Meth Mania: a History of Methamphetamine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stimulants and Hallucinogens Under Consideration: a Brief Overview of Their Chemistry and Pharmacology

Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 17 (1986) 107-118 107 Elsevier Scientific Publishers Ireland Ltd. THE STIMULANTS AND HALLUCINOGENS UNDER CONSIDERATION: A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THEIR CHEMISTRY AND PHARMACOLOGY LOUIS S. HARRIS Dcparlmcnl of Pharmacology, Medical College of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth Unwersity, Richmond, VA 23298 (U.S.A.) SUMMARY The substances under review are a heterogenous set of compounds from a pharmacological point of view, though many have a common phenylethyl- amine structure. Variations in structure lead to marked changes in potency and characteristic action. The introductory material presented here is meant to provide a set of chemical and pharmacological highlights of the 28 substances under con- sideration. The most commonly used names or INN names, Chemical Abstract (CA) names and numbers, and elemental formulae are provided in the accompanying figures. This provides both some basic information on the substances and a starting point for the more detailed information that follows in the individual papers by contributors to the symposium. Key words: Stimulants, their chemistry and pharmacology - Hallucinogens, their chemistry and pharmacology INTRODUCTION Cathine (Fig. 1) is one of the active principles of khat (Catha edulis). The structure has two asymmetric centers and exists as two geometric isomers, each of which has been resolved into its optical isomers. In the plant it exists as d-nor-pseudoephedrine. It is a typical sympathomimetic amine with a strong component of amphetamine-like activity. The racemic mixture is known generically in this country and others as phenylpropanolamine (dl- norephedrine). It is widely available as an over-the-counter (OTC) anti- appetite agent and nasal decongestant. -

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20130289061A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0289061 A1 Bhide et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 31, 2013 (54) METHODS AND COMPOSITIONS TO Publication Classi?cation PREVENT ADDICTION (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: The General Hospital Corporation, A61K 31/485 (2006-01) Boston’ MA (Us) A61K 31/4458 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. (72) Inventors: Pradeep G. Bhide; Peabody, MA (US); CPC """"" " A61K31/485 (201301); ‘4161223011? Jmm‘“ Zhu’ Ansm’ MA. (Us); USPC ......... .. 514/282; 514/317; 514/654; 514/618; Thomas J. Spencer; Carhsle; MA (US); 514/279 Joseph Biederman; Brookline; MA (Us) (57) ABSTRACT Disclosed herein is a method of reducing or preventing the development of aversion to a CNS stimulant in a subject (21) App1_ NO_; 13/924,815 comprising; administering a therapeutic amount of the neu rological stimulant and administering an antagonist of the kappa opioid receptor; to thereby reduce or prevent the devel - . opment of aversion to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Also (22) Flled' Jun‘ 24’ 2013 disclosed is a method of reducing or preventing the develop ment of addiction to a CNS stimulant in a subj ect; comprising; _ _ administering the CNS stimulant and administering a mu Related U‘s‘ Apphcatlon Data opioid receptor antagonist to thereby reduce or prevent the (63) Continuation of application NO 13/389,959, ?led on development of addiction to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Apt 27’ 2012’ ?led as application NO_ PCT/US2010/ Also disclosed are pharmaceutical compositions comprising 045486 on Aug' 13 2010' a central nervous system stimulant and an opioid receptor ’ antagonist. -

‗DEFINED NOT by TIME, but by MOOD': FIRST-PERSON NARRATIVES of BIPOLAR DISORDER by CHRISTINE ANDREA MUERI Submitted in Parti

‗DEFINED NOT BY TIME, BUT BY MOOD‘: FIRST-PERSON NARRATIVES OF BIPOLAR DISORDER by CHRISTINE ANDREA MUERI Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Kimberly Emmons Department of English CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August 2011 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Christine Andrea Mueri candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree *. (signed) Kimberly K. Emmons (chair of the committee) Kurt Koenigsberger Todd Oakley Jonathan Sadowsky May 20, 2011 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 3 I dedicate this dissertation to Isabelle, Genevieve, and Little Man for their encouragement, unconditional love, and constant companionship, without which none of this would have been achieved. To Angie, Levi, and my parents: some small piece of this belongs to you as well. 4 Table of Contents Dedication 3 List of tables 5 List of figures 6 Acknowledgements 7 Abstract 8 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: The Bipolar Story 28 Chapter 3: The Lay of the Bipolar Land 64 Chapter 4: Containing the Chaos 103 Chapter 5: Incorporating Order 136 Chapter 6: Conclusion 173 Appendix 1 191 Works Cited 194 5 List of Tables 1. Diagnostic Criteria for Manic and Depressive Episodes 28 2. Therapeutic Approaches for Treating Bipolar Disorder 30 3. List of chapters from table of contents 134 6 List of Figures 1. Bipolar narratives published by year, 2000-2010 20 2. Graph from Gene Leboy, Bipolar Expeditions 132 7 Acknowledgements I gratefully acknowledge my advisor, Kimberly Emmons, for her ongoing guidance and infinite patience. -

Toxicology Times

TOXICOLOGY (800) 677-7995 TIMES www.sdrl.com A FREE Monthly Newsletter for Substance Abuse and Opioid Treatment Volume 5, Issue 7 Programs from San Diego Reference Laboratory July, 2015 Amphetamines (Part 1) Dr. Joseph E. Graas, Scientific Director most often used in inhalers and does not tite, increased stamina and physical energy, Dr. Edward Moore, Medical Director have the central nervous system activity nor increased sexual response/drive, involuntary any addictive properties. All of the com- body movements, increased perspiration, The term “amphetamines” has come to mean pounds that have the structure of hyperactivity, nausea and increased heart rate. a class of endogenous neurotransmitters that phenylethylamine will have this mixture of d This drug is highly addictive and tolerance stimulate the sympathetic nervous system. and l molecules. In the production of these develops quickly. Withdrawal is an extremely This is a broad class of various substituted drugs they are usually noted as a racemic unpleasant experience. A few street names derivatives of phenylethylamine. This grow- mixture, or specifically, as the d or l com- for the drug are amp, speed, crank, dolls and ing class of structurally related molecules may pound. To properly evaluate this family of crystal. also stimulate the sympathetic nervous sys- compounds known as sympathomimetic tem in many different ways, such as affecting amines, amphetamines or phenylethylamine, Methamphetamine was developed by the the re-release of neurotransmitters or pre- it is best done by describing each member of Japanese in 1919 and used during World War venting the re-uptake of neurotransmitters, the class: amphetamine , methampheta- II to help soldiers stay alert and energize hallucinogens, anorectics, bronchodilators mine , phentermine , phenylpropanola- factory workers. -

Pharmacology and Toxicology of Amphetamine and Related Designer Drugs

Pharmacology and Toxicology of Amphetamine and Related Designer Drugs U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES • Public Health Service • Alcohol Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration Pharmacology and Toxicology of Amphetamine and Related Designer Drugs Editors: Khursheed Asghar, Ph.D. Division of Preclinical Research National Institute on Drug Abuse Errol De Souza, Ph.D. Addiction Research Center National Institute on Drug Abuse NIDA Research Monograph 94 1989 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration National Institute on Drug Abuse 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, DC 20402 Pharmacology and Toxicology of Amphetamine and Related Designer Drugs ACKNOWLEDGMENT This monograph is based upon papers and discussion from a technical review on pharmacology and toxicology of amphetamine and related designer drugs that took place on August 2 through 4, 1988, in Bethesda, MD. The review meeting was sponsored by the Biomedical Branch, Division of Preclinical Research, and the Addiction Research Center, National Institute on Drug Abuse. COPYRIGHT STATUS The National Institute on Drug Abuse has obtained permission from the copyright holders to reproduce certain previously published material as noted in the text. Further reproduction of this copyrighted material is permitted only as part of a reprinting of the entire publication or chapter. For any other use, the copyright holder’s permission is required. All other matieral in this volume except quoted passages from copyrighted sources is in the public domain and may be used or reproduced without permission from the Institute or the authors. -

Enhanced Reporting

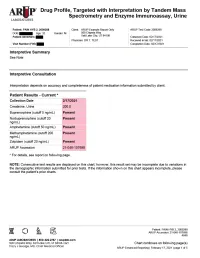

Drug Profile, Targeted with Interpretation by Tandem Mass Spectrometry and Enzyme Immunoassay, Urine Patient: PAIN HYB 2, 2009288 | Date of Birth: | Gender: M | Physician: DR T. TEST Patient Identifiers: | Visit Number (FIN): Drug Analyte Result Cutoff Notes Meperidine metabolite Not Detected 50 ng/mL normeperidine Tapentadol Not Detected 100 ng/mL --Tapentadol-o-sulfate Not Detected 200 ng/mL tapentadol metabolite AMPHETAMINE-LIKE, MASS SPEC Amphetamine Present 50 ng/mL eg, Vyvanse; also a metabolite of methamphetamine Methamphetamine Present 200 ng/mL d- and l- isomers are not distinguished by this test; may reflect Vicks inhaler, Desoxyn, Selegiline, or illicit source MDMA - Ecstasy Not Detected 200 ng/mL MDA Not Detected 200 ng/mL also a metabolite of MDMA and MDEA MDEA - Eve Not Detected 200 ng/mL Phentermine Not Detected 100 ng/mL Methylphenidate Not Detected 100 ng/mL eg, Ritalin, Dexmethylphenidate, Focalin, Concerta BENZODIAZEPINE-LIKE, MASS SPEC Alprazolam Not Detected 40 ng/mL eg, Xanax --Alpha-hydroxyalprazolam Not Detected 20 ng/mL alprazolam metabolite Clonazepam Not Detected 20 ng/mL eg, Klonopin --7-aminoclonazepam Not Detected 40 ng/mL clonazepam metabolite Diazepam Not Detected 50 ng/mL eg, Valium Nordiazepam Not Detected 50 ng/mL metabolite of chlordiazepoxide (Librium), clorazepate (Tranxene), diazepam, halazepam (Alapryl), prazepam (Centrax) and others Oxazepam Not Detected 50 ng/mL eg, Serax; also metabolite of nordiazepam and temazepam Temazepam Not Detected 50 ng/mL eg, Restoril; also a metabolite of diazepam Lorazepam Not Detected 60 ng/mL eg, Ativan Midazolam Not Detected 20 ng/mL eg, Versed Zolpidem Present 20 ng/mL eg, Ambien Reference interval Creatinine value (mg/dL) 200.0 20.0 - 400.0 mg/dL Patient: PAIN HYB 2, 2009288 ARUP Accession: 21-048-107698 4848 Chart continues on following page(s) ARUP Enhanced Reporting | February 17, 2021 | page 4 of 5 Drug Profile, Targeted with Interpretation by Tandem Mass Spectrometry and Enzyme Immunoassay, Urine Patient: PAIN HYB 2, 2009288 | Date of Birth | Gender: M | Physician: DR T. -

Gavinmclaughlin.Pdf (2.172Mb)

Accepted for publication in Drug Testing and Analysis 13.04.2018 Synthesis, analytical characterization and monoamine transporter activity of the new psychoactive substance 4- methylphenmetrazine (4-MPM), with differentiation from its ortho- and meta- positional isomers Gavin McLaughlin, a,b* Michael H. Baumann, c Pierce V. Kavanagh, a Noreen Morris, d John D. Power, a,b Geraldine Dowling, a,e Brendan Twamley, f John O’Brien, f Gary Hessman, f Folker Westphal, g Donna Walther, c and Simon D. Brandt h a Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, School of Medicine, Trinity Centre for Health Sciences, St. James’s Hospital, James’s Street, Dublin 8, D08W9RT, Ireland b Forensic Science Ireland, Garda Headquarters, Phoenix Park, Dublin 8, D08HN3X, Ireland c Designer Drug Research Unit, Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, 333 Cassell Drive, Suite 4400, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA d Department of Life & Physical Sciences, Faculty of Science and Health, Athlone Institute of Technology, Dublin Road, Athlone, Co. Westmeath, N37HD68, Ireland e Department of Life Sciences, School of Science, Sligo Institute of Technology, Ash Lane, Sligo, F91YW50, Ireland f School of Chemistry, Trinity College Dublin, College Green, Dublin 2, D02EV57, Ireland g State Bureau of Criminal Investigation Schleswig-Holstein, Section Narcotics/Toxicology, Mühlenweg 166, D-24116 Kiel, Germany h School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, Liverpool John Moores University, Byrom Street, Liverpool L3 3AF, UK *Correspondence to: Gavin McLaughlin, Department of Pharmacology & Therapeutics, School of Medicine, Trinity Centre for Health Sciences, St. James’s Hospital, James’s Street, Dublin 8, D08W9RT, Ireland. E-Mail: [email protected] Running title: Characterization of methylphenmetrazine isomers 1 Accepted for publication in Drug Testing and Analysis 13.04.2018 Abstract The availability of new psychoactive substances on the recreational drug market continues to create challenges for scientists in the forensic, clinical and toxicology fields. -

Amphetamine/Dextroamphetamine IR Generic

GEORGIA MEDICAID FEE-FOR-SERVICE STIMULANT AND RELATED AGENTS PA SUMMARY Preferred Non-Preferred Amphetamine/dextroamphetamine IR generic Adzenys ER (amphetamine ER oral suspension) Armodafinil generic Adzenys XR (amphetamine ER dispersible tab) Atomoxetine generic Amphetamine/dextroamphetamine ER (generic Concerta (methylphenidate ER/SA) Adderall XR) Dextroamphetamine IR tablets generic Aptensio XR (methylphenidate ER) Focalin (dexmethylphenidate) Clonidine ER generic Focalin XR (dexmethylphenidate ER) Cotempla XR (methylphenidate ER disintegrating Guanfacine ER generic tablet) Methylin oral solution (methylphenidate) Daytrana (methylphenidate TD patch) Methylphenidate CD/CR/ER generic by Lannett Desoxyn (methamphetamine) [NDCs 00527-####-##] and Kremers Urban [NDCs Dexmethylphenidate IR generic 62175-####-##] (generic Metadate CD) Dexmethylphenidate ER generic Methylphenidate IR generic Dextroamphetamine ER capsules generic Modafinil generic Dextroamphetamine oral solution generic Quillichew ER (methylphenidate ER chew tabs) Dyanavel XR (amphetamine ER oral suspension) Quillivant XR (methylphenidate ER oral suspension) Evekeo (amphetamine tablets) Vyvanse (lisdexamfetamine) Methamphetamine generic Zenzedi 5 mg, 10 mg IR tablets (dextroamphetamine) Methylphenidate IR chewable tablets generic Methylphenidate ER/SA (generic Concerta) Methylphenidate ER/LA/SR (generic Ritalin LA, Ritalin SR, Metadate ER) Methylphenidate ER/SA 72 mg generic Methylphenidate oral solution generic Mydayis (amphetamine/dextroamphetamine ER) Ritalin LA 10 mg -

Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences

Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences Series Editors Mark A. Geyer, La Jolla, CA, USA Bart A. Ellenbroek, Wellington, New Zealand Charles A. Marsden, Nottingham, UK For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/7854 About this Series Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences provides critical and comprehensive discussions of the most significant areas of behavioral neuroscience research, written by leading international authorities. Each volume offers an informative and contemporary account of its subject, making it an unrivalled reference source. Titles in this series are available in both print and electronic formats. With the development of new methodologies for brain imaging, genetic and genomic analyses, molecular engineering of mutant animals, novel routes for drug delivery, and sophisticated cross-species behavioral assessments, it is now possible to study behavior relevant to psychiatric and neurological diseases and disorders on the physiological level. The Behavioral Neurosciences series focuses on ‘‘translational medicine’’ and cutting-edge technologies. Preclinical and clinical trials for the development of new diagostics and therapeutics as well as prevention efforts are covered whenever possible. Cameron S. Carter • Jeffrey W. Dalley Editors Brain Imaging in Behavioral Neuroscience 123 Editors Cameron S. Carter Jeffrey W. Dalley Imaging Research Center Department of Experimental Psychology Center for Neuroscience University of Cambridge University of California at Davis Downing Site Sacramento, CA 95817 Cambridge CB2 3EB USA UK ISSN 1866-3370 ISSN 1866-3389 (electronic) ISBN 978-3-642-28710-7 ISBN 978-3-642-28711-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-28711-4 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2012938202 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2012 This work is subject to copyright. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

Toxicology Report Division of Toxicology Daniel D

Franklin County Forensic Science Center Office of the Coroner Anahi M. Ortiz, M.D. 2090 Frank Road Columbus, Ohio 43223 Toxicology Report Division of Toxicology Daniel D. Baker, Chief Toxicologist Casey Goodson Case # LAB-20-5315 Date report completed: January 28, 2021 A systematic toxicological analysis has been performed and the following agents were detected. Postmortem Blood: Gray Top Thoracic ELISA Screen Acetaminophen Not Detected ELISA Screen Barbiturates Not Detected ELISA Screen Benzodiazepines Not Detected ELISA Screen Benzoylecgonine Not Detected ELISA Screen Buprenorphine Not Detected ELISA Screen Cannabinoids See Confirmation ELISA Screen Fentanyl Not Detected ELISA Screen Methamphetamine Not Detected ELISA Screen Naltrexone/Naloxone Not Detected ELISA Screen Opiates Not Detected ELISA Screen Oxycodone/Oxymorphone Not Detected ELISA Screen Salicylates Not Detected ELISA Screen Tricyclics Not Detected Page 1 of 4 Casey Goodson Case # LAB-20-5315 GC/FID Ethanol Not Detected GC/MS Acidic/Neutral Drugs None Detected GC/MS Nicotine Positive GC/MS Cotinine Positive Reference Lab Delta-9-THC 13 ng/mL Reference Lab 11-Hydroxy-Delta-9-THC 1.2 ng/mL Reference Lab 11-Nor-9-Carboxy-Delta-9-THC 15 ng/mL Postmortem Urine: Gray Top Urine GC/MS Cotinine Positive This report has been verified as accurate and complete by ______________________________________ Daniel D. Baker, M.S., F-ABFT Cannabinoid quantitations in blood were performed by NMS Labs, Horsham, PA. Page 2 of 4 Casey Goodson Case # LAB-20-5315 Postmortem Toxicology Scope of Analysis Franklin County Coroner’s Office Division of Toxicology Enzyme Linked Immunosorbant Assay (ELISA) Blood Screen: Qualitative Presumptive Compounds/Classes: Acetaminophen (cut-off 10 µg/mL), Benzodiazepines (cut-off 20 ng/mL), Benzoylecgonine (cut-off 50 ng/mL), Cannabinoids (cut-off 40 ng/mL), Fentanyl (cut-off 1 ng/mL), Methamphetamine/MDMA (cut-off 50 ng/mL), Opiates (cut-off 40 ng/mL), Oxycodone/Oxymorphone (cut-off 40 ng/mL), Salicylates (50 µg/mL). -

ABSTRACT the Pdblications of the Marvel Comics Group Warrant Serious Consideration As .A Legitimate Narrative Enterprise

DOCU§ENT RESUME ED 190 980 CS 005 088 AOTHOR Palumbo, Don'ald TITLE The use of, Comics as an Approach to Introducing the Techniques and Terms of Narrative to Novice Readers. PUB DATE Oct 79 NOTE 41p.: Paper' presented at the Annual Meeting of the Popular Culture Association in the South oth, Louisville, KY, October 18-20, 19791. EDFS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage." DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature:,*Comics (Publications) : *Critical Aeading: *English Instruction: Fiction: *Literary Criticism: *Literary Devices: *Narration: Secondary, Educition: Teaching Methods ABSTRACT The pdblications of the Marvel Comics Group warrant serious consIderation as .a legitimate narrative enterprise. While it is obvious. that these comic books can be used in the classroom as a source of reading material, it is tot so obvious that these comic books, with great economy, simplicity, and narrative density, can be used to further introduce novice readers to the techniques found in narrative and to the terms employed in the study and discussion of a narrative. The output of the Marvel Conics Group in particular is literate, is both narratively and pbSlosophically sophisticated, and is ethically and morally responsible. Some of the narrative tecbntques found in the stories, such as the Spider-Man episodes, include foreshadowing, a dramatic fiction narrator, flashback, irony, symbolism, metaphor, Biblical and historical allusions, and mythological allusions.4MKM1 4 4 *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** ) U SOEPANTMENTO, HEALD.. TOUCATiONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE CIF 4 EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT was BEEN N ENO°. DOCEO EXACTLY AS .ReCeIVED FROM Donald Palumbo THE PE aSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGuN- ATING T POINTS VIEW OR OPINIONS Department of English STATED 60 NOT NECESSARILY REPRf SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF O Northern Michigan University EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY CO Marquette, MI.