The Art and Science of the Church Screen in Medieval Europe Boydell Studies in Medieval Art and Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Return of Result of Uncontested Election

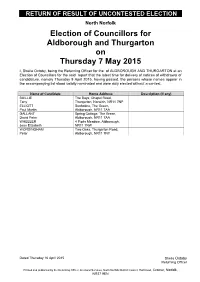

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION North Norfolk Election of Councillors for Aldborough and Thurgarton on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, Sheila Oxtoby, being the Returning Officer for the of ALDBOROUGH AND THURGARTON at an Election of Councillors for the said report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 9 April 2015, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BAILLIE The Bays, Chapel Road, Tony Thurgarton, Norwich, NR11 7NP ELLIOTT Sunholme, The Green, Paul Martin Aldborough, NR11 7AA GALLANT Spring Cottage, The Green, David Peter Aldborough, NR11 7AA WHEELER 4 Pipits Meadow, Aldborough, Jean Elizabeth NR11 7NW WORDINGHAM Two Oaks, Thurgarton Road, Peter Aldborough, NR11 7NY Dated Thursday 16 April 2015 Sheila Oxtoby Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Electoral Services, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9EN RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION North Norfolk Election of Councillors for Antingham on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, Sheila Oxtoby, being the Returning Officer for the of ANTINGHAM at an Election of Councillors for the said report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 9 April 2015, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) EVERSON Margra, Southrepps Road, Graham Fredrick Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NP JONES The Old Coach House, Antingham Independent Graham Hall, Cromer Road, Antingham, N. -

Tourism Benefit & Impacts Analysis in the Norfolk Coast Area Of

TOURISM BENEFIT & IMPACTS ANALYSIS IN THE NORFOLK COAST AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY APPENDICES May 2006 A Report for the Norfolk Coast Partnership Prepared by Scott Wilson NORFOLK COAST PARTNERSHIP TOURISM BENEFIT & IMPACTS ANALYSIS IN THE NORFOLK COAST AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY APPENDICES May 2006 Prepared by Checked by Authorised by Scott Wilson Ltd 3 Foxcombe Court, Wyndyke Furlong, Abingdon Business Park, Abingdon Oxon, OX14 1DZ Tel: +44 (0) 1235 468700 Fax: +44 (0) 1235 468701 Norfolk Coast Partnership Tourism Benefit & Impacts Analysis in the Norfolk Coast AONB Scott Wilson Contents 1 A1 - Norfolk Coast Management ...............................................................1 2 A2 – Asset & Appeal Audit ......................................................................12 3 A3 - Tourism Plant Audit..........................................................................25 4 A4 - Market Context.................................................................................34 5 A5 - Economic Impact Assessment Calculations ....................................46 Norfolk Coast Partnership Tourism Benefit & Impacts Analysis in the Norfolk Coast AONB Scott Wilson Norfolk Coast AONB Tourism Impact Analysis – Appendices 1 A1 - Norfolk Coast Management 1.1 A key aspect of the Norfolk Coast is the array of authority, management and access organisations that actively participate, through one means or another, in the use and maintenance of the Norfolk Coast AONB, particularly its more fragile sites. 1.2 The aim of the -

Church Building Terms What Do Narthex and Nave Mean? Our Church Building Terms Explained a Virtual Class Prepared by Charles E.DICKSON,Ph.D

Welcome to OUR 4th VIRTUAL GSP class. Church Building Terms What Do Narthex and Nave Mean? Our Church Building Terms Explained A Virtual Class Prepared by Charles E.DICKSON,Ph.D. Lord Jesus Christ, may our church be a temple of your presence and a house of prayer. Be always near us when we seek you in this place. Draw us to you, when we come alone and when we come with others, to find comfort and wisdom, to be supported and strengthened, to rejoice and give thanks. May it be here, Lord Christ, that we are made one with you and with one another, so that our lives are sustained and sanctified for your service. Amen. HISTORY OF CHURCH BUILDINGS The Bible's authors never thought of the church as a building. To early Christians the word “church” referred to the act of assembling together rather than to the building itself. As long as the Roman government did not did not recognize and protect Christian places of worship, Christians of the first centuries met in Jewish places of worship, in privately owned houses, at grave sites of saints and loved ones, and even outdoors. In Rome, there are indications that early Christians met in other public spaces such as warehouses or apartment buildings. The domus ecclesiae or house church was a large private house--not just the home of an extended family, its slaves, and employees--but also the household’s place of business. Such a house could accommodate congregations of about 100-150 people. 3rd-century house church in Dura-Europos, in what is now Syria CHURCH BUILDINGS In the second half of the 3rd century, Christians began to construct their first halls for worship (aula ecclesiae). -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

Gothic Beyond Architecture: Manchester’S Collegiate Church

Gothic beyond Architecture: Manchester’s Collegiate Church My previous posts for Visit Manchester have concentrated exclusively upon buildings. In the medieval period—the time when the Gothic style developed in buildings such as the basilica of Saint-Denis on the outskirts of Paris, Île-de-France (Figs 1–2), under the direction of Abbot Suger (1081–1151)—the style was known as either simply ‘new’, or opus francigenum (literally translates as ‘French work’). The style became known as Gothic in the sixteenth century because certain high-profile figures in the Italian Renaissance railed against the architecture and connected what they perceived to be its crude forms with the Goths that sacked Rome and ‘destroyed’ Classical architecture. During the nineteenth century, critics applied Gothic to more than architecture; they located all types of art under the Gothic label. This broad application of the term wasn’t especially helpful and it is no-longer used. Gothic design, nevertheless, was applied to more than architecture in the medieval period. Applied arts, such as furniture and metalwork, were influenced by, and followed and incorporated the decorative and ornament aspects of Gothic architecture. This post assesses the range of influences that Gothic had upon furniture, in particular by exploring Manchester Cathedral’s woodwork, some of which are the most important examples of surviving medieval woodwork in the North of England. Manchester Cathedral, formerly the Collegiate Church of the City (Fig.3), see here, was ascribed Cathedral status in 1847, and it is grade I listed (Historic England listing number 1218041, see here). It is medieval in foundation, with parts dating to between c.1422 and 1520, however it was restored and rebuilt numerous times in the nineteenth century, and it was notably hit by a shell during WWII; the shell failed to explode. -

GPR Survey: the Nave

The Ground Penetrating Radar survey in the Nave of Reading Abbey Church John Mullaney (December 2016) The West End The anomalous GPR lines at the west end of the nave of the Abbey church. When we first saw the GPR findings we were surprised to see the results at the west end of the nave (in the Forbury) which Stratascan classified as probably archaeology feature(s) –possibly related to the Abbey. — light blue on the map. I have marked these with two black arrows. probably archaeology feature –possibly related to the Abbey First of all it should be noted that these may be connected with some features totally unrelated to the Abbey. For instance they could be part of the defence system constructed during the 17th century Civil War. They may be footings of one of the walls that we know surrounded the late 18th century school next to the Inner Gateway (Jane Austen’s school). It is possible that they are part of the foundations for some buildings, such as the greenhouses, that appear to have been erected in the Forbury botanic gardens during the second half of the 19th century. However I have looked into the possibility that they may in fact be related to the Abbey; in other words whether there may be some explanation for their existence as part of the Abbey. I must emphasise that any one, or none, of the above may be the explanation and without intrusive archaeology or the discovery of some documentation relating to them, it is unlikely that we will ever know what they truly represent. -

What's a Dado Anyway?

What’s A Dado Anyway? hen we first found the thing back The dado found on Nikumaroro has a Win 1989 we took it to be the cover number of features which make it particularly of some kind of box. Although it didn’t interesting: look much like an airplane part it was, 1. Although evidently used in what appeared at least, made of aluminum and, at the to be the village’s carpentry shop as a sur- Research In Progress Research In Progress Research In Progress end of a grueling expedition which had face to hammer upon, it was never cut apart, found little else, that was good enough. broken or even seriously bent. Alone among In the catalogue of artifacts from NIKU I, acces- the various pieces of aircraft debris found sion number 2-18 is described as “aluminum on the island to date, 2-18 is a complete plate with riveted bands on edges; part of box?” structure, and yet nowhere does it carry a found at “Karaka village, Ritiati, structure 17 part number. (carpenter’s shop?).” After six years of research 2. Identical pry marks at each of the holes we’re now able to provide a somewhat better in the right angle bend suggest that it was description. originally attached with nails to wooden TIGHAR Artifact 2-18 is a structure known flooring. in aviation parlance as a “dado.” An internal fixture rather than part of the airframe, a dado 3. Several modifications made to the structure is a panel (often insulated) which covers and suggest that it was installed in a different protects the juncture of the aircraft’s cabin location and served a slightly different flooring and the fabric-covered interior wall. -

Chancel Choir Director JOB DESCRIPTION

JOB DESCRIPTION LaGrave Avenue Christian Reformed Church Position: Part-time Chancel Choir (adult) Director Summary LaGrave Avenue Christian Reformed Church, a growing and active 1900-member church established in 1887 and located in downtown, Grand Rapids, Michigan, seeks a part-time Chancel Choir director with an anticipated start date of summer, 2020. The director will lead a 70-member, all volunteer choir to enrich worship and bring praise and glory to God through the gift of singing. The director will work as part of a team of professional full and part-time staff and will advance the vision and goals of the church through their work and skills as an accomplished choral director. LaGrave’s music ministry, overseen by Minister of Music and Organist, Dr. Larry Visser, currently includes three vocal choirs, two handbell choirs, three assistant organists, several instrumentalists of all ages, with over 150 participants. The church’s 1996 five-manual, 108-rank Austin/Allen organ is among the finest in the region. The church also has an 8-foot Schimmel grand piano in the neo-Gothic 1960 sanctuary, which seats approximately 850. Additional information regarding LaGrave Avenue Christian Reformed Church may be gleaned from the church’s website: www.lagrave.org. Worship at LaGrave LaGrave Church is a Protestant church that is part of the Christian Reformed Church. Our theological roots are based in Calvinism. We believe that all things are under the sovereignty of Christ, and there is not one square inch of our world that is not being renewed and transformed under the Lordship and mind of Christ. -

Dado & Accessories

20-73 pages 8-28-06 8/30/06 11:21 AM Page 63 Dado Sets & Saw Blade Accessories Dado Sets 63 Whether you’re a skilled professional or a weekend hobbiest, Freud has a dado for you. The SD608, Freud’s Dial-A-Width Dado, has a patented dial system for easy and precise adjustments while offering extremely accurate cuts. The SD300 Series adds a level of safety not found in other manufacturers’ dadoes, while the SD200 Series provides the quality of cuts you expect from Freud, at an attractive price. 20-73 pages 8-28-06 8/30/06 11:21 AM Page 64 Dial-A-Width Stacked Dado Sets NOT A 1 Loosen SD600 WOBBLE Series DADO! 2 Turn The Dial 3 Tighten Features TiCo™ High Dado Cutter Heads Density Carbide Crosscutting Blend For Maximum Performance Chip Free Dadoes In Veneered Plywoods and Laminates The Dial-A-Width Dado set performs like a stacked dado, but Recommended Use & Cut Quality we have replaced the shims with a patented dial system and HARDWOOD: with our exclusive Dial hub, ensures accurate adjustments. SOFTWOOD: Each “click” of the dial adjusts the blade by .004". The Dial- A-Width dado set is easy to use, and very precise. For the CHIP BOARD: serious woodworker, there’s nothing better. PLYWOOD: • Adjusts in .004" increments. 64 LAMINATE: • Maximum 29/32" cut width. NON-FERROUS: • Adjusts easily to right or left operating machines. • Set includes 2 outside blades, 5 chippers, wrench and Application CUT QUALITY: carrying case. (Not recommended for ferrous metals or masonry) • Does not need shims. -

Blocks Weeds* up to 3 Months Guaranteed!

Blocks Weeds* Up To 3 Months Guaranteed! GARDEN Not for Use on Lawns STOP WEEDS* Before They Start! Precautionary Statements Hazards to Humans and Domestic Animals CAUTION Causes moderate eye irritation. Wear protective eyeware. Harmful if swallowed, inhaled or absorbed through the skin. Avoid contact with eyes, skin or clothing. Users should remove clothing immediately if pesticide gets inside. Then wash thoroughly and put on clean clothing. Prolonged or frequently repeated skin contact may cause allergic reaction in some individuals. Wash hands before eating, drinking, chewing gum, using tobacco or using the toilet. User Safety Recommendations • Users should wash hands before eating, drinking, chewing gum, using tobacco, or using the toilet. • Users should remove clothing immediately if pesticide gets inside. Then wash thoroughly and put on clean clothing. First Aid • Hold eye open and rinse slowly and gently with water for 15-20 minutes. Remove í para abrir | Presione volver a cerrar IF IN EYES: contact lenses, if present after the first 5 minutes, then continue rinsing eye. • Call a poison control center or doctor for treatment advice. • Call a poison control center or doctor immediately for treatment advice. Levante aqu IF SWALLOWED: • Have person sip a glass of water if able to swallow. • Do not induce vomiting unless told to do so by a poison control center or doctor. • • Do not give anything by mouth to an unconscious person. IF ON SKIN • Take off contaminated clothing. • Rinse skin immediately with plenty of water for 15-20 minutes. OR CLOTHING: • Call a poison control center or doctor for treatment advice. -

The Genius of the Roman Rite: the Reception and Implementation of the New Missal Pdf

FREE THE GENIUS OF THE ROMAN RITE: THE RECEPTION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NEW MISSAL PDF SJ Keith F. Pecklers | 160 pages | 29 Dec 2009 | Continuum Publishing Corporation | 9781441104038 | English | New York, United States The Genius of the Roman Rite, by Keith Pecklers SJ - PrayTellBlog It developed in the Latin language in the city of Rome and, while distinct Latin liturgical rites such as the Ambrosian Rite remain, the Roman Rite has over time been adopted almost everywhere in the Western Church. In medieval times there were very many local variants, even if they did not all amount to distinct rites, but uniformity grew as a result of the invention of printing and in obedience to the decrees of the — Council of Trent see Quo primum. Several Latin liturgical rites that survived into the 20th century were abandoned voluntarily in the wake of the Second Vatican Council. The Roman Rite is now the most widespread liturgical rite not only in the Latin Church but in Christianity as a whole. It is now normally celebrated in the form promulgated by Pope Paul VI in and revised by Pope John Paul II inbut use of the Roman Missal remains authorized as an extraordinary form under the conditions indicated in the papal document Summorum Pontificum. The Roman Rite is noted for its sobriety of expression. Concentration on the exact moment of change of the bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ has led, in the Roman Rite, to the consecrated Host and the chalice being shown to the people immediately after the Words of Institution. -

Saint Helen's Anglican Church

SAINT HELEN’S ANGLICAN CHURCH Founded 1911 This document is the continuation of a tradition of the gift of ministry by the Saint Helen’s Altar Guild. It is offered to the Glory of God, in gratitude for Altar Guild members – past, present and future, and particularly the Parish of Saint Helen’s. May we be given the grace to continue the work begun in our first century and to do the works of love that build community into the future. “This is our heritage, this that our fore bearers bequeathed us. Ours in our time, but in trust for the ages to be. A building so holy, His people most precious Faith and awe filled, possessors and stewards are we.” OUR EARLY HISTORY Because the High Altar is the focal point of St. Helen’s Church was built in 1911 during worship, Mr. Walker decided it should be a real estate boom and was consecrated by made from something special. He sent to the the Right Reverend A. J. de Pencier in Holy Land for some Cypress wood from the November of 1911. He was at that time the Mount of Olives and built the main altar and Archbishop of British Columbia. Much of the Lady Chapel altar. the surrounding land had already been subdivided and everyone thought that the Most altars have some form of adornment to area was destined to become the remind worshippers that it represents the metropolis of the Fraser Valley. It is a table of the Last Supper. Many churches had magnificent site and when the land was an antependium or Altar frontal made of originally logged off, it had an embroidered silk.