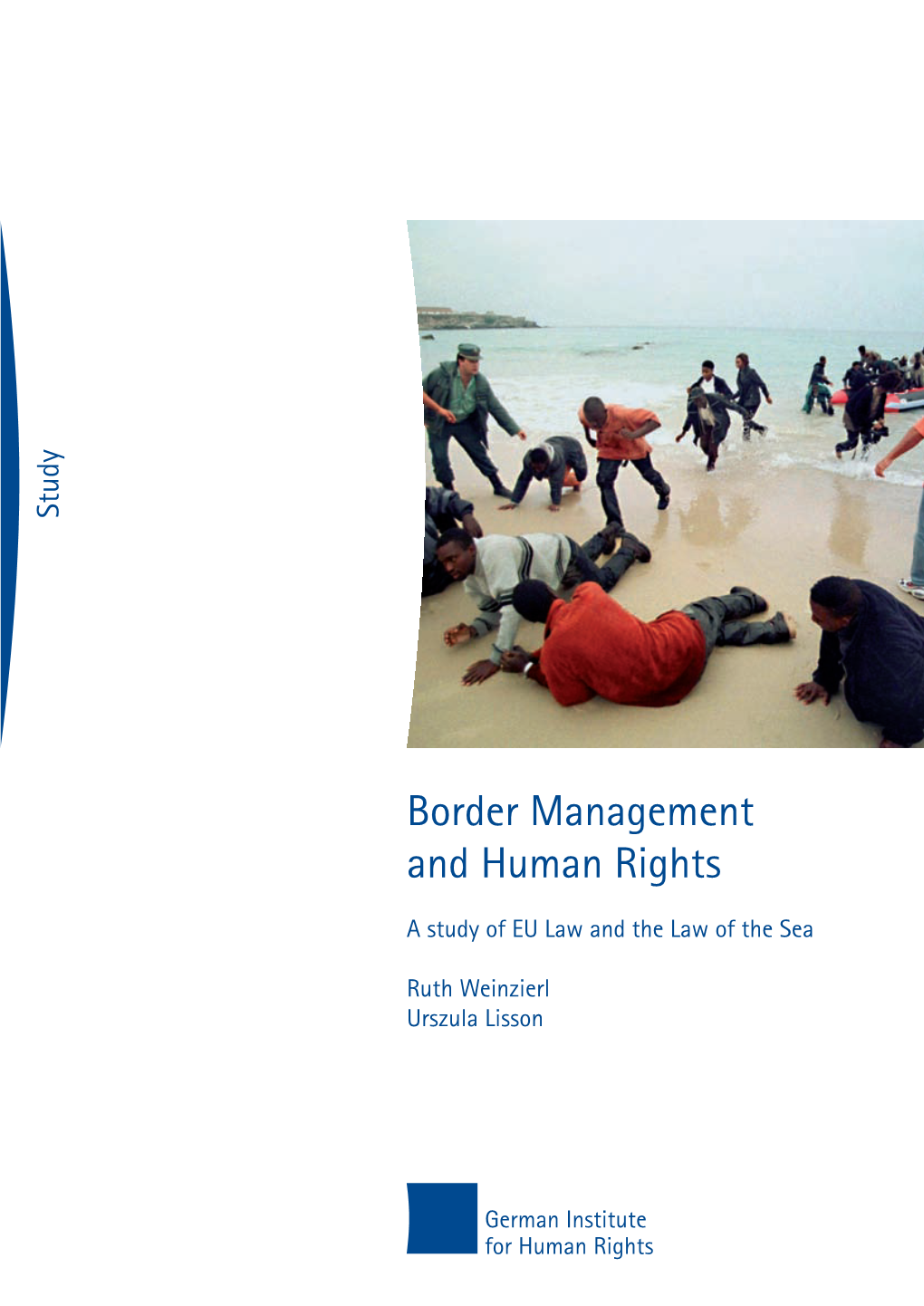

Border Management and Human Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commentary by Miriam Saage-Maaβ Vice Legal Director & Coordinator of Business & Human Rights Program European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights July 2012

How serious is the international community of states about human rights standards for business? commentary by Miriam Saage-Maaβ Vice Legal Director & coordinator of Business & Human Rights program European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights July 2012 Recent developments have shown one more time that the struggle for human rights is not only about the creation of international standards so that the rule of law may prevail. The struggle for human rights is also a struggle between different economic and political interests, and it is a question of power which interests prevail. 2011 was an important year for the development of standards in the field of business and human rights. In May 2011 the OECD member states approved a revised version of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, introducing a new human rights chapter. Only a month later the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) endorsed by consensus the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.1 These two international documents are both designed to provide a global standard for preventing and addressing the risk of business-related human rights violations. In particular, the UN Guiding Principles focus on the “State Duty to Protect” and the “Corporate Responsibility to Respect” in addition to the “Access to Remedy” principle. This principle seeks to ensure that when people are harmed by business activity, there is both adequate accountability and effective redress, both judicial and non-judicial. The Guiding Principles clearly call on states to ensure -

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE NATO in A

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE NATO in a changing world – Outdated Organization or Indispensable Alliance? Date Friday 6 and Saturday 7, March 2009 Venue Beletage of the Heinrich Böll Foundation Schumannstraße 8 10117 Berlin-Mitte Conference Languages All interventions will be simultaneously translated from English into German and vice versa. Project Management and Information Marc Berthold, Head of Department, Foreign and Security Policy, [email protected] , +49-30-285 34 393 Melanie Sorge, Political Consultant/Project Manager, [email protected] , +49-30-31163485, +49-179-871 60 93 NATO in a changing world – Outdated Organization or Indispensable Alliance? At its 60th anniversary summit in April 2009, NATO plans to launch a process to develop new security strategy. On this occasion, the Heinrich Böll Foundation will host an international conference on the future of the Alliance. After the end of the cold war, is NATO an outdated organization? What role should and can the organization take on in a plural world order? NATO – Rift or Bridge toward Russia? From the war in Afghanistan to the question of expanding towards Georgia and Ukraine and its new tensions with Russia: Is NATO ready for new challenges or is it rather at the brink of collapse? After the Iraq war, is NATO again a catalyst for the revitalization of a close trans-Atlantic partnership? Russia’s President Medvedev suggested a new Eurasian security organization ranging from Vancouver to Vladivostok. Does NATO have the potential to grow from a Western defense alliance into a comprehensive security pact that includes Russia? Or will it return to its original cause: keeping Russia in check? The Plural World Order: New Challenges with an old Security Architecture? There is tenuous agreement among NATO members that military means are not sufficient to address the major challenges of the day: solving the conflict in Afghanistan, preventing a new, nuclear arms race, and coping with climate change. -

Manning Policy Manual for Yachts

Manning Policy Manual Yachts engaged in trade 24m and over (Guidance for yachts not engaged in trade) Copyright © 2019 Cayman Islands Shipping Registry A division of MACI All Rights Reserved Table of Contents 1. Revision history ......................................................................................................................4 2. Introduction, purpose and application .................................................................................. 5 3. Applicable rules and regulations ...........................................................................................6 4. Definitions ...............................................................................................................................6 5. Maritime Labour Convention, 2006 .......................................................................................7 6. Seafarers’ Employment Agreement .......................................................................................8 7. LAP (Law & Administrative Procedures) ............................................................................. 8 8. English language ....................................................................................................................8 9. Recognition by endorsement of STCW Certificates of Competency .................................... 9 10. Seafarer’s Discharge Book .................................................................................................... 10 11. Ship’s Cooks......................................................................................................................... -

A Guide to Yacht Finance

A GUIDE TO YACHT FINANCE Those seeking to purchase a yacht or superyacht may often need to borrow the funds in order to buy it. But there are a number of other financially sound reasons to pursue this route, even if you have already amassed enough wealth to buy the asset in the first place. These include both practical and legal arguments ranging from running-cost benefits to tax advantages. In this article, Jonathan Hadley-Piggin provides a definitive guide to yacht finance. Jonathan Hadley-Piggin 020 3319 3700 [email protected] www.keystonelaw.co.uk REGISTRATION AND FLAG PREFERENCE A flag state is the country under whose laws a yacht is registered. This might be the country in which the owner lives or a ship registry in a country more synonymous with the complexities that surround charters and yacht ownership. Registration also grants the privilege and protection of flying the flag of that particular country. Every maritime nation, and even some land-locked countries such as Switzerland, has a system of ship registration that permits the registration of mortgages and other security interests. In 1993, a centralised UK registry replaced the system of individual registries in each major port. The centralised registry is divided into four separate parts, of which two are relevant to yachts: PART I PART III This is the main register consisting of merchant ships This is for small ships of under twenty-four metres and yachts alike. It is a full title register and has the in length. Known as the Small Ships Registry (abbr. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2018

INSIDE: l A century of U.S. congressional support for Ukraine – page 9 l Dallas community remembers Holodomor with exhibit – page 12 l Candle of Remembrance ceremonies in our communities – pages 16-17 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal W non-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXXVI No. 42 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2018 $2.00 Philanthropist/activist Ronald S. Lauder Moscow severs ties with Constantinople receives Metropolitan Sheptytsky Award over Ukraine Church’s independence by Mark Raczkiewycz KYIV – The Russian Orthodox Church is severing its relationship with the spiritual authority of the Orthodox Christian world following a Synod, or assembly of church hierarchy, that was held in Minsk on October 15. The decision could signal the widest rift in the religious world since the 1054 schism that divided western and eastern Christianity or the Reformation of 1517 when Roman Catholicism split into new Protestant divisions. It was in response to the move by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople four days earlier, after it also held a Holy Synod and announced it will proceed with UJE the process of giving Ukraine its own fully Mark Raczkiewycz 2018 Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky Award laureate Ronald S. Lauder, president of self-governed church. Archbishop Yevstratiy Zorya, spokesper- the World Jewish Congress (center), with James C. Temerty, board chairman of the Moscow reacted swiftly with Russian son for the Ukrainian Orthodox Church Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (left), and Borys Lozhkin, president of the Jewish President Vladimir Putin convening an – Kyiv Patriarchate, stands at the Confederation of Ukraine. emergency meeting of the Security Council entrance to St. -

Liberian Registry Maritime Brochure 2016

THE LIBERIAN REGISTRY DISCOVER THE ESTABLISHED IN WORLD’S LEADING SHIP REGISTRY 1948 PROVIDING FIRST-CLASS SERVICE FOR MORE THAN 65 YEARS The Liberian Registry is the world’s largest quality registry, renowned for excellence, efficiency, safety and innovative service. LIBERIA has earned international respect for its dedication to flagging the world’s safest and most secure vessels. The Liberian Registry is recognized at the top of every industry “white-list” including the International Maritime Organization and “Quality is never an the major Port State Control authorities such as the U.S. Coast Guard as well as accident; it is always the Paris and Tokyo MOU regimes. the result of high The Liberian Registry is administered by the Liberian International Ship and intention, sincere Corporate Registry (LISCR, LLC), a private U.S. owned and globally operated company. LISCR is internationally recognized for its professionalism and com- effort, intelligent mitment to reduce redundant workflow procedures in order to increase efficiency. direction and skillful The Registry is managed by industry professionals who understand the business of shipping and corporate structures. Its proficient administration is one of the execution; it represents most effective and tax efficient ship and corporate registries in the world. the wise choice of The Registry has experienced exponential growth in fleet size and registered ton- many alternatives.” nage throughout its long history. In recent years, the Liberian Registry has grown by approximately 80 million gross tons, twice the growth rate claimed by its nearest —William A. Foster competitor over the same period, establishing beyond dispute that Liberia is far and away the fastest growing quality ship registry. -

Wird Durch Die Lektorierte Fassung Ersetzt

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 18/4687 Vorabfassung - wird durch die lektorierte Fassung ersetzt. 18. Wahlperiode 22.04.2015 Antrag der Abgeordneten Cem Özdemir, Claudia Roth (Augsburg), Peter Meiwald, Annalena Baerbock, Marieluise Beck (Bremen), Dr. Franziska Brantner, Agnieszka Brugger, Ekin Deligöz, Uwe Kekeritz, Tom Koenigs, Dr. Tobias Lindner, Omid Nouripour, Manuel Sarrazin, Dr. Frithjof Schmidt, Jürgen Trittin, Doris Wagner, Luise Amtsberg, Matthias Gastel, Kai Gehring, Britta Haßelmann, Katja Keul, Renate Künast, Monika Lazar, Dr. Konstantin von Notz und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN Gedenken an den 100. Jahrestag des Völkermords an den Armeniern – Versöh- nung durch Aufarbeitung und Austausch fördern Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: Am 24.04.2015 jährt sich zum hundertsten Mal der Beginn des Völkermords an den ArmenierInnen im Osmanischen Reich. Der Deutsche Bundestag gedenkt der Opfer von Gewalt, Mord und Vertreibung. Bei Massakern und Todesmärschen starben in den Jahren 1915 bis 1918 hunderttausende ArmenierInnen. Die unfass- baren Geschehnisse dieser Jahre haben bis heute tiefe Wunden bei ArmenierInnen weltweit hinterlassen, die diese Jahre als Aghet („Katastrophe“) bezeichnen. Auch zehntausende Angehörige anderer christlicher Bevölkerungsgruppen im Osmanischen Reich, wie der AramäerInnen, AssyrerInnen, ChaldäerInnen und Pontos-GriechInnen, erfuhren damals Gewalt und Vertreibung. Das Deutsche Reich war 1915 enger Partner des Osmanischen Reiches. Obwohl deutsche Diplomaten und Missionare über den Völkermord berichteten, schritt die Regierung des Deutschen Reiches nicht ein und verhinderte sogar die Weiter- verbreitung entsprechender Informationen. Dennoch trugen die Berichte deut- scher Missionare dazu bei, die Weltöffentlichkeit über die Verbrechen an den Ar- menierInnen aufzuklären. Der Deutsche Bundestag beklagt die Taten der jungtürkischen Regierung des Os- manischen Reiches, die zur fast vollständigen Vernichtung der ArmenierInnen in Anatolien geführt haben. -

How Flags of Convenience Let Illegal Fishing Go Unpunished

OFF THE HOOK How flags of convenience let illegal fishing go unpunished A report produced by the Environmental Justice Foundation 1 OUR MISSION EJF believes environmental security is a human right. The Environmental Justice Foundation EJF strives to: (EJF) is a UK-based environmental and • Protect the natural environment and the people and wildlife human rights charity registered in England that depend upon it by linking environmental security, human and Wales (1088128). rights and social need 1 Amwell Street • Create and implement solutions where they are needed most London, EC1R 1UL – training local people and communities who are directly United Kingdom affected to investigate, expose and combat environmental www.ejfoundation.org degradation and associated human rights abuses Comments on the report, requests for further copies or specific queries about • Provide training in the latest video technologies, research and EJF should be directed to: advocacy skills to document both the problems and solutions, [email protected] working through the media to create public and political platforms for constructive change This document should be cited as: EJF (2020) • Raise international awareness of the issues our partners are OFF THE HOOK - how flags of convenience let working locally to resolve illegal fishing go unpunished Our Oceans Campaign EJF’s Oceans Campaign aims to protect the marine environment, its biodiversity and the livelihoods dependent upon it. We are working to eradicate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and to create full transparency and traceability within seafood supply chains and markets. We conduct detailed investigations into illegal, unsustainable and unethical practices and actively promote improvements to policy making, corporate governance and management of fisheries along with consumer activism and market-driven solutions. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Plenarprotokoll 14/171 Deutscher Bundestag Stenographischer Bericht 171. Sitzung Berlin, Freitag, den 18. Mai 2001 Inhalt: Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 13: Fraktion der CDU/CSU: EU-Richtlini- envorschlag zur Gewährung vorüber- Erste Beratung des von den Abgeordneten gehenden Schutzes im Falle eines Alfred Hartenbach, Hermann Bachmaier, Massenzustroms überarbeiten weiteren Abgeordneten und der Fraktion (Drucksache 14/5754) . 16734 A der SPD sowie den Abgeordneten Volker Beck (Köln), Grietje Bettin, weiteren Ab- in Verbindung mit geordneten und der Fraktion des BÜND- NISSES 90/DIE GRÜNEN eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Gesetzes zur Modernisie- Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 8: rung des Schuldrechts (Drucksache 14/6040) . 16719 A Antrag der Abgeordneten Ulla Jelpke, Carsten Hübner, weiterer Abgeordneter und Dr. Herta Däubler-Gmelin, Bundesministerin der Fraktion der PDS: EU-Richtlinienvor- BMJ . 16719 B schlag zu Mindeststandards in Asylver- Ronald Pofalla CDU/CSU . 16721 B fahren ist ein wichtiger Schritt für einen wirksamen Flüchtlingsschutz in Europa Volker Beck (Köln) BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜ- (Drucksache 14/6050) . 16734 B NEN . 16723 C Erwin Marschewski (Recklinghausen) Rainer Funke F.D.P. 16725 C CDU/CSU . 16734 C Dr. Evelyn Kenzler PDS . 16727 C Otto Schily, Bundesminister BMI . 16735 D Dirk Manzewski SPD . 16728 B Dr. Max Stadler F.D.P. 16738 C Dr. Andreas Birkmann, Minister (Thüringen) 16730 B Ulla Jelpke PDS . 16739 B Alfred Hartenbach SPD . 16732 A Marieluise Beck (Bremen) BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN . 16740 B Ulla Jelpke PDS . 16742 A Tagesordnungspunkt 15: Dr. Hans-Peter Uhl CDU/CSU . 16742 D a) Antrag der Abgeordneten Wolfgang Bosbach, Erwin Marschewski (Reck- Rüdiger Veit SPD . 16744 D linghausen), weiterer Abgeordneter und Erwin Marschewski (Recklinghausen) der Fraktion der CDU/CSU: EU-Richt- CDU/CSU . -

Islam Councils

THE MUSLIM QUESTION IN EUROPE Peter O’Brien THE MUSLIM QUESTION IN EUROPE Political Controversies and Public Philosophies TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia • Rome • Tokyo TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress Copyright © 2016 by Temple University—Of Th e Commonwealth System of Higher Education All rights reserved Published 2016 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: O’Brien, Peter, 1960– author. Title: Th e Muslim question in Europe : political controversies and public philosophies / Peter O’Brien. Description: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania : Temple University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifi ers: LCCN 2015040078| ISBN 9781439912768 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781439912775 (paper : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781439912782 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Muslims—Europe—Politics and government. | Islam and politics—Europe. Classifi cation: LCC D1056.2.M87 O27 2016 | DDC 305.6/97094—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015040078 Th e paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992 Printed in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Andre, Grady, Hannah, Galen, Kaela, Jake, and Gabriel Contents Acknowledgments ix 1 Introduction: Clashes within Civilization 1 2 Kulturkampf 24 3 Citizenship 65 4 Veil 104 5 Secularism 144 6 Terrorism 199 7 Conclusion: Messy Politics 241 Aft erword 245 References 249 Index 297 Acknowledgments have accumulated many debts in the gestation of this study. Arleen Harri- son superintends an able and amiable cadre of student research assistants I without whose reliable and competent support this book would not have been possible. -

Deutscher Bundestag Beschlussempfehlung Und Bericht

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 18/1948 18. Wahlperiode 01.07.2014 Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Ausschusses für Wahlprüfung, Immunität und Geschäftsordnung (1. Ausschuss) zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Irene Mihalic, Dr. Konstantin von Notz, Luise Amtsberg, Volker Beck (Köln), Frank Tempel, Jan Korte, Ulla Jelpke, Martina Renner, Jan van Aken, Agnes Alpers, Kerstin Andreae, Annalena Baerbock, Dr. Dietmar Bartsch, Marieluise Beck (Bremen), Herbert Behrens, Karin Binder, Matthias W. Birkwald, Heidrun Bluhm, Dr. Franziska Brantner, Agnieszka Brugger, Christine Buchholz, Eva Bulling-Schröter, Roland Claus, Sevim Da÷delen,Dr.DietherDehm,EkinDeligöz,KatMaDörner,KatharinaDröge, Harald Ebner, Klaus Ernst, Dr. Thomas Gambke, Matthias Gastel, Wolfgang Gehrcke, Kai Gehring, Katrin Göring-Eckardt, Diana Golze, Annette Groth, Dr. Gregor Gysi, Heike Hänsel, Dr. André Hahn, Anja Hajduk, Britta Haßelmann, Dr. Rosemarie Hein, Inge Höger, Bärbel Höhn, Dr. Anton Hofreiter, Andrej Hunko, Sigrid Hupach, Dieter Janecek, Susanna Karawanskij, Kerstin Kassner, Uwe Kekeritz, Katja Keul, Sven-Christian Kindler, Katja Kipping, Maria Klein-Schmeink, Tom Koenigs, Sylvia Kotting-Uhl, Jutta Krellmann, Oliver Krischer, Stephan Kühn (Dresden), Christian Kühn (Tübingen), Renate Künast, Katrin Kunert, Markus Kurth, Caren Lay, Monika Lazar, Sabine Leidig, Steffi Lemke, Ralph Lenkert, Michael Leutert, Stefan Liebich, Dr. Tobias Lindner, Dr. Gesine Lötzsch, Thomas Lutze, Nicole Maisch, Peter Meiwald, Cornelia Möhring, Niema Movassat, Beate Müller-Gemmeke, Özcan Mutlu, Thomas Nord, Omid Nouripour, Cem Özdemir, Friedrich Ostendorff, Petra Pau, Lisa Paus, Harald Petzold (Havelland), Richard Pitterle, Brigitte Pothmer, Tabea Rößner, Claudia Roth (Augsburg), Corinna Rüffer, Manuel Sarrazin, Elisabeth Scharfenberg, Ulle Schauws, Dr. Gerhard Schick, Michael Schlecht, Dr. Frithjof Schmidt, Kordula Schulz-Asche, Dr. Petra Sitte, Kersten Steinke, Dr. Wolfgang Strengmann-Kuhn, Hans-Christian Ströbele, Dr. -

Geht Es Zum Brief

Ute Koczy, Tom Koenigs, Claudia Roth, Frithjof Schmidt, Ekin Deligöz, Agnieszka Malcak, Kerstin Müller, Omid Nouripour, Priska Hinz, Katja Keul, Hans-Christian Ströbele, Marieluise Beck, Thilo Hoppe, Uwe Kekeritz, Monika Lazar, Katja Dörner Mitglieder des Deutschen Bundestages Deutscher Bundestag, 11011 Berlin An den Stellvertreter der Bundeskanzlerin und Bundesminister des Auswärtigen Dr. Guido Westerwelle Auswärtiges Amt und den Bundesminister für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung Dirk Niebel BMZ – Dienstsitz Berlin Postaustausch Berlin, 04.03.2011 Sehr geehrter Herr Minister Dr. Westerwelle, sehr geehrter Herr Minister Niebel, in den letzten Wochen wurden Pläne des afghanischen Ministeriums für Frauenangelegenheiten öffentlich, alle afghanischen Frauenhäuser unter die direkte Kontrolle der Regierung zu stellen. Konservative Parlamentsmitglieder in Afghanistan haben laut Medienberichten angedeutet, die bestehenden Frauenhäuser sogar ganz schließen zu wollen. Auch wenn die afghanische Regierung angesichts des Drucks aus der Zivilgesellschaft diese Pläne nun vorerst nicht umsetzen will, ist Ihr aktives Engagement für Frauenhäuser und Frauenrechte dringend nötig. Eine Umsetzung dieser Pläne wäre ein klarer Rückschritt für die Menschen- und ganz besonders die Frauenrechte in Afghanistan. Zuflucht suchende Mädchen und Frauen müssten sich nach diesen Planungen in Zukunft äußerst zweifelhaften und der Würde des Menschen nicht gerecht werdenden physischen Untersuchungen unterwerfen, die auch einen Test auf Jungfräulichkeit einbeziehen. Ein Gremium soll dann entscheiden, ob die Frauen zugelassen, wieder nach Hause geschickt oder gar ins Gefängnis gesteckt werden. Einmal zugelassen, sollen sie die Frauenhäuser nicht mehr verlassen dürfen, was einem Aufenthalt im Gefängnis gleich käme. Frauen sollen sogar auf Verlangen der Familien, vor denen sie doch geflohen sind, an diese zurückgegeben werden. Diese Frauen sind häufig Opfer häuslicher Gewalt.