The Medical Education of Physicians P a P E R NO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Flexner Report ― 100 Years Later

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central YAlE JOuRNAl OF BiOlOGY AND MEDiCiNE 84 (2011), pp.269-276. Copyright © 2011. HiSTORiCAl PERSPECTivES iN MEDiCAl EDuCATiON The Flexner Report ― 100 Years Later Thomas P. Duffy, MD Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut The Flexner Report of 1910 transformed the nature and process of medical education in America with a resulting elimination of proprietary schools and the establishment of the bio - medical model as the gold standard of medical training. This transformation occurred in the aftermath of the report, which embraced scientific knowledge and its advancement as the defining ethos of a modern physician. Such an orientation had its origins in the enchant - ment with German medical education that was spurred by the exposure of American edu - cators and physicians at the turn of the century to the university medical schools of Europe. American medicine profited immeasurably from the scientific advances that this system al - lowed, but the hyper-rational system of German science created an imbalance in the art and science of medicine. A catching-up is under way to realign the professional commit - ment of the physician with a revision of medical education to achieve that purpose. In the middle of the 17th century, an cathedrals resonated with Willis’s delin - extraordinary group of scientists and natu - eation of the structure and function of the ral philosophers coalesced as the Oxford brain [1]. Circle and created a scientific revolution in the study and understanding of the brain THE HOPKINS CIRCLE and consciousness. -

Legal and Medical Education Compared: Is It Time for a Flexner Report on Legal Education?

Washington University Law Review Volume 59 Issue 3 Legal Education January 1981 Legal and Medical Education Compared: Is It Time for a Flexner Report on Legal Education? Robert M. Hardaway University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Robert M. Hardaway, Legal and Medical Education Compared: Is It Time for a Flexner Report on Legal Education?, 59 WASH. U. L. Q. 687 (1981). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol59/iss3/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEGAL AND MEDICAL EDUCATION COMPARED: IS IT TIME FOR A FLEXNER REPORT ON LEGAL EDUCATION? ROBERT M. HARDAWAY* I. INTRODUCTION In 1907, medical education in the United States was faced with many of the problems' that critics feel are confronting legal education today:3 an over-production of practitioners, 2 high student-faculty ratios, proliferation of professional schools, insufficient financing,4 and inade- * Assistant Professor, University of Denver College of Law. B.A., 1966, Amherst College; J.D., 1971, New York University. The author wishes to acknowledge gratefully the assistance of Heather Stengel, a third year student at the University of Denver College of Law, in the prepara- tion of this article and the tabulation of statistical data. -

The Flexner Report: 100 Years Later

International Journal of Medical Education. 2010; 1:74-75 Letter ISSN: 2042-6372 DOI: 10.5116/ijme.4cb4.85c8 The Flexner report: 100 years later Douglas Page, Adrian Baranchuk Department of Cardiology, Kingston General Hospital, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada Correspondence: Adrian Baranchuk, Department of Cardiology, Kingston General Hospital, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada, Email: [email protected] Accepted: October 12, 2010 One hundred years ago, medical education in the US and Following Flexner’s recommendations, accreditation Canada was very different than it is today. There was little programs and a shift in resources led to the closure of standardization regulating how medical education was many of the medical schools in existence at that time. delivered, and there was wide variation in the aptitude of Medical training became much more centralized, with practicing physicians. Though some medical education was smaller rural schools closing down as resources were delivered by the universities, many non-university affiliated concentrated in larger Universities that had better training schools still existed. Besides scientific medicine, homeo- facilities. Proprietary schools were terminated, and medi- pathic, osteopathic, chiropractic, botanical, eclectic, and cal education was delivered with the philosophy that basic physiomedical medicine were all taught and practiced by sciences and clinical experience were paramount to pro- different medical doctors at that time. In addition, there ducing effective physicians.2 -

A Brief Guide to Osteopathic Medicine for Students, by Students

A Brief Guide to Osteopathic Medicine For Students, By Students By Patrick Wu, DO, MPH and Jonathan Siu, DO ® Second Edition Updated April 2015 Copyright © 2015 ® No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine 5550 Friendship Boulevard, Suite 310 Chevy Chase, MD 20815-7231 Visit us on Facebook Please send any comments, questions, or errata to [email protected]. Cover Photos: Surgeons © astoria/fotolia; Students courtesy of A.T. Still University Back to Table of Contents Table of Contents Contents Dedication and Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................ ii Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Myth or Fact?....................................................................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER 1: What is a DO? .............................................................................................................................. -

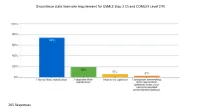

Discontinue State Licensure Requirement for USMLE Step 2 CS and COMLEX Level 2 PE

Discontinue state licensure requirement for USMLE Step 2 CS and COMLEX Level 2 PE 205 Responses Please indicate your view of this resolution as an ISMS priority. 202 Responses Survey Title: Resolution Survey Report Type: Verbatim Comments SR No. Response No. Response Text 1 5 Agree 2 7 Consider continued requirement for IMGs to complete USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills for licensure in Illinois. 3 11 This is an undue burden on US medical students. 4 12 We need some standards for the graduating and new doctors! 5 15 Cost savings for new grads. no loss of competency 6 18 so what happens to the graduates of schools outside the US? so they still take the exam. are we setting up differential qualifications for licensure by stating that this test is not required of US graduates of allopathic and osteopathic schools? 7 83 Need to know the pros and c 8 27 I agree 9 35 The best reflection as to how a student is test results. I am concerned you would lose all ways to judge. 10 38 Strongly support. We pay so much for medical school and are subsequently nickeled and dimed for USMLE exams as well. There are many issues at stake here but do not overlook the financial burden of CS. 11 40 If this issue has been studied by the AMA and if they have come to the conclusion after study that these exams should be stopped, then I agree with the resolution. 12 45 Make perfect sense, making one wonder why such a modification wasn't enacted a generation or two ago. -

Pay to Play: the Future of Clinical Clerkships?

Pay to Play: The Future of Clinical Clerkships? Mary Ann Forciea MD Clinical Professor of Medicine May 25, 2016 Brief History of Medical Education in the United States • 19th Century Models of Medical Training: – Apprenticeship: students worked with a practicing physician – Proprietary schools: students attended courses given by physicians who owned the college – University : clinical and didactic training at a University affiliated school In what year did African American medical students have the LEAST ACCESS TO TRAINING? • A 1895 • B 1925 • C 2000 19th Century Models • Problems: – No admission standards – No length of training standards • No equipment or laboratory standards – No curricular standards – No financing uniformity • Benefits – Diverse training possibilities – Wide ranging content available Meanwhile, at the University of Pennsylvania….. • Who was the first Dean of the College of Medicine? – Benjamin Rush – Benjamin Franklin – John Morgan – Ichabod Wright The School of Medicine created a Paradigm Shift (in the 1870s) by: • Paying faculty to teach courses • Integrating community service into the curriculum • Building its own teaching hospital • Accepting women Medical Education at University of Pennsylvania • Medical School created at the ‘College of Pennsylvania’ in 1765 – Creating the ‘University of Pennsylvania” • John Morgan the first Dean • Medical faculty distinct from College Faculty – Clinical work at Pennsylvania Hospital (1751) • West Philadelphia campus move 1870s – HUP the first teaching hospital built FOR the -

Allopathic and Osteopathic Medicine Unify GME Accreditation: a Historic Convergence Abdul-Kareem H

SPECIAL ARTICLES Allopathic and Osteopathic Medicine Unify GME Accreditation: A Historic Convergence Abdul-Kareem H. Ahmed, SM; Peter F. Schnatz, DO, NCMP; Eli Y. Adashi, MD, MS BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: In 1968, the American Medical As- this latest development redefines sociation resolved to accept qualified graduates of osteopathic medical the allopathic-osteopathic interface schools into its accredited Graduate Medical Education (GME) programs. in a manner reminiscent of the his- An equally momentous decision was arrived at in 2014 when the Accredi- toric 1968 decision of the American tation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the American Os- Medical Association (AMA) to accept teopathic Association (AOA), and the American Association of Colleges of qualified graduates of osteopathic Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM) resolved to institute a single unified GME medical schools into AMA-accredit- accreditation system by July 1, 2020. As envisioned, the unified accredi- ed GME programs.3 tation system will all but assure system-wide consistency of purpose and practice in anticipation of the Next Accreditation System (NAS) of the AC- Osteopathic Medicine GME. Governance integration replete with AOA and AACOM and osteopath- and the ACGME ic representation on the ACGME Board of Directors is now well underway. Central to this transition is the des- What is more, osteopathic representation on current Review Committees (RCs) and in a newly established one with an osteopathic focus has been ignation of the AOA and AACOM instituted. Viewed broadly, the unification of the GME accreditation system as member organizations of the goes a long way toward recognizing the overlapping characteristics in the ACGME and their representation training and practice of allopathic and osteopathic medicine. -

The A.M.A. and the Supply of Physicians* Rben A

THE A.M.A. AND THE SUPPLY OF PHYSICIANS* RBEN A. Kssmi INTRODUCTION This paper deals with two related topics: first, the role of the American Medical Association (AMA) in determining the rate of output of physicians and, as a con- sequence, the current stock of physicians, and, second, the role of organized medicine -that is, the AMA-in circumscribing the choice of contractual relationships be- tween physicians and their patients. Because it is my thesis that the famous Flexner report of igio constituted the key to achieving control over the output of physicians by the AMA, a substantial portion of this paper is devoted to this report and its implications for understanding how our society produces physicians. The history of public intervention in the market for medical services can be con- veniently divided into two periods. The earlier begins with the publication of the Flexner report and ends with the conclusion of World War II. During this period, public intervention in the market for medical services had its principal effect on the supply of physicians' services. Organized medicine-again, the AMA-, using powers delegated by state governments, reduced the output of doctors by making the grad- uates of some medical schools ineligible to be examined for licensure and by reducing the output of schools that continued to produce eligible graduates. This led to the demise of the schools producing ineligible graduates, since training doctors was their raison d'tre. For the surviving schools, their costs of producing doctors increased enormously. The later period, which begins with the end of World War II and continues to the present moment, may be characterized as a period when governmental inter- vention, through programs such as Kerr-Mills, Medicaid, and Medicare, operated to increase the demand for the services of doctors. -

What Is a Clinical Clerkship?

1 www.acofp.org WHAT IS A CLINICAL CLERKSHIP? Tyler Cymet, DO Chief of Clinical Education | AACOM INTRODUCTION DIFFERENTIATING CLINICAL CLERKSHIPS The field of basic science in medical education for both osteopathic On the most basic level, clinical clerkships are divided up into and allopathic follows the conventional model of classroom teach- “core” rotations and elective rotations. The core rotations required ing paired with laboratory experiences. Clinical sciences are taught at most American medical schools include family medicine and in- in practice-based settings such as hospitals, physician offices, am- ternal medicine (both medical, clinical sciences); gynecology/ob- bulatory care centers, surgical centers, and health departments stetrics and pediatrics (both general clinical sciences); and surgery with supervised hands-on experiences. Formal educational expe- (clinical suregery sciences).2 Students begin their core rotations riences are necessary as the foundation of clinical medicine, but during their 3rd year. As they complete the core rotations, they are the goal is to consolidate clinical skills and complement classroom expected to “find what they love” and tailor their elective rotations learning in a structured physician-patient environment.1 The value to their future career during their 4th year.3 of a clinical clerkship is in the application of direct care with patient reaction based on learned information. This hands-on experience gives students a unique opportunity to bridge the academic and ACADEMIC CREDIT & practice-based worlds to gain the skills necessary for health care THE CLINICAL CLERKSHIP providers. Academic credit is usually determined by “credit hours.” The Carn- egie Unit is the standard measure and is figured as 800 minutes of WHAT IS A BASIC AND CLINICAL SCIENCE? direct interaction per credit hour. -

Promoting a More Adaptable Physician Pipeline

Promoting a More Adaptable Physician Pipeline FDA & Health James C. Capretta The views expressed are those of the author in his personal capacity and not in her official/professional capacity. To cite this paper: James C. Capretta, “Promoting a More Adaptable Physician Pipeline”, released by the Regulatory Transparency Project of the Federalist Society, February 26, 2020 (https://regproject.org/wp- content/uploads/RTP-FDA-Health-Working-Group-Paper-Physician-Supply.pdf). This paper adapted from a report originally published by the American Enterprise Institute under the title “Policies affecting the number of physicians in the US and a framework for reform” (https://www.aei.org/wp- content/uploads/2020/03/Report-Policies-affecting-the-number-of-physicians-in-the-US-and-a-framework-for- reform.pdf) March 25, 2020 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 3-4 A Top-line Perspective 4-6 Historical Context 6-7 Basic Framework for Physician Licensure in the US 7-9 Foreign-Born Physicians and International Medical Graduates 9-12 Public Subsidies and Policies for Graduate Medical Education 12-15 More GME Funding Is Not the Answer 15-16 The Role of the Medicare Fee Schedule 17-18 Toward a More Flexible and Adaptable Pipeline of Prospective Physicians 18-20 Conclusion 21 2 Executive Summary Since the latter half of the 19th century, the medical profession has been effectively regulating itself through state medical boards and control of the organizations that certify educational and training institutions. The federal government participates in (but does not directly control) residency programs through partial funding provided mainly by Medicare. -

J21 Report of Reference Committee C

DISCLAIMER The following is a preliminary report of actions taken by the House of Delegates at its June 2021 Special Meeting and should not be considered final. Only the Official Proceedings of the House of Delegates reflect official policy of the Association. AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION HOUSE OF DELEGATES (J-21 Special Meeting) Report of Reference Committee [C] Tracey L. Henry, MD, MPH, Chair 1 Your Reference Committee recommends the following consent calendar for acceptance: 2 3 RECOMMENDED FOR ADOPTION 4 5 1. Council on Medical Education Report 1 – Council on Medical Education Sunset 6 Review of 2011 House Policies 7 2. Council on Medical Education Report 3 – Optimizing Match Outcomes 8 (Resolution 304-I-19) 9 3. Council on Medical Education Report 4 – Study Expediting Entry of Qualified 10 IMG Physicians to US Medical Practice 11 12 RECOMMENDED FOR ADOPTION AS AMENDED 13 14 4. Council on Medical Education Report 2 – Licensure for International Medical 15 Graduates Practicing in U.S. Institutions with Restricted Medical Licenses 16 (Resolution 311-A-19) 17 5. Council on Medical Education Report 5 – Promising Practices Among Pathway 18 Programs to Increase Diversity in Medicine 19 6. Resolution 305 – Non-Physician Post-Graduate Medical Training 20 7. Resolution 309 – Supporting GME Program Child Care Consideration During 21 Residency Training 22 8. Resolution 310 – Unreasonable Fees Charged and Inaccuracies by the American 23 Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) 24 9. Resolution 318 – The Impact of Private Equity on Medical Training 25 10. Resolution 319 – The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Graduate Medical 26 Education 27 28 RECOMMENDED FOR REFERRAL 29 30 11. -

NSU-COM Medical Education Digest

Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine Volume 12, Number 5 Published six times per year by NSU College of Osteopathic Medicine September/October 2010 An Overview of Medical Education and Geriatric Precepting in Family Medicine A University of Virginia and social talk. There were 26 family medicine residents and s t u d y i n i t s f a m i l y 12 physician faculty members in the study, including one medicine clinic attempted with a Certificate of Added Qualification in Geriatrics. to gain an understanding Of 259 patients, 33 involved people over 64 years of age. of how geriatric content The percent of older patients seen by these residents was was incorporated into less than the 20 percent typically seen in family practice. resident/attendings The data collected indicated that additional sites may be precepting encounters needed to supplement the exposure to older patients that in its family medicine residents receive in a continuity clinic. Such sites include a residency program. All combination of nursing homes, home care, and ambulatory residents and physician care precepted by a geriatrician. Family physicians, it was attendings were involved concluded, also need to possess competence and strategies in the four-week study. in addressing geriatric issues. The family medicine clinic While geriatric issues can be addressed in busy family averaged 1,900 outpatient medicine training programs by preceptors without geriatric visits monthly. certification, there should be training programs to ensure Observation of the they are able to teach residents about common geriatric encounters was by a issues encountered in outpatient settings.