesterol is produced in oxidised oils, particularly in the much-maligned trans-fatty acids and partially- hydrogenated vegetable oils. Health concerns, and the subsequent consumer reaction, have led many manufacturers to begin reformulating their products and reduce the trans-fat content, or eliminate it completely.