Representing Haiti by Amar Spencer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voting for Hope Elections in Haiti

COMMENTARY Voting for hope Elections in Haiti Peter Hallward ate in the night of 29 February 2004, after weeks of confusion and uncertainty, the enemies of Haitiʼs president Jean-Bertrand Aristide forced him into exile Lfor the second time. There was plenty of ground for confusion. Although twice elected with landslide majorities, by 2004 Aristide was routinely identified as an enemy of democracy. Although political violence declined dramatically during his years in office, he was just as regularly condemned as an enemy of human rights. Although he was prepared to make far-reaching compromises with his opponents, he was attacked as intolerant of dissent. Although still immensely popular among the poor, he was derided as aloof and corrupt. And although his enemies presented themselves as the friends of democracy, pluralism and civil society, the only way they could get rid of their nemesis was through foreign intervention and military force. Four times postponed, the election of Aristideʼs successor finally took place a few months ago, in February 2006. These elections were supposed to clear up the confusion of 2004 once and for all. With Aristide safely out of the picture, they were supposed to show how his violent and illegal expulsion had actually been a victory for democracy. With his Fanmi Lavalas party broken and divided, they were intended to give the true friends of pluralism and civil society that democratic mandate they had so long been denied. Haitiʼs career politicians, confined to the margins since Aristideʼs first election back in 1990, were finally to be given a chance to inherit their rightful place. -

Lavalas Organizer Imprisoned by the Occupation Government Since May 17, 2004

Rezistans Lyrics by Serge Madhere, Recorded by Sò Anne with Koral La They have made us know the way to jail Shut us in their concentration camps But we have not lost sight of our goal We are a people of resistance Slavery, occupation, nothing has broken us We have slipped through every trap We are a people of resistance Translated from kreyol © 2003 Annette Auguste (Sò Anne) Sò Anne is a Lavalas organizer imprisoned by the occupation government since May 17, 2004. She is one of more than 1,000 political prisoners who have been arrested since the coup. The vast majority have not been charged or tried. For more information about the campaign to free Sò Anne and all Haitian political prisoners, visit www.haitiaction.net. THE ACHIEVEMENTS OF LAVALAS IN HAITI We Will Not Forget THE ACHIEVEMENTS OF LAVALAS IN HAITI n February 29, 2004, the constitutional government of Haiti was overthrown, bringing Haiti’s ten-year experience with democracy to a brutal end. Orchestrated Oby the United States, France and Canada, the coup forced President Jean-Ber- trand Aristide into exile and removed thousands of elected officials from office. A year after the coup, the Haitian people continue to demand the restoration of democracy. On September 30, 2004, tens of thousands of Haitians took to the streets of Port-au-Prince. Braving police gunfire, threats of arrests and beatings, they marched while holding up their five fingers, signifying their determination that Aristide complete his five-year term. On December 1, 2004, while then-Secretary of State Colin Powell visited Haiti to express support for the coup regime, Haitian police massacred dozens of prisoners in the National Penitentiary who had staged a protest over prison conditions. -

The Election Impasse in Haiti

At a glance April 2016 The election impasse in Haiti The run-off in the 2015 presidential elections in Haiti has been suspended repeatedly, after the opposition contested the first round in October 2015. Just before the end of President Martelly´s mandate on 7 February 2016, an agreement was reached to appoint an interim President and a new Provisional Electoral Council, fixing new elections for 24 April 2016. Although most of the agreement has been respected , the second round was in the end not held on the scheduled date. Background After nearly two centuries of mainly authoritarian rule which culminated in the Duvalier family dictatorship (1957-1986), Haiti is still struggling to consolidate its own democratic institutions. A new Constitution was approved in 1987, amended in 2012, creating the conditions for a democratic government. The first truly free and fair elections were held in 1990, and won by Jean-Bertrand Aristide (Fanmi Lavalas). He was temporarily overthrown by the military in 1991, but thanks to international pressure, completed his term in office three years later. Aristide replaced the army with a civilian police force, and in 1996, when succeeded by René Préval (Inite/Unity Party), power was transferred democratically between two elected Haitian Presidents for the first time. Aristide was re-elected in 2001, but his government collapsed in 2004 and was replaced by an interim government. When new elections took place in 2006, Préval was elected President for a second term, Parliament was re-established, and a short period of democratic progress followed. A food crisis in 2008 generated violent protest, leading to the removal of the Prime Minister, and the situation worsened with the 2010 earthquake. -

Haiti's National Elections

Haiti’s National Elections: Issues and Concerns Maureen Taft-Morales Specialist in Latin American Affairs March 23, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41689 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Haiti’s National Elections: Issues and Concerns Summary In proximity to the United States, and with such a chronically unstable political environment and fragile economy, Haiti has been a constant policy issue for the United States. Congress views the stability of the nation with great concern and commitment to improving conditions there. Both Congress and the international community have invested significant resources in the political, economic, and social development of Haiti, and will be closely monitoring the election process as a prelude to the next steps in Haiti’s development. For the past 25 years, Haiti has been making the transition from a legacy of authoritarian rule to a democratic government. Elections are a part of that process. In the short term, elections have usually been a source of increased political tensions and instability in Haiti. In the long term, elected governments in Haiti have contributed to the gradual strengthening of government capacity and transparency. Haiti is currently approaching the end of its latest election cycle. Like many of the previous elections, the current process has been riddled with political tensions, allegations of irregularities, and violence. The first round of voting for president and the legislature was held on November 28, 2010. That vote was marred by opposition charges of fraud, reports of irregularities, and low voter turnout. When the electoral council’s preliminary results showed that out-going President Rene Préval’s little-known protégé, and governing party candidate, Jude Celestin, had edged out a popular musician for a spot in the runoff elections by less than one percent, three days of violent protests ensued. -

Won't Buy All Books

The Courier Volume 4 Issue 31 Article 1 6-4-1971 The Courier, Volume 4, Issue 31, June 4, 1971 Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.cod.edu/courier This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. First CD nursing Nearly 700 class graduates to graduate The fourth commencement College of DuPage will graduate Berg, college president, was the exercises of College of DuPage will its first class of nurses at next speaker. be Friday evening, June 11, at 7:45 week’s commencement exercises. Mrs. Santucci said she is urging in the college gym. About 650 Twenty eight nurses, one of them the students to work in general Associate degrees and about 50 male, will graduate and after hospitals for wide experience certificates in various technologies taking a state board examination before specializing. will be awarded. qualify as registered nurses. The class that was “pinned” Dr. Rodney Berg, college Mary Ann Santucci, chairman of includes: president, will introduce the stage the nursing program, presented Susan Altorfer, Carol Beechler, party and the speakers of the pins to the class at a meeting May Betty Black, Patricia Crandall, evening. Thomas Biggs, president 16 in the Gymnasium. Dr. Rodney Betty Crim, Donna Dorrough, of the Associated Student Body, Noreen Ehlenburg, Gloria Ellis, will make remarks. Phyllis Foster, Denise Gilman, The main speaker of the evening Diane Hastings, Carol Jenkins, will be Dr. -

Reconstructing Democracy

Reconstructing Democracy Joint Report of Independent Electoral Monitors of Haiti’s November 28, 2010 Election Let Haiti Live Organizations listed indicate participants in November 28th observer delegation Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Introduction II. Credibility and Timing of November 28, 2010 Election The CEP and Exclusions Without Justification Inadequate Time to Prepare Election Election in the Midst of Crises The Role of MINUSTAH III. Observations of the Independent Monitors IV. Responses from Haiti and the International Community Haitian Civil Society The OAS and CARICOM The United Nations The United States Canada V. Conclusions APPENDICES A. Additional Analysis of the Electoral Law B. Detailed Observation from the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti Team C. Summary of Election Day 11/28/10, The Louisiana Justice Institute, Jacmel D. Observations from Nicole Lazarre, The Louisiana Justice Institute, in Port-au-Prince E. Observations from Alexander Main, Center for Economic and Policy Research F. Observations from Clay Kilgore, Kledev G. Voices of Haiti: In Pursuit of the Undemocratic, Mark Snyder, International Action Ties H. U.S. Will Pay for Haitian Vote Fraud, Brian Concannon and Jeena Shah, IJDH Executive Summary The first round of Haiti’s presidential and legislative election was held on November 28, 2010 in particularly inauspicious conditions. Over one million people who lost their homes in the earthquake were still living in appalling conditions, in makeshift camps, in and around Port-au- Prince. A cholera epidemic that had already claimed over two thousand lives was raging throughout the country. Finally, the election was being organized by a provisional electoral authority council that was hand-picked by President Préval and widely distrusted. -

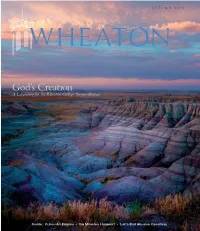

God's Creation and Learn More ABET Accredited Schools Including University of Illinois at Urbana- About Him

AUTUMN 2013 WHEATON God’s Creation A Laboratory for the Wheaton College Science Station Inside: Cuba––An Enigma • Do Miracles Happen? • Let’s End Abusive Coaching 133858_FC,IFC,01,BC.indd 1 8/4/13 4:31 PM Wheaton College serves Jesus Christ and advances His Kingdom through excellence in liberal arts and graduate programs that educate the whole person to build the church and benefit society worldwide. volume 16 issue 3 A u T umN 2013 6 14 ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 34 A Word with Alumni 2 Letters From the director of alumni relations 4 News 35 Wheaton Alumni Association News Sports Association news and events 10 56 Authors 40 Alumni Class News Books by Wheaton’s faculty; thoughts on grieving from Luke Veldt ’84. Cover photo: The Badlands of South Dakota is a destination for study and 58 Readings discovery for Wheaton students, and is in close proximity to their base Excerpts from the 2013 commencement address camp, the Wheaton College Science Station (see story, p.6). The geology by Rev. Francis Chan. program’s biannual field camp is a core academic requirement that gives majors experience in field methods as they participate in mapping 60 Faculty Voice exercises based on the local geological features of the Black Hills region. On field trips to the Badlands, environmental science and biology majors Dr. Michael Giuliano, head coach of men’s soccer learn about the arid grassland ecosystem and observe its unique plants and adjunct professor of communication studies, and animals. Geology students learn that the multicolored sediment layers calls for an end to abusive coaching. -

The Right to Vote – Haiti 2010/2010 Elections

2010/ 2011 The Right to Vote A Report Detailing the Haitian Elections for November 28, 2010 and March, 2011 “Voting is easy and marginally useful, but it is a poor substitute for democracy, which requires direct action by concerned citizens.” – Howard Zinn Human Rights Program The Right to Vote – Haiti 2010/2011 Elections Table of Contents Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Permanent vs. Provisional .......................................................................................................................... 2 Government in Shambles ............................................................................................................................ 2 November Elections .................................................................................................................................... 3 March Elections.......................................................................................................................................... 3 Laws Governing The Elections Process ......................................................................................................... 4 Constitution ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Electoral Law ............................................................................................................................................ -

Country Fact Sheet HAITI June 2007

National Documentation Packages, Issue Papers and Country Fact Sheets Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada www.irb-cisr.gc.ca ● Français ● Home ● Contact Us ● Help ● Search ● canada.gc.ca Home > Research > National Documentation Packages, Issue Papers and Country Fact Sheets Country Fact Sheet HAITI June 2007 Disclaimer 3. POLITICAL PARTIESF Front for Hope (Front de l’espoir, Fwon Lespwa): The Front for Hope was founded in 2005 to support the candidacy of René Préval in the 2006 presidential election.13 This is a party of alliances that include the Effort and Solidarity to Build a National and Popular Alternative (Effort de solidarité pour la construction d’une alternative nationale et populaire, ESCANP);14 the Open the Gate Party (Pati Louvri Baryè, PLB);15 and grass-roots organizations, such as Grand-Anse Resistance Committee Comité de résistance de Grand-Anse), the Central Plateau Peasants’ Group (Mouvement paysan du plateau Central) and the Southeast Kombit Movement (Mouvement Kombit du SudEst or Kombit Sudest).16 The Front for Hope is headed by René Préval,17 the current head of state, elected in 2006.18 In the 2006 legislative elections, the party won 13 of the 30 seats in the Senate and 24 of the 99 seats in the Chamber of Deputies.19 Merging of Haitian Social Democratic Parties (Parti Fusion des sociaux-démocrates haïtiens, PFSDH): This party was created on 23 April 2005 with the fusion of the following three democratic parties: Ayiti Capable (Ayiti kapab), the National Congress of Democratic Movements (Congrès national des -

Wheaton Athletes Worldwide

WH E A WHEATON T O N 21 INNOVATORS | COMMUNISM TO CHRIST | JIM HEIMBACH '78 | STUDENT DEBT REAR ADMIRAL R. TIMOTHY ZIEMER '68, P.46 USN (RET.) VOLUME 2015 ISSUE 18 3 // // AUTUMN 2015AUTUMN 21 Innovators in the 21st Century WHEATON.EDU/MAGAZINE Student Debt: Why It’s Worth It From Communism to Christ KNOW A STUDENT WHO BELONGS AT WHEATON? TELL US! As alumni and friends of Wheaton, you play a critical role in helping us identify the best and brightest students to recruit to the College. You have a unique understanding of Wheaton and can easily identify the type of students who will take full advantage of the Wheaton College experience. We value your opinion and invite you to join us in the recruit- ment process. Please send contact information of potential students you believe will thrive in Wheaton’s rigorous and Christ-centered academic environment. We will take the next step to connect with them and begin the process. 800.222.2419 x0 wheaton.edu/refer VOLUME 18 // ISSUE 3 AUTUMN 2015 featuresWHEATON “ I consider my work a success if I can provide a showcase of God’s creation with my creation.” ➝ Facebook facebook.com/ 21 INNOVATORS: ART: wheatoncollege.il LEADING THE JIM HEIMBACH ’78 WAY / 21 / 32 Twitter twitter.com/ wheatoncollege COMMENCEMENT: STUDENT DEBT: GOD’S DOUBLE WHY IT’S WORTH IT Instagram AGENT 30 34 instagram.com/ / / wheatoncollegeil WHEATON.EDU/MAGAZINE THE WHEATON FUND + YOU IT ALL ADDS UP TO A BIG DIFFERENCE households gave to 6,650 the Wheaton Fund 75 households gave $10,000 or more to the Wheaton Fund 635 households made a first-time Wheaton Fund gift 5 households gave $100,000 or more to the Wheaton Fund $814,614.85 given by those who gave less than $1,000 to the Wheaton Fund 58.55% of dollars came from alumni 26.57% of dollars came from parents 14.88% of dollars came from friends Numbers included here represent giving through June 10, 2015 Thank you for all you did to make fiscal year 2015 successful! Make your Wheaton Fund gift today to help get fiscal year 2016 off to a strong start. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 17 July 2000

United Nations A/55/154 General Assembly Distr.: General 17 July 2000 Original: English Fifty-fifth session Item 48 of the provisional agenda* The situation of democracy and human rights in Haiti / International Civilian Support Mission in Haiti Report of the Secretary-General** Contents Paragraphs Page I. Introduction 1 2 II. Political situation and elections 2-19 2 III. Deployment and operations of the International Civilian Support Mission in Haiti. 20-22 5 IV. Haitian National Police 23-26 5 V. Human rights 27-31 6 VI. Justice system 32-35 6 VII. Development activities 36-39 7 VIII. Observations 40-48 7 ' A/55/150. The footnote requested by the General Assembly in resolution 54/248 was not included in the submission. 00-54237 (E) 010800 A/55/154 I. Introduction 4. Concern about the repeated postponements was raised by the Group of Friends of the Secretary- 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to General for Haiti and other envoys in several meetings General Assembly resolution 54/193 of 17 December with President Pre"val and Prime Minister Alexis. I 1999, in which the General Assembly established the wrote to President Pr6val on 15 March 2000 to reiterate International Civilian Support Mission in Haiti the Organization's continuing support for the efforts of (MICAH) in order to consolidate the results achieved the Haitian people and Government to consolidate by the Organization of American States (OAS)/United democracy, establish the rule of law and create Nations International Civilian Mission in Haiti conditions propitious to socio-economic development. (MIC1VIH), the United Nations Civilian Police On that occasion, I stated that the prompt holding of Mission in Haiti (MIPONUH) and previous United free, transparent and credible elections was an essential Nations missions. -

70 Candidats Inscrits Pour Les Élections/Sélections !

Vol. 8 • No. 46 • Du 27 mai au 2 juin 2015 Haiti 20 gdes/ USA $1.50/ France 2 euros/ Canada $2.00 JUSTICEHAÏTI • VÉRITÉ • INDÉPENDANCE LIBERTÉ Nou sonje jeneral 1583 Albany Ave, Brooklyn, NY 11210 Tel: 718-421-0162 Email: [email protected] Web: www.haitiliberte.com Benwa Batravil ! 70 CANDIDATS INSCRITS POUR LES Page 4 ÉLECTIONS/SÉLECTIONS ! English Page 9 Les élections annoncées riment- t-elles avec l’insécurité ? Assassinat d’Emmanuel Goutier Page 7 Voir page 8 Ci-dessus de gauche à droite: Supplice Beauzile Edmonde, Moise Jean Charles et ci-dessous Jovenel Moise et Gautier Marie Antoinette LAURENT LAMOTHE S’AUDITE LUI-MÊME! Damnés de la mer, damnés du capitalisme : Réflexion sur le phénomène Lampedusa ! Page 12 Barcelone, épicentre du Voir page 5 changement Conférence de presse de Laurent Salvador Lamothe, le mardi 26 mai, à la salle Thérèse de l’hôtel Le Plaza, pour contester le rapport de la Cour Page 18 supérieure des comptes et du contentieux administratif et se donner lui-même un audit favorable à son administration Editorial HAITI LIBERTÉ 1583 Albany Ave Brooklyn, NY 11210 Tel: 718-421-0162 Fax: 718-421-3471 Fruits vénéneux de la division et perspectives 3, 2ème Impasse Lavaud Port-au-Prince, Haiti Par Berthony Dupont oublier « le capitalisme est un péché mortel ». Fort de cette cohé- sion, le peuple n’avait pas permis qu’on bloquât ou manipulât Email : [email protected] les élections de 1990. Cette opération avait bouleversé les plans e pays est en train de voler en éclats du fait d’une crise élec- machiavéliques de certaines ambassades occidentales en Haïti Website : Ltorale reflétant une large paralysie, elle-même engendrant au point que bien avant les élections, nous étions sûrs de les www.haitiliberte.com une situation sociale fortement agitée.