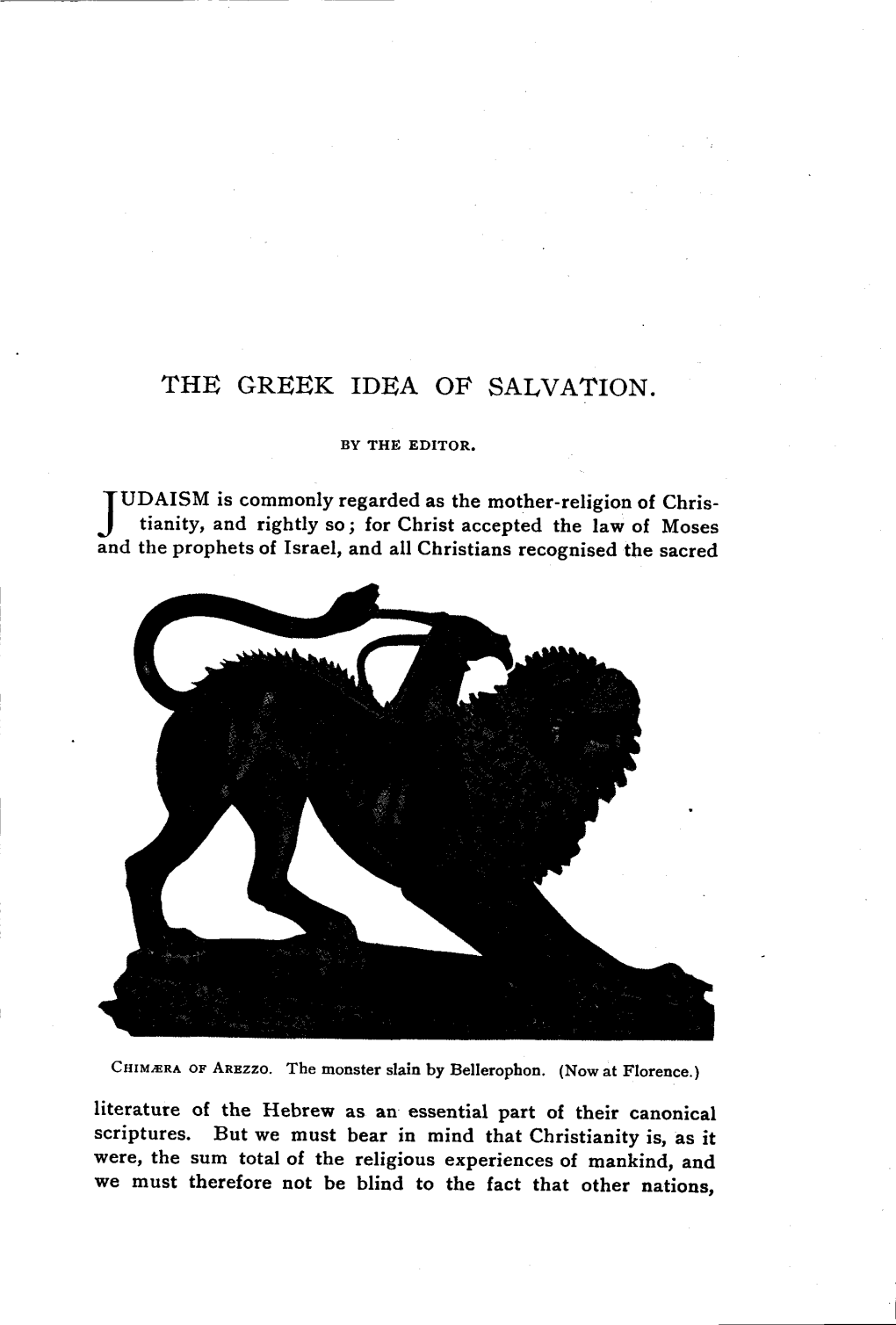

The Greek Idea of Salvation. with Numerous Illustrations from Ancient

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Heracles's Weariness and Apotheosis in Classical Greek Art

Dourado Lopes, Antonio Orlando Heracles's weariness and apotheosis in Classical Greek art Synthesis 2018, vol. 25, nro. 2, e042 Dourado Lopes, A. (2018). Heracles's weariness and apotheosis in Classical Greek art. Synthesis, 25 (2), e042. En Memoria Académica. Disponible en: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/art_revistas/pr.10707/pr.10707.pdf Información adicional en www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ ARTÍCULO / ARTICLE Synthesis, vol. 25, nº 2, e042, diciembre 2018. ISSN 1851-779X Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Centro de Estudios Helénicos Heracles's weariness and apotheosis in Classical Greek art Agotamiento físico y apoteosis de Heracles en el arte clásico griego Antonio Orlando Dourado Lopes Universidad Federal de Minas Gerais, Brasil [email protected] Resumen: Este estudio propone una interpretación general de las imágenes realizadas en Grecia, a partir del siglo V a. C. en monedas, joyas, pinturas de vasijas y esculturas, que muestran el agotamiento físico de Heracles y su apoteosis divina. Luego de una extendida consideración de los principales trabajos académicos que abordaron el tema desde finales del siglo XIX, procuro mostrar que la representación iconográfica del agotamiento de Heracles y de su apoteosis da testimonio de la influencia de nuevas concepciones religiosas y filosóficas en su mito, fundamentalmente del pitagorismo, del orfismo y de los cultos mistéricos, así como del fuerte intelectualismo de la Atenas del siglo V a. C. -

Mark of Athena Olympic Event

The Mark of Athena OLYMPIC EVENT KIT in celebration of new york times #1 best-selling series | heroesofolympus.com Greetings, Demigods! In The Heroes of Olympus, Book Three: The Mark of Athena, the Greeks and Romans are coming together, and the results are bound to be epic! As Jason, Percy, and friends unite, they soon find themselves on a quest . and the Prophecy of Seven will begin to unfold. Bring a little Greek and Roman magic to your local bookstore or library with The Mark of Athena Olympic Event Kit! Inside this kit you’ll find party ideas, reproducible activity sheets, discussion questions, and more to make for the ultimate Heroes of Olympus celebration. So prepare your lucky laurel wreath, practice your Aphrodite charmspeak, and get ready to party with The Heroes of Olympus! Have fun, | heroesofolympus.com 2 Table of Contents Throw a Demigod Fiesta .................................................4 Getting a Proper Demigod Education .............................6 Determine Your Greek or Roman Allegiance ...................7 Uncover a New God ........................................................8 Joining the Heroes of Olympus Quest .............................9 Greek and Roman God Challenge ................................. 10 Who Did What When? .................................................. 12 Giving the Girls Their Due ............................................ 14 Who Said What Now? ................................................... 16 Great Beasts of Greek Mythology ................................. 17 What Comes -

Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature Author(S): John Day Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol

Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature Author(s): John Day Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 105, No. 3 (Sep., 1986), pp. 385-408 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3260509 . Accessed: 11/05/2013 22:44 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 143.207.2.50 on Sat, 11 May 2013 22:44:00 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JBL 105/3 (1986) 385-408 ASHERAH IN THE HEBREW BIBLE AND NORTHWEST SEMITIC LITERATURE* JOHN DAY Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford University, England, OX2 6QA The late lamented Mitchell Dahood was noted for the use he made of the Ugaritic and other Northwest Semitic texts in the interpretation of the Hebrew Bible. Although many of his views are open to question, it is indisputable that the Ugaritic and other Northwest Semitic texts have revolutionized our understanding of the Bible. One matter in which this is certainly the case is the subject of this paper, Asherah.' Until the discovery of the Ugaritic texts in 1929 and subsequent years it was common for scholars to deny the very existence of the goddess Asherah, whether in or outside the Bible, and many of those who did accept her existence wrongly equated her with Astarte. -

Rick Riordan ( Is the Author of fi Ve RICK RIORDAN at Sam Houston State University

This guide was created by Dr. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Rose Brock, an assistant professor Rick Riordan (www.rickriordan.com) is the author of fi ve RICK RIORDAN at Sam Houston State University. New York Times #1 best-selling series with millions of copies sold Dr. Brock holds a PhD in library throughout the world: Percy Jackson and the Olympians, the science, specializing in children’s Kane Chronicles, the Heroes of Olympus, the Trials of Apollo, and young adult literature. and Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard. His collections of Greek myths, Percy Jackson’s Greek Gods and Percy Jackson’s Greek Many more guides can be found Heroes, were New York Times #1 best sellers as well. His novels Michael Frost Michael on the Disney • Hyperion website for adults include the hugely popular Tres Navarre series, winner at www.disneybooks.com. of the top three awards in the mystery genre. He lives in Boston, Massachusetts, with his wife and two sons. Books by Rick Riordan The Trials of Apollo BOOK ONE BOOK TWO BOOK THREE BOOK FOUR BOOK FIVE THE HIDDEN THE DARK THE BURNING THE TYRANT’S THE TOWER ORACLE PROPHECY MAZE TOMB OF NERO Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover 978-1-4847-3274-8 978-1-4847-4642-4 978-1-4847-4643-1 978-1-4847-4644-8 978-1-4847-4645-5 $19.99 $19.99 $19.99 $19.99 $19.99 Paperback Paperback Paperback Paperback Paperback 978-1-4847-4641-7 978-1-4847-8064-0 978-1-4847-8065-7 978-1-4847-8066-4 978-1-4847-8067-1 $9.99 $9.99 $9.99 $9.99 $9.99 Other Series Available This guide is aligned with the College and Career Readiness (CCR) anchor standards for Literature, Writing, Language, and Speaking and Listening. -

Land of Myth Odyssey Players

2 3 ἄνδρα µοι ἔννεπε, µοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς µάλα πολλὰ πλάγχθη, ἐπεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσεν· πολλῶν δ᾽ ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω, πολλὰ δ᾽ ὅ γ᾽ ἐν πόντῳ πάθεν ἄλγεα ὃν κατὰ θυµόν, ἀρνύµενος ἥν τε ψυχὴν καὶ νόστον ἑταίρων. Homer’s Odyssey, Book 1, Lines 1-5 (ΟΜΗΡΟΥ ΟΔΥΣΣΕΙΑ, ΡΑΨΟΔΙΑ 1, ΣΤΙΧΟΙ 1-5) CREDITS INDEX Credits – The Land of Myth™ Team Written & Designed by: John R. Haygood Art Direction: George Skodras, Ali Dogramaci Who We Are .............................................................................................. 6 Cover Art: Ali Dogramaci What is this Product ................................................................................. 6 Proofreading & Editing: Vi Huntsman (MRC) This is a product created by Seven Thebes in collaboration with the Getty Museum Introduction ................................................................................................ 7 in Los Angeles, USA. Special thanks for the many hours of game testing and brainstorming: Safety and Consent .................................................................................. 10 Thanasis Giannopoulos, Alexandros Stivaktakis, Markos Spanoudakis The Land of Myth Mechanics: A Rules-Light Version ...................... 12 First Edition First Release: November 2020 Telemachos and His Quest ................................................................... 24 Character Sheets ...................................................................................... 26 Playtest Material V0.3 Please note that this game is still -

The Apotheosis of He#Rakle#S on Olympus and the Mythological Origins of the Olympics

The apotheosis of He#rakle#s on Olympus and the mythological origins of the Olympics The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagy, Gregory. 2019.07.12. "The apotheosis of He#rakle#s on Olympus and the mythological origins of the Olympics." Classical Inquiries. http://nrs.harvard.edu/ urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries. Published Version https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/the-apotheosis-of- herakles-on-olympus-and-the-mythological-origins-of-the- olympics/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41364811 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Classical Inquiries Editors: Angelia Hanhardt and Keith Stone Consultant for Images: Jill Curry Robbins Online Consultant: Noel Spencer About Classical Inquiries (CI ) is an online, rapid-publication project of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public. While articles archived in DASH represent the original Classical Inquiries posts, CI is intended to be an evolving project, providing a platform for public dialogue between authors and readers. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries for the latest version of this article, which may include corrections, updates, or comments and author responses. Additionally, many of the studies published in CI will be incorporated into future CHS pub- lications. -

Nabu 2015-2-Mep-Dc

ISSN 0989-5671 2015 N°2 (juin) NOTES BRÈVES 25) À propos d’ARET XII 344, des déesses dgú-ša-ra-tum et de la naissance du prince éblaïte* — Le texte administratif ARET XII 344 est malheureusement assez lacuneux, mais à notre avis quand même très intéressant. Les lignes du texte préservées sont les suivantes: r. I’:1’-5’: ‹x›[...] / šeš-[...] / in ⸢u₄⸣ / ḫúl / ⸢íl⸣-['à*-ag*-da*-mu*] v. II’:1’-11’: ...] K[ALAM.]KAL[AM(?)] / NI-šè-na-⸢a⸣ / ma-lik-tum / è / é / daš-dar / ap / íl-'à- ag-da-mu / i[n] / [...] / [...] r. III’:1’-9’: ⸢'à⸣-[...] / 1 gír mar-t[u] zú-aka / 1 buru₄-mušen 1 kù-sal / daš-dar / NAM-ra-luki / 1 zara₆-túg ú-ḫáb / 1 giš-šilig₅* 2 kù-sig₁₇ maš-maš-SÙ / 1 šíta zabar / dga-mi-iš r. IV’:1’-10’: ⸢x⸣[...] / 10 lá-3 an-dù[l] igi-DUB-SÙ šu-SÙ DU-SÙ kù:babbar / 10 lá-3 gú-a-tum zabar / dgú-ša-ra-tum / 5 kù-sig₁₇ / é / en / ni-zi-mu / 2 ma-na 55 kù-sig₁₇ / sikil r. V’:1’-6’: [x-]NE-[t]um / [x K]A-dù-gíd / [m]a-lik-tum / i[n-na-s]um / dga-mi-iš / 1 dib 2 giš- DU 2 ti-gi-na 2 geštu-lá 2 ba-ga-NE-su!(ZU) r. VI’:1’-6’: [...]⸢x⸣ / [m]a-[li]k-tum / [šu-ba₄-]ti / [x ki]n siki / [x-]li / [x-b]a-LUM. Tout d’abord, on remarquera qu’au début du texte on peut lire in ⸢u₄⸣ / ḫúl / ⸢íl⸣-['à*-ag*-da*- mu*], c’est-à-dire « dans le jour de la fête (en l’honneur) d’íl-'à-ag-da-mu ». -

Between Scylla and Charybdis: Presuppositionalism, Circular Reasoning, and the Charge of Fideism

BETWEEN SCYLLA AND CHARYBDIS: PRESUPPOSITIONALISM, CIRCULAR REASONING, AND THE CHARGE OF FIDEISM Joseph E. Torres Perhaps the single most common argument against the apologetic method of Cornelius Van Til (1895-1987) is the charge of fideism. One doesn’t have to look far in the relevant literature to find Van Tillians disregarded or said to hold to a position that undermines Christian apologetics.1 Though the term “fideism” is being rehabilitated in some circles2, fideism is anti-apologetic and widely understood as a dogmatic proclamation of one’s view irrespective of rational argument. Nothing seems to demonstrate the fideism of presuppositionalism, so it is believed, as their rejection of linear reasoning. Van Tillians are said to embrace, as a fundamental rule of their approach, the fallacy of begging the question. If this is true, presuppositionalists fail to adequately “give a reason for [their] hope” in Christ (cf. 1 Pet. 3:15). Van Til is painted as an authoritarian who makes bare authority claims without appeal to the content of Christian faith.3 If argumentation is flouted then all that remains is a shouting match between competing authority claims. This brings to mind the argumentative stalemate in the “apologetic parable” of the “Shadoks” and the “Gibis” by John Warwick Montgomery in Van Til’s festschrift Jerusalem and Athens.4 The Purpose of this Article Too often in the literature Van Tillians are dismissed by the twin charges of circularity and fideism. In fact, I would dare say most objections to Van Til’s approach are rooted in these apparent boogey-men. -

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions

MISCELLANEOUS BABYLONIAN INSCRIPTIONS BY GEORGE A. BARTON PROFESSOR IN BRYN MAWR COLLEGE ttCI.f~ -VIb NEW HAVEN YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS MDCCCCXVIII COPYRIGHT 1918 BY YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS First published, August, 191 8. TO HAROLD PEIRCE GENEROUS AND EFFICIENT HELPER IN GOOD WORKS PART I SUMERIAN RELIGIOUS TEXTS INTRODUCTORY NOTE The texts in this volume have been copied from tablets in the University Museum, Philadelphia, and edited in moments snatched from many other exacting duties. They present considerable variety. No. i is an incantation copied from a foundation cylinder of the time of the dynasty of Agade. It is the oldest known religious text from Babylonia, and perhaps the oldest in the world. No. 8 contains a new account of the creation of man and the development of agriculture and city life. No. 9 is an oracle of Ishbiurra, founder of the dynasty of Nisin, and throws an interesting light upon his career. It need hardly be added that the first interpretation of any unilingual Sumerian text is necessarily, in the present state of our knowledge, largely tentative. Every one familiar with the language knows that every text presents many possi- bilities of translation and interpretation. The first interpreter cannot hope to have thought of all of these, or to have decided every delicate point in a way that will commend itself to all his colleagues. The writer is indebted to Professor Albert T. Clay, to Professor Morris Jastrow, Jr., and to Dr. Stephen Langdon for many helpful criticisms and suggestions. Their wide knowl- edge of the religious texts of Babylonia, generously placed at the writer's service, has been most helpful. -

Cultural History of the Lunar and Solar Eclipse in the Early Roman Empire

Cultural History of the Lunar and Solar Eclipse in the Early Roman Empire Richard C. Carrier The regularity and consistency of human imagination may be first displayed in the beliefs connected with eclipses. It is well known that these phenomena, to us now crucial instances of the exactness of natural laws, are, throughout the lower stages of civilization, the very embodiment of miraculous disaster.1 Fifteen hundred years have not yet passed since Greece numbered and named the stars and yet many nations today only know the heavens by their appearance, and do not yet understand why the moon fails or how it is overshadowed.2 More than fifteen hundred years separates these two remarks. Each reveals a gulf between the learned and unlearned, but for Tylor it is a contrast between today and long ago, or here and far away, while for Seneca it is a contrast between the wise and the vulgar, who live in the same time and place. For the lunar and solar eclipse is a phenomenon where the strongest and clearest divide appears between the educated Roman and the common multitude. In contrast with almost everything else in Roman experience, from earthquakes to disease, eclipses of sun and moon can be understood in their entirety, and explained with mathematical precision, without the aid of advanced technology or modern scientific methods. But to those who lacked the encouragement to employ careful observation and physical explanation, and who lacked the breadth of information available to the literate, the eclipse was the most awesome and dire event in human experience.