WWF Paper-Realising Sust Palm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOS Final Technical Report

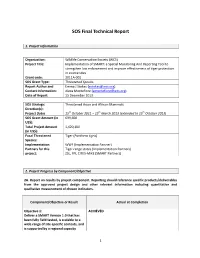

SOS Final Technical Report 1. Project Information Organization: Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Project Title: Implementation of SMART: a Spatial Monitoring And Reporting Tool to strengthen law enforcement and improve effectiveness of tiger protection in source sites Grant code: 2011A-001 SOS Grant Type: Threatened Species Report Author and Emma J Stokes ([email protected]) Contact Information: Alexa Montefiore ([email protected]) Date of Report: 15 December 2013 SOS Strategic Threatened Asian and African Mammals Direction(s): Project Dates 15th October 2011 – 15th March 2013 (extended to 15th October 2013) SOS Grant Amount (in 699,600 US$): Total Project Amount 1,420,100 (in US$): Focal Threatened Tiger (Panthera tigris) Species: Implementation WWF (Implementation Partner) Partners for this Tiger range states (Implementation Partners) project: ZSL, FFI, CITES-MIKE (SMART Partners) 2. Project Progress by Component/Objective 2A. Report on results by project component. Reporting should reference specific products/deliverables from the approved project design and other relevant information including quantitative and qualitative measurement of chosen indicators. Component/Objective or Result Actual at Completion Objective 1: ACHIEVED Deliver a SMART Version 1.0 that has been fully field-tested, is scalable to a wide range of site-specific contexts, and is supported by a regional capacity 1 building strategy. Result 1.1: - SMART 1.0 publicly released Feb 2013. A SMART system that is scalable, fully - Two subsequent updates released based on early field-tested and supported by a regional field testing (current version 1.1.2) capacity building strategy is in place in 9 - Software translated into Thai, Vietnamese and implementation sites. -

Carrying Capacity Estimation of Sumatran Elephant Habitat (Elephas Maximus Sumatranus T) in Tesso Nilo National Park

J Anim Behav Biometeorol (2020) 8:41-48 ISSN 2318-1265 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Carrying capacity estimation of Sumatran elephant habitat (Elephas maximus sumatranus T) in Tesso Nilo National Park Defri Yoza ▪ Yusni Ikhwan Siregar ▪ Aras Mulyadi ▪ Sujianto D Yoza (Corresponding author) YI Siregar ▪ A Mulyadi ▪ Sujianto Department of Forestry, Agricultural faculty, University of Department of Environmental Science, Graduate Program, Riau, Pekanbaru, Indonesia. University of Riau, Pekanbaru, Indonesia. email: [email protected] Received: June 10, 2019 ▪ Accepted: August 14, 201 9 ▪ Published Online: September 30, 2019 Abstract Forest encroachment reduces elephant habitat area namely savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana africana) and while oil palm plantations and industrial plantations reduce forest elephant (Loxodonta africana cyclotis) (Sukumar and even cut the elephant roaming area. This study aims to 2003). The species Elephas maximus is also found on the estimate the carrying capacity of elephant habitat in Tesso island of Sumatra with a young of the type Sumatranus so that Nilo National Park, Indonesia. Data collection on elephant it becomes Elephas maximus sumatranus. populations uses direct and indirect surveys. Direct surveys On Sumatra Island, Elephas maximus sumatranus are carried out by direct encounter with the elephants and became an enemy of oil palm farmers but was protected by counting is done at the meeting. The indirect survey was law as a protected animal. On the one hand, these Elephants carried out in two ways, namely by counting dung and traces are considered pests, but on the other hand, their existence of elephants as well as interviews with mahout and the should not be disturbed by the community because they could community. -

Communities and Conservation 50 Inspiring Stories: a Gift from WWF to Indonesia

Communities and Conservation 50 Inspiring Stories: A Gift from WWF to Indonesia Editors: Cristina Eghenter, M. Hermayani Putera and Israr Ardiansyah I Editors: Cristina Eghenter, M. Hermayani Putera and Israr Ardiansyah Cover Photo: Jimmy Syahirsyah/WWF-Indonesia Cover Design: Try Harta Wibawanto Design and Layout: Bernard (Dipo Studio) Try Harta Wibawanto Published: October 2015 by WWF-Indonesia. All reproduction, in whole or in part, must credit the title and the publisher as the copyright holder. © Text 2012 WWF-Indonesia WWF is one of the largest and most experienced independent conservation organizations, with over 5 million supporters and a global network active in more than 100 countries. WWF’s mission is to stop degradation of the planet’s natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature, by conserving the world’s biological diversity, ensuring that use of renewable resources is sustainable, and promoting the reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption. The vision of WWF-Indonesia for biodiversity conservation is: Indonesia’s ecosystems and biodiversity are conserved, sustainably and equitably managed for the well-being of present and future generations. Why we are here To stop the degradation of the planet’s natural environment and to build a future in which human live in harmony with nature. http://www.wwf.or.id This publication should be cited as: Eghenter, C. Putera, M.H. Ardiansyah I (eds) (2015) Communities and Conservation: 50 Inspiring Stories a gift from WWF to Indonesia. WWF-Indonesia II Communities and Conservation 50 Inspiring Stories: A Gift from WWF to Indonesia III Acknowledgments We wish to extend our heartfelt thanks to our project staff, the storytellers of this book. -

Global Aspirations to Local Actions: Can Orangutan Save Tropical Rainforest ? E

Global Aspirations to Local Actions: Can Orangutan Save Tropical Rainforest ? E. Purwanto 1 G.A. Limberg 2 Abstract Flagship species are important icons for the international conservation lobby, because they are appealing, and need intact ecosystems for their survival. Orangutans are one such flagship species. However, its habitat continues to be threatened by development plans of both governments and companies. A pulp and paper company adjacent to the Kutai national park in East Kalimantan, complained that orangutans are increasingly a problem, destroying the young acacia trees of the plantation. To explore possible solutions they initiated discussion including a range of stakeholders to develop an orangutan survival action plan. This study presents the views of stakeholders on the importance of orangutans and conservation in general. We also examine examples from elsewhere in Indonesia to analyze the different approaches used by and incentives for stakeholders to participate in saving the flagship species and its habitat. We conclude that international lobby and attention to flagship species does not reach the local stakeholders nor automatically translate into similar vision of stakeholders closest linked to the use and management of the flagship species habitat. This lack of interest and understanding leads to denial of the problem, limited understanding of the extend of the problem or partial solutions. International lobby will put pressure on big companies to adapt better practices, but the risks exists that they look for easy solutions and transfer the responsibility. The local government and population often perceive conservation as contradictionary to development and of limited direct value. What is needed in improve joint responsibility for public good such as conservation area? A mix of attention, incentives and pressure will be needed to ensure that key stakeholders to go beyond quick and superficial solutions. -

IMPACT of POPULATION MIGRATION in TESSO NILO NATIONAL PARK RIAU PROVINCE Harapan Tua RFS and Mimin Sundari Nasution Lecturer Of

Sosiohumaniora: Jurnal Ilmu-ilmu Sosial dan Humaniora Vol, 23, No. 1, March 2021: 72-79 ISSN 1411 - 0903 : eISSN: 2443-2660 IMPACT OF POPULATION MIGRATION IN TESSO NILO NATIONAL PARK RIAU PROVINCE Harapan Tua RFS and Mimin Sundari Nasution Lecturer of Public Administration Faculty Social Science and Political Science University of Riau Email: [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT. The Tesso Nilo National Park is a conservation area that should be free from settlements and plantations. The migrants who come to the TNTN area are generally tough farmers who come from various ethnic groups such as Javanese, Batak, Palembang, even now there are Toro Bali. This study aims to look at Population Migration in Toro Jaya Hamlet, in the TNTN Area and the Impact of Population Migration on Forest Damage in the TNTN Area. This research uses a qualitative approach. Key Research Informants were selected by purposive and then using the snow ball sampling technique to determine the next informant. The method of data collection was done by means of in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, documentation. Then the data is analyzed based on the Interactive analysis model. The results show that population migration in TNTN has increased significantly coupled with the birth rate of the population, which on average are couples of productive age, which has made fertile land for population growth in TNTN. The smooth accessibility with the entry of public transportation vehicles (buses) to TNTN, especially Dusun Toro Jaya, coupled with the production of their “oil palm” plantation crops have also become a pull factor for many people to migrate to TNTN. -

Democracy in the Forests

COVER AID THAT WORKS A portrait of Indonesia’s MULTISTAKEHOLDER FORESTRY PROGRAMME Multistakeholder Forestry Programme is co-managed by the Ministry of Forestry and funded by the Department for International Development, UK Ministry of Department for Forestry International Development UK AID THAT WORKS A portrait of Indonesia’s MULTISTAKEHOLDER FORESTRY PROGRAMME by Charlie Pye-Smith December 2006 Acknowledgements A great many people have helped to shape this book. Special thanks go to Mike Harrison, the UK Co-director of the Multistakeholder Forestry Programme (MFP), for overseeing the project and accompanying me on many of my research trips, and to his predecessor, Yvan Biot, who commissioned the first round of stories in 2004. MFP facilitators, both in Jakarta and the regions, were generous with both their time and their considerable knowledge. Thanks go to Adjat Sudradjat, David W Brown, Nonette Royo, Prudensius Maring and Tri Nugroho; and to the six regional facilitators, Anas Nikoyan, Hasbi Berliani, Irfan Bakhtiar, Maria Elena Latumahina, Rudi Syaf and Swary Utami Dewi. The regional facilitators went to great lengths to organise field visits. MFP's first Indonesian Co-director, Sutaryo Suriamihardja, and staff from the Ministry of Forestry seconded to MFP, Agus Justianto, Hardjono Hardjowitjitro and Yuyu Rahayu, provided a significant input to this book. I also received great support from Gus Mackay and his administrative team in Jakarta, and during my first round of visits, in 2004, Angel Manembu acted as an admirable guide and translator. Lise Schofield Hermawan and Irfan Toni Herlambang worked against very tight deadlines to design and produce Aid that Works, and they were ably assisted by Anthony Lambert, the copy editor. -

Recent Publications on Asian Elephants

News and Briefs Gajah 51 (2020) 47-71 Recent Publications on Asian Elephants Compiled by Jennifer Pastorini Centre for Conservation and Research, Tissamaharama, Sri Lanka Anthropologisches Institut, Universität Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] If you need additional information on any of the urine samples collected on three consecutive articles, please feel free to contact me. You can days. Four elephants (31%) were confrmed to also let me know about new (2020) publications shed pathogenic leptospires in their urine. DNA on Asian elephants. sequencing followed by phylogenetic distance measurements revealed that all positive elephants A. Abdullah, A. Sayuti, H. Hasanuddin, M. Affan were infected with L. interrogans. This study & G. Wilson reveals the possibility that elephants act as a People’s perceptions of elephant conservation source of infection of leptospires to humans and and the human-elephant confict in Aceh Jaya, recommends the screening of all domesticated Sumatra, Indonesia elephants that are in close contact with humans European J. of Wildlife Research 65 (2019) e69 for the shedding of pathogenic leptospires. © Abstract. No permission to print the abstract. 2019 Reprinted with permission from Elsevier . T.P.J. Athapattu, B.R. Fernando, N. Koizumi & K.A. Backues & E.B. Wiedner C.D. Gamage Recommendations for the diagnosis, treatment Detection of pathogenic leptospires in the and management of tuberculosis, Mycobacte- urine of domesticated elephants in Sri Lanka rium tuberculosis, in elephants in human care Acta Tropica 195 (2019) 78-82 International Zoo Yearbook 53 (2019) 116-127 Abstract. Leptospirosis is a globally common Abstract. African elephants Loxodonta africana zoonotic infectious disease in humans and and Asian elephants Elephas maximus are both animals. -

Sumatra's Forests, Their Wildlife and the Climate

Sumatra’s Forests, their Wildlife and the Climate Windows in Time: 1985, 1990, 2000 and 2009 Sumatra’s Forests, their Wildlife and the Climate Windows in Time: 1985, 1990, 2000 and 2009 A quantitative assessment of some of Sumatra’s natural resources submitted as technical report by invitation to the National Forestry Council (DKN) and to the National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS) of Indonesia WWF-Indonesia Jakarta, Indonesia July 2010 Authors Yumiko Uryu, Consultant to World Wildlife Fund, Washington DC, USA Elisabet Purastuti, Consultant to WWF-Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia Yves Laumonier, CIRAD-CIFOR, Bogor, Indonesia Sunarto, WWF-Indonesia PhD Fellow, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University, Blacksburg, USA Setiabudi, SEAMEO-BIOTROP, Bogor, Indonesia Arif Budiman, WWF-Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia Kokok Yulianto, WWF-Indonesia, Riau, Indonesia Anggoro Sudibyo, WWF-Indonesia, Riau, Indonesia Oki Hadian, WWF-Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia Dian Achmad Kosasih, WWF-Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia Michael Stüwe, World Wildlife Fund, Washington DC, USA Reviewers (in alphabetical order): Ajay Desai (Co-chair IUCN Species Survival Commission Asian Elephant Specialist Group) Christy Williams (WWF International) Florian Siegert (University of Munich, GeoBio-Center) Hariadi Kartodihardjo (Institut Pertanian Bogor) Hariyo T. Wibisono (Wildlife Conservation Society - Indonesia Program) Ian Singleton (Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Programme, PanEco-YEL) John Payne (WWF Malaysia) Kerry Crosbie (Project Director, Asian Rhino Project) Kristin Nowell (Red List Coordinator, IUCN Species Survival Commission Cat Specialist Group) Matthew Linkie (Fauna & Flora International) Peter Pratje (Frankfurt Zoological Society) Simon Hedges (Co-chair IUCN Species Survival Commission Asian Elephant Specialist Group) Sri Suci Utami Atmoko (Universitas Nasional) Susie Elis (Executive Director, International Rhino Foundation) Photo on front cover: Natural forest of Bukit Tigapuluh National Park, Sumatra, Indonesia © Mast Irham / WWF-Indonesia. -

2012, the USFWS Awarded 39 New Grants from the Asian Elephant Conservation Fund Totaling $1,926,072.00, Which Was Matched by $2,306,754.00 in Leveraged Funds

Wildlife Without Borders - Asian Elephant Conservation Fund In 2012, the USFWS awarded 39 new grants from the Asian Elephant Conservation Fund totaling $1,926,072.00, which was matched by $2,306,754.00 in leveraged funds. Field projects in eight countries (in alphabetical order below) will be supported, in addition to one project that involves multiple countries. BURMA Conservation of wild elephants and elephant habitat in Hukaung Valley, Burma: Year 5. ASE-0582 Wildlife Conservation Society Grant# F12AP00956 FWS: $60,195 Leveraged Funds: $60,206 Location: Hukaung Valley, Burma This project aims to do the following: (1) to continue law enforcement activities using Elephant Patrol Units; (2) to increase the forest department's ability to monitor elephants and integrate this system with another existing system; and (3) to upgrade the current patrol system to use Management Information SysTems (MIST) and CITES Monitoring Illegal Killing of Elephants (MIKE). CAMBODIA Asian elephant conservation education through Kouprey Express. ASE-0575 Wildlife Alliance Grant# F12AP00344 FWS: $56,832 Leveraged Funds: $212,495 Location: Cardamom Mountains, Cambodia The purpose of this project is to continue to provide environmental education to rural and impoverished communities living amongst wild Asian elephants in the Cardamom Mountains of Cambodia. The threats addressed include habitat loss, poaching, and wildlife trade. Northern Plains of Cambodia elephant conservation project: Phase 3. ASE-0579 Wildlife Conservation Society Grant# F12AP00345 FWS: $55,234 Leveraged Funds: $55,275 Location: Cambodia This project aims to reduce human-elephant conflict by increasing awareness within local communities, military personnel, and others to reduce threats to elephants and their habitats. -

Wwf Id Ar 2013 Final.Pdf

Contributors Adji Santoso Halim Muda Rizal Maria Valentina Patricia Dini Setyorini Cristina Eghenter Indiani Saptiningsih Margareth Meutia Rusyda Deli Desmarita Murni Irma Herwinda Nazir Foead Susilowati Lestari Dewi Satriani Irwan Gunawan Neny Legawati Verena Puspawardani Diah R Sulistiowati Linda Sukandar Noverica Widjojo Devy Suradji Maya Bellina Nyoman Iswarayoga Supervisory Board Arief T. Surowidjojo (chairperson) Martha Tilaar Advisory Board Pia Alisjahbana (chairperson) Arifin M. Siregar Djamaludin Suryohadikusumo A.R. Ramly Executive Board Kemal Stamboel (chairperson) Shinta Widjaja Kamdani Rizal Malik Tati Darsoyo Directors Dr. Efransjah - CEO Nazir Foead - Conservation Director Klaas Jan Teule - Programme Development & Sustainability Director Devy Suradji - Marketing Director Anwar Purwoto - Forest, Freshwater, Terrestrial Species Director Wawan Ridwan - Marine & Marine Species Director Benja Mambai - Papua Director Nyoman Iswarayoga - Climate & Energy Director Prof. Hadi S. Alikodra - Senior Advisor Edited by Vivien Kim Concept & Design by ISBG CommuniAction Front cover photo © WWF-Indonesia/Lie Tangkepayung Published in July 2014 by WWF-Indonesia, Jakarta © Text 2013 WWF All rights reserved WWF is one of the largest and most experienced independent conservation organizations, with over 5 million supporters and a global network active in more than 100 countries. WWF’s mission is to stop degradation of the planet’s natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature, by conserving the world’s -

Annual Report 2013

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 TROPICAL FOREST CONSERVATION ACTION FOR SUMATERA Administered by KEHATI-The Indonesian Biodiversity Foundation 2014 TFCA-‐Sumatera Annual Report 13 20 1 Scenery of Hutan Desa Nagari Simanau,. Photo by Heriyadi Asyari. Photo cover by Ali Sofiawan, Nety Riana Sari, Irsan and doc Bumi Raya Consulting TFCA-Sumatera Annual Report 2013 2 Oversight Committee TFCA-‐SUMATERA Chair person: Jatna Supriatna Secretary: M.S. Sembiring Ministry of Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia Representative: Hartono OCTM: Nining Ngudi Purnamaningtyas/Agus Yulianto United States Agency For International Development Representative: Aurelia Micko Alternate: John F. Hansen OCTM: Antonius P. Djogo Conservation International -‐ Indonesia Program Representative: Jatna Supriatna OCTM: Tri Rooswiadji KEHATI-‐ The Indonesian Biodiversity Foundation Representative: Erna Witoelar Alternate: Hariadi Kartodiharjo OCTM: Arnold Sitompul Syiah Kuala University – Unsyiah Representative: Darusman Rusin Indonesia Business Links Representative: Sri Indrastuti Hadiputranto Transparency International – Indonesia Representative: Rezki Sri Wibowo 3 TFCA-Sumatera Annual Report 2013 List of Abbreviation ALeRT Aliansi Lestari Rimba Terpadu, Alliance of Integrated Forest Conservation Bappenas Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan , Nasional National Development Planning Bitra Bina Keterampilan Pedesaan BBS Bukit Barisan Selatan BKSDA Balai Konservasi Sumberdaya Alam, Natural Resource Conservation Office, is a Technical Implementation Unit of the Directorate General of Forest -

Sustainable Mountain Development in South East Asia and Pacific from Rio 1992 to Rio 2012 and Beyond

Regional Report Sustainable Mountain Development in South East Asia and Pacific From Rio 1992 to Rio 2012 and beyond 2012 Regional Assessment Report for Rio+20: SE Asia Pacific (SEAP) Mountains Sustainable Mountain Development 1992, 2012 and Beyond Rio+20 Assessment Report for the Southeast Asia Pacific (SEAP) Region By: Ramon A. Razal Madhav Karki Benedicto Q. Sánchez Sanam Aksha Tek Jung Mahat Contributors: Ramon A. Razal – E-conference moderator; and Case Study writers: Delbert Rice (the Philippines); Mahuru, Rufus (Papua New Guinea); Le Buu Thach, Vu Ngoc Long, Le Van Huong, (Vietnam); and De Beer, Jenne (Indonesia) Editorial support: Binod Bhattarai International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) Kathmandu, Nepal & Non-Timber Forest Product-Exchange Programme for South and Southeast Manila, Philippines February 2012 1 Regional Assessment Report for Rio+20: SE Asia Pacific (SEAP) Mountains Acknowledgement and Disclaimer The Swiss Development Cooperation (SDC), a participant in the Mountain Partnership Consortium (MPC), provided financial support for undertaking the study. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect views of their organisations or that of the SDC. 2 Regional Assessment Report for Rio+20: SE Asia Pacific (SEAP) Mountains Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ....................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................