Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPAA Vol. 8 No. 4 Warschauer: Technology and School Reform Di

Education Policy Analysis Archives Volume 8 Number 4 January 7, 2000 ISSN 1068-2341 A peer-reviewed scholarly electronic journal Editor: Gene V Glass, College of Education Arizona State University Copyright 2000, the EDUCATION POLICY ANALYSIS ARCHIVES . Permission is hereby granted to copy any article if EPAA is credited and copies are not sold. Articles appearing in EPAA are abstracted in the Current Index to Journals in Education by the ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation and are permanently archived in Resources in Education . Technology and School Reform: A View from Both Sides of the Tracks Mark Warschauer America-Mideast Educational & Training Services Cairo, Egypt Abstract A discourse of reform claims that schools must be transformed to take full advantage of computers, while a competing discourse of inequality warns that technology-enhanced reform is taking place only in wealthy schools, dooming poor and minority students to the wrong side of a digital divide. A qualitative study at an elite private school and an impoverished public school explored the relationship between technology, reform, and equality. The reforms introduced at the two schools appeared similar, but underlying differences in resources and expectations served to reinforce patterns by which the two schools channel students into different social futures. As educators cope with the task of integrating information technology into the schools, two main discourses have appeared: the discourse of reform and the discourse of inequality. The discourse of reform suggests that schools must transform themselves in order to make effective use of computers. As an educator in Hawai'i (Note 1) commented, The analogy that I have to give is that there is television and there is radio 1 of 22 and there is in person. -

Qt9hx124s9 Nosplash 083D343

PAPER UNDER REVIEW: PLEASE DO NOT DISTRIBUTE OR USE RESULTS WITHOUT THE EXPRESSED PERMISSION OF THE LEAD AUTHOR: MARK WARSCHAUER [email protected] Broadening our Concepts of Universal Access Mark Warschauer Professor of Education & Informatics Associate Dean, School of Education University of California, Irvine School of Education 3200 Education Irvine, CA 92697-5500 Email: [email protected] and Veronica Ahumada Newhart Graduate Student Researcher University of California, Irvine School of Education 3200 Education Irvine, CA 92697-5500 Email: [email protected] Abstract: The universal accessibility movement has focused on solutions for people with physical limitations. While this work has helped bring about positive initiatives for this population, physical disabilities are just one of the many life situations that can complicate people’s ability to fully participate in an information economy and society. Other factors affecting accessibility include poverty, illiteracy, and social isolation. This paper explores how the universal accessibility movement can expand its efforts to reach other diverse populations. We discuss four sets of resources -- physical, digital, human, and social -- that are critical for enabling people to use information and communication technology, and provide some examples of how these resources can help people access, adapt, and create knowledge. Keywords: universal access; accessibility; communication; education 1 PAPER UNDER REVIEW: PLEASE DO NOT DISTRIBUTE OR USE RESULTS WITHOUT THE EXPRESSED PERMISSION OF THE LEAD AUTHOR: MARK WARSCHAUER [email protected] Introduction As Manuel Castells (1998) notes, the ability to access, use, and adapt information and communication technologies is “the critical factor in generating and accessing wealth, power, and knowledge in our time” (p. -

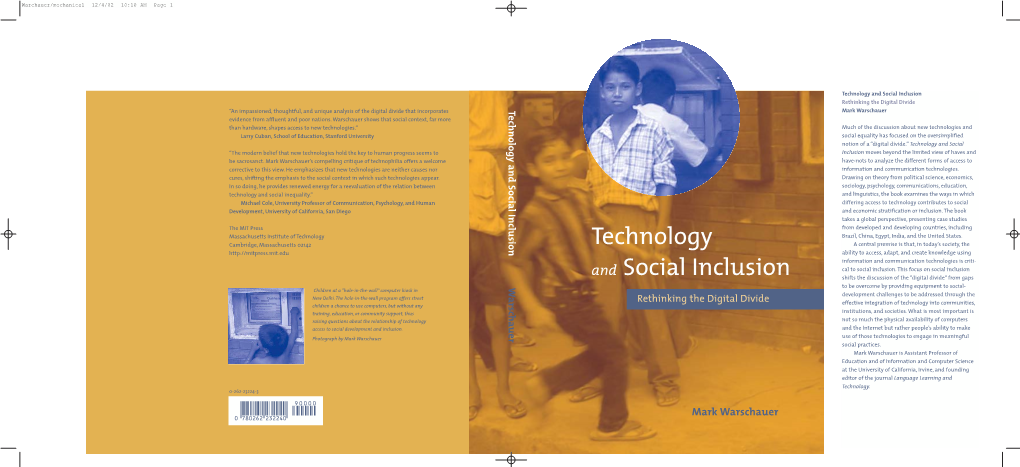

117 Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide. By

Reviews 117 Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide. By Mark Warschauer. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003. 274 pp. ISBN 0262232243. Mark Warschauer provides a wide-ranging, provocative re-evaluation of the “digital divide,” which he prefers to describe as a complex, multi-layered “digital inequality.” His point of view and sympathies clearly bridge the two academic disciplines with which he is most closely associated—education and computer science—in which he has a cross appointment at the University of California, Irvine. Citing fascinating examples from his own and other international research, he points out that despite some well-laid plans for access to information and communication technology (ICT), much remains to be done to ensure that technological and information “literacy” are also guaranteed. Poorly designed implementation programs are largely to blame for digital inequality, as Warschauer points out in examples from Ireland (where in one case, more—not less— social disenfranchisement was encountered by unemployed, isolated ICT users after they stopped going to the unemployment office and instead used ICT at home to look for work); from India (where no instruction was provided after ICT was placed in public areas); and from Egypt (where a USAID project was so mishandled that computer hardware sat in storage for more than a year before anything tangible got under way). In what has become a remarkably effective political-economic method of evaluating technology adoption and diffusion, Warschauer refers to three “industrial revolutions” (in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries) that have had huge impacts on society, the economy, and the further development of technology. -

Demystifying the Digital Divide Author(S): Mark Warschauer Source: Scientific American, Vol

Demystifying the Digital Divide Author(s): Mark Warschauer Source: Scientific American, Vol. 289, No. 2 (AUGUST 2003), pp. 42-47 Published by: Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26060401 Accessed: 05-06-2018 13:38 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26060401?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Scientific American This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Tue, 05 Jun 2018 13:38:29 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms By Mark Warschauer Demystifying Digitalthe Divide The simple binary notion of technology haves and have-nots doesn’t quite compute For much of the past decade, policy leaders and social scientists have grown increasingly concerned about a so- cietal split between those with and those without access to computers and the In- ternet. The U.S. National Telecommuni- cations and Information Ad- ministration popularized a term for this situation in the mid-1990s: the “digital di- vide.” The phrase soon became used in an international context as well, to describe the status of information technology from country to country. -

From Telecollaboration to Virtual Exchange: State-Of-The‑Art and the Role of Unicollaboration in Moving Forward1

From telecollaboration to virtual exchange: state-of-the-art and the role of UNICollaboration in moving forward1 Robert O’Dowd2 Abstract elecollaboration, or ‘virtual exchange’, are terms used to refer to the engagement of groups of learners in online intercultural interactions and collaboration projects with partners from other cultural contexts or geographical locations as an integrated Tpart of their educational programmes. In recent years, approaches to virtual exchange have evolved in different contexts and different areas of education, and these approaches have had, at times, very diverse organisational structures and pedagogical objectives. This article provides an overview of the different models and approaches to virtual exchange which are currently being used in higher education contexts. It also provides a short historical review of the major developments and trends in virtual exchange to date and describes the origins of the UNICollaboration organisation and the rationale behind this journal. Keywords: virtual exchange; telecollaboration; online intercultural exchange; computer mediated communication; intercultural communication; internationalisation. 1. Parts of this article were previously published in an article by the same author (O’Dowd, 2017) which appeared in the TLC Journal - Training Language & Culture, 4(2). They have been reproduced with permission. 2. University of León, León, Spain; [email protected] Robert O’Dowd has published widely on the application of collaborative online learning in university education. His most recent publication is the co-edited volume Online Intercultural Exchange Policy, Pedagogy, Practice, for Routledge. He is currently the lead researcher on the Erasmus+ KA3 project, Evaluating and Upscaling Telecollaborative Teacher Education (EVALUATE) (http://www.evaluateproject.eu/). -

Plenary Speeches/Invited Papers, Conferences in 2009

英語教學 English Teaching & Learning 34. 1 (Spring 2010): 147-166 Plenary Speeches/Invited Papers, Conferences in 2009 2009 American Association for Applied Linguistics (AAAL) Conference Time: March 6-9, 2009 Place: Denver, Colorado Theme: The Relevance of Applied Linguistics to the Real World and to Other Fields of Scientific Inquiry Keynote Speeches: (1) Lyle Bachman University of California, Los Angeles, US Toward an 'Activist' Applied Linguistics (2) Ellen Bialystok York University, Toronto, Canada Interactions of Language Processing and Cognitive Control in Bilingualism (3) Guy Cook The Open University, UK Sweet Talking: Food, Language, and Democracy (4) Graham Crookes University of Hawai'i, US The Relevance of SL Critical Pedagogy (5) Rod Ellis University of Auckland, New Zealand Second Language Acquisition: Theory, Research and Language Pedagogy 英語教學 English Teaching & Learning 34.1 (Spring 2010) (6) Heidi Hamilton Georgetown University, US Life as a Linguist Among Clinicians: Learnings from Cross-disciplinary Collaborations 2009 International Conference and Workshop on TEFL and Applied Linguistics Time: : March 13-14, 2009 Place: Ming Chuan University, Taiwan Theme: Teacher Empowerment and Language Acquisition in EFL Contexts Plenary Speeches: (1) Brian Huot Kent State University, US Reconsidering Assessment for the Teaching and Learning of Writing (2) Stephen Krashen University of South California, US Anything but (3) Sandra J. Savignon Penn State University, US The Quest for Communicative Competence: Theory and Classroom Practice -

Dissecting the “Digital Divide”: a Case Study in Egypt

The Information Society, 19: 297–304, 2003 Copyright c Taylor & Francis Inc. ISSN: 0197-2243 print / 1087-6537 online DOI: 10.1080/01972240390227877 Dissecting the “Digital Divide”: A Case Study in Egypt Mark Warschauer Department of Education, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, California, USA tion (NGO) download information for her. The notion of a For the last decade, the concept of a “digital divide” has framed binary divide is thus inaccurate and can be patronizing, as it people’s understanding of technology’s relationship to equity and fails to value the social resources that diverse groups bring development. This article critiques theoretically the digital divide to the table. For example, in the United States, African- concept and supports this critique by examining a case study of Americans are often portrayed as being on the wrong end technology and education in Egypt. The study illustrates the social of a digital divide (e.g., Walton, 1999), when in fact In- embeddedness of technology and the intertwining of computer ac- ternet access among Blacks and other minorities varies cess with broader issues of political power, thus refuting simplistic tremendously by income group, with divisions between notions of divides to be overcome through provision of equipment. Blacks and Whites decreasing as income increases (Na- tional Telecommunications and Information Administra- Keywords digital divide, education, Egypt, international tion, 2000). Second, and even more significantly, the stratification that does exist regarding access to online information has very little to do with the Internet per se, but has everything Since first emerging nearly a decade ago, the concept of to do with political, economic, institutional, cultural, and a “digital divide” has captured the attention of policy mak- linguistic contexts that shape the meaning of the Internet ers and social activities. -

English Teaching Forum Magazine January 2002, Volume 40, Number 4

02-0246 ETF_02-09 12/6/02 8:48 AM Page 2 William P. Ancker UNITED STATES TheChallenge Opportunityand of echnology: ANTINTERVIEW WITH MARK WARSCHAUER MARK WARSCHAUER IS VICE CHAIR OF THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AT THE University of California, Irvine and a faculty associate at the university’s Center for Research on Information Technology and Organizations. He has previously taught and conducted research at the University of California (Berkeley), the University of Hawaii, Moscow Linguistics University, and Charles University (Prague). Dr. Warschauer’s research focuses on the role of information and communication technologies (ICT) in second/foreign language learning and teaching; the impact of ICT on literacy; and the relationship of ICT to institutional reform, democracy, and social development. He is the founding editor of the journal Language Learning & Technology and editor of the Papyrus News email list. This interview was conducted by the editor-in-chief of the Forum on April 9, 2002 at the international TESOL convention held in Salt Lake City, Utah. 2 O CTOBER 2002 E NGLISH T EACHING F ORUM 02-0246 ETF_02-09 12/6/02 8:48 AM Page 3 WPA: Can you tell us how your career in second/foreign lan- net but not necessarily on the World Wide Web. Now, of guage teaching began? course, with Hotmail and Yahoo Mail, many people are MW: After I graduated from college, I traveled in Mexico doing email and chatting on the Web and that’s why there’s and Central America and learned some Spanish. My first confusion between the two. Technically, the Internet is the job when I came back was as a Spanish bilingual teacher broader communications protocol that allows people to aide in an elementary school in San Francisco helping stu- connect to the World Wide Web, and the Web is a just a dents with math and English. -

Designing Effective Education Programs Using Information and Communication Technology (ICT)

First Principles: Designing Effective Education Programs Using Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Compendium Credit: American Institutes for Research This First Principles: Designing Effective Education Programs Using Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Compendium provides important overview guidance for designing and implementing education programs that use technology. The principles and indicators are primarily meant to guide program designs, including the development of requests for and subsequent review of proposals, the implementation of program activities, and the development of performance management plans, evaluations, and research studies. The First Principles are intended to help USAID education officers specifically, as well as other stakeholders—including staff in donor agencies, government officials, and staff working for international and national non-governmental organizations—take advantage of good practices and lessons learned to improve projects that involve the use of education technology. The guidance in this document is meant to be used and adapted for a variety of settings to help USAID officers and others grapple with the multiple dimensions of ICT in education and overcome the numerous challenges in applying ICT in the developing-country contexts. The last section provides references for those who would like to learn more about issues and methods for supporting the education of the underserved. This document is based on extensive experience in, and investigation of, current approaches to technology in education and draws on research literature, interviews with USAID field personnel, and project documentation. It also includes profiles of projects funded by USAID and others. ThisCompendium provides greater depth for those who are interested in knowing more on this topic. A shorter companion piece called a Digest provides a brief overview of key considerations in the planning and implementation of education technology projects. -

Teachers' Experiences with Transnational,Telecollaborative

This book provides a nexus between research and practice through teachers’ narratives of their experiences with telecollaboration. The book begins with Melinda Dooly & a chapter outlining the pedagogical and theoretical underpinnings of telecol- laboration (also known as Virtual Exchange), followed by eight chapters that Robert O’Dowd (eds) explain telecollaborative project design, materials and activities as well as frank discussions of obstacles met and resolved during the project imple- mentation. The projects described in the volume serve as excellent examples for any teacher or education stakeholder interested in setting up their own In This Together: telecollaborative exchange. Teachers’ Experiences with Transnational, Telecollaborative Language Learning Projects In This Together: Teachers’ Experiences with Transnational, Experiences with Transnational, Teachers’ In This Together: elecollaborative Language Learning Projects TELECOLLABORATION IN EDUCATION 6 Melinda Dooly & Robert O’Dowd (eds) PETER LANG www.peterlang.com ISBN 978-3-0343-3501-0 Melinda Ann Dooly Owenby and Robert O'Dowd - 978-3-0343-3534-8 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/11/2019 02:35:37AM via free access PETER LANG TE_006 433501_Dooly_TL 155x225Br globalL.indd 1 13.06.18 16:30 This book provides a nexus between research and practice through teachers’ narratives of their experiences with telecollaboration. The book begins with Melinda Dooly & a chapter outlining the pedagogical and theoretical underpinnings of telecol- laboration (also known as Virtual Exchange), followed by eight chapters that Robert O’Dowd (eds) explain telecollaborative project design, materials and activities as well as frank discussions of obstacles met and resolved during the project imple- mentation. The projects described in the volume serve as excellent examples for any teacher or education stakeholder interested in setting up their own In This Together: telecollaborative exchange. -

Mary J. Schleppegrell

Mary J. Schleppegrell February, 2020 School of Education University of Michigan 610 E. University Ave. Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1259 734-647-2449 Education Ph.D., Linguistics, 1989 Georgetown University, Washington, DC M.A., Teaching English as a Foreign Language, 1982 American University in Cairo, Cairo, Egypt Multiple Subjects Teaching Credential, 1978 California State University, Sacramento, CA B.A., summa cum laude, German, 1972 University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN Experience • Professor of Education, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. 2005-present. • Chair, Educational Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. 2012-2015. • Professor of Linguistics, University of California, Davis, CA., 2004-2005. • Chair, Linguistics Graduate Group, University of California, Davis, CA. 2002-2005. • Member, Education Graduate Group, University of California, Davis, CA. 1997-2005. • Associate Professor of Linguistics, University of California, Davis, CA. 1998-2004. • Director of English as a Second Language, University of California, Davis, CA. 1992- 2003. • Assistant Professor of Linguistics, University of California, Davis, CA. 1992-1998. • Education Specialist, Peace Corps, Washington, DC, 1989-1992. • Language and Training Specialist, Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, DC, 1985-1989. • Consultant for Language Training Program Development, Cairo, Egypt and Washington, DC, 1981-85. • Instructor, Freshman Writing Program, American University in Cairo, Cairo, Egypt, 1980-82. • Master Teacher, California State University, Sacramento, teacher education program, 1979-80. • Teacher, Grades K-6, Elk Grove Independent School District, Elk Grove, CA, 1977-80. 1 Schleppegrell Publications Books, articles, and book chapters Krishnan, J., M. J. Schleppegrell, P. Collins, M. Warschauer. (Forthcoming May 2020) Supporting a language-focused approach to close reading in middle school English Language Arts. -

Virtual Exchange and Internationalising the Classroom

Virtual Exchange and internationalising the classroom Virtual Exchange and internationalising the classroom by Robert O’Dowd by Robert O’Dowd a long history in university language education ‘The first examples of online Robert O’Dowd University of León [email protected] (Warschauer, 1995) and, over the past two Published in Training, Language and Culture Vol 1 Issue 4 (2017) pp. 8-24 doi: 10.29366/2017tlc.1.4.1 collaborative projects between decades, approaches to Virtual Exchange have Recommended citation format: O’Dowd, R. (2017). Virtual Exchange and internationalising the classroom. classrooms around the globe evolved in different contexts and different areas of Training Language and Culture, 1(4), 8-24. doi: 10.29366/2017tlc.1.4.1 university education and these approaches have began to appear within a few Telecollaboration, or ‘Virtual Exchange’ refers to the application of online communication tools to bring together years of the emergence of the classes of learners in geographically distant locations with the aim of developing their foreign language skills, digital had, at times, very diverse pedagogical objectives. competence and intercultural competence through online collaborative tasks and project work. In recent years For example, approaches in foreign language Internet’ approaches to Virtual Exchange have evolved in different contexts and different areas of university education and these approaches have had, at times, very diverse organisational structures and pedagogical objectives. This article provides education have explored the development of an overview of the different models and approaches to Virtual Exchange which are currently being used in higher autonomy in language learners, foreign language appear within a few years of the emergence of the education contexts and outlines how the activity has contributed to internationalising university education to date.