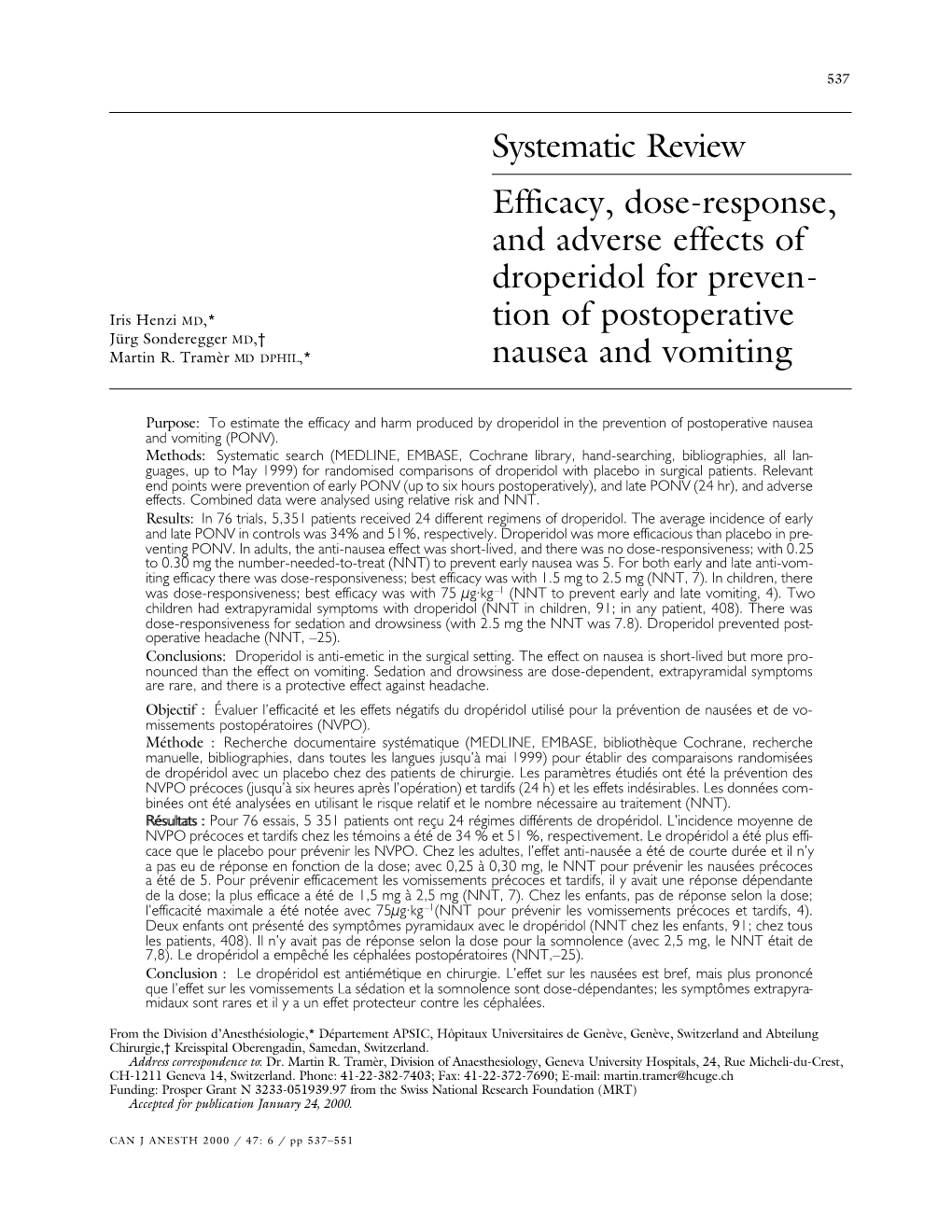

Efficacy, Dose-Response, and Adverse Effects of Droperidol for Prevention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domains: 1. Optimizing Medication Use, Using Front- and Back Office Strategies 2

A SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES Table S1: Domains and themes in the action plan of the Belgian Government (2015-2020) Domains: 1. Optimizing medication use, using front- and back office strategies 2. Continuity of pharmacotherapy in light of transmural care 3. Scientific skills of the hospital pharmacist 4. Transfer of information to and communication with the patient Themes: 2015: anchoring the minimal conditions for the application of clinical pharmacy 2016: development of a structured method for the anamnesis, registration and communication of the medication on admission and discharge 2017: application of clinical pharmacy for specific therapies 2018: application of risk screening for patient groups 2019: application of risk screening for medication groups or pathologies 2020: evaluation of the development of clinical pharmacy in the Belgian hospitals and evaluation of the action plan 2015-2020 Table S2: Anatomical and therapeutic classes of the drugs involved in the discrepancies detected after medication reconciliation n (%) Example(s) of discrepancy Gastro-intestinal system 43 (35.2%) antacids 6 O: antacid PRN antihistaminics 1 O: ranitidine 150 mg 1 pd proton pump inhibitors 5 O: pantoprazole 20 mg 1 pd propulsives 3 O: domperidone PRN; N: alizapride laxatives 9 O: macrogol PRN or 1 pd, bisacodyl PRN or 1 pd antipropulsives 2 O: loperamide 1 pd probiotics 1 O: frequent need for probiotics antidiabetics 1 D: dose repaglinide unknown multivitamins 5 O: multivitamins 1 pd vitamin D 5 O: vitamin D 1 per week vitamin B 2 N: vitamin B complex -

Drug Repurposing for the Management of Depression: Where Do We Stand Currently?

life Review Drug Repurposing for the Management of Depression: Where Do We Stand Currently? Hosna Mohammad Sadeghi 1,†, Ida Adeli 1,† , Taraneh Mousavi 1,2, Marzieh Daniali 1,2, Shekoufeh Nikfar 3,4,5 and Mohammad Abdollahi 1,2,* 1 Toxicology and Diseases Group (TDG), Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center (PSRC), The Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (TIPS), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran; [email protected] (H.M.S.); [email protected] (I.A.); [email protected] (T.M.); [email protected] (M.D.) 2 Department of Toxicology and Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran 3 Personalized Medicine Research Center, Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran; [email protected] 4 Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center (PSRC) and the Pharmaceutical Management and Economics Research Center (PMERC), Evidence-Based Evaluation of Cost-Effectiveness and Clinical Outcomes Group, The Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (TIPS), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran 5 Department of Pharmacoeconomics and Pharmaceutical Administration, School of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran * Correspondence: [email protected] † Equally contributed as first authors. Citation: Mohammad Sadeghi, H.; Abstract: A slow rate of new drug discovery and higher costs of new drug development attracted Adeli, I.; Mousavi, T.; Daniali, M.; the attention of scientists and physicians for the repurposing and repositioning of old medications. Nikfar, S.; Abdollahi, M. Drug Experimental studies and off-label use of drugs have helped drive data for further studies of ap- Repurposing for the Management of proving these medications. -

The Use of Stems in the Selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for Pharmaceutical Substances

WHO/PSM/QSM/2006.3 The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances 2006 Programme on International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Quality Assurance and Safety: Medicines Medicines Policy and Standards The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances FORMER DOCUMENT NUMBER: WHO/PHARM S/NOM 15 © World Health Organization 2006 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

Current Update in the Management of Post-Operative Neuraxial Opioid-Induced Pruritus Borja Mugabure Bujedo

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Current Update in the Management of Post-operative Neuraxial Opioid-induced Pruritus Borja Mugabure Bujedo Acute and Chronic Pain Unit, Department of Anesthesiology, Donostia University Hospital ABSTRACT Introduction: Itching is an extremely bothersome side effect that frequently appears after the epidural and intrathecal administration of opioids. This common side effect can be severe enough to be considered by the patient to be as bad or worse than the pain itself. Both prevention and treatments remain a challenge in the clinical management of these patients. Many drugs have been used to either treat or prevent the condition with variable results. Materials and Methods: This article’s purpose is to review the clinical literature and summarize the current evidence of efficacy and efficiency of pharmacological treatments available to manage opioid-induced pruritus mediated by spinal opioids in the post-operative setting. An analysis of how the mechanism of action of the most common drugs affects in their clinic usefulness is presented. This comprehensive review is limited to published papers in English, found on PubMed, Medline, and Scopus until December 2017. The papers used in this review were systematized reviews, randomized controlled trials, and opinion articles by subject experts. Results: The most useful drugs are mu opioid antagonists, such as naloxone, and mixed opioids kappa agonists/mu antagonists, such as nalbuphine and butorphanol, the latter being capable of maintaining analgesia in addition to reduce itching. Some efficacy has also been observed, to a lesser extent, from 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 serotonin receptor antagonists, such as prophylactically administered ondansetron, and D2 dopaminergic receptor antagonists, such as droperidol. -

Drug-Induced Pruritus: a Review

Acta Derm Venereol 2009; 89: 236–244 REVIEW ARTICLE Drug-induced Pruritus: A Review Adam REICH1, Sonja STÄNDER2 and Jacek C. SZepietowsKI1,3 1Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology, Wroclaw Medical University, 2Clinical Neurodermatology, Department of Dermatology, University Hospital of Münster, Germany, and 3Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy, Polish Academy of Sciences, Wroclaw, Poland Pruritus is an unpleasant sensation that leads to scrat- polate to drugs that are prescribed mainly in outpatient ching. In addition to several diseases, the administration clinics, as only inpatients were analysed. In another of drugs may induce pruritus. It is estimated that pru- study on skin reactions due to antibacterial agents used ritus accounts for approximately 5% of all skin adverse in 13,679 patients treated by general practitioners, reactions after drug intake. However, to date there has cutaneous adverse effects were reported in 135 (1%) been no systematic review of the natural course and pos- subjects, and general pruritus accounted for 13.3% of sible underlying mechanisms of drug-induced pruritus. these reactions (4). In a recent analysis of 200 patients For example, no clear distinction has been made between with drug reactions, 12.5% showed pruritus without acute or chronic (lasting more than 6 weeks) forms of skin lesions (5). However, only a few drugs have been pruritus. This review presents a systematic categoriza- analysed more carefully in relation to pruritus, mainly tion of the different forms of drug-induced pruritus, with antimalarials, opioids, and hydroxyethyl starch (see special emphasis on a therapeutic approach to this side- below). Furthermore, analysing the available data on effect. -

Stembook 2018.Pdf

The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances FORMER DOCUMENT NUMBER: WHO/PHARM S/NOM 15 WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2018.1 © World Health Organization 2018 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (WHO/EMP/RHT/TSN/2018.1). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. -

Microsoft Word

AUTORISES INTERDITS AC. ACETYLSALICYLIQUE AC. MEFENAMIQUE AC. CLAVULANIQUE AC. NALIDIXIQUE AC. FUSIDIQUE AC. PIPEMIDIQUE AC. NIFLUMIQUE AC. PIROMIDIQUE AC. OXOLINIQUE ACITRETINE AC. TIAPROFENIQUE ADRAFINIL AC. TIENILIQUE ALCOOL AC. TRANEXAMIQUE ALIZAPRIDE ACAMPROSATE ALLOPURINOL ACEBUTOLOL ALMINOPROFENE ACETAZOLAMIDE ALPRAZOLAM ACICLOVIR ALVERINE ACTH AMBROXOL ADRENALINE AMIDOPYRINE ALFENTANIL AMINEPTINE ALFUZOSINE AMINOGLUTHETIMIDE ALIMEMAZINE AMIODARONE AMANTADINE AMISULPRIDE AMFEPRAMONE AMOBARBITAL AMIKACINE ANDROGENES AMILORIDE ARTICAINE AMITRIPTYLINE ASTEMIZOLE AMLODIPINE BACLOFENE AMOXAPINE BARBITURIQUES AMOXICILLINE BENFLUOREX AMPHOTERICINE B BENZBROMARONE APTOCAINE BENZYL THIOURACILE ATENOLOL BEPRIDIL ATRACURIUM BETAHISTINE ATROPINE BIPERIDENE AZATHIOPRINE BISOPROLOL BENAZEPRIL BROMOCRIPTINE BENSERAZIDE BUPIVACAINE (*) BETA-ALANINE BUSPIRONE BETAXOLOL CAPTOPRIL BEZAFIBRATE CARBAMAZEPINE BLEOMYCINE CEFACLOR BROMAZEPAM CEFPODOXIME BROMURE CEFUROXIME BUFLOMEDIL CHLORAMPHENICOL BUPRENORPHINE CHLORMEZANONE BUTACAINE CHLOROQUINE (*) BUTYLHYOSCINE CIBENZOLINE CARBIMAZOLE CICLETANINE CARPIPRAMINE CIPROFIBRATE CEFIXIME CLINDAMYCINE CEFOTAXIME CLOBAZAM CEFTAZIDIME CLOFIBRATE CEFTRIAXONE CLOMETHIAZOLE CELIPROLOL CLOMIFENE CERIVASTATINE CLONIDINE CETIRIZINE CLORAZEPATE CHLORAL HYDRATE CLOTIAZEPAM CHLORDIAZEPOXIDE CYCLOPHOSPHAM 1 DE CHLORPROMAZINE CYPROTERONE CICLOSPORINE DANAZOL CILAZAPRIL DAPSONE CIMETIDINE DENORAL® CIPROFLOXACINE DEXFENFLURAMINE CISAPRIDE DEXTROMORAMIDE CITALOPRAM DEXTROPROPOXYPHENE CLARITHROMYCINE DIAZEPAM CLIDINIUM DIHYDRALAZINE -

Drugs/Medications Known to Cause Hyperhidrosis Certain Prescriptions

Drugs/Medications Known to Cause Hyperhidrosis Certain prescriptions and non-prescription medications can cause hyperhidrosis (excess perspiration or sweating) as a side effect. A list of potentially sweat-inducing medications is provided below. Medications are listed alphabetically by generic name. U.S. brand names are given in parentheses, if applicable. This list is provided as a resource and a service. It is not exhaustive and is in no way meant to replace consultation with a medical professional. Although sweating is a known side effect of the medications listed below, in most cases only a small percentage of people using the medicines experience undue sweating (in some cases less than 1%). Medications noted with an “*” and in bold are the most likely to cause sweating and the frequency of sweating as a side effect from these medications may be as high as 50%. Medications noted with an “†” are commonly-prescribed drugs; and those with a “P” are often used for pediatrics. Key: */Bold -- Known to commonly cause hyperhidrosis † -- Commonly-prescribed drugs P -- Pediatric use Abciximab (ReoPro®) Acamprosate (Campral®) Acetaminophen and Tramadol (Ultracet™) Acetophenazine (NA) Acetylcholine (Miochol-E®) P Acetylcysteine (Acetadote®) P Acitretin (Soriatane®) Acrivastine and Pseudoephedrine (Semprex®-D) † Acyclovir (Zovirax®) P Adenosine (Adenocard®; Adenoscan®) † Albuterol (Proventil® HFA Inhalation Aerosol) Alemtuzumab (Campath®) Alizapride (NA) Almotriptan (Axert™) Alosetron (Lotronex®) Amonafide (NA) Ambenonium (Mytelase®) Amitriptyline -

New Information of Dopaminergic Agents Based on Quantum Chemistry Calculations Guillermo Goode‑Romero1*, Ulrika Winnberg2, Laura Domínguez1, Ilich A

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN New information of dopaminergic agents based on quantum chemistry calculations Guillermo Goode‑Romero1*, Ulrika Winnberg2, Laura Domínguez1, Ilich A. Ibarra3, Rubicelia Vargas4, Elisabeth Winnberg5 & Ana Martínez6* Dopamine is an important neurotransmitter that plays a key role in a wide range of both locomotive and cognitive functions in humans. Disturbances on the dopaminergic system cause, among others, psychosis, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. Antipsychotics are drugs that interact primarily with the dopamine receptors and are thus important for the control of psychosis and related disorders. These drugs function as agonists or antagonists and are classifed as such in the literature. However, there is still much to learn about the underlying mechanism of action of these drugs. The goal of this investigation is to analyze the intrinsic chemical reactivity, more specifcally, the electron donor–acceptor capacity of 217 molecules used as dopaminergic substances, particularly focusing on drugs used to treat psychosis. We analyzed 86 molecules categorized as agonists and 131 molecules classifed as antagonists, applying Density Functional Theory calculations. Results show that most of the agonists are electron donors, as is dopamine, whereas most of the antagonists are electron acceptors. Therefore, a new characterization based on the electron transfer capacity is proposed in this study. This new classifcation can guide the clinical decision‑making process based on the physiopathological knowledge of the dopaminergic diseases. During the second half of the last century, a movement referred to as the third revolution in psychiatry emerged, directly related to the development of new antipsychotic drugs for the treatment of psychosis. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,560,544 B2 Webber Et Al

USOO756.0544B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,560,544 B2 Webber et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 14, 2009 (54) 3.5-DISUBSITITUTED AND 2003.01.00764 A1 5/2003 Bonket al. 3,5,7-TRISUBSTITUTED-3H-OXAZOLO AND 2003,01628.06 A1 8, 2003 Dellaria et al. 3H-THIAZOLO4,5-DIPYRIMIDIN-2-ONE 2003/0176458 A1 9, 2003 Dellaria et al. COMPOUNDS AND PRODRUGS THEREOF 2003/0186949 A1 10, 2003 Dellaria et al. 2003. O195209 A1 10, 2003 Dellaria et al. (75) Inventors: Stephen E. Webber, San Diego, CA S-8. A. 1929 St.oberts etet al. al. (US); Gregory J. Haley, Del Mar, CA 2005, 0004144 A1 1/2005 Carson et al. (US); Joseph R. Lennox, San Diego, CA (US); Alan X. Xiang, San Diego, CA FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (US); Erik J. Rueden, Santee, CA (US) EP O 882 727 9, 1998 EP 1 035 123 9, 2000 (73) Assignee: Anadys Pharmaceuticals, Inc., San EP 1043 021 10, 2000 Diego, CA (US) EP 1386,923 A1 2, 2004 WO WO-89/05649 6, 1989 Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this WO WO-92, 16215 10, 1992 (*) WO WO-94,07904 4f1994 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 WO WO-94, 17043 8, 1994 U.S.C. 154(b) by 119 days. WO WO-94.17090 8, 1994 WO WO-98, 17279 4f1998 (21) Appl. No.: 11/304,691 WO WO-03/045968 6, 2003 (22) Filed: Dec. 16, 2005 OTHER PUBLICATIONS Vippagunta et al. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 48 (2001)3-26.* (65) Prior Publication Data Lugemwaetal. -

Effectiveness of Alizapride for Prophylaxis of Nausea and Vomiting After Spinal Anesthesia for Cesarean Section

The Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine (October 2018) Vol. 73 (5), Page 6633-6640 Effectiveness of Alizapride for Prophylaxis of Nausea and Vomiting after Spinal Anesthesia for Cesarean Section Ayman Hussein Fahmy Kahla, Nasr Abdel-Aziz Mohammad Saad, Islam Mahmoud Mohamed Mahmoud Department of Anesthesia & Intensive Care, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University Corresponding author: Islam Mahmoud Mohamed Mahmoud, Mobile: 01099066287, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Background: Nausea and vomiting are common side effects in parturients undergoing cesarean delivery performed under spinal anesthesia can be very unpleasant to the patients. The reported incidence of nausea and vomiting during cesarean performed under regional anesthesia varies from 50% to 80% when no prophylactic antiemetic is given. Therefore, use of prophylactic antiemetics in parturients undergoing cesarean delivery is recommended by some authors. Objective: In this study, alizapride was evaluated, as a D2 receptor antagonist, on the prevention of nausea and vomiting following Spinal Anesthesia in parturients undergoing elective cesarean section. Patients and Methods: The study was carried out in AL-Azhar University Hospitals, Obstetric and gynaecology department on 90 patients undergoing an elective, lower segment cesarean section (LSCS). All patients were identified by code number to maintain the privacy of the patients. Any unexpected risks appeared during the course of the research was cleared to the participants and the ethical committee on time. A written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients were divided into 3 groups, 30 patients for each group. Group I (Alizapride 50 group): Received intravenous (IV) Alizapride 50 mg diluted in 10 ml of normal saline over 1-5 minutes, immediately after clamping umbilical cord. -

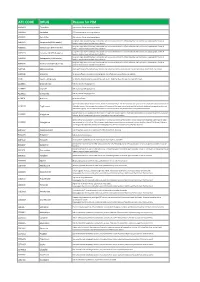

ATC CODE DRUG Reason for PIM

ATC CODE DRUG Reason for PIM A02BA01 Cimetidine CNS adverse effects including confusion A02BA02 Ranitidine CNS adverse effects including confusion A02BA03 Famotidine CNS adverse effects including confusion Long-term high dose PPI therapy is associated with an increased risk of C. difficile infection and hip fracture. Inappropriate if used >8 A02BC01 Omeprazole (PPI>8 weeks) weeks in maximal dose without clear indication Long-term high dose PPI therapy is associated with an increased risk of C. difficile infection and hip fracture. Inappropriate if used >8 A02BC02 Pantoprazole (PPI>8 weeks) weeks in maximal dose without clear indication Long-term high dose PPI therapy is associated with an increased risk of C. difficile infection and hip fracture. Inappropriate if used >8 A02BC03 Lansoprazole (PPI>8 weeks) weeks in maximal dose without clear indication Long-term high dose PPI therapy is associated with an increased risk of C. difficile infection and hip fracture. Inappropriate if used >8 A02BC04 Rabeprazole (PPI>8 weeks) weeks in maximal dose without clear indication Long-term high dose PPI therapy is associated with an increased risk of C. difficile infection and hip fracture. Inappropriate if used >8 A02BC05 Esomeprazole (PPI>8 weeks) weeks in maximal dose without clear indication A03FA01 Metoclopramide Antidopaminergic and anticholinergic effects; may worsen peripheral arterial blood flow and precipitate intermittent claudication A03FA05 Alizapride No proven efficacy; muscarinic-blocking agents; side effects such as confusion and sedation A10A Insulin, sliding scale No benefits demonstrated in using sliding-scale insulin. Might facilitate fluctuations in glycemic levels A10BB01 Glibenclamide Risk of protracted hypoglycemia A10BB07 Glipizide Risk of protracted hypoglycemia A10BB12 Glimepiride Risk of protracted hypoglycemia A10BF01 Acarbose No proven efficacy Age-related risks include bladder cancer, fractures and heart failure.