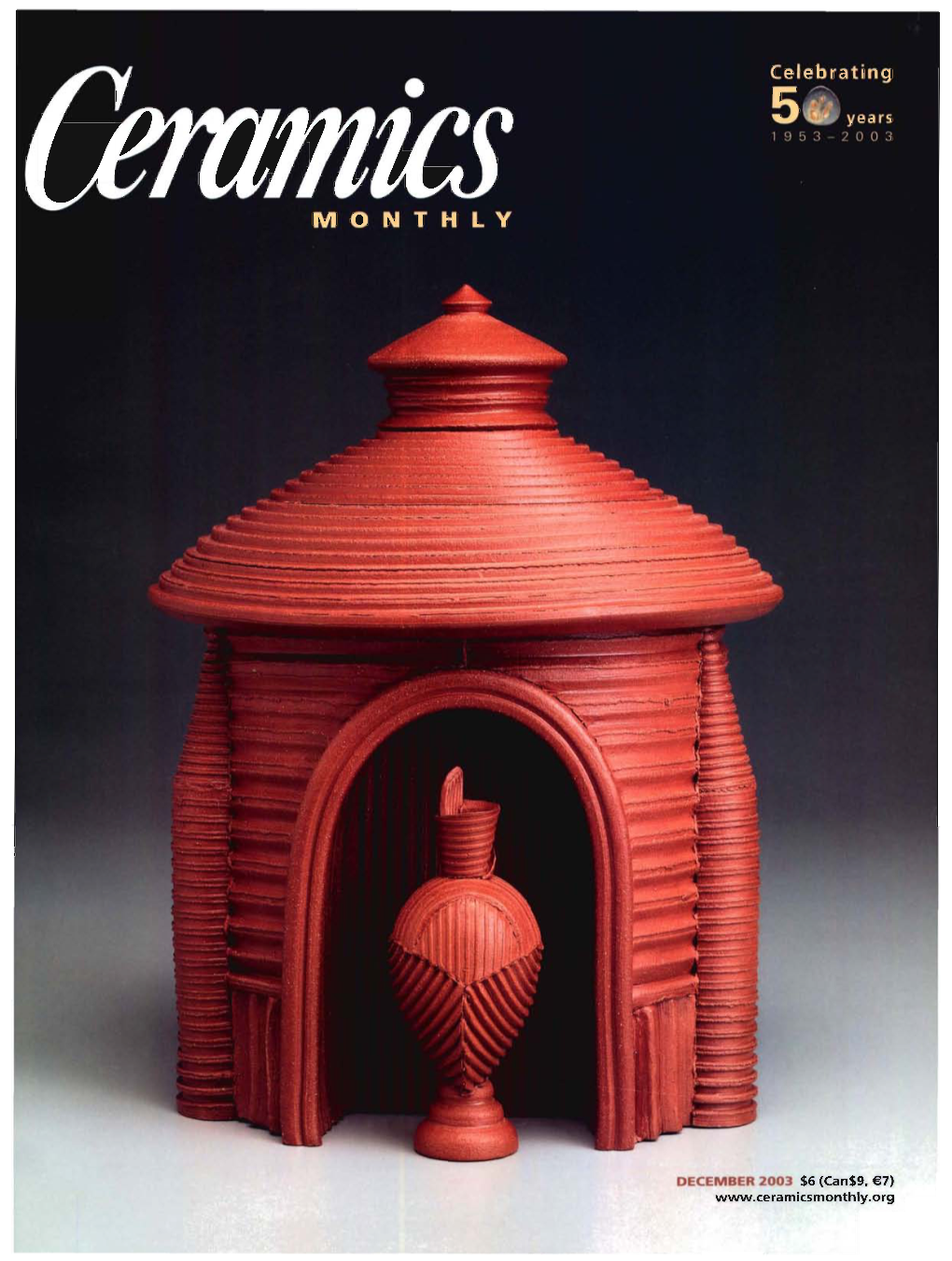

Ceramics Monthly Annual Index 112 Comment: Getting a Handle on Itby Tony Clennell 112 Index to Advertisers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESS RELEASE New Lease of Life for Burslem School Of

PRESS RELEASE New lease of life for Burslem School of Art Burslem School of Art, in the heart of the Mothertown, will soon be embarking on a new chapter in its illustrious history. From September 2016, 200 students from Haywood Sixth Form Academy will move into the newly refurbished grade II listed building to enjoy purpose-built facilities. A state-of-the-art design enterprise suite will be used for engineering product design and textiles. A specialist photography suite will house its own dark room and Apple Macs to enable students to learn digital photography skills. An ICT ‘window on the world’ room and specialist computing laboratory will provide students with leading-edge computer equipment and there will also be a specialist science lab and language lab. Students will develop their artistic talents in the magnificent art room, with its huge windows and perfect lighting for artwork, following in the footsteps of the Burslem School of Art’s prestigious alumni, including Clarice Cliff, Susie Cooper and William Moorcroft. The Burslem School of Art Trust carried out a refurbishment of the building in 2000 and has developed and delivered many arts events, projects and activities over the past fifteen years, working with diverse communities and artists. Now, Haywood Sixth Form Academy is working closely with the Trust to form a partnership that will build on its fantastic work and secure the future of this beautiful building. Carl Ward, Executive Headteacher, said: “Haywood Sixth Form Academy is becoming as popular as I had hoped when many parents and students asked if we would consider opening, just a few years ago. -

Susie Cooper

Ceramics Susie Cooper RDI - An Undervalued Legacy? by Roland Head ore than 100 years after her birth, Susie Cooper remains the only Mwoman potter to be awarded the prestigious RSA Royal Designer for Industry (RDI) award. Her career was longer than both the other two notable women, Clarice Cliff and Charlotte Rhead. Unlike them, she not only designed but founded and ran a successful pottery business on an industrial scale for many decades. Susie Cooper was one of the most important ceramic designers of the twentieth century, yet her work has less financial value and collectable A small plate in the Cubist pattern, dating from appeal than that of her contemporary, Clarice Cliff. Here I’ll explore her career Susie Cooper’s time at Gray’s. and work. I’ll also examine current prices and suggest how collectors should Image courtesy of www.decodance.com approach the market. Susie Cooper - The Art Deco Years used: she was not able to design her own shapes and simply Born in 1902, Susie Cooper was the youngest of seven decorated what she was given. Driven by a desire for greater children in a prosperous middle-class family. Her parents creative freedom and the belief she could do better herself, in owned several local businesses and her early experience of 1929 she resigned and founded the Susie Cooper Pottery. This work was gained in these establishments. Despite this, she was was to mark the beginning of a long and successful journey never tempted to make a career in the family businesses, and that would survive the depression of the 1930s, the Second by the age of sixteen had gained admission to the Burslem World War, two factory fires and multiple other setbacks. -

Momowo · 100 Works in 100 Years: European Women in Architecture

MoMoWo · 100 WORKS IN 100 YEARS 100 WORKS IN YEARS EUROPEAN WOMEN IN ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN · 1918-2018 · MoMoWo ISBN 978-961-254-922-0 9 789612 549220 not for sale 1918-2018 · DESIGN AND ARCHITECTURE IN WOMEN EUROPEAN Ljubljana - Torino MoMoWo . 100 Works in 100 Years European Women in Architecture and Design . 1918-2018 Edited by Ana María FERNÁNDEZ GARCÍA, Caterina FRANCHINI, Emilia GARDA, Helena SERAŽIN MoMoWo Scientific Committee: POLITO (Turin | Italy) Emilia GARDA, Caterina FRANCHINI IADE-U (Lisbon | Portugal) Maria Helena SOUTO UNIOVI (Oviedo | Spain) Ana Mária FERNÁNDEZ GARCÍA LU (Leiden | The Netherlands) Marjan GROOT ZRC SAZU (Ljubljana | Slovenia) Helena SERAŽIN UGA (Grenoble | France) Alain BONNET SiTI (Turin | Italy) Sara LEVI SACERDOTTI English language editing by Marta Correas Celorio, Alberto Fernández Costales, Elizabeth Smith Grimes Design and layout by Andrea Furlan ZRC SAZU, Žiga Okorn Published by France Stele Institute of Art History ZRC SAZU, represented by Barbara Murovec Issued by Založba ZRC, represented by Oto Luthar Printed by Agit Mariogros, Beinasco (TO) First edition / first print run: 3000 Ljubljana and Turin 2016 © 2016, MoMoWo © 2016, Založba ZRC, ZRC SAZU, Ljubljana http://www.momowo.eu Publication of the project MoMoWo - Women’s Creativity since the Modern Movement This project has been co-funded 50% by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Commission This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. This book was published on the occasion of the MoMoWo traveling exhibition MoMoWo · 100 Works in 100 Years · European Women in Architecture and Design · 1918-2018, which was first presented at the University of Oviedo Historical Building, Spain, from 1 July until 31 July 2016. -

Burslem Building Improvement Scheme (THI 3) Progress of Works

Burslem Building Improvement Scheme (THI 3) Progress of works Wedgwood Institute, Queen Street, Burslem Art school and library originally completed in 1863 with additions in 1869 and 1880 - this Grade II* listed brick and terracotta building has a richly ornamented façade and is arguably the most impressive looking building in the city. It is currently closed and some emergency repairs have been carried out. Proposals for the future use of the building are being discussed. Built in stages from 1859, by public subscription, and at an estimated cost of around £4,000, this remarkable building is named after Burslem’s iconic pottery-maker Josiah Wedgwood. The building stands on the site of the Brick House Works, which were rented by Wedgwood from 1762 to 1770. Original plans for the institute were created by G.B Nichols. The foundation stone was laid on 26th October 1863 by future Prime Minister William Gladstone. The amazing façade features designs by Robert Edgar and John Lockwood Kipling (father of novelist, Rudyard Kipling). It memorialises Wedgwood and celebrates the achievements of the enlightenment movement. It includes inlaid sculptures of pottery workers and processes, zodiac-sign mosiacs, terracotta panels that illustrate each month of the year, and a statue of Wedgwood himself. It also features portraits of Wedgwood’s fellow ‘principal’ Lunar Society colleagues - sculptor John Flaxman, scientist Joseph Priestly, business partner and industrialist Thomas Bentley. The Wedgwood Institute became a centre of excellence for the arts, sciences and business. It provided classes for the working men of the community. Notable students included novelist Arnold Bennett, ceramicist Graham Moorcroft, and physicist/ inventor Oliver Lodge. -

U.K. Pottery: by Company • U.K. Staffordshire Pottery

U.K. POTT ERY: BY COMPANY • U.K. STAFFORDSHIRE POTT ERY 139 Fireworks: New England Art Pottery of Royal Doulton: A Legacy of Excellence. The World of Wade: Figurines & Miniatures the Arts and Crafts Movement. Paul A. Gregg Whittecar and Arron Rimpley. The fi nest II. Ian Warner and Mike Posgay. Building on Royka. Arts and Crafts style New England art ceramic art wares produced by Royal Doulton the success and scope of The World of Wade pottery made from 1872 to 1928 displayed in at their Lambeth and Burslem Studios, dating Figurines and Miniatures, this revised and ex- over 400 color photos. Text examines the origins from the 1870s to 1945. Over 600 photos bring panded collector’s guide features hundreds of of the Arts and Crafts Movement and infl uences these treasures directly to life. The book features new and old fi gurines. New chapters include C&S manufacturing companies had on it. many of Doulton’s premier artists and their Collectables, Wade Fair special issues, and the Size: 8 1/2" x 11" • 450 color photos hand painted vases, vellum fi gures, and fl ambé, Goodie Box fi gurines and Christmas fi gurines. Price Guide • 192 pp. titanium, and experimental glazes. Size: 8 1/2" x 11" • 1867 color photos • Price ISBN: 0-88740-988-1 • hard cover • $69.95 Size: 9" x 12" • 600+ color photos guide • 392 pp. Value Reference • 288 pp. ISBN: 978-0-7643-3628-7 • hard cover • $49.99 ISBN: 0-7643-1797-0 • hard cover • $95.00 Schiffer LTD ANTIQUE U.K. -

Women Ceramic Designers of the Twentieth Century

Ceramics Coffee service by Lucie Rie from c1960 with manganese Susie Cooper tureen pattern 2222, showing how the lid could become and white glazes. a serving dish when turned upside down. Women ceramic designers of the twentieth century Clarice Cliff, Susie Cooper, Daisy Makeig-Jones & Dame Lucie Rie With four extra pages of Price Guides by Zita Thornton Traditionally women have always had a role in the SUSIE COOPER potteries as painters but some women went on to Susie Cooper was a contemporary of Clarice Cliff but her designs were very different. Apart from a brief period when her work become designers in their own right. I have embraced bright, abstract cubist patterns, her designs displayed chosen just four women designers who brought elegant, pastel patterns, many of them floral, on traditional shapes. innovation to twentieth century ceramic design. They appealed to customers of John Lewis for whom she produced an exclusive line featuring banded patterns and polka dots. They also appealed to Edward VIII and Mrs Simpson who ordered CLARICE CLIFF tableware in the delicate floral ‘Dresden Spray’ pattern, a design There can be few who have not heard of Clarice Cliff and most can which was popular for 25 years. identify the dazzling, bold style of her ‘Bizarre’ ware. However, Susie Cooper had a long career from 1922 until 1980. At an age prices for these pieces have escalated beyond the purses of most of when most people have been retired for several years, she was still us, but examples from the late 1930s, after the end of ‘Bizarre’ era, working and was awarded the Order of The British Empire in recog- still display her talent for innovation and remain more affordable. -

Two Day Sale of Antiques & Fine Art with Classic Cars & Automobilia

Two Day Sale of Antiques & Fine Art with Classic Cars & Automobilia, Northern & Contemporary Art, Medals & Militaria - Day One Thursday 10 April 2014 10:00 Adam Partridge Auctioneers & Valuers The Cheshire Saleroom Withyfold Drive Macclesfield SK10 2BD Adam Partridge Auctioneers & Valuers (Two Day Sale of Antiques & Fine Art with Classic Cars & Automobilia, Northern & Contemporary Art, Medals & Militaria - Day One ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Lot: 7 A 19th century walnut cased A 19th century walnut writing travelling decanter set, the slope, the hinged lid set with domed hinged lid enclosing six circular brass cartouche initialled clear glass gilt decorated ''GH'' enclosing leather lined decanters and with two later writing slope and pair of clear liqueur glasses to the lid, width of inkwells flanking a pen tray, width case 27cm, height of bottles 40cm. 18cm. Estimate: £60.00 - £100.00 Estimate: £200.00 - £400.00 Lot: 8 Lot: 2 An Edwardian oak single door An Edwardian oak decanter smoker's cabinet, 30 x 23cm. set/smoker's cabinet, the hinged Estimate: £20.00 - £40.00 lid above pair of doors enclosing three hobnail cut decanters, six glasses, tobacco jar and four various drawers, height 38cm, width 41cm. Estimate: £150.00 - £250.00 Lot: 9 Lot: 3 A chrome smoker's stand and a A miniature mahogany chest of Swedish Rorstrand lighter (2). three long drawers, height Estimate: £20.00 - £40.00 24.5cm. Estimate: £30.00 - £50.00 Lot: 10 Lot: 4 An Edwardian oak table top A Victorian rosewood writing smoker's cabinet with hinged lid slope (restored) and five small and two doors enclosing two pipe modern trinket boxes (6). -

Antique and Collectors Sale - Day Two Friday 25 October 2013 10:00

Antique and Collectors Sale - Day Two Friday 25 October 2013 10:00 Hansons Auctioneers & Valuers Heage Lane Etwall Derbyshire DE65 6LS Hansons Auctioneers & Valuers (Antique and Collectors Sale - Day Two) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 760 Lot: 763 Four Royal Doulton character Six pieces of Royal Crown Derby, jugs 'Nelson' 'Apothecary' Derby Posies pattern China, to 'Captain Ahab' and 'Neptune' (4) include H.M Queen 90th Birthday Estimate: £40.00 - £60.00 pin dish, small jug, tazza, etc (6) Estimate: £30.00 - £50.00 Lot: 760A Lot: 764 An Interesting Collection of Three Goebel, West German Clarice Cliff Items, by Ethel ceramic figures of children (3) Barrow, comprising a conical Estimate: £40.00 - £60.00 sugar castor, decorated with the crocus pattern, painted by Ethel Barrow (the crocus lady) signed EB, the inscription to base possibly later, together with five framed and double mounted watercolours, depicting various design patterns and a further framed set of six miniature Lot: 765 A Chinese blanc de chine watercolours, all double porcelain seated immortal, in mounted, all watercolours signed Kang xi style (1662 - 1722) 20 by Ethel Barrow, a small card cms h approx and another similar with a painted oval panel of figures (2) flowering foliage, painted by the Estimate: £30.00 - £40.00 artist aged 90. The collection comes with signatures on photocopied sheets depicting photographs of the illustrated people and a book entitled 'Taking Tea with Clarice Cliff', by Lot: 766 Leonard Griffin, 1996, the inside An Derby Falstaff Figure, finely cover bearing signatures of hand painted wearing a blue various painters who worked for overcoat with gilt decoration and Clarice Cliff, (9). -

New Zealand Potter Volume 37 Number 3 December 1995

IN THIS ISSUE THROUGH THE FILTER PRESS Howard Williams, Editorial 2 OBITUARY Susie Cooper, English Ceramic Designer 4 NEW ZEALAND POTTER VOLUME 37: NUMBER 3:1995 MOTOR CYCLISTS GO POTTY Waikato Museum '3 Exhibition of Motor Cycles and Pots 5 Editor: Howard S Williams RACHEL FULLER P.O. Box147, Albany, NZ. New sculptural work in clay 8 Phone 09 415 9817 THE PIONEERS Advertising: John Parker profiles Olive Jones 10 Cecilia Parkinson Phonel Fax 09 415 9373 GAS CENTRE CERAMICS AWARDS Mobile 025 820 034 Photos by Stephanie Leeves from the Waikato Exhibition 13 PO. Box 881 , Auckland. Zealand BLOOMSBURY Subscriptions: Gloria Young describes her Wellington co-operative studio and shop 14 Publisher and Distributor: NZ Potter Publications Ltd LUCIE RIE REMEMBERED PO Box 881, Auckland, NZ. John Parker's eulogy for this special lady Fax 09 309 3247 16 THE CLAY - ARCHITECTURE SHOW Managing Director: Sue Curnow reviews 3 Fisher Gallery Exhibition Cecilia Parkinson CANTA CLAY '96 Design and Layout: BB The NZSP Convention is introduced by Joan Moon Cecilia Parkinson, John Parker, Howard Williams THE POTTERS' CAMP GLAZES Di/ys Gill shares her recipe book collection from UK '3 Printed By: Imedia Corporation Ltd JOSIAH WEDGWOOD 71 Upper Queen Street Sally Vinson writes on the 200th Anniversary of the "Father of English Potters" Auckland, NZ SUVA IHC " Further information see Copy Deadlines: A visit to a disused Fijian pottery workshop, by Pattie Lloyd I enclosed entry form 1st day of February, June, September Issued: Apri|,August, December BUT WHAT IS IT? or write to: Price: $12 per copy incl GST Brian Gartside continues his computer experiments Annual Subscription: NZSP Inc $36 incl GST WORKS IN PROGRESS /0 Cecilia Parkinson OverseasSubscriptions by surface mail: A collaboration at Compendium Gallery, by John Parker and Terry Stringer NZ$48. -

Clarice and Her Contemporaries

Clarice and Her Contemporaries INTRODUCTION 1999 was the centenary of Clarice Cliff probably the best known woman pottery designer of the 20th century. She was a designer and pottery owner from the 1920s to the 1960s, but she is most famous for her hand painted designs of the 1920s and 30s. Few designers had their name included in the pottery backstamp but the influence of women on the development of Staffordshire ceramics in this period has become more widely recognised in recent years. CLARICE CLIFF Clarice Cliff was born on 20th January 1898 in Tunstall, Stoke-on-Trent. At fourteen she started work as a paintress for a local pottery. In 1916 she joined the firm of A.J.Wilkinson where she stayed for the rest of her working life. Clarice’s artistic talents were soon noticed. She started to work with the company’s designers and attended classes at Burslem School of Art. She was given her own studio at the factory and in 1927 her range of hand-painted Bizarre Ware was launched. Bizarre Ware was an immediate success. The designs were in the popular Art Deco style and were inexpensive. Clarice added hundreds of patterns to the original range, including the Fantasque and Inspirations series. She also designed the shapes of her pottery, often using geometric forms. In 1931 she became the company’s art director. During the war decorated pottery was made for export only. Clarice adapted her style to what would sell overseas, designing many printed patterns based on Victorian originals. Clarice married the owner of Wilkinson’s Pottery, Colley Shorter. -

The Subject Index

DAS Index – Subjects AA Journal 20.64 Aalto, Alvar 10.34–6, 19.48, 56, 27.16, 31.75 Abadie, Paul 14.6 Abbey, Edwin Austin 21.60, 24.50, 28.197 Abbey Theatre (Dublin) 9.29 Abbot Hall Museum (Kendal) 31.42 Abdulla Cigarettes 23.62–3 Abels, Gustaf 5.6 Abercrombie, Patrick 26.121, 127 Aberdeen 21.35–44 Argyll Place and Crescent 21.37, 39 Art Gallery 35.125 Ecclesiological Society (later Scottish Ecclesiological Society) 21.35, 41–2, 44 Episcopal Church 21.42 Hamilton Place 21.35, 37, 39 Philosophical Society 21.35 Queens Cross Church 21.37 St Machar’s Cathedral 23.40 Seaton Cottage 23.34 Society of Architects 21.35 Victoria Park fountain 21.35 West Kirk 23.42–3 Aberdeen Directory 21.35 Aberdeen, Ishbel-Maria, Lady 18.63 Abney Hall, Cheshire 25.54–5 Abspoel, Willem F. 7.34 Abu Dhabi 32.145 The Academy 23.93, 98 Academy of Fine Arts (Valenciennes) 21.119 Acatos (Peter) (pottery) 15.25 Accles and Pollock (furniture) 8.54 Ackroyd, Peter 35.77, 79 Acton Burnett Hall (Shrewsbury) 24.13 Acton, Sir Harold 35, 8.31–2, 35.136 Acton, William 8.32 Adam & Small 23.48 Adam, Robert 8.7, 33.62, 67 Adam, Stephen 23.33, 35, 48 Adam style 8.7, 9.45, 46 Adams, John 30.117 Adams, Katharine 28.193 Adams, Maurice B 26.61, 28.116 Adams, Percy 21.122 Adburgham, Alison 33.82, 34.38 Addams, Jane 28.67, 75 Addison, David 24.54 Addison, Ruth 33.14–15 Adelphi (London) 21.127–8 Adeney, Bernard 17.34 Adie Bros 17.61, 62 Adjani, Isabelle 22.87 Adler, Rose 1.38 Adlington, William Sampson 21.95 Admiralty Harbour (Dover) 21.109 Adnet, Jacques 27.18 Adnet, J.J. -

Other Antique U.S. Pottery • Antique U.K. Pottery by Company

52 OTHER ANTIQUE U.S. POttERY • ANTIQUE U.K. POttERY BY COMPANY Alternative American Ceramics, 1870- George Jones Ceramics 1861-1951. Robert Spode and Copeland: Over Two Hundred 1955: The Other American Art Pottery. Ken E. Cluett. Popular majolica wares and “Abbey” Years of Fine China and Porcelain. Steven Forster. This is the first-ever study of American blue and white transfer printed ceramics pro- Smith. Over 440 images display the ceramics art/studio pottery, dinnerware, and other func- duced by George Jones. Over 700 color photos made by Spode. From blue and white transfer tional wares, as well as china painting and other display table, tea, toilet, and ornamental wares. printed wares of the early 1800s to dinnerware ceramic decoration and design produced without A detailed history, pattern registration dates, patterns of the 1900s, they include sprig wares, a primary profit-making motivation. Details shapes, & manufacturer’s marks are provided. bone china table and tea sets, figurines, and works from the Saturday Evening Girls, the Geoffrey Godden has called this “...the ultimate stoneware candlesticks and loving cups. Works Progress Administration, and many others. work on this Stoke firm.” Size: 8 1/2" x 11" • 442 color photos Size: 8 1/2" x 11" • 306 color & b/w photos • 320 pp. Size: 8 1/2" x 11" • 790 photos & illus. Price Guide/Index • 192 pp. ISBN: 978-0-7643-3610-2 • hard cover • $59.99 Price Guide/Index • 288 pp. ISBN: 0-7643-2173-0 • hard cover • $39.95 Schiffer LTD ISBN: 0-7643-0470-4 • hard cover • $49.95 Biographies in American Ceramic Art: Mason’s Vista Ironstone.