Effects of Man on the Vegetation in the National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972.PDF

Version: 1.7.2015 South Australia National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 An Act to provide for the establishment and management of reserves for public benefit and enjoyment; to provide for the conservation of wildlife in a natural environment; and for other purposes. Contents Part 1—Preliminary 1 Short title 5 Interpretation Part 2—Administration Division 1—General administrative powers 6 Constitution of Minister as a corporation sole 9 Power of acquisition 10 Research and investigations 11 Wildlife Conservation Fund 12 Delegation 13 Information to be included in annual report 14 Minister not to administer this Act Division 2—The Parks and Wilderness Council 15 Establishment and membership of Council 16 Terms and conditions of membership 17 Remuneration 18 Vacancies or defects in appointment of members 19 Direction and control of Minister 19A Proceedings of Council 19B Conflict of interest under Public Sector (Honesty and Accountability) Act 19C Functions of Council 19D Annual report Division 3—Appointment and powers of wardens 20 Appointment of wardens 21 Assistance to warden 22 Powers of wardens 23 Forfeiture 24 Hindering of wardens etc 24A Offences by wardens etc 25 Power of arrest 26 False representation [3.7.2015] This version is not published under the Legislation Revision and Publication Act 2002 1 National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972—1.7.2015 Contents Part 3—Reserves and sanctuaries Division 1—National parks 27 Constitution of national parks by statute 28 Constitution of national parks by proclamation 28A Certain co-managed national -

Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project

Submission to Senate Inquiry: Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project: Potential Impacts on Matters of National Environmental Significance within Modelled Oil Spill Impact Areas (Summer and Winter 2A Model Scenarios) Prepared by Dr David Ellis (BSc Hons PhD; Ecologist, Environmental Consultant and Founder at Stepping Stones Ecological Services) March 27, 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 4 Summer Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................. 5 Winter Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................... 7 Threatened Species Conservation Status Summary ........................................... 8 International Migratory Bird Agreements ............................................................. 8 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11 Methods .................................................................................................................... 12 Protected Matters Search Tool Database Search and Criteria for Oil-Spill Model Selection ............................................................................................................. 12 Criteria for Inclusion/Exclusion of Threatened, Migratory and Marine -

Eyre Peninsula Groundwater Dependent Ecosystem Data Analysis: Wetland Condition Data for Lake Pillie and Sleaford Mere

Eyre Peninsula Groundwater Dependent Ecosystem Data Analysis: Wetland condition data for Lake Pillie and Sleaford Mere A report for Natural Resources Eyre Peninsula, Department of Environment and Water, Port Lincoln, South Australia. Prepared by: Kerri Muller NRM Pty. Ltd. Authors: Dr. Kerri Muller and Dr. Jason Nicol with Dr. Alison Charles from Water Technology Pty. Ltd. Date: 26 June 2020 Reference: 7219/CE394 Document Management Version Date Released Authors Released by Released to v0.1 5 June 2020 K.L. Muller & J. Nicol K.L. Muller A. Freeman Draft report for discussion Draft for comment 15 June 2020 K.L. Muller & J. Nicol K.L. Muller A. Freeman Final 26 June 2020 K.L. Muller & J. Nicol K.L. Muller A. Freeman Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank the staff of Natural Resources Eyre Peninsula, especially Andrew Freeman, Ben Smith, Greg Kerr and Michelle Clanahan, who developed the monitoring program, collected the field data, provided valuable insights, reviewed our initial data analysis and assisted with report finalisation. We would also like to thank Alison Charles from Water Technology Pty. Ltd., for preparing the groundwater and rainfall graphs. To contact the authors: Dr. Kerri Muller Kerri Muller NRM Pty. Ltd. PO Box 203 Victor Harbor SA 5211 E: [email protected] Disclaimer Kerri Muller NRM Pty. Ltd. (KMNRM) do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. KMNRM expressly disclaims all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. -

Southern Eyre Subregional Description

Southern Eyre Subregional Description Landscape Plan for Eyre Peninsula - Appendix C Southern Eyre comprises a land area of around 6,500 square kilometres, along with a large marine area. The southern boundary extends east from Spencer Gulf to the Southern Ocean, while the northern boundary extends along the agricultural plains north of Cummins. QUICK STATS Population: Approximately 23,500 Major towns (population): Port Lincoln (16,000), Tumby Bay (1,474), Cummins (719), Coffin Bay (615) Traditional Owners: Barngarla and Nauo nations Local Governments: Port Lincoln City Council, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula and District Council of Tumby Bay Land Area: Approximately 6,500 square kilometres Main land uses (% of land area): Cropping and grazing (63%), conservation (34%) Main industries: Fishing, aquaculture, agriculture, retail trade, health and community services, tourism, construction, mining Annual Rainfall: 340 – 560mm Highest elevation: Marble Range (436 metres AHD) Coastline length: 710 kilometres (excludes islands) Number of Islands: 113 2 Southern Eyre Subregional Description Southern Eyre What’s valued in Southern Eyre enjoy camping, 4WD adventures and walking. The pristine environment at Memory Cove and Coffin The Southern Eyre community is intrinsically linked Bay’s remoteness and wildness, provide a sense of to the natural environment with its identity ingrained adventure and place. in the “great outdoors”. Many people have their own favourite spot where they go to unwind and feel a Sir Joseph Banks Group are magic sense of place. For some it is their own patch, for parts of the world. They have an others it is a secluded beach or an adventure in the abundance of marine and birdlife bush. -

The Coastal Talitridae (Amphipoda: Talitroidea) of Southern and Western Australia, with Comments on Platorchestia Platensis (Krøyer, 1845)

© The Authors, 2008. Journal compilation © Australian Museum, Sydney, 2008 Records of the Australian Museum (2008) Vol. 60: 161–206. ISSN 0067-1975 doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.60.2008.1491 The Coastal Talitridae (Amphipoda: Talitroidea) of Southern and Western Australia, with Comments on Platorchestia platensis (Krøyer, 1845) C.S. SEREJO 1 AND J.K. LOWRY *2 1 Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Quinta da Boa Vista s/n, Rio de Janeiro, RJ 20940–040, Brazil [email protected] 2 Crustacea Section, Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia [email protected] AB S TRA C T . A total of eight coastal talitrid amphipods from Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia are documented. Three new genera (Australorchestia n.gen.; Bellorchestia n.gen. and Notorchestia n.gen.) and seven new species (Australorchestia occidentalis n.sp.; Bellorchestia richardsoni n.sp.; Notorchestia lobata n.sp.; N. naturaliste n.sp.; Platorchestia paraplatensis n.sp. Protorchestia ceduna n.sp. and Transorchestia marlo n.sp.) are described. Notorchestia australis (Fearn-Wannan, 1968) is reported from Twofold Bay, New South Wales, to the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. Seven Australian and New Zealand “Talorchestia” species are transferred to Bellorchestia: B. chathamensis (Hurley, 1956); B. kirki (Hurley, 1956); B. marmorata (Haswell, 1880); B. pravidactyla (Haswell, 1880); B. quoyana (Milne Edwards, 1840); B. spadix (Hurley, 1956) and B. tumida (Thomson, 1885). Two Australian “Talorchestia” species are transferred to Notorchestia: N. australis (Fearn-Wannan, 1968) and N. novaehollandiae (Stebbing, 1899). Type material of Platorchestia platensis and Protorchestia lakei were re-examined for comparison with Australian species herein described. -

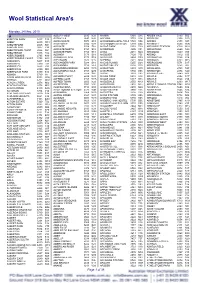

Wool Statistical Area's

Wool Statistical Area's Monday, 24 May, 2010 A ALBURY WEST 2640 N28 ANAMA 5464 S15 ARDEN VALE 5433 S05 ABBETON PARK 5417 S15 ALDAVILLA 2440 N42 ANCONA 3715 V14 ARDGLEN 2338 N20 ABBEY 6280 W18 ALDERSGATE 5070 S18 ANDAMOOKA OPALFIELDS5722 S04 ARDING 2358 N03 ABBOTSFORD 2046 N21 ALDERSYDE 6306 W11 ANDAMOOKA STATION 5720 S04 ARDINGLY 6630 W06 ABBOTSFORD 3067 V30 ALDGATE 5154 S18 ANDAS PARK 5353 S19 ARDJORIE STATION 6728 W01 ABBOTSFORD POINT 2046 N21 ALDGATE NORTH 5154 S18 ANDERSON 3995 V31 ARDLETHAN 2665 N29 ABBOTSHAM 7315 T02 ALDGATE PARK 5154 S18 ANDO 2631 N24 ARDMONA 3629 V09 ABERCROMBIE 2795 N19 ALDINGA 5173 S18 ANDOVER 7120 T05 ARDNO 3312 V20 ABERCROMBIE CAVES 2795 N19 ALDINGA BEACH 5173 S18 ANDREWS 5454 S09 ARDONACHIE 3286 V24 ABERDEEN 5417 S15 ALECTOWN 2870 N15 ANEMBO 2621 N24 ARDROSS 6153 W15 ABERDEEN 7310 T02 ALEXANDER PARK 5039 S18 ANGAS PLAINS 5255 S20 ARDROSSAN 5571 S17 ABERFELDY 3825 V33 ALEXANDRA 3714 V14 ANGAS VALLEY 5238 S25 AREEGRA 3480 V02 ABERFOYLE 2350 N03 ALEXANDRA BRIDGE 6288 W18 ANGASTON 5353 S19 ARGALONG 2720 N27 ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 S18 ALEXANDRA HILLS 4161 Q30 ANGEPENA 5732 S05 ARGENTON 2284 N20 ABINGA 5710 18 ALFORD 5554 S16 ANGIP 3393 V02 ARGENTS HILL 2449 N01 ABROLHOS ISLANDS 6532 W06 ALFORDS POINT 2234 N21 ANGLE PARK 5010 S18 ARGYLE 2852 N17 ABYDOS 6721 W02 ALFRED COVE 6154 W15 ANGLE VALE 5117 S18 ARGYLE 3523 V15 ACACIA CREEK 2476 N02 ALFRED TOWN 2650 N29 ANGLEDALE 2550 N43 ARGYLE 6239 W17 ACACIA PLATEAU 2476 N02 ALFREDTON 3350 V26 ANGLEDOOL 2832 N12 ARGYLE DOWNS STATION6743 W01 ACACIA RIDGE 4110 Q30 ALGEBUCKINA -

Conserving Marine Biodiversity in South Australia - Part 1 - Background, Status and Review of Approach to Marine Biodiversity Conservation in South Australia

Conserving Marine Biodiversity in South Australia - Part 1 - Background, Status and Review of Approach to Marine Biodiversity Conservation in South Australia K S Edyvane May 1999 ISBN 0 7308 5237 7 No 38 The recommendations given in this publication are based on the best available information at the time of writing. The South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI) makes no warranty of any kind expressed or implied concerning the use of technology mentioned in this publication. © SARDI. This work is copyright. Apart of any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the publisher. SARDI is a group of the Department of Primary Industries and Resources CONTENTS – PART ONE PAGE CONTENTS NUMBER INTRODUCTION 1. Introduction…………………………………..…………………………………………………………1 1.1 The ‘Unique South’ – Southern Australia’s Temperate Marine Biota…………………………….…….1 1.2 1.2 The Status of Marine Protected Areas in Southern Australia………………………………….4 2 South Australia’s Marine Ecosystems and Biodiversity……………………………………………..9 2.1 Oceans, Gulfs and Estuaries – South Australia’s Oceanographic Environments……………………….9 2.1.1 Productivity…………………………………………………………………………………….9 2.1.2 Estuaries………………………………………………………………………………………..9 2.2 Rocky Cliffs and Gulfs, to Mangrove Shores -South Australia’s Coastal Environments………………………………………………………………13 2.2.1 Offshore Islands………………………………………………………………………………14 2.2.2 Gulf Ecosystems………………………………………………………………………………14 2.2.3 Northern Spencer Gulf………………………………………………………………………...14 -

Environmental Water Requirements of Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems in the Musgrave and Southern Basins Prescribed Wells Areas on the Eyre Peninsula 2012/16

TECHNICAL REPORT ENVIRONMENTAL WATER REQUIREMENTS OF GROUNDWATER DEPENDENT ECOSYSTEMS IN THE MUSGRAVE AND SOUTHERN BASINS PRESCRIBED WELLS AREAS ON THE EYRE PENINSULA 2012/16 DISCLAIMER The Department for Water and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of use of the information contained herein as to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The Department for Water and its employees expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice ENVIRONMENTAL WATER REQUIREMENTS OF GROUNDWATER DEPENDENT ECOSYSTEMS IN THE MUSGRAVE AND SOUTHERN BASINS PRESCRIBED WELLS AREAS ON THE EYRE PENINSULA Tim Doeg, Kerri Muller, Jason Nicol and Jason VanLaarhoven Science, Monitoring and Information Division Department for Water June 2012 Technical Report DFW 2012/16 Science, Monitoring and Information Division Department for Water 25 Grenfell Street, Adelaide GPO Box 2834, Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone National (08) 8463 6946 International +61 8 8463 6946 Fax National (08) 8463 6999 International +61 8 8463 6999 Website www.waterforgood.sa.gov.au Disclaimer The Department for Water and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The Department for Water and its employees expressly disclaims all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. Information contained in this document is correct at the time of writing. © Government of South Australia, through the Department for Water 2012 This work is Copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cwlth), no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission obtained from the Department for Water. -

Coastal Landscapes of South Australia

Welcome to the electronic edition of Coastal Landscapes of South Australia. The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page. Click on this anytime to return to the contents. You can also add your own bookmarks. Each chapter heading in the contents table is clickable and will take you direct to the chapter. Return using the contents link in the bookmarks. The whole document is fully searchable. Enjoy. Coastal Landscapes of South Australia This book is available as a free fully-searchable ebook from www.adelaide.edu.au/press Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press Barr Smith Library, Level 3.5 The University of Adelaide South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The University of Adelaide Press publishes peer reviewed scholarly books. It aims to maximise access to the best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high quality printed volumes. © 2016 Robert P. Bourman, Colin V. Murray-Wallace and Nick Harvey This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for the copying, distribution, display and performance of this work for non-commercial purposes providing the work is clearly attributed to the copyright holders. Address all inquiries to the Director at the above address. -

Terrestrial and Marine Protected Areas in Australia

TERRESTRIAL AND MARINE PROTECTED AREAS IN AUSTRALIA 2002 SUMMARY STATISTICS FROM THE COLLABORATIVE AUSTRALIAN PROTECTED AREAS DATABASE (CAPAD) Department of the Environment and Heritage, 2003 Published by: Department of the Environment and Heritage, Canberra. Citation: Environment Australia, 2003. Terrestrial and Marine Protected Areas in Australia: 2002 Summary Statistics from the Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database (CAPAD), The Department of Environment and Heritage, Canberra. This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from Department of the Environment and Heritage. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Assistant Secretary Parks Australia South Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601. The views and opinions expressed in this document are not necessarily those of the Commonwealth of Australia, the Minister for Environment and Heritage, or the Director of National Parks. Copies of this publication are available from: National Reserve System National Reserve System Section Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 or online at http://www.deh.gov.au/parks/nrs/capad/index.html For further information: Phone: (02) 6274 1111 Acknowledgments: The editors would like to thank all those officers from State, Territory and Commonwealth agencies who assisted to help compile and action our requests for information and help. This assistance is highly appreciated and without it and the cooperation and help of policy, program and GIS staff from all agencies this publication would not have been possible. An additional huge thank you to Jason Passioura (ERIN, Department of the Environment and Heritage) for his assistance through the whole compilation process. -

Although They Are Most Widespread in the Vicinity of Robinson Lens and the Southern Basins PWA

Eyre Peninsula Groundwater Dependent Ecosystem Scoping Study 5.6. Extent of phreatophytes Phreatophytes occur within all three study areas (Figure 5.13, Figure 5.14 and Figure 5.15), although they are most widespread in the vicinity of Robinson lens and the Southern Basins PWA. In the Southern Basins area, mapped areas inferred to be obligate phreatophytes are present in small pockets in the north and east of the region, overlying the northern edges of Uley Wanilla and Uley East, surrounding Big Swamp, as well as to the east near Lincoln-D and Tulka lenses. These obligate phreatophytes mainly occur outside the study area, beyond the northern boundary of the PWA. Facultative phreatophytes over deep water tables are common in the Southern Basins, with several relatively large expanses of mapped vegetation across the area. A significant portion of the mapped potentially phreatophytic vegetation in the area lies above unknown water tables and hence could potentially be groundwater dependent. In the Musgrave area, obligate phreatophytes are the most common of those classified, mostly occurring as small pockets in the vicinity of Kappawanta and Sheringa lenses. Facultative phreatophytes are also present in this area; small pockets occurring over the shallow water tables that exist close to Polda, Bramfield and Talia lenses. A significant portion of the phreatophytes identified in the Musgrave area have insufficient data to make conclusions about their dependence on groundwater and hence are potentially groundwater dependent. In the vicinity of Robinson lens, facultative phreatophytes over shallow water tables are the most common, covering a significant portion of the lens itself. -

Lincoln National Park Management Plan

Department for Environment and Heritage Management Plan Lincoln National Park Incorporating Lincoln Conservation Reserve 2004 Our Parks, Our Heritage, Our Legacy Cultural richness and diversity are the hallmarks of a great society. It is these qualities that are basic to our humanity. They are the foundation of our value systems and drive our quest for purpose and contentment. Cultural richness embodies morality, spiritual well-being, the rule of law, reverence for life, human achievement, creativity and talent, options for choice, a sense of belonging, personal worth and an acceptance of responsibility for the future. Biological richness and diversity are, in turn, important to cultural richness and communities of people. When a community ceases to value and protect its natural landscapes, it erodes the richness and wholeness of its cultural foundation. In South Australia, we are privileged to have a network of parks, reserves and protected areas that continue to serve as benchmarks against which we can measure progress and change brought about by our society. They are storehouses of nature’s rich diversity, standing as precious biological and cultural treasures. It is important to realise that survival of species in ‘island’ reserves surrounded by agriculture or urban areas is uncertain, and that habitat links between reserves are essential for their long-term value as storehouses. As a result of more than a century of conserving nature and cultural items, we possess a “legacy” which is worth passing on to future generations. There are twelve essentials for the protection of our park environments: • Recognition that a primary purpose of our national parks system is to conserve the wide diversity of South Australia’s native plants and animals and to improve their chances of survival through active wildlife management.