Print IR04112.Tif

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

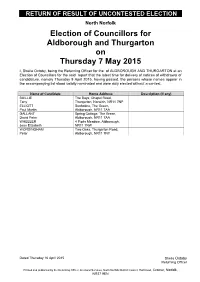

Return of Result of Uncontested Election

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION North Norfolk Election of Councillors for Aldborough and Thurgarton on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, Sheila Oxtoby, being the Returning Officer for the of ALDBOROUGH AND THURGARTON at an Election of Councillors for the said report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 9 April 2015, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BAILLIE The Bays, Chapel Road, Tony Thurgarton, Norwich, NR11 7NP ELLIOTT Sunholme, The Green, Paul Martin Aldborough, NR11 7AA GALLANT Spring Cottage, The Green, David Peter Aldborough, NR11 7AA WHEELER 4 Pipits Meadow, Aldborough, Jean Elizabeth NR11 7NW WORDINGHAM Two Oaks, Thurgarton Road, Peter Aldborough, NR11 7NY Dated Thursday 16 April 2015 Sheila Oxtoby Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Electoral Services, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9EN RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION North Norfolk Election of Councillors for Antingham on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, Sheila Oxtoby, being the Returning Officer for the of ANTINGHAM at an Election of Councillors for the said report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 9 April 2015, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) EVERSON Margra, Southrepps Road, Graham Fredrick Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NP JONES The Old Coach House, Antingham Independent Graham Hall, Cromer Road, Antingham, N. -

Tourism Benefit & Impacts Analysis in the Norfolk Coast Area Of

TOURISM BENEFIT & IMPACTS ANALYSIS IN THE NORFOLK COAST AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY APPENDICES May 2006 A Report for the Norfolk Coast Partnership Prepared by Scott Wilson NORFOLK COAST PARTNERSHIP TOURISM BENEFIT & IMPACTS ANALYSIS IN THE NORFOLK COAST AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY APPENDICES May 2006 Prepared by Checked by Authorised by Scott Wilson Ltd 3 Foxcombe Court, Wyndyke Furlong, Abingdon Business Park, Abingdon Oxon, OX14 1DZ Tel: +44 (0) 1235 468700 Fax: +44 (0) 1235 468701 Norfolk Coast Partnership Tourism Benefit & Impacts Analysis in the Norfolk Coast AONB Scott Wilson Contents 1 A1 - Norfolk Coast Management ...............................................................1 2 A2 – Asset & Appeal Audit ......................................................................12 3 A3 - Tourism Plant Audit..........................................................................25 4 A4 - Market Context.................................................................................34 5 A5 - Economic Impact Assessment Calculations ....................................46 Norfolk Coast Partnership Tourism Benefit & Impacts Analysis in the Norfolk Coast AONB Scott Wilson Norfolk Coast AONB Tourism Impact Analysis – Appendices 1 A1 - Norfolk Coast Management 1.1 A key aspect of the Norfolk Coast is the array of authority, management and access organisations that actively participate, through one means or another, in the use and maintenance of the Norfolk Coast AONB, particularly its more fragile sites. 1.2 The aim of the -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

St Botolph's Church Trunch

1 St Botolph’s Church Trunch An account of the history and special features of the Chancel including interventions and repairs . 2 *************************************************** *************************************************** ********************* PREAMBLE In 2006 St Botolph’s was inspected in accordance with the Inspection of Churches Measure, 1995 . It was discovered that there were major problems with the Chancel roof. The estimated cost of repairs was completely beyond the ability of the village to raise. The only recourse was to obtain grants from external agencies, especially English Heritage. The English Heritage procedures required the compilation of a research- based account of the history and maintenance record of the relevant part of a building. Restoration Committee member Anne Horsefield undertook to do the necessary research and to write the account. This was done and happily the grant application was successful. This account is a suitably amended version of the submission made to English Heritage. *************************************************** *************************************************** ********************* INTRODUCTION Blomefield’s History of Norfolk, Vol. VIII, 1800 gives the following description of St. Botolph’s Church, Trunch – “Church is dedicated to St.Botolph, and is a regular pile, with a nave, 2 aisles, and a chancel covered with lead and has a tower with 4 bells.” One hundred years later in 1900, Bryant, in his Norfolk Churches Vol. 5, The Hundred of North Erpingham , writes – “The church which stands nearly in the centre of the village is dedicated to St. Botolph and is a handsome edifice of flint with stone dressings in the Decorated and Perpendicular styles of architecture and one of the best in the neighbourhood.” Christobel M. Hoare affirms in her valuable book, The History of an East Anglian Soke, 1918 – “ Of all the Soke Churches none can really compare to St. -

Circular Walks East Norfolk Coast Introduction

National Trail 20 Circular Walks East Norfolk Coast Introduction The walks in this guide are designed to make the most of the please be mindful to keep dogs under control and leave gates as natural beauty and cultural heritage of the Norfolk coast. As you find them. companions to stretch one and two of the Norfolk Coast Path (part of the England Coast Path), they are a great way to delve Equipment deeper into this historically and naturally rich area. A wonderful Depending on the weather, some sections of these walks can array of landscapes and habitats await, many of which are be muddy. Even in dry weather, a good pair of walking boots or home to rare wildlife. The architectural landscape is expansive shoes is essential for the longer routes. Norfolk’s climate is drier too. Churches dominate, rarely beaten for height and grandeur than much of the country but unfortunately we can’t guarantee among the peaceful countryside of the coastal region, but sunshine, so packing a waterproof is always a good idea. If you there’s much more to discover. are lucky enough to have the weather on your side, don’t forget From one mile to nine there’s a walk for everyone here, whether sun cream and a hat. you’ve never walked in the countryside before or you’re a Other considerations seasoned rambler. Many of these routes lend themselves well to The walks described in these pages are well signposted on the trail running too. With the Cromer ridge providing the greatest ground, and detailed downloadable maps are available for elevation of anywhere in East Anglia, it’s a great way to get fit as each at www.norfolktrails.co.uk. -

North Norfolk District Council (Alby

DEFINITIVE STATEMENT OF PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY NORTH NORFOLK DISTRICT VOLUME I PARISH OF ALBY WITH THWAITE Footpath No. 1 (Middle Hill to Aldborough Mill). Starts from Middle Hill and runs north westwards to Aldborough Hill at parish boundary where it joins Footpath No. 12 of Aldborough. Footpath No. 2 (Alby Hill to All Saints' Church). Starts from Alby Hill and runs southwards to enter road opposite All Saints' Church. Footpath No. 3 (Dovehouse Lane to Footpath 13). Starts from Alby Hill and runs northwards, then turning eastwards, crosses Footpath No. 5 then again northwards, and continuing north-eastwards to field gate. Path continues from field gate in a south- easterly direction crossing the end Footpath No. 4 and U14440 continuing until it meets Footpath No.13 at TG 20567/34065. Footpath No. 4 (Park Farm to Sunday School). Starts from Park Farm and runs south westwards to Footpath No. 3 and U14440. Footpath No. 5 (Pack Lane). Starts from the C288 at TG 20237/33581 going in a northerly direction parallel and to the eastern boundary of the cemetery for a distance of approximately 11 metres to TG 20236/33589. Continuing in a westerly direction following the existing path for approximately 34 metres to TG 20201/33589 at the western boundary of the cemetery. Continuing in a generally northerly direction parallel to the western boundary of the cemetery for approximately 23 metres to the field boundary at TG 20206/33611. Continuing in a westerly direction parallel to and to the northern side of the field boundary for a distance of approximately 153 metres to exit onto the U440 road at TG 20054/33633. -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of Henry High 1 Henry High b: Abt. 1745 . +Elizabeth Fill m: 06 Aug 1764 in Briston .... 2 Benjamin High b: 09 Sep 1764 in Briston d: 12 Nov 1848 in Cley next the Sea ........ +Mary Wilkinson b: 1769 m: 29 Dec 1791 in Booton d: 19 Apr 1829 in Cley next the Sea ........... 3 Benjamin High b: 29 Apr 1792 in Booton d: Abt. Jun 1879 in Walsingham District ............... +Mary Josh b: Abt. 1792 in Mattishall d: Abt. Dec 1880 in Walsingham District .................. 4 Benjamin High b: 03 Feb 1817 in Glandford d: Bef. 1841 .................. 4 Henry High b: 01 Apr 1818 in Glandford d: 05 Nov 1886 in Wood Norton ..................... +Mary Ann Pitcher b: Abt. 1824 in Weybourne m: Abt. Jun 1845 in Walsingham District ........................ 5 Benjamin High b: 07 Sep 1845 in Weybourne d: 28 Jul 1851 in Wiveton ........................ 5 Mary Elizabeth High b: Abt. 1847 in Wiveton ........................ 5 William Henry High b: 10 Sep 1854 in Wiveton Norfolk ............................ +Elizabeth Handley b: Abt. 1858 in Carlton Notts m: Abt. Dec 1876 in Leeds District ............................... 6 Ada Florry High b: Abt. 1878 in Wortley Leeds Yorkshire ................................... +Henry Knaggs b: Abt. 1879 m: Abt. Sep 1907 in Hunslet District ............................... 6 Gertrude Annie High b: Abt. Dec 1884 in Hunslet Leeds ............................... 6 William Martin High b: Abt. Mar 1887 in Hunslet Leeds ............................... 6 Nellie High b: Abt. Sep 1889 in Hunslet Leeds .................. *2nd Wife of Henry High: ..................... +Charlotte Edwards b: Abt. 1857 in Mattishall m: Abt. Sep 1880 in Mitford District ........................ 5 Beatrice High b: Abt. 1878 in Wood Norton ....................... -

1 Hall Farm Barn Mundesley Road, Trunch, Norfolk, NR28 0QB INTRODUCTION: Street Which Joins the Mundsley Road

1 Hall Farm Barn Mundesley Road, Trunch, Norfolk, NR28 0QB INTRODUCTION: Street which joins the Mundsley Road. The Barn is accessed by turning right at the Cruso & Wilkin are delighted to be instructed to market a stunning unconverted Grade II grass triangle on Gunthorpe Lane then immediately left. Listed Barn. The barn is believed to date from the late 16th Century. The Barn has the benefit of Planning Permission from the North Norfolk District Council as outlined within Tenure and Possession: these Particulars. The Barn is offered For Sale Freehold with the benefit of Vacant Possession. This barn has the potential to be a unique and extremely special barn conversion hidden Method of Sale: away just a couple of miles from the Norfolk coastline. The Barn is offered For Sale via Private Treaty. The Vendor and their Agent reserve the right to invite best and final offers and/or offer the property for sale by private auction if PARTICULARS: there is a substantial level of interest. Location and Situation: The popular Village of Trunch is situated approximately 2 miles from the north east Viewing: Norfolk coastline and circa 3 miles north of the market town of North Walsham. Trunch Viewing is accompanied and strictly by prior appointment only with the Vendor’s Agent, has a Post Office / Village Shop, Church, Chapel, Public House and many attractive Cruso & Wilkin. Tel. 01553 691691. footpath walks . Health and Safety: North Walsham has a number of shops and amenities. There is also a Railway Station Given the potential hazards and for your own personal safety we would ask you to be as which provides direct rail travel to Norwich. -

STATEMENT of PERSONS NOMINATED Election of Parish

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED North Norfolk Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Councillor for Aldborough and Thurgarton Reason why Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer no longer nominated* BAILLIE The Bays, Chapel Murat Anne M Tony Road, Thurgarton, Norwich, NR11 7NP ELLIOTT Sunholme, The Elliott Ruth Paul Martin Green, Aldborough, NR11 7AA GALLANT Spring Cottage, The Elliott Paul M David Peter Green, Aldborough, NR11 7AA WHEELER 4 Pipits Meadow, Grieves John B Jean Elizabeth Aldborough, NR11 7NW WORDINGHAM Two Oaks, Freeman James H J Peter Thurgarton Road, Aldborough, NR11 7NY *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. The persons above against whose name no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. Dated: Friday 10 April 2015 Sheila Oxtoby Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Electoral Services, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9EN STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED North Norfolk Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Councillor for Antingham Reason why Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer no longer nominated* EVERSON Margra, Southrepps Long Trevor F Graham Fredrick Road, Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NP JONES The Old Coach Independent Bacon Robert H Graham House, Antingham Hall, Cromer Road, Antingham, N. Walsham, NR28 0NJ LONG The Old Forge, Everson Graham F Trevor Francis Elderton Lane, Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NR LOVE Holly Cottage, McLeod Lynn W Steven Paul Antingham Hill, North Walsham, Norfolk, NR28 0NH PARAMOR Field View, Long Trevor F Stuart John Southrepps Road, Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NP *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. -

NORFOLK. FAR 701 Foulger George (Exors

TRADES DIREC'rORY. J NORFOLK. FAR 701 Foulger George (exors. of), Beding- Gallant James, Moulton St. Michael, Gee Wm. Sunny side & Crow Green ham, Bungay Long Stratton R.S.O farm, Stratton St. Mary, Long Foulger Horace, Snetterton, Thetford Gallant John, Martham, Yarmouth Stra.tton R.S.O Fowell R. Itteringham,Aylsham R.S.O Gallant T. W. Rus.hall, Scole R.S.O Gent Thomas & John, Marsh! Terring Fowell William, Corpusty, Norwich Galley Willia.m, Bintry, Ea. Dereham ton St. Clement, Lynn Fo::r: Charles, Old Hall fann,Methwold, Gamble Henry, Rougbam, Swaffha• Gent George, Marsh, Terrington Si- Stoke Ferry S.O Gamble Hy. Wood Dalling, Norwiclt Clement, Lynn Fo::r: F . .Aslact<>n,Long Stratton R.S.O Gamble Henry Barton, Eau Brink hall, George He.rbert, Rockland All Saints, Fo::r: George, Roughwn, Norwich Wiggenhall St. Mary the Virgia, Attleborough Fox Henry, Brisley, East Dereham Lynn George J. Potter-Heigham, Yarmouth Fo::r: Jas. Great Ellingbam, Attleboro' Gamble Henry Rudd, The Lodge,Wig- Gibbons R. E. West Bradenham,Thtfrd Fox Jn. Swanton Morley, E. Dereham genhall St. Mary the Virgin, Lyna Gibbons John, Wortwell, Harleston Fo::r: Lee, Sidestrand, Oromer Gamble W. Terrington St. Joha, Gibbon& Samuel, Scottow, Norwich Fo::r: R. White ho. Clenchwarton,Lynn Wisbech Gibbons William, Scottow, Norwich Fox Robert, Roughton, Norwich Gamble William, Summer end, East Gibbons W. R. Trunch, N. Walsham Po::r: Samuel, Binham, Wighton R.S.O Walton, Lynn Gibbs & Son, Hickling, Norwich Fo::r: Thomas, Elsing, Ea11t Dereham Gamble Wm. North Runcton, Lyna Gibbs A. G. Guestwick, Ea. Deraham Po::r: W. -

Trunch Parish Council

Trunch Parish Council An Ordinary Meeting of Trunch Parish Council was held in the Methodist Church Community Room on Wednesday 5th June. The meeting was attended by the Clerk, the County Councillor, the NNDC’s Planning Policy Officer, eight Councillors and thirteen members of the public. Mark Ashwell, the North Norfolk District Councils Planning Policy Officer provided a candid and informative presentation of the First Draft of the Local Plan covering the period from 2016 until 2036. He explained the reason and philosophy behind the need for more housing development in North Norfolk. Developments in Large Growth Towns (e.g. North Walsham and Cromer), Small Growth Towns (e.g. Holt and Sheringham) and Large Growth Villages (e.g. Mundesley) are included in Part 1 of the Plan. The target by 2036 is to build 11,000 more dwellings. He also explained that the recent house building and barn conversions in Trunch would not be included in any future development for Trunch. Around 400 new homes are planned to be built in twenty three Small Growth Villages (e.g Trunch). The number of new allocations for Trunch will not be known until the issue of Part 2 of the Plan in Spring next year. However, a ‘Call for Sites’ in the twenty three villages, including Trunch, has received registrations from land owners. In view of the implications of the developments and the likely effect on local services it was agreed to hold a Public Meeting on 12th July in order for the Parish Council to obtain the views of residents such that a reasoned response to the Plan can be formulated and sent to the District Council. -

North Norfolk Landscape Character Assessment Contents

LCA cover 09:Layout 1 14/7/09 15:31 Page 1 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT NORTH NORFOLK Local Development Framework Landscape Character Assessment Supplementary Planning Document www.northnorfolk.org June 2009 North Norfolk District Council Planning Policy Team Telephone: 01263 516318 E-Mail: [email protected] Write to: Planning Policy Manager, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, NR27 9EN www.northnorfolk.org/ldf All of the LDF Documents can be made available in Braille, audio, large print or in other languages. Please contact 01263 516318 to discuss your requirements. Cover Photo: Skelding Hill, Sheringham. Image courtesy of Alan Howard Professional Photography © North Norfolk Landscape Character Assessment Contents 1 Landscape Character Assessment 3 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 What is Landscape Character Assessment? 5 2 North Norfolk Landscape Character Assessment 9 2.1 Methodology 9 2.2 Outputs from the Characterisation Stage 12 2.3 Outputs from the Making Judgements Stage 14 3 How to use the Landscape Character Assessment 19 3.1 User Guide 19 3.2 Landscape Character Assessment Map 21 Landscape Character Types 4 Rolling Open Farmland 23 4.1 Egmere, Barsham, Tatterford Area (ROF1) 33 4.2 Wells-next-the-Sea Area (ROF2) 34 4.3 Fakenham Area (ROF3) 35 4.4 Raynham Area (ROF4) 36 4.5 Sculthorpe Airfield Area (ROF5) 36 5 Tributary Farmland 39 5.1 Morston and Hindringham (TF1) 49 5.2 Snoring, Stibbard and Hindolveston (TF2) 50 5.3 Hempstead, Bodham, Aylmerton and Wickmere Area (TF3) 51 5.4 Roughton, Southrepps, Trunch