The Flexner Report Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 1906 Steven Schindler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Flexner Report ― 100 Years Later

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central YAlE JOuRNAl OF BiOlOGY AND MEDiCiNE 84 (2011), pp.269-276. Copyright © 2011. HiSTORiCAl PERSPECTivES iN MEDiCAl EDuCATiON The Flexner Report ― 100 Years Later Thomas P. Duffy, MD Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut The Flexner Report of 1910 transformed the nature and process of medical education in America with a resulting elimination of proprietary schools and the establishment of the bio - medical model as the gold standard of medical training. This transformation occurred in the aftermath of the report, which embraced scientific knowledge and its advancement as the defining ethos of a modern physician. Such an orientation had its origins in the enchant - ment with German medical education that was spurred by the exposure of American edu - cators and physicians at the turn of the century to the university medical schools of Europe. American medicine profited immeasurably from the scientific advances that this system al - lowed, but the hyper-rational system of German science created an imbalance in the art and science of medicine. A catching-up is under way to realign the professional commit - ment of the physician with a revision of medical education to achieve that purpose. In the middle of the 17th century, an cathedrals resonated with Willis’s delin - extraordinary group of scientists and natu - eation of the structure and function of the ral philosophers coalesced as the Oxford brain [1]. Circle and created a scientific revolution in the study and understanding of the brain THE HOPKINS CIRCLE and consciousness. -

Newsletteralumni News of the Newyork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Department of Surgery Volume 12, Number 2 Winter 2009

NEWSLETTERAlumni News of the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Department of Surgery Volume 12, Number 2 Winter 2009 Virginia Kneeland Frantz and 20th Century Surgical Pathology at Columbia University’s College of Physicians & Surgeons and the Presbyterian Hospital in the City of New York Marianne Wolff and James G. Chandler Virginia Kneeland was born on November 13, 1896 into a at the North East corner of East 70th Street and Madison Avenue. family residing in the Murray Hill district of Manhattan who also Miss Kneeland would receive her primary and secondary education owned and operated a dairy farm in Vermont.1 Her father, Yale at private schools on Manhattan’s East Side and enter Bryn Mawr Kneeland, was very successful in the grain business. Her mother, College in 1914, just 3 months after the Serbian assassination of Aus- Anna Ball Kneeland, would one day become a member of the Board tro-Hungarian, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which ignited the Great of Managers of the Presbyterian Hospital, which, at the time of her War in Europe. daughter’s birth, had been caring for the sick and injured for 24 years In November of 1896, the College of Physicians and Surgeons graduated second in their class behind Marjorie F. Murray who was (P&S) was well settled on West 59th Street, between 9th and 10th destined to become Pediatrician-in-Chief at Mary Imogene Bassett (Amsterdam) Avenues, flush with new assets and 5 years into a long- Hospital in 1928. sought affiliation with Columbia College.2 In the late 1880s, Vander- Virginia Frantz became the first woman ever to be accepted bilt family munificence had provided P&S with a new classrooms into Presbyterian Hospital’s two year surgical internship. -

Legal and Medical Education Compared: Is It Time for a Flexner Report on Legal Education?

Washington University Law Review Volume 59 Issue 3 Legal Education January 1981 Legal and Medical Education Compared: Is It Time for a Flexner Report on Legal Education? Robert M. Hardaway University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Robert M. Hardaway, Legal and Medical Education Compared: Is It Time for a Flexner Report on Legal Education?, 59 WASH. U. L. Q. 687 (1981). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol59/iss3/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEGAL AND MEDICAL EDUCATION COMPARED: IS IT TIME FOR A FLEXNER REPORT ON LEGAL EDUCATION? ROBERT M. HARDAWAY* I. INTRODUCTION In 1907, medical education in the United States was faced with many of the problems' that critics feel are confronting legal education today:3 an over-production of practitioners, 2 high student-faculty ratios, proliferation of professional schools, insufficient financing,4 and inade- * Assistant Professor, University of Denver College of Law. B.A., 1966, Amherst College; J.D., 1971, New York University. The author wishes to acknowledge gratefully the assistance of Heather Stengel, a third year student at the University of Denver College of Law, in the prepara- tion of this article and the tabulation of statistical data. -

Medical School Expansion in the 21St Century Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine

Medical School Expansion in the 21st Century Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine Michael E. Whitcomb, M.D. and Douglas L. Wood, D.O., Ph.D. September 2015 Cover: University of New England campus Medical School Expansion in the 21st Century Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine Michael E. Whitcomb, M.D. and Douglas L. Wood, D.O., Ph.D. FOREWORD The Macy Foundation has recently documented the motivating factors, major challenges, and planning strategies for the fifteen new allopathic medical schools (leading to the M.D. degree) that enrolled their charter classes between 2009 and 2014.1,2 A parallel trend in the opening of new osteopathic medical schools (leading to the D.O. degree) began in 2003. This expansion will result in a greater proportional increase in the D.O. workforce than will occur in the M.D. workforce as a result of the allopathic expansion. With eleven new osteopathic schools and nine new sites or branches for existing osteopathic schools, there will be more than a doubling of the D.O. graduates in the U.S. by the end of this decade. Douglas Wood, D.O., Ph.D., and Michael Whitcomb, M.D., bring their broad experiences in D.O. and M.D. education to this report of the osteopathic school expansion. They identify ways in which the new schools are similar to and different from the existing osteopathic schools, and they identify differences in the rationale and characteristics of the new osteopathic schools, compared with those of the new allopathic schools that Dr. Whitcomb has previously chronicled. 1 Whitcomb ME. -

US Medical Education Reformers Abraham Flexner (1866-1959) and Simon Flexner (1863-1946)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 443 765 SO 031 860 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty J. TITLE U.S. Medical Education Reformers Abraham Flexner (1866-1959) and Simon Flexner (1863-1946). PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 12p. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biographies; *Educational Change; *Educational History; Higher Education; *Medical Education; *Professional Recognition; *Social History IDENTIFIERS *Flexner (Abraham); Johns Hopkins University MD; Reform Efforts ABSTRACT This paper (in the form of a dialogue) tells the stories of two members of a remarkable family of nine children, the Flexners of Louisville, Kentucky. The paper focuses on Abraham and Simon, who were reformers in the field of medical education in the United States. The dialogue takes Abraham Flexner through his undergraduate education at Johns Hopkins University, his founding of a school that specialized in educating wealthy (but underachieving) boys, and his marriage to Anne Laziere Crawford. Abraham and his colleague, Henry S. Pritchett, traveled around the country assessing 155 medical schools in hopes of professionalizing medical education. The travels culminated in a report on "Medical Education in the United States and Canada" (1910). Abraham capped his career by creating the first significant "think tank," the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. The paper also profiles Simon Flexner, a pharmacist whose dream was to become a pathologist. Simon, too, gravitated to Johns Hopkins University where he became chief pathologist and wrote over 200 pathology and bacteriology reports between 1890-1909. He also helped organize the Peking Union Medical College in Peking, China, and was appointed Eastman Professor at Oxford University.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

The Flexner Report: 100 Years Later

International Journal of Medical Education. 2010; 1:74-75 Letter ISSN: 2042-6372 DOI: 10.5116/ijme.4cb4.85c8 The Flexner report: 100 years later Douglas Page, Adrian Baranchuk Department of Cardiology, Kingston General Hospital, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada Correspondence: Adrian Baranchuk, Department of Cardiology, Kingston General Hospital, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada, Email: [email protected] Accepted: October 12, 2010 One hundred years ago, medical education in the US and Following Flexner’s recommendations, accreditation Canada was very different than it is today. There was little programs and a shift in resources led to the closure of standardization regulating how medical education was many of the medical schools in existence at that time. delivered, and there was wide variation in the aptitude of Medical training became much more centralized, with practicing physicians. Though some medical education was smaller rural schools closing down as resources were delivered by the universities, many non-university affiliated concentrated in larger Universities that had better training schools still existed. Besides scientific medicine, homeo- facilities. Proprietary schools were terminated, and medi- pathic, osteopathic, chiropractic, botanical, eclectic, and cal education was delivered with the philosophy that basic physiomedical medicine were all taught and practiced by sciences and clinical experience were paramount to pro- different medical doctors at that time. In addition, there ducing effective physicians.2 -

Abraham Flexner As Critic of British and Continental Medical Education

Medical History, 1989, 33: 472-479. ABRAHAM FLEXNER AS CRITIC OF BRITISH AND CONTINENTAL MEDICAL EDUCATION by THOMAS NEVILLE BONNER * When Abraham Flexner landed in England in October 1910, he was already well known in British medical circles. His report on medical education in the United States and Canada, published earlier in the year, had been widely distributed in Europe by Nicholas Murray Butler, an influential trustee of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. When Flexner called on the president of the Royal College of Surgeons, Henry Butlin, on 8 October, Butlin told him of the impact his American study had made in Britain. "You didn't need any letter of introduction from Osler," Flexner recounted the conversation, "I've read your report, it's masterly. I am preparing a memorial to the Royal Commission on London University and you are my authority-see here, here's your Report ... every margin filled with pencil comments showing how you have analyzed our difficulties for us . Flexner's arrival in Britain was timely. Medical education throughout the island was in turmoil. Dissatisfaction with the variety of routes to licensure, the wide differences between Scottish and London requirements for degrees, and the rigidity of the seniority system within the hospitals had been growing since the 1880s. In addition, new concerns over British backwardness in laboratory study and scientific research were creating a sense of crisis in those aware of developments in Germany and America.2 William Osler himself, who had arrived at Oxford to fill the Regius Chair in 1905, had sharply criticized a year earlier the neglect of laboratory studies in British medical schools in a widely reported address at the London Hospital.3 Flexner conferred with Osler and other members of the British medical establishment on his arrival in Britain. -

Abraham Flexner and His Views on Learning in Higher Education

Iwabuchi Sachiko(p139)6/2 04.9.6 3:13 PM ページ 139 The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 15 (2004) The Pursuit of Excellence: Abraham Flexner and His Views on Learning in Higher Education Sachiko IWABUCHI* INTRODUCTION Abraham Flexner, one of the most influential educational critics in early twentieth-century America, faithfully believed in excellence. Ex- cellence epitomized his views on education. “Throughout my life,” Flexner wrote in his autobiography, “I have pursued excellence.”1 For Flexner, excellence meant more than surpassing skills, eminence, and dignity; excellence meant intellectual rather than mere mental training. It also connoted honor and spirituality rather than mercantilism and materialism. For Flexner an aristocracy of excellence is “the truest form of democracy.”2 The topic of excellence has become conspicuous in the discussions of university reform in Japan. The Twenty-First Century Centers of Ex- cellence (COE) Program was established based on the Ministry of Edu- cation, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology’s report “A Policy for the Structural Reform of National Universities,” under which a new funding mechanism has been implemented to subsidize the formation of research bases.3 Although the goal of the COEs is to promote excellent research results, some scholars have argued that the proposed program could drive researchers to commercially successful projects in order to Copyright © 2004 Sachiko Iwabuchi. All rights reserved. This work may be used, with this notice included, for noncommercial purposes. No copies of this work may be distrib- uted, electronically or otherwise, in whole or in part, without permission from the author. *Ph. D. -

A Brief Guide to Osteopathic Medicine for Students, by Students

A Brief Guide to Osteopathic Medicine For Students, By Students By Patrick Wu, DO, MPH and Jonathan Siu, DO ® Second Edition Updated April 2015 Copyright © 2015 ® No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine 5550 Friendship Boulevard, Suite 310 Chevy Chase, MD 20815-7231 Visit us on Facebook Please send any comments, questions, or errata to [email protected]. Cover Photos: Surgeons © astoria/fotolia; Students courtesy of A.T. Still University Back to Table of Contents Table of Contents Contents Dedication and Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................ ii Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Myth or Fact?....................................................................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER 1: What is a DO? .............................................................................................................................. -

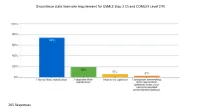

Discontinue State Licensure Requirement for USMLE Step 2 CS and COMLEX Level 2 PE

Discontinue state licensure requirement for USMLE Step 2 CS and COMLEX Level 2 PE 205 Responses Please indicate your view of this resolution as an ISMS priority. 202 Responses Survey Title: Resolution Survey Report Type: Verbatim Comments SR No. Response No. Response Text 1 5 Agree 2 7 Consider continued requirement for IMGs to complete USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills for licensure in Illinois. 3 11 This is an undue burden on US medical students. 4 12 We need some standards for the graduating and new doctors! 5 15 Cost savings for new grads. no loss of competency 6 18 so what happens to the graduates of schools outside the US? so they still take the exam. are we setting up differential qualifications for licensure by stating that this test is not required of US graduates of allopathic and osteopathic schools? 7 83 Need to know the pros and c 8 27 I agree 9 35 The best reflection as to how a student is test results. I am concerned you would lose all ways to judge. 10 38 Strongly support. We pay so much for medical school and are subsequently nickeled and dimed for USMLE exams as well. There are many issues at stake here but do not overlook the financial burden of CS. 11 40 If this issue has been studied by the AMA and if they have come to the conclusion after study that these exams should be stopped, then I agree with the resolution. 12 45 Make perfect sense, making one wonder why such a modification wasn't enacted a generation or two ago. -

Pay to Play: the Future of Clinical Clerkships?

Pay to Play: The Future of Clinical Clerkships? Mary Ann Forciea MD Clinical Professor of Medicine May 25, 2016 Brief History of Medical Education in the United States • 19th Century Models of Medical Training: – Apprenticeship: students worked with a practicing physician – Proprietary schools: students attended courses given by physicians who owned the college – University : clinical and didactic training at a University affiliated school In what year did African American medical students have the LEAST ACCESS TO TRAINING? • A 1895 • B 1925 • C 2000 19th Century Models • Problems: – No admission standards – No length of training standards • No equipment or laboratory standards – No curricular standards – No financing uniformity • Benefits – Diverse training possibilities – Wide ranging content available Meanwhile, at the University of Pennsylvania….. • Who was the first Dean of the College of Medicine? – Benjamin Rush – Benjamin Franklin – John Morgan – Ichabod Wright The School of Medicine created a Paradigm Shift (in the 1870s) by: • Paying faculty to teach courses • Integrating community service into the curriculum • Building its own teaching hospital • Accepting women Medical Education at University of Pennsylvania • Medical School created at the ‘College of Pennsylvania’ in 1765 – Creating the ‘University of Pennsylvania” • John Morgan the first Dean • Medical faculty distinct from College Faculty – Clinical work at Pennsylvania Hospital (1751) • West Philadelphia campus move 1870s – HUP the first teaching hospital built FOR the -

Allopathic and Osteopathic Medicine Unify GME Accreditation: a Historic Convergence Abdul-Kareem H

SPECIAL ARTICLES Allopathic and Osteopathic Medicine Unify GME Accreditation: A Historic Convergence Abdul-Kareem H. Ahmed, SM; Peter F. Schnatz, DO, NCMP; Eli Y. Adashi, MD, MS BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: In 1968, the American Medical As- this latest development redefines sociation resolved to accept qualified graduates of osteopathic medical the allopathic-osteopathic interface schools into its accredited Graduate Medical Education (GME) programs. in a manner reminiscent of the his- An equally momentous decision was arrived at in 2014 when the Accredi- toric 1968 decision of the American tation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the American Os- Medical Association (AMA) to accept teopathic Association (AOA), and the American Association of Colleges of qualified graduates of osteopathic Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM) resolved to institute a single unified GME medical schools into AMA-accredit- accreditation system by July 1, 2020. As envisioned, the unified accredi- ed GME programs.3 tation system will all but assure system-wide consistency of purpose and practice in anticipation of the Next Accreditation System (NAS) of the AC- Osteopathic Medicine GME. Governance integration replete with AOA and AACOM and osteopath- and the ACGME ic representation on the ACGME Board of Directors is now well underway. Central to this transition is the des- What is more, osteopathic representation on current Review Committees (RCs) and in a newly established one with an osteopathic focus has been ignation of the AOA and AACOM instituted. Viewed broadly, the unification of the GME accreditation system as member organizations of the goes a long way toward recognizing the overlapping characteristics in the ACGME and their representation training and practice of allopathic and osteopathic medicine.