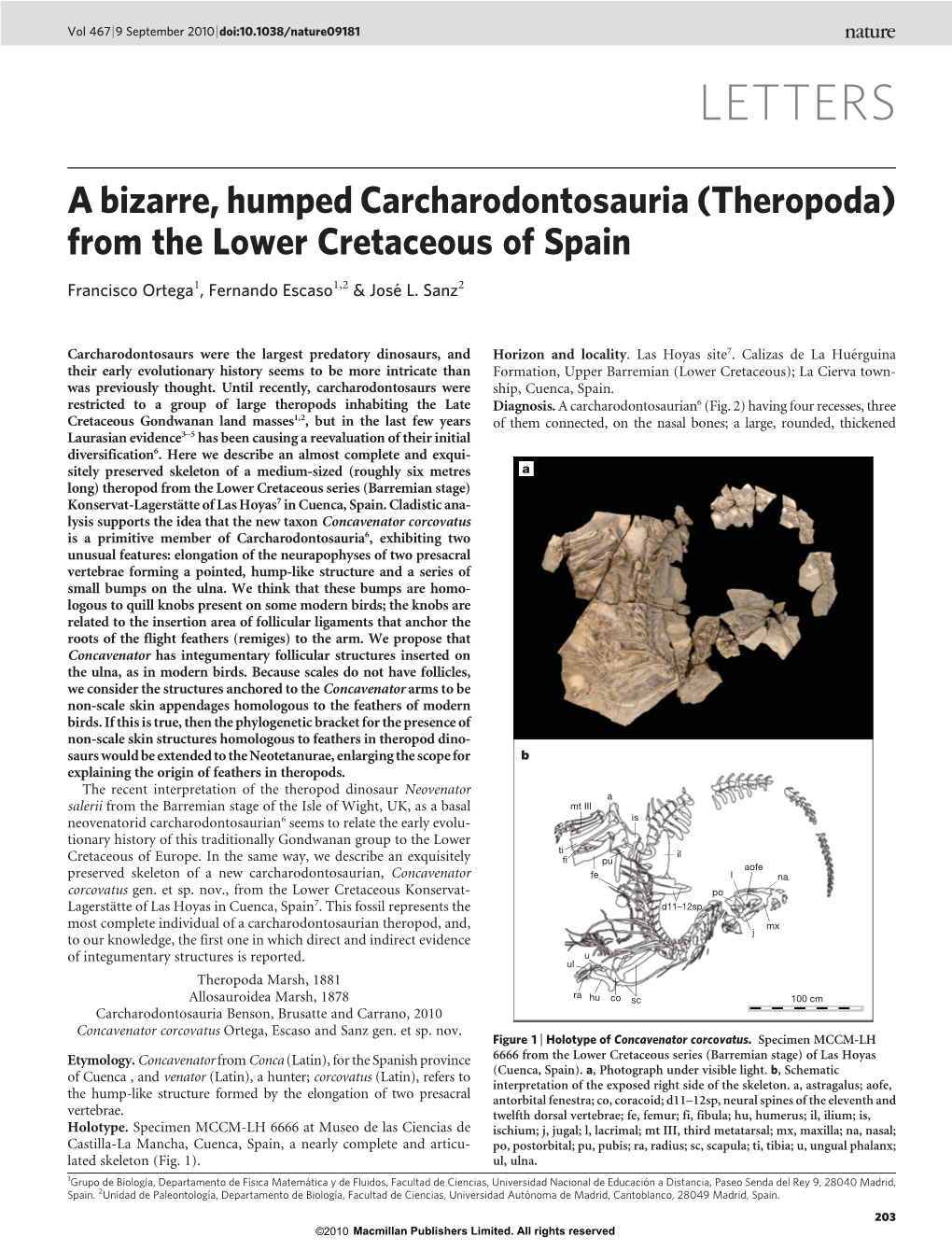

(Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evidence of a New Carcharodontosaurid from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco

http://app.pan.pl/SOM/app57-Cau_etal_SOM.pdf SUPPLEMENTARY ONLINE MATERIAL FOR Evidence of a new carcharodontosaurid from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco Andrea Cau, Fabio Marco Dalla Vecchia, and Matteo Fabbri Published in Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 2012 57 (3): 661-665. http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2011.0043 SOM1. PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS Material and Methods The data set of the phylogenetic analysis includes 37 Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) (35 ingroup neotheropod taxa, including one based on MPM 2594; and two basal theropod outgroups, Herrerasaurus and Tawa), and 808 character statements (see S2 and S3, below). The phylogenetic analyses were conducted through PAUP* vers. 4.010b (Swofford 2002). In the analysis, Herrerasaurus was used as root of the tree. The tree search strategy follows Benson (2009). The analysis initially performed a preliminary search using PAUPRat (Sikes and Lewis 2001). The unique topologies among the most parsimonious trees (MPTs) resulted after the preliminary search were used as a starting point for 1000 tree-bisection-reconnection branch swapping heuristic searches using PAUP*. Included taxa (and source for codings) Outgroup Herrerasaurus (Sereno 1993; Sereno and Novas 1993; Novas 1994; Sereno 2007) Tawa (Nesbitt et al. 2009) Ingroup Abelisaurus (Bonaparte and Novas 1985; Carrano and Sampson 2008) Acrocanthosaurus (Stoval and Landston 1950; Harris 1998; Currie and Carpenter 2000; Eddy and Clarke 2011) Allosaurus (Gilmore 1920; Madsen 1976) Baryonyx (Charig and Milner 1997; Mateus et al. 2010) Carcharodontosaurus (Stromer 1931; Sereno et al. 1996; Brusatte and Sereno 2007) Carnotaurus (Bonaparte et al. 1990) Ceratosaurus (Gilmore 1920; Madsen and Welles 2000). Compsognathus (Peyer 2006) Cryolophosaurus (Smith et al. -

D Inosaur Paleobiology

Topics in Paleobiology The study of dinosaurs has been experiencing a remarkable renaissance over the past few decades. Scientifi c understanding of dinosaur anatomy, biology, and evolution has advanced to such a degree that paleontologists often know more about 100-million-year-old dinosaurs than many species of living organisms. This book provides a contemporary review of dinosaur science intended for students, researchers, and dinosaur enthusiasts. It reviews the latest knowledge on dinosaur anatomy and phylogeny, Brusatte how dinosaurs functioned as living animals, and the grand narrative of dinosaur evolution across the Mesozoic. A particular focus is on the fossil evidence and explicit methods that allow paleontologists to study dinosaurs in rigorous detail. Scientifi c knowledge of dinosaur biology and evolution is shifting fast, Dinosaur and this book aims to summarize current understanding of dinosaur science in a technical, but accessible, style, supplemented with vivid photographs and illustrations. Paleobiology Dinosaur The Topics in Paleobiology Series is published in collaboration with the Palaeontological Association, Paleobiology and is edited by Professor Mike Benton, University of Bristol. Stephen Brusatte is a vertebrate paleontologist and PhD student at Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History. His research focuses on the anatomy, systematics, and evolution of fossil vertebrates, especially theropod dinosaurs. He is particularly interested in the origin of major groups such Stephen L. Brusatte as dinosaurs, birds, and mammals. Steve is the author of over 40 research papers and three books, and his work has been profi led in The New York Times, on BBC Television and NPR, and in many other press outlets. -

Late Jurassic Theropod Dinosaur Bones from the Langenberg Quarry

Late Jurassic theropod dinosaur bones from the Langenberg Quarry (Lower Saxony, Germany) provide evidence for several theropod lineages in the central European archipelago Serjoscha W. Evers1 and Oliver Wings2 1 Department of Geosciences, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland 2 Zentralmagazin Naturwissenschaftlicher Sammlungen, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Halle (Saale), Germany ABSTRACT Marine limestones and marls in the Langenberg Quarry provide unique insights into a Late Jurassic island ecosystem in central Europe. The beds yield a varied assemblage of terrestrial vertebrates including extremely rare bones of theropod from theropod dinosaurs, which we describe here for the first time. All of the theropod bones belong to relatively small individuals but represent a wide taxonomic range. The material comprises an allosauroid small pedal ungual and pedal phalanx, a ceratosaurian anterior chevron, a left fibula of a megalosauroid, and a distal caudal vertebra of a tetanuran. Additionally, a small pedal phalanx III-1 and the proximal part of a small right fibula can be assigned to indeterminate theropods. The ontogenetic stages of the material are currently unknown, although the assignment of some of the bones to juvenile individuals is plausible. The finds confirm the presence of several taxa of theropod dinosaurs in the archipelago and add to our growing understanding of theropod diversity and evolution during the Late Jurassic of Europe. Submitted 13 November 2019 Accepted 19 December 2019 Subjects Paleontology, -

Biology of the Rabbit

Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science Vol 45, No 1 Copyright 2006 January 2006 by the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science Pages 8–24 Historical Special Topic Overview on Rabbit Comparative Biology Biology of the Rabbit Nathan R. Brewer Editor’s note: In recognition of Dr. Nathan Brewer’s many years of dedicated service to AALAS and the community of research animal care specialists, the premier issue of JAALAS includes the following compilation of Dr. Brewer’s essays on rabbit anatomy and physiology. These essays were originally published in the ASLAP newsletter (formerly called Synapse), and are reprinted here with the permission and endorsement of that organization. I would like to thank Nina Hahn, Jane Lacher, and Nancy Austin for assistance in compiling these essays. Publishing this information in JAALAS allows Dr. Brewer’s work to become part of the searchable literature for laboratory animal science and medicine and also assures that the literature references and information he compiled will not be lost to posterity. However, readers should note that this material has undergone only minor editing for style, has not been edited for content, and, most importantly, has not undergone peer review. With the agreement of the associate editors and the AALAS leadership, I elected to forego peer review of this work, in contradiction to standard JAALAS policy, based on the status of this material as pre-published information from an affiliate organization that holds the copyright and on the esteem in which we hold for Dr. Brewer as a founding father of our organization. -

Evaluating the Ecology of Spinosaurus: Shoreline Generalist Or Aquatic Pursuit Specialist?

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Evaluating the ecology of Spinosaurus: Shoreline generalist or aquatic pursuit specialist? David W.E. Hone and Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. ABSTRACT The giant theropod Spinosaurus was an unusual animal and highly derived in many ways, and interpretations of its ecology remain controversial. Recent papers have added considerable knowledge of the anatomy of the genus with the discovery of a new and much more complete specimen, but this has also brought new and dramatic interpretations of its ecology as a highly specialised semi-aquatic animal that actively pursued aquatic prey. Here we assess the arguments about the functional morphology of this animal and the available data on its ecology and possible habits in the light of these new finds. We conclude that based on the available data, the degree of adapta- tions for aquatic life are questionable, other interpretations for the tail fin and other fea- tures are supported (e.g., socio-sexual signalling), and the pursuit predation hypothesis for Spinosaurus as a “highly specialized aquatic predator” is not supported. In contrast, a ‘wading’ model for an animal that predominantly fished from shorelines or within shallow waters is not contradicted by any line of evidence and is well supported. Spinosaurus almost certainly fed primarily from the water and may have swum, but there is no evidence that it was a specialised aquatic pursuit predator. David W.E. Hone. Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London, E1 4NS, UK. [email protected] Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742 USA and Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20560 USA. -

Dinosaurs British Isles

DINOSAURS of the BRITISH ISLES Dean R. Lomax & Nobumichi Tamura Foreword by Dr Paul M. Barrett (Natural History Museum, London) Skeletal reconstructions by Scott Hartman, Jaime A. Headden & Gregory S. Paul Life and scene reconstructions by Nobumichi Tamura & James McKay CONTENTS Foreword by Dr Paul M. Barrett.............................................................................10 Foreword by the authors........................................................................................11 Acknowledgements................................................................................................12 Museum and institutional abbreviations...............................................................13 Introduction: An age-old interest..........................................................................16 What is a dinosaur?................................................................................................18 The question of birds and the ‘extinction’ of the dinosaurs..................................25 The age of dinosaurs..............................................................................................30 Taxonomy: The naming of species.......................................................................34 Dinosaur classification...........................................................................................37 Saurischian dinosaurs............................................................................................39 Theropoda............................................................................................................39 -

Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in Later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2020-0174.R1 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 04-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Holtz, Thomas; University of Maryland at College Park, Department of Geology; NationalDraft Museum of Natural History, Department of Geology Keyword: Dinosaur, Ontogeny, Theropod, Paleocology, Mesozoic, Tyrannosauridae Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special Tribute to Dale Russell Issue? : © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 91 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: 2 Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous 3 Asiamerica 4 5 6 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 7 8 Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA 9 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20013 USA 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 ORCID: 0000-0002-2906-4900 Draft 12 13 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 14 Department of Geology 15 8000 Regents Drive 16 University of Maryland 17 College Park, MD 20742 18 USA 19 Phone: 1-301-405-4084 20 Fax: 1-301-314-9661 21 Email address: [email protected] 22 23 1 © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 91 24 ABSTRACT 25 Well-sampled dinosaur communities from the Jurassic through the early Late Cretaceous show 26 greater taxonomic diversity among larger (>50kg) theropod taxa than communities of the 27 Campano-Maastrichtian, particularly to those of eastern/central Asia and Laramidia. -

Theropoda: Spinosauridae) from the Middle Cretaceous of Morocco and Implications for Spinosaur Ecology

Cretaceous Research 93 (2019) 129e142 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Cretaceous Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/CretRes Juvenile spinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) from the middle Cretaceous of Morocco and implications for spinosaur ecology * Rebecca J. Lakin , Nicholas R. Longrich Department of Biology and Biochemistry, Milner Centre for Evolution, University of Bath, Bath, BA2 7AY, UK article info abstract Article history: The Spinosauridae is a specialised clade of theropod dinosaurs known from the Berriasian to the Cen- Received 29 May 2018 omanian of Africa, South America, Europe and Asia. Spinosaurs were unusual among non-avian di- Received in revised form nosaurs in exploiting a piscivorous niche within riverine and estuarine habitats, and they include the 24 August 2018 largest known theropod. Although fossils of giant spinosaurs are increasingly well-represented in the Accepted in revised form 18 September fossil record, little juvenile material has been described. Here, we describe new examples of juvenile 2018 Available online 19 September 2018 spinosaurines from the middle Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Kem Kem beds of Morocco. The fossils include material from a range of sizes and are relatively common within the Kem Kem deposits, suggesting that Keywords: juveniles exploited the same semiaquatic niche as the adults throughout ontogeny. This implies that the Dinosauria Cenomanian delta habitats supported an age-inclusive population of spinosaurs that was neither Spinosauridae geographically or environmentally separated, though some ecological separation between juveniles and Juvenile adults is likely based on the large variation in size. Bones or teeth of very small (<2 m) spinosaurs have Ontogeny not been found, however. This could represent a taphonomic bias, or potentially an ecological signal that Cretaceous the earliest ontogenetic stages inhabited distinct environments. -

Characters of American Jurassic Dinosaurs. Part VIII. the Order Theropoda

328 Scientific Intelligence. selves in the first spiral coil of 0. tenuissima are what constitute the essential difference between the spire of Cornuspira and that of Spirolocidina; marking an imperfect septal division of the spire into chambers, which cannot be conceived to affect in any way the physiological condition of. the contained animal, but which foreshadows the complete septal division that marks the assumption of the Peneropline stage. Again, the incipient widen- ing-out of the body, previously to the formation of the first complete septum, prepares the way for that great lateral exten sion which characterizes the next or Orbiculine stage ; this exten sion being obviously related, on the one hand, to the division of the chamber-segments of the body into chamberletted sub-seg ments, and, on the other, to the extension of the zonal chambers round the ' nucleus,' so as to complete them into aunuli, from APPENDIX. which all subsequent increase shall take place on the cyclical plan. "In 0. marginalia, the first spiral stage is abbreviated by the drawing-together (as it were) of the ' spiroloculine' coil into a single Milioline turn of greater thickness ; but the Orbiculine or second spiral stage is fully retained. In Q. duplex, the abbreviated. Milioline center is still retained, but the succeeding Orbiculine ART. X X X VI-I I. — Prmcvpal Characters of American spiral is almost entirely dropped out, quickly giving place to the Jurassic Dinosaurs ', by Professor 0. 0. MAESH. Part cyclical plan. And in the typical 0. complanctta the Milioline center is immediately surrounded by a complete annulus, so YIII. -

Index of Subjects

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47594-5 — Dinosaurs 4th Edition Index More Information INDEX OF SUBJECTS – – – A Zuul, 275 276 Barrett, Paul, 98, 335 336, 406, 446 447 Ankylosauridae Barrick, R, 383–384 acetabulum, 71, 487 characteristics of, 271–273 basal dinosauromorph, 101 acromial process, 271, 273, 487 cladogram of, 281 basal Iguanodontia, 337 actual diversity, 398 defined, 488 basal Ornithopoda, 336 adenosine diphosphate, see ADP evolution of, 279 Bates, K. T., 236, 360 adenosine triphosphate, see ATP ankylosaurids, 275–276 beak, 489 ADP (adenosine diphosphate), 390, 487 anpsids, 76 belief systems, 474, 489 advanced characters, 55, 487 antediluvian period, 422, 488 Bell, P. R., 162 aerobic metabolism, 391, 487 anterior position, 488 bennettitaleans, 403, 489 – age determination (dinosaur), 354 357 antorbital fenestra, 80, 488 benthic organisms, 464, 489 Age of Dinosaurs, 204, 404–405 Arbour, Victoria, 277 Benton, M. J., 2, 104, 144, 395, 402–403, akinetic movement, see kinetic movement Archibald, J. D., 467, 469 444–445, 477–478 Alexander, R. M., 361 Archosauria, 80, 88–90, 203, 488 Berman, D. S, 236–237 allometry, 351, 487 Archosauromorpha, 79–81, 488 Beurien, Karl, 435 altricial offspring, 230, 487 archosauromorphs, 401 bidirectional respiration, 350 Alvarez, Luis, 455 archosaurs, 203, 401 Big Al, 142 – Alvarez, Walter, 442, 454 455, 481 artifacts, 395 biogeography, 313, 489 Alvarezsauridae, 487 Asaro, Frank, 455 biomass, 415, 489 – alvarezsaurs, 168 169 ascending process of the astragalus, 488 biosphere, 2 alveolus/alveoli, -

Our Museum Dinosaurs

Our Museum Dinosaurs Coelophysis Tyrannosaurus Means: ‘hollow form’ Means: ‘tyrant lizard’ Say it: seel-oh-FIE-sis Say it: tie-ran-oh-SORE-us Where found: USA Where found: USA, Canada Type: Theropod Type: Theropod Length: 3m Length: 12m Height: 2m Height: 3.6m Weight: 27kg Weight: 8,300kg How it moved: walked on two legs, may have run How it moved: swiftly on two legs Teeth: 60 saw-edged, bone-crushing, pointed Teeth: small and sharp teeth in immensely strong jaws Type of feeder: CARNIVORE Type of feeder: CARNIVORE + SCAVENGER Food: small reptiles and insects Food: all other animals When it lived: 225-220 million years ago When it lived: 68-66 million years ago In the museum In the museum Models of Coelophysis Full size replica of its skull REAL fossil footprints Polacanthus Edmontosaurus Means: ‘many prickles’ Means: ‘Edmonton lizard’ Say it: pole-a-CAN-thus Say it: ed-mon-toe-SORE-us Where found: England Where found: North America Type: Ankylosaur Type: Hadrosaur Length: 5m Length: 13m Height: 1m Height: 3.5m Weight: 2 tonnes Weight: 3,400kg How it moved: walked on four legs How it moved: on two or four legs Teeth: small Teeth: horny beak, 200 grinding cheek teeth Type of feeder: HERBIVORE Type of feeder: HERBIVORE Food: plants Food: pine needles, seeds, twigs and leaves When it lived: 130-125 million years ago When it lived: 73-66 million years ago In the museum In the museum Partial skeleton of A REAL Edmontosaurus skeleton Polacanthus (in rock) Fossil Edmontosaurus skin imprint Hypsilophodon Dracoraptor Means: ‘high-crested tooth’ Means: ‘dragon robber’ Say it: hip-sih-LOW-foh-don Say it: DRAY-co-RAP-tor Where found: Isle of Wight, England Where found: Wales Type: Ornithiscian (orn-i-thi-SHE-an) Type: Theropod Length: around 3m Length: 1.8m Height: around 1m Height: 0.8m (80cm) Weight: around 25kg Weight: 20kg How it moved: walked or ran on two legs How it moved: swiftly on two legs Teeth: small pointed serrated teeth Teeth: horny beak, c. -

Cranial Anatomy of Allosaurus Jimmadseni, a New Species from the Lower Part of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Western North America

Cranial anatomy of Allosaurus jimmadseni, a new species from the lower part of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Western North America Daniel J. Chure1,2,* and Mark A. Loewen3,4,* 1 Dinosaur National Monument (retired), Jensen, UT, USA 2 Independent Researcher, Jensen, UT, USA 3 Natural History Museum of Utah, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA 4 Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Allosaurus is one of the best known theropod dinosaurs from the Jurassic and a crucial taxon in phylogenetic analyses. On the basis of an in-depth, firsthand study of the bulk of Allosaurus specimens housed in North American institutions, we describe here a new theropod dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Western North America, Allosaurus jimmadseni sp. nov., based upon a remarkably complete articulated skeleton and skull and a second specimen with an articulated skull and associated skeleton. The present study also assigns several other specimens to this new species, Allosaurus jimmadseni, which is characterized by a number of autapomorphies present on the dermal skull roof and additional characters present in the postcrania. In particular, whereas the ventral margin of the jugal of Allosaurus fragilis has pronounced sigmoidal convexity, the ventral margin is virtually straight in Allosaurus jimmadseni. The paired nasals of Allosaurus jimmadseni possess bilateral, blade-like crests along the lateral margin, forming a pronounced nasolacrimal crest that is absent in Allosaurus fragilis. Submitted 20 July 2018 Accepted 31 August 2019 Subjects Paleontology, Taxonomy Published 24 January 2020 Keywords Allosaurus, Allosaurus jimmadseni, Dinosaur, Theropod, Morrison Formation, Jurassic, Corresponding author Cranial anatomy Mark A.