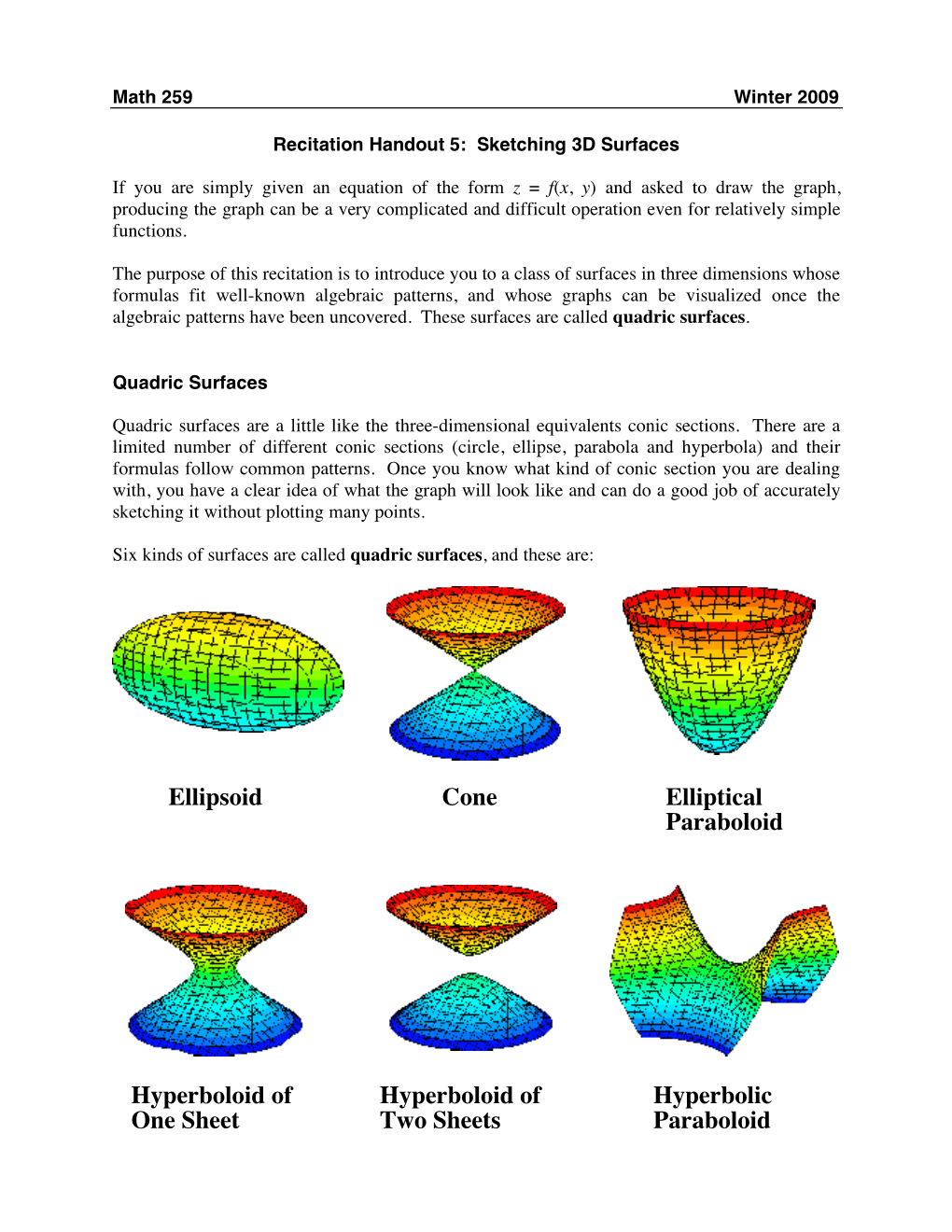

Ellipsoid Cone Elliptical Paraboloid Hyperboloid of One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quadratic Approximation at a Stationary Point Let F(X, Y) Be a Given

Multivariable Calculus Grinshpan Quadratic approximation at a stationary point Let f(x; y) be a given function and let (x0; y0) be a point in its domain. Under proper differentiability conditions one has f(x; y) = f(x0; y0) + fx(x0; y0)(x − x0) + fy(x0; y0)(y − y0) 1 2 1 2 + 2 fxx(x0; y0)(x − x0) + fxy(x0; y0)(x − x0)(y − y0) + 2 fyy(x0; y0)(y − y0) + higher−order terms: Let (x0; y0) be a stationary (critical) point of f: fx(x0; y0) = fy(x0; y0) = 0. Then 2 2 f(x; y) = f(x0; y0) + A(x − x0) + 2B(x − x0)(y − y0) + C(y − y0) + higher−order terms, 1 1 1 1 where A = 2 fxx(x0; y0);B = 2 fxy(x0; y0) = 2 fyx(x0; y0), and C = 2 fyy(x0; y0). Assume for simplicity that (x0; y0) = (0; 0) and f(0; 0) = 0. [ This can always be achieved by translation: f~(x; y) = f(x0 + x; y0 + y) − f(x0; y0). ] Then f(x; y) = Ax2 + 2Bxy + Cy2 + higher−order terms. Thus, provided A, B, C are not all zero, the graph of f near (0; 0) resembles the quadric surface z = Ax2 + 2Bxy + Cy2: Generically, this quadric surface is either an elliptic or a hyperbolic paraboloid. We distinguish three scenarios: * Elliptic paraboloid opening up, (0; 0) is a point of local minimum. * Elliptic paraboloid opening down, (0; 0) is a point of local maximum. * Hyperbolic paraboloid, (0; 0) is a saddle point. It should certainly be possible to tell which case we are dealing with by looking at the coefficients A, B, and C, and this is the idea behind the Second Partials Test. -

Chapter 11. Three Dimensional Analytic Geometry and Vectors

Chapter 11. Three dimensional analytic geometry and vectors. Section 11.5 Quadric surfaces. Curves in R2 : x2 y2 ellipse + =1 a2 b2 x2 y2 hyperbola − =1 a2 b2 parabola y = ax2 or x = by2 A quadric surface is the graph of a second degree equation in three variables. The most general such equation is Ax2 + By2 + Cz2 + Dxy + Exz + F yz + Gx + Hy + Iz + J =0, where A, B, C, ..., J are constants. By translation and rotation the equation can be brought into one of two standard forms Ax2 + By2 + Cz2 + J =0 or Ax2 + By2 + Iz =0 In order to sketch the graph of a quadric surface, it is useful to determine the curves of intersection of the surface with planes parallel to the coordinate planes. These curves are called traces of the surface. Ellipsoids The quadric surface with equation x2 y2 z2 + + =1 a2 b2 c2 is called an ellipsoid because all of its traces are ellipses. 2 1 x y 3 2 1 z ±1 ±2 ±3 ±1 ±2 The six intercepts of the ellipsoid are (±a, 0, 0), (0, ±b, 0), and (0, 0, ±c) and the ellipsoid lies in the box |x| ≤ a, |y| ≤ b, |z| ≤ c Since the ellipsoid involves only even powers of x, y, and z, the ellipsoid is symmetric with respect to each coordinate plane. Example 1. Find the traces of the surface 4x2 +9y2 + 36z2 = 36 1 in the planes x = k, y = k, and z = k. Identify the surface and sketch it. Hyperboloids Hyperboloid of one sheet. The quadric surface with equations x2 y2 z2 1. -

Pencils of Quadrics

Europ. J. Combinatorics (1988) 9, 255-270 Intersections in Projective Space II: Pencils of Quadrics A. A. BRUEN AND J. w. P. HIRSCHFELD A complete classification is given of pencils of quadrics in projective space of three dimensions over a finite field, where each pencil contains at least one non-singular quadric and where the base curve is not absolutely irreducible. This leads to interesting configurations in the space such as partitions by elliptic quadrics and by lines. 1. INTRODUCTION A pencil of quadrics in PG(3, q) is non-singular if it contains at least one non-singular quadric. The base of a pencil is a quartic curve and is reducible if over some extension of GF(q) it splits into more than one component: four lines, two lines and a conic, two conics, or a line and a twisted cubic. In order to contain no points or to contain some line over GF(q), the base is necessarily reducible. In the main part of this paper a classification is given of non-singular pencils ofquadrics in L = PG(3, q) with a reducible base. This leads to geometrically interesting configur ations obtained from elliptic and hyperbolic quadrics, such as spreads and partitions of L. The remaining part of the paper deals with the case when the base is not reducible and is therefore a rational or elliptic quartic. The number of points in the elliptic case is then governed by the Hasse formula. However, we are able to derive an interesting combi natorial relationship, valid also in higher dimensions, between the number of points in the base curve and the number in the base curve of a dual pencil. -

Radar Back-Scattering from Non-Spherical Scatterers

REPORT OF INVESTIGATION NO. 28 STATE OF ILLINOIS WILLIAM G. STRATION, Governor DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION VERA M. BINKS, Director RADAR BACK-SCATTERING FROM NON-SPHERICAL SCATTERERS PART 1 CROSS-SECTIONS OF CONDUCTING PROLATES AND SPHEROIDAL FUNCTIONS PART 11 CROSS-SECTIONS FROM NON-SPHERICAL RAINDROPS BY Prem N. Mathur and Eugam A. Mueller STATE WATER SURVEY DIVISION A. M. BUSWELL, Chief URBANA. ILLINOIS (Printed by authority of State of Illinois} REPORT OF INVESTIGATION NO. 28 1955 STATE OF ILLINOIS WILLIAM G. STRATTON, Governor DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION VERA M. BINKS, Director RADAR BACK-SCATTERING FROM NON-SPHERICAL SCATTERERS PART 1 CROSS-SECTIONS OF CONDUCTING PROLATES AND SPHEROIDAL FUNCTIONS PART 11 CROSS-SECTIONS FROM NON-SPHERICAL RAINDROPS BY Prem N. Mathur and Eugene A. Mueller STATE WATER SURVEY DIVISION A. M. BUSWELL, Chief URBANA, ILLINOIS (Printed by authority of State of Illinois) Definitions of Terms Part I semi minor axis of spheroid semi major axis of spheroid wavelength of incident field = a measure of size of particle prolate spheroidal coordinates = eccentricity of ellipse = angular spheroidal functions = Legendse polynomials = expansion coefficients = radial spheroidal functions = spherical Bessel functions = electric field vector = magnetic field vector = back scattering cross section = geometric back scattering cross section Part II = semi minor axis of spheroid = semi major axis of spheroid = Poynting vector = measure of size of spheroid = wavelength of the radiation = back scattering -

John Ellipsoid 5.1 John Ellipsoid

CSE 599: Interplay between Convex Optimization and Geometry Winter 2018 Lecture 5: John Ellipsoid Lecturer: Yin Tat Lee Disclaimer: Please tell me any mistake you noticed. The algorithm at the end is unpublished. Feel free to contact me for collaboration. 5.1 John Ellipsoid In the last lecture, we discussed that any convex set is very close to anp ellipsoid in probabilistic sense. More precisely, after renormalization by covariance matrix, we have kxk2 = n ± Θ(1) with high probability. In this lecture, we will talk about how convex set is close to an ellipsoid in a strict sense. If the convex set is isotropic, it is close to a sphere as follows: Theorem 5.1.1. Let K be a convex body in Rn in isotropic position. Then, rn + 1 B ⊆ K ⊆ pn(n + 1)B : n n n Roughly speaking, this says that any convex set can be approximated by an ellipsoid by a n factor. This result has a lot of applications. Although the bound is tight, making a body isotropic is pretty time- consuming. In fact, making a body isotropic is the current bottleneck for obtaining faster algorithm for sampling in convex sets. Currently, it can only be done in O∗(n4) membership oracle plus O∗(n5) total time. Problem 5.1.2. Find a faster algorithm to approximate the covariance matrix of a convex set. In this lecture, we consider another popular position of a convex set called John position and its correspond- ing ellipsoid is called John ellipsoid. Definition 5.1.3. Given a convex set K. -

Calculus & Analytic Geometry

TQS 126 Spring 2008 Quinn Calculus & Analytic Geometry III Quadratic Equations in 3-D Match each function to its graph 1. 9x2 + 36y2 +4z2 = 36 2. 4x2 +9y2 4z2 =0 − 3. 36x2 +9y2 4z2 = 36 − 4. 4x2 9y2 4z2 = 36 − − 5. 9x2 +4y2 6z =0 − 6. 9x2 4y2 6z =0 − − 7. 4x2 + y2 +4z2 4y 4z +36=0 − − 8. 4x2 + y2 +4z2 4y 4z 36=0 − − − cone • ellipsoid • elliptic paraboloid • hyperbolic paraboloid • hyperboloid of one sheet • hyperboloid of two sheets 24 TQS 126 Spring 2008 Quinn Calculus & Analytic Geometry III Parametric Equations (§10.1) and Vector Functions (§13.1) Definition. If x and y are given as continuous function x = f(t) y = g(t) over an interval of t-values, then the set of points (x, y)=(f(t),g(t)) defined by these equation is a parametric curve (sometimes called aplane curve). The equations are parametric equations for the curve. Often we think of parametric curves as describing the movement of a particle in a plane over time. Examples. x = 2cos t x = et 0 t π 1 t e y = 3sin t ≤ ≤ y = ln t ≤ ≤ Can we find parameterizations of known curves? the line segment circle x2 + y2 =1 from (1, 3) to (5, 1) Why restrict ourselves to only moving through planes? Why not space? And why not use our nifty vector notation? 25 Definition. If x, y, and z are given as continuous functions x = f(t) y = g(t) z = h(t) over an interval of t-values, then the set of points (x,y,z)= (f(t),g(t), h(t)) defined by these equation is a parametric curve (sometimes called a space curve). -

A Brief Tour of Vector Calculus

A BRIEF TOUR OF VECTOR CALCULUS A. HAVENS Contents 0 Prelude ii 1 Directional Derivatives, the Gradient and the Del Operator 1 1.1 Conceptual Review: Directional Derivatives and the Gradient........... 1 1.2 The Gradient as a Vector Field............................ 5 1.3 The Gradient Flow and Critical Points ....................... 10 1.4 The Del Operator and the Gradient in Other Coordinates*............ 17 1.5 Problems........................................ 21 2 Vector Fields in Low Dimensions 26 2 3 2.1 General Vector Fields in Domains of R and R . 26 2.2 Flows and Integral Curves .............................. 31 2.3 Conservative Vector Fields and Potentials...................... 32 2.4 Vector Fields from Frames*.............................. 37 2.5 Divergence, Curl, Jacobians, and the Laplacian................... 41 2.6 Parametrized Surfaces and Coordinate Vector Fields*............... 48 2.7 Tangent Vectors, Normal Vectors, and Orientations*................ 52 2.8 Problems........................................ 58 3 Line Integrals 66 3.1 Defining Scalar Line Integrals............................. 66 3.2 Line Integrals in Vector Fields ............................ 75 3.3 Work in a Force Field................................. 78 3.4 The Fundamental Theorem of Line Integrals .................... 79 3.5 Motion in Conservative Force Fields Conserves Energy .............. 81 3.6 Path Independence and Corollaries of the Fundamental Theorem......... 82 3.7 Green's Theorem.................................... 84 3.8 Problems........................................ 89 4 Surface Integrals, Flux, and Fundamental Theorems 93 4.1 Surface Integrals of Scalar Fields........................... 93 4.2 Flux........................................... 96 4.3 The Gradient, Divergence, and Curl Operators Via Limits* . 103 4.4 The Stokes-Kelvin Theorem..............................108 4.5 The Divergence Theorem ...............................112 4.6 Problems........................................114 List of Figures 117 i 11/14/19 Multivariate Calculus: Vector Calculus Havens 0. -

Introduction to Aberrations OPTI 518 Lecture 13

Introduction to aberrations OPTI 518 Lecture 13 Prof. Jose Sasian OPTI 518 Topics • Aspheric surfaces • Stop shifting • Field curve concept Prof. Jose Sasian OPTI 518 Aspheric Surfaces • Meaning not spherical • Conic surfaces: Sphere, prolate ellipsoid, hyperboloid, paraboloid, oblate ellipsoid or spheroid • Cartesian Ovals • Polynomial surfaces • Infinite possibilities for an aspheric surface • Ray tracing for quadric surfaces uses closed formulas; for other surfaces iterative algorithms are used Prof. Jose Sasian OPTI 518 Aspheric surfaces The concept of the sag of a surface 2 cS 4 6 8 10 ZS ASASASAS4 6 8 10 ... 1 1 K ( c2 1 ) 2 S Sxy222 K 2 K is the conic constant K=0, sphere K=-1, parabola C is 1/r where r is the radius of curvature; K is the K<-1, hyperola conic constant (the eccentricity squared); -1<K<0, prolate ellipsoid A’s are aspheric coefficients K>0, oblate ellipsoid Prof. Jose Sasian OPTI 518 Conic surfaces focal properties • Focal points for Ellipsoid case mirrors Hyperboloid case Oblate ellipsoid • Focal points of lenses K n2 Hecht-Zajac Optics Prof. Jose Sasian OPTI 518 Refraction at a spherical surface Aspheric surface description 2 cS 4 6 8 10 ZS ASASASAS4 6 8 10 ... 1 1 K ( c2 1 ) 2 S 1122 2222 22 y x Aicrasphe y 1 x 4 K y Zx 28rr Prof. Jose Sasian OTI 518P Cartesian Ovals ln l'n' Cte . Prof. Jose Sasian OPTI 518 Aspheric cap Aspheric surface The aspheric surface can be thought of as comprising a base sphere and an aspheric cap Cap Spherical base surface Prof. -

Geodetic Position Computations

GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E. J. KRAKIWSKY D. B. THOMSON February 1974 TECHNICALLECTURE NOTES REPORT NO.NO. 21739 PREFACE In order to make our extensive series of lecture notes more readily available, we have scanned the old master copies and produced electronic versions in Portable Document Format. The quality of the images varies depending on the quality of the originals. The images have not been converted to searchable text. GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E.J. Krakiwsky D.B. Thomson Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering University of New Brunswick P.O. Box 4400 Fredericton. N .B. Canada E3B5A3 February 197 4 Latest Reprinting December 1995 PREFACE The purpose of these notes is to give the theory and use of some methods of computing the geodetic positions of points on a reference ellipsoid and on the terrain. Justification for the first three sections o{ these lecture notes, which are concerned with the classical problem of "cCDputation of geodetic positions on the surface of an ellipsoid" is not easy to come by. It can onl.y be stated that the attempt has been to produce a self contained package , cont8.i.ning the complete development of same representative methods that exist in the literature. The last section is an introduction to three dimensional computation methods , and is offered as an alternative to the classical approach. Several problems, and their respective solutions, are presented. The approach t~en herein is to perform complete derivations, thus stqing awrq f'rcm the practice of giving a list of for11111lae to use in the solution of' a problem. -

Structural Forms 1

Key principles The hyperboloid of revolution is a Surface and may be generated by revolving a Hyperbola about its conjugate axis. The outline of the elevation will be a Hyperbola. When the conjugate axis is vertical all horizontal sections are circles. The horizontal section at the mid point of the conjugate axis is known as the Throat. The diagram shows the incomplete construction for drawing a hyperbola in a rectangle. (a) Draw the outline of the both branches of the double hyperbola in the rectangle. The diagram shows the incomplete Elevation of a hyperboloid of revolution. (a) Determine the position of the throat circle in elevation. (b) Draw the outline of the both branches of the double hyperbola in elevation. DESIGN & COMMUNICATION GRAPHICS Structural forms 1 NAME: ______________________________ DATE: _____________ The diagram shows the plan and incomplete elevation of an object based on the hyperboloid of revolution. The focal points and transverse axis of the hyperbola are also shown. (a) Using the given information draw the outline of the elevation.. F The diagram shows the axis, focal points and transverse axis of a double hyperbola. (a) Draw the outline of both branches of the double hyperbola. (b) The difference between the focal distances for any point on a double hyperbola is constant and equal to the length of the transverse axis. (c) Indicate this principle on the drawing below. DESIGN & COMMUNICATION GRAPHICS Structural forms 2 NAME: ______________________________ DATE: _____________ Key principles The diagram shows the plan and incomplete elevation of a hyperboloid of revolution. The hyperboloid of revolution may also be generated by revolving one skew line about another. -

Models for Earth and Maps

Earth Models and Maps James R. Clynch, Naval Postgraduate School, 2002 I. Earth Models Maps are just a model of the world, or a small part of it. This is true if the model is a globe of the entire world, a paper chart of a harbor or a digital database of streets in San Francisco. A model of the earth is needed to convert measurements made on the curved earth to maps or databases. Each model has advantages and disadvantages. Each is usually in error at some level of accuracy. Some of these error are due to the nature of the model, not the measurements used to make the model. Three are three common models of the earth, the spherical (or globe) model, the ellipsoidal model, and the real earth model. The spherical model is the form encountered in elementary discussions. It is quite good for some approximations. The world is approximately a sphere. The sphere is the shape that minimizes the potential energy of the gravitational attraction of all the little mass elements for each other. The direction of gravity is toward the center of the earth. This is how we define down. It is the direction that a string takes when a weight is at one end - that is a plumb bob. A spirit level will define the horizontal which is perpendicular to up-down. The ellipsoidal model is a better representation of the earth because the earth rotates. This generates other forces on the mass elements and distorts the shape. The minimum energy form is now an ellipse rotated about the polar axis. -

Quadric Surfaces

Quadric Surfaces SUGGESTED REFERENCE MATERIAL: As you work through the problems listed below, you should reference Chapter 11.7 of the rec- ommended textbook (or the equivalent chapter in your alternative textbook/online resource) and your lecture notes. EXPECTED SKILLS: • Be able to compute & traces of quadic surfaces; in particular, be able to recognize the resulting conic sections in the given plane. • Given an equation for a quadric surface, be able to recognize the type of surface (and, in particular, its graph). PRACTICE PROBLEMS: For problems 1-9, use traces to identify and sketch the given surface in 3-space. 1. 4x2 + y2 + z2 = 4 Ellipsoid 1 2. −x2 − y2 + z2 = 1 Hyperboloid of 2 Sheets 3. 4x2 + 9y2 − 36z2 = 36 Hyperboloid of 1 Sheet 4. z = 4x2 + y2 Elliptic Paraboloid 2 5. z2 = x2 + y2 Circular Double Cone 6. x2 + y2 − z2 = 1 Hyperboloid of 1 Sheet 7. z = 4 − x2 − y2 Circular Paraboloid 3 8. 3x2 + 4y2 + 6z2 = 12 Ellipsoid 9. −4x2 − 9y2 + 36z2 = 36 Hyperboloid of 2 Sheets 10. Identify each of the following surfaces. (a) 16x2 + 4y2 + 4z2 − 64x + 8y + 16z = 0 After completing the square, we can rewrite the equation as: 16(x − 2)2 + 4(y + 1)2 + 4(z + 2)2 = 84 This is an ellipsoid which has been shifted. Specifically, it is now centered at (2; −1; −2). (b) −4x2 + y2 + 16z2 − 8x + 10y + 32z = 0 4 After completing the square, we can rewrite the equation as: −4(x − 1)2 + (y + 5)2 + 16(z + 1)2 = 37 This is a hyperboloid of 1 sheet which has been shifted.