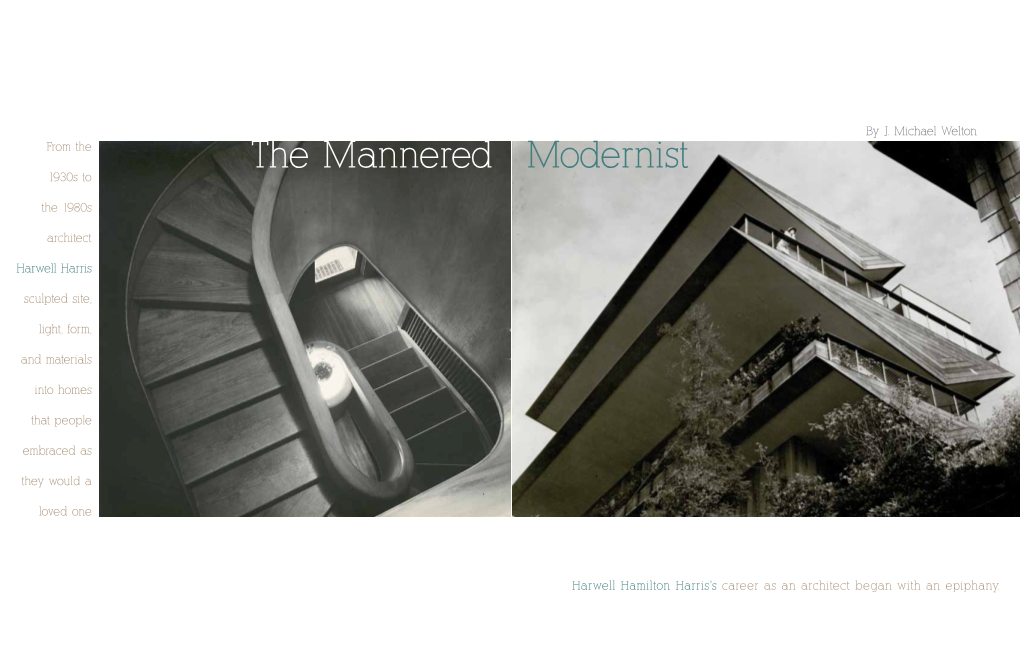

The Mannere Mo Ernist 1930S To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Challenges and Achievements

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture NISEI ARCHITECTS: CHALLENGES AND ACHIEVEMENTS A Thesis in Architecture by Katrin Freude © 2017 Katrin Freude Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Architecture May 2017 The Thesis of Katrin Freude was reviewed and approved* by the following: Alexandra Staub Associate Professor of Architecture Thesis Advisor Denise Costanzo Associate Professor of Architecture Thesis Co-Advisor Katsuhiko Muramoto Associate Professor of Architecture Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History Ute Poerschke Associate Professor of Architecture Director of Graduate Studies *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii Abstract Japanese-Americans and their culture have been perceived very ambivalently in the United States in the middle of the twentieth century; while they mostly faced discrimination for their ethnicity by the white majority in the United States, there has also been a consistent group of admirers of the Japanese art and architecture. Nisei (Japanese-Americans of the second generation) architects inherited the racial stigma of the Japanese minority but increasingly benefited from the new aesthetic light that was cast, in both pre- and post-war years, on Japanese art and architecture. This thesis aims to clarify how Nisei architects dealt with this ambivalence and how it was mirrored in their professional lives and their built designs. How did architects, operating in the United States, perceive Japanese architecture? How did these perceptions affect their designs? I aim to clarify these influences through case studies that will include such general issues as (1) Japanese-Americans’ general cultural evolution, (2) architects operating in the United States and their relation to Japanese architecture, and (3) biographies of three Nisei architects: George Nakashima, Minoru Yamasaki, and George Matsumoto. -

An Introduction to Architectural Theory Is the First Critical History of a Ma Architectural Thought Over the Last Forty Years

a ND M a LLGR G OOD An Introduction to Architectural Theory is the first critical history of a ma architectural thought over the last forty years. Beginning with the VE cataclysmic social and political events of 1968, the authors survey N the criticisms of high modernism and its abiding evolution, the AN INTRODUCT rise of postmodern and poststructural theory, traditionalism, New Urbanism, critical regionalism, deconstruction, parametric design, minimalism, phenomenology, sustainability, and the implications of AN INTRODUCTiON TO new technologies for design. With a sharp and lively text, Mallgrave and Goodman explore issues in depth but not to the extent that they become inaccessible to beginning students. ARCHITECTURaL THEORY i HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE is a professor of architecture at Illinois Institute of ON TO 1968 TO THE PRESENT Technology, and has enjoyed a distinguished career as an award-winning scholar, translator, and editor. His most recent publications include Modern Architectural HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE aND DaViD GOODmaN Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673–1968 (2005), the two volumes of Architectural ARCHITECTUR Theory: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 2005 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005–8, volume 2 with co-editor Christina Contandriopoulos), and The Architect’s Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). DaViD GOODmaN is Studio Associate Professor of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology and is co-principal of R+D Studio. He has also taught architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and at Boston Architectural College. His work has appeared in the journal Log, in the anthology Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives, and in the Northwestern University Press publication Walter Netsch: A Critical Appreciation and Sourcebook. -

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2019-4766-HCM ENV-2019-4767-CE HEARING DATE: September 5, 2019 Location: 2421-2425 North Silver Ridge Avenue TIME: 10:00 AM Council District: 13 – O’Farrell PLACE : City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: Silver Lake – Echo Park – 200 N. Spring Street Elysian Valley Los Angeles, CA 90012 Area Planning Commission: East Los Angeles Neighborhood Council: Silver Lake Legal Description: Tract 6599, Lots 15-16 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the HAWK HOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property an Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER/ Bryan Libit APPLICANT: 2421 Silver Ridge Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90039 PREPARER: Jenna Snow PO Box 5201 Sherman Oaks, CA 91413 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Take the property under consideration as an Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10 because the application and accompanying photo documentation suggest the submittal warrants further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. VINCENT P. BERTONI, AICP Director of PlanningN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Melissa Jones, City Planning Associate Office of Historic Resources Attachment: Historic-Cultural Monument Application CHC-2019-4766-HCM 2421-2425 Silver Ridge Avenue Page 2 of 3 SUMMARY The Hawk House is a two-story single-family residence and detached garage located on Silver Ridge Avenue in Silver Lake. Constructed in 1939, it was designed by architect Harwell Hamilton Harris (1903-1990) in the Early Modern architectural style for Edwin “Stan” Stanton and Ethyle Hawk. -

Los Angeles City Planning Department

RALPH JOHNSON HOUSE 10261 Chrysanthemum Lane CHC-2016-508-HCM ENV-2016-509-CE Agenda packet includes 1. Final Staff Recommendation Report 2. Categorical Exemption 3. Under Consideration Staff Recommendation Report 4. Nomination Please click on each document to be directly taken to the corresponding page of the PDF. Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2016-508-HCM ENV-2016-509-CE Location: 10261 Chrysanthemum Lane HEARING DATE: April 21, 2016 Council District: 5 TIME: 9:00 AM Community Plan Area: Bel-Air Beverly Crest PLACE : City Hall, Room 1010 Area Planning Commission: West 200 N. Spring Street Neighborhood Council: Bel-Air Beverly Crest Los Angeles, CA 90012 Legal Description: TR 1033, Block 31, Lot 15, 16, EXPIRATION DATE: May 17, 2016 53, 54, and 55 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the RALPH JOHNSON HOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER/ Viet-Nu Nguyen APPLICANT: 10261 Chrysanthemum Lane Los Angeles, CA 90077 PREPARER: Anna Marie Brooks 1109 4th Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90019 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Declare the subject property a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.7. 2. Adopt the staff report and findings. VINCENT P. BERTONI, AICP Director of PlanningN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Shannon Ryan, City Planning Associate Office of Historic Resources Attachments: Historic-Cultural Monument Application CHC-2016-508-HCM 10261 Chrysanthemum Lane Page 2 of 4 FINDINGS The Ralph Johnson House "embodies the distinguishing characteristics of an architectural-type specimen, inherently valuable for study of a period, style or method of construction” as an example of the Mid-Century Modern style with heavy Craftsman influences. -

EAMES HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 EAMES HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Eames House Other Name/Site Number: Case Study House #8 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 203 N Chautauqua Boulevard Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Pacific Palisades Vicinity: N/A State: California County: Los Angeles Code: 037 Zip Code: 90272 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: x Building(s): x Public-Local: _ District: Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing: Noncontributing: 2 buildings sites structures objects Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: None Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 EAMES HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

History.Pdf (1.893Mb)

©1996 Michael Vallen A view of Los Angeles from the Thesis site. “Oh, it will become bigger and bigger and extend itself north and south. And soon Los Angeles will begin in San Diego, swallow San Francisco and pave every acre of earth up to the Gold River. The only historic monuments spared will be the rest rooms in the gasoline stations.” Attributed to Frank Lloyd Wright, late 1950s 4 Los Angeles is a city apart, not only in derived from a popular Spanish novel of gold, and territorial conquest were the significant trade among the estimated 500 location, but in ideals and pursuits. This city, 1510, in which a terrestrial paradise is motivations of the Spanish. Instead the tribal groups of the region. They possessed little understood, has been, and is, the described... Spanish discovered the coast of California. a strictly organized religious system, a keen model from which we currently fabricate our “Know-ye that at the right hand of the It was Juan Cabrillo, who in late 1542, became knowledge of plant and animal material, metropolitan areas; an experiment in urban Indies there is an island called California, the first European to meet the native people and an intricate architectural language that and social planning unlike any previously very near the terrestrial Paradise...It is the of the Los Angeles Basin, the Gabrielino linked all parts of their structures to their known to humanity. To some these grand spiritual beliefs. experiments have failed, miserably; to others, not only have these experiments The Spanish were not interested in con- been a success, but they have also forged the quering the Gabrielinos. -

Art Ltd | West Coast Art+Design

ART LTD | WEST COAST ART+DESIGN http://www.artltdmag.com/article.php?misc=search&subaction=showfull&id=11... ART on the edge Architecture tours were invented for people like me – the voyeurs who spend too DESIGN much time crowding the bougainvillea looking for a glimpse of the staircase or Interior roofline of a well-hidden gem. No matter how dog-eared your guidebook, or Exterior how familiar you are with the recent restorations of mid-century relics or the Architecture cutting edge buildings by local architects, too much of the city’s great architecture Profiles hides behind fences and walls or is tucked along hillsides, invisible to even the CALENDAR intrepid observer. Tours give us the opportunity to legitimately walk through the front door of a Lautner house, an original case study design, or a cluster of ADVERTISING Neutra houses – with no guilt – and soak up the expanses of glass, steel case SUBSCRIBE frames and original wood details. These days, architecture tours in and around Los Angeles have become their own version of a hot little art show with many tours highlighting the homes the way museum exhibits showcase premiere paintings. After all, Los Angeles is search considered the jewel box of mid-century modernism, with premiere examples throughout. And these days that architecture is being collected, restored, and sold like art, piquing the interest in these homes that are often hidden in the hillsides. ABOUT US From the Valley to Palm Springs, from Silverlake to the Westside, fabulous houses are being showcased on tours by well-established organizations like The CONTACT US MAK Center and The Los Angeles Conservancy, new groups like CA Boom Design Shows, and small neighborhood groups like the Committee to Save SUBMIT Silverlake’s Reservoirs. -

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2015-2719-HCM ENV-2015-2720-CE HEARING DATE: August 6, 2015 Location: 1650 N. Queens Road TIME: 9:00 AM Council District: 4 PLACE: City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: Hollywood 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: Central Los Angeles, CA Neighborhood Council: Bel Air – Beverly Crest 90012 Legal Description: Tract TR 8500, Block None, Lot 135 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the POLITO HOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER/ Jared Stein APPLICANT: 1650 N. Queens Road Los Angeles, CA 90019 APPLICANT’S Charles J. Fisher REPRESENTATIVE: 140 S. Avenue 57 Highland Park, CA 90042 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Take the property under consideration as a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10 because the application and accompanying photo documentation suggest the submittal warrants further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. MICHAEL J. LOGRANDE Director of Planning [SIGN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE]ED ORIGINAL [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE]IN F [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Shannon Ryan, City Planning Associate Office of Historic Resources Attachments: Historic-Cultural Monument Application CHC-2015-2719-HCM 1650 N. Queens Road Page 2 of 2 SUMMARY Built in 1940, the Polito House is a Bauhaus-influenced, single family residence of the International Style. The house is set into the Hollywood hillside, with a three-story elevation built to the lot line facing Queens Road. -

Historic Landmark Report

7/09 Raleigh Department of City Planning Fee ___________________________ One Exchange Plaza Amt Paid ___________________________ 3rd floor Check # ___________________________ Raleigh, NC 27602 Rec’d Date: ___________________________ 919‐516‐2626 Rec’d By: ___________________________ Completion Date:________________________ www.raleighnc.gov/planning (Processing Fee: $257.00 - valid until June 30, 2010 - Checks payable to the City of Raleigh.) RALEIGH HISTORIC LANDMARK DESIGNATION APPLICATION This application initiates consideration of a property for designation as a Raleigh Historic Landmark by the Raleigh Historic Districts Commission (RHDC) and the Raleigh City Council. It enables evaluation of the resource to determine if it qualifies for designation. The evaluation is made by the Research Committee of the RHDC, which makes its recommendation to the full commission. The historic landmark program was previously administered by the Wake County Historic Preservation Commission but has been transferred back to the city; procedures for administration by the RHDC are outlined in the Raleigh City Code, Section 10-1053. Please type if possible. Use 8-1/2” x 11” paper for supporting documentation and if additional space is needed. All materials submitted become the property of the RHDC and cannot be returned. Return completed application to the RHDC office at One Exchange Plaza, Suite 300, Raleigh or mail to: Raleigh Historic Districts Commission PO Box 829 Century Station Raleigh, NC 27602 1. Name of Property (if historic name is unknown, give current name or street address): Historic Name: Harwell Hamilton & Jean Bangs Harris House and Studio Current Name: 2. Location: Street 122 Cox Avenue, Raleigh, NC 27605 Address: NC PIN No.: 1704005348 (Can be obtained from http://imaps.co.wake.nc.us/imaps/) 3. -

Recent Past Historic Context Report

Cultural Resources of the Recent Past Historic Context Report City of Pasadena Prepared by Historic Resources Group & Pasadena Heritage October 2007 Cultural Resources of the Recent Past Historic Context Report City of Pasadena Prepared for City of Pasadena 117 East Colorado Boulevard Pasadena, California 91105 Prepared by Historic Resources Group 1728 Whitley Avenue Hollywood, California 90028 & Pasadena Heritage 651 South Saint John Avenue Pasadena, California 91105 October 2007 Table of Contents I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ......................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 1 OBJECTIVES & SCOPE................................................................................ 2 METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................... 3 II. CRITERIA FOR EVALUATION................................................................... 6 NATIONAL REGISTER................................................................................. 6 CALIFORNIA REGISTER ............................................................................... 6 CITY OF PASADENA .................................................................................. 7 ASPECTS OF INTEGRITY .............................................................................. 8 III. HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT ...........................................................10 INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................10 -

Surveyla Survey Report Template

Historic Resources Survey Report Bel Air – Beverly Crest Community Plan Area Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources Prepared by: GPA Consulting, Inc. El Segundo, CA November 2013 Table of Contents Project Overview 1 SurveyLA Methodology Summary 1 Project Team 3 Survey Area 3 Designated Resources 11 Community Plan Area Survey Methodology 13 Summary of Findings 15 Summary of Property Types 15 Summary of Contexts and Themes 16 For Further Reading 42 Appendices Appendix A: Individual Resources Appendix B: Non-Parcel Resources Appendix C: Historic Districts & Planning Districts SurveyLA Bel Air–Beverly Crest Community Plan Area Project Overview This historic resources survey report (“Survey Report”) has been completed on behalf of the City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning’s Office of Historic Resources (OHR) for the SurveyLA historic resources survey of the Bel Air–Beverly Crest Community Plan Area (CPA). This project was undertaken from October 2012 to September 2013 by GPA Consulting, Inc. (GPA). This Survey Report provides a summary of the work completed, including a description of the Survey Area; an overview of the field methodology; a summary of relevant contexts, themes and property types; and complete lists of all recorded resources. This Survey Report is intended to be used in conjunction with the SurveyLA Field Results Master Report (“Master Report”) which provides a detailed discussion of SurveyLA methodology and explains the terms used in this report and associated appendices. The Master Report, Survey Report, and Appendices are available at www.surveyla.org SurveyLA Methodology Summary Below is a brief summary of SurveyLA methodology. -

City of Rancho Palos Verdes Class 2 Categorical

CITY OF RANCHO PALOS VERDES CLASS 2 CATEGORICAL EXEMPTION EVALUATION REPORT Ladera Linda Park and Community Center Project 32201 Forrestal Drive, Rancho Palos Verdes, CA 90275 This Exemption Evaluation Report documents the eligibility of the City of Rancho Palos Verdes’ Ladera Linda Park and Community Center Project for a Categorical Exemption from the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Project Description and Location Ladera Linda Park (Park) is a former elementary school site located at 32201 Forrestal Drive (Project Site) near the intersection with Pirate Drive in the southern portion of the City of Rancho Palos Verdes (see Figures 1 and 2). Amenities at the Park include paddle tennis courts, tot lot, playground, two basketball courts, restrooms, walking paths, and parking lots. The Park is also the home of the Discovery Room, which features static exhibits of local flora, fauna, and geologic information. Staff and volunteers (Los Serenos Docents) provide educational programs on-site for a large variety of school, youth, and other groups, as well as conduct docent-led hikes in the adjacent Forrestal Nature Reserve. The Park also has a multi-purpose room and classroom available for rental for meetings and private parties. The Park is located in the City-designated Institutional (I) zoning district. According to Section 17.26.050 of the Rancho Palos Verdes Municipal Code, any expansion of an existing development in the Institutional zoning district that involves either a new structure or an addition to an existing structure, which creates at least 500 square feet of additional floor area, shall require the approval of a conditional use permit (CUP).