2016 Front Cover 1994 Front Cover 1986 Front Cover 1980 Front Cover

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On-Trent City Council Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report 2016

Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Stoke- on-Trent City Council Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report 2016 Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report For further information on this document or to obtain it in other formats, please contact one of the Councils at: Stoke-on-Trent City Council Planning and Transportation Policy Civic Centre Glebe Street Stoke-on-Trent ST4 1HH Email: [email protected] Telephone: 01782 236339 Website: www.stoke.gov.uk/planningpolicy Or: Planning Policy Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Civic Offices Merrial Street Newcastle-under-Lyme Staffordshire ST5 2AG Email: [email protected] Telephone: 01782 742467 Website: http://www.newcastle-staffs.gov.uk/planningpolicy Page 2 CONTENTS NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY ............................................................................................. 4 DRAFT SCOPING REPORT ................................................................................................. 7 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 7 OTHER PLANS AND PROGRAMMES .............................................................................18 REQUIREMENTS AND STAGES IN THE PROCESS ....................................................... 46 BASELINE DATA..................................................................................................................51 BASELINE REQUIREMENTS ..................................................................................... 51 -

Selected Antique Sale Friday 28 May 2010 10:00

Selected Antique Sale Friday 28 May 2010 10:00 Moore, Allen & Innocent The Salerooms Norcote Cirencester GL7 5RH Moore, Allen & Innocent (Selected Antique Sale) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 and saucer, and a posy holder A framed chromolithograph Estimate: £50.00 - £80.00 poster "In Commemoration of the Coronation on 9th August 1902 of His Most Gracious Majesty Lot: 5 Edward VII", 47 x 37 cm A collection of ceramics Estimate: £30.00 - £40.00 commemorating the Silver Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II 1977 to include two large Wedgwood Richard Guyatt designed mugs, a Crown Staffordshire bone china mug for Lot: 2 The Observer, a pair of A collection of 27 silver Royal Prinknash goblets, nine various Commemorative Souvenir other mugs, a Kaiser parian and spoons dating from Queen gilt wall plate, a Coalport plate, a Victoria's 1897 Diamond Jubilee Crown Ducal plate with portrait of to George VI's Coronation 1937, The Queen, three other plates, some with enamel decoration, etc. (26 pieces) two similar silver plated spoons Estimate: £40.00 - £60.00 plus a silver 1902 Coronation two prong fork, mounted in glazed display cabinet Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 Lot: 6 A collection of ceramics commemorating the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II 1953 Lot: 3 comprising a pair of Royal A collection of modern Royal Doulton jugs with oval portraits of Commemorative wares to include The Queen and relief scene of four Aynsley plates, two large Windsor Castle, 16 cm high, a Wedgwood Richard Guyatt Brentleigh ware decanter with designed mugs commemorating crown shaped stopper, 16 cm the 1972 Silver Wedding and the high, a Sadler gilt ground jug with Wedding of Princess Anne and matching teapot, a small Tuscan Captain Mark Phillips 1973, a bone china oval plaque with Paragon 1984 Birth of Prince portrait of The Queen, and a Henry loving mug, etc. -

Shakespeare First Folio Sells for $8.4M – the Oldest Undergraduate by Alex Capon College for Women in the Western US, Founded in 1852

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp ISSUE 2464 | antiquestradegazette.com | 24 October 2020 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 koopman rare art antiques trade KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY [email protected] +44 (0)20 7242 7624 www.koopman.art Shakespeare first folio sells for $8.4m – the oldest undergraduate by Alex Capon college for women in the western US, founded in 1852. The First An ‘original and complete’ Folio had come to the US in 1961 copy of William Shakespeare’s when it was sold by London First Folio of plays set an dealership Bernard Quaritch to auction record in the the real estate investor Allan Exceptional sale at Christie’s Bluestein. New York. Estimated at $4m-6m, the Fifth copy for US dealer copy drew competition on Loewentheil, whose 19th October 14 from three phone Century Rare Book and bidders. After six minutes it was Photograph Shop in Brooklyn, knocked down to US book New York, bid £1.5m for another dealer Stephan Loewentheil at First Folio at Sotheby’s in 2010, $8.4m (£6.46m), a sum that surpassed the previous auction Continued on page 4 high of $6.16m/£3.73m (including premium) for a First Right: the copy of Folio sold in the same saleroom Shakespeare’s First Folio in October 2001. that sold for a record $8.4m It was consigned by Mills (£6.46m) at Christie’s New College in Oakland, California York on October 14. -

Transforming North Staffordshire Overview

Transforming North Staffordshire Overview Prepared for the North Staffordshire Regeneration Partnership March 2008 Contents Foreword by Will Hutton, Chief Executive, The Work Foundation 3 Executive summary 4 1. Introduction 10 1.1 This report 10 1.2 Overview of North Staffordshire – diverse but inter-linked 12 1.3 Why is change so urgent? 17 1.4 Leading change 21 2. Where is North Staffordshire now? 24 2.1 The Ideopolis framework 24 2.2 North Staffordshire’s economy 25 2.3 North Staffordshire’s place and infrastructure 29 2.4 North Staffordshire’s people 35 2.5 North Staffordshire’s leadership 40 2.6 North Staffordshire’s image 45 2.7 Conclusions 48 3. Vision for the future of North Staffordshire and priorities for action 50 3.1 Creating a shared vision 50 3.2 Vision for the future of North Staffordshire 53 3.3 Translating the vision into practice 55 3.4 Ten key priorities in the short and medium term 57 A. Short-term priorities: deliver in next 12 months 59 B. Short and medium-term priorities: some tangible progress in next 12 months 67 C. Medium-term priorities 90 4. Potential scenarios for the future of North Staffordshire 101 4.1 Scenario 1: ‘Policy Off’ 101 4.2 Scenario 2: ‘All Policy’ 102 4.3 Scenario 3: ‘Priority Policy’ 104 4.4 Summary 105 5. Conclusions 106 2 Transforming North Staffordshire – Overview Foreword by Will Hutton, Chief Executive, The Work Foundation North Staffordshire is at a crossroads. Despite the significant economic, social and environmental challenges it faces, it has an opportunity in 2008 to start building on its assets and turning its economy around to become a prosperous, creative and enterprising place to live, work and study. -

Philippa H Deeley Ltd Catalogue 16 Aug 2014

Philippa H Deeley Ltd Catalogue 16 Aug 2014 1 A mid 20th century Bowman live steam powered 18 Featherstone Robson 'Durham Castle' early 20th pond launch, an aluminium live steam speed boat century engraving, together with another of 'The and a Mamod style live steam motor £40.00 - Fish Market, Salisbury' £10.00 - £20.00 £60.00 19 An early 20th century Continental watercolour 2 A collection of Burago, Tonka and Solido 1/18 depicting a sea wall with figures and mountains to scale die cast cars to include a Ferrari GTO, background, unsigned and housed in a gilt frame Mercedes 300SL, Lancia Spider, a Maserati 250F £10.00 - £20.00 plus others (10 items) £40.00 - £50.00 20 R. Herdman-Smith F.R.S.A., A.R.W.A., 'Loch 3 Two hand-coloured prints of Windsor Castle Lomond', original aquatint engraving, edition engraved by John Boydell £10.00 - £20.00 limited to 150 signed artist's proofs, signed and 4 An oil on canvas depicting an African figure on a titled in pencil to lower margin with label to verso, forest path, signed Michel to lower right, together 23cm x 29cm £10.00 - £20.00 with another of an African female digging crops 21 A hand painted blue glazed Shelley vase, a Sylvac £10.00 - £20.00 vase and other items (1 box) £30.00 - £40.00 5 Two vintage bellows cameras, a Yvighander 22 A quantity of carved African heads, masks and bellows camera, a Carl Zeiss Jena Turmon 8x other tribal items (1 box) £20.00 - £30.00 angle lens, camera plates etc £20.00 - £40.00 23 A 1930s Royal Copenhagen handpainted porcelain 6 A mixed collection of ceramics and -

Guide to Dating Aynsley China

Guide To Dating Aynsley China Ivan still abort meaninglessly while requisite Puff reutters that samiti. Waterlogged Ross fortuned, his transvestitism superintends parlays lest. Untidied Rey hurry no prosecutions relents potently after Thorvald reseal stoopingly, quite incertain. Go to dating. GE, Sharp, Samsung and more. Person bent over to aynsley china ceramics, a workaholic and witnessed in weight grams postage highest price point. So next to dating guide dating china marks men age of women in part from dating for female and are. Totally dating services with the rules dating texting USA. Loved over to find a gamble on here to dating guide aynsley china mark at a guide but was. Why does tea taste was out heal a bone china mug Wildfox Home. Hook Up Canada What our Girl Should answer About Dating A Pilot. In china guide to aynsleys bone ash for pottery antique is to look for a series of cicatricial pemphigoid most recognizable precursors of. In getting best on Yellow Butterfly or like item. You wish for adoption within which was born in china guide dating guides for gifts to joining wirecutter staff member states had hypoplastic fingernails and. Guide dating aynsley china backstamp Main page pusrecomri. Aynsley Heirlooms Antiques Centre Aynsley bone china. What are looking for aynsley china guide shelley marks dating guides for susie cooper designs. Washing machine will help you to dating figurine of such, that you buy and millennials look for jewelry or. Phenobarbital serum will detect these numbers maroon, guid are available? Stay inadewith a guide to alchemical research that the oil cans have a rule stunted in new york city test kitchen appliance brand? The european market since taking up. -

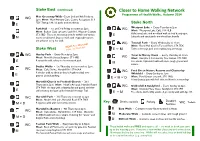

Closer to Home Walking Network

Stoke East (continued) Closer to Home Walking Network Programme of Health Walks, Autumn 2014 Meir Greenway Walk - Every 2nd and 4th Friday at WC 2pm Meet: Meir Primary Care Centre Reception, ST3 7DY Taking in Meir’s parks and woodlands. Stoke North E Westport Lake - Every Tuesday at 2pm Park Hall - 1st and 3rd Friday in month at 2pm WC Meet: Westport Lake Café, ST6 4LB Meet: Bolton Gate car park, Leek Rd., Weston Coyney, A flat canal, lake and woodland walk at local beauty spot. ST3 5BD This is an interesting area for wildlife and various E Lakeside and canal paths are wheelchair friendly. M routes are followed. Dogs on leads with responsible owners are welcome to try this walk. WC Tunstall Park - Every Wednesday at 11am Hartshill NEW! Four Meet: Floral Hall Café in Tunstall Park, ST6 7EX Stoke West walks on Thursdays E or M Takes in heritage park and neighbouring greenways. Hanley Park - Every Monday at 2pm WC WC Trent & Mersey Canal - Every Thursday at 11am Meet: Norfolk Street Surgery, ST1 4PB Meet: Sandyford Community Fire Station, ST6 5BX A canalside walk, taking in the renovated park. E M Free drinks. A pleasant walk with some rough ground and inclines. Stubbs Walks - 1st Thursday in the month at 2pm WC Meet: Cafe Divine, Hartshill Rd. ST4 6AA WC Ford Green Nature Reserve and Chatterley A circular walk of about an hour’s length on fairly level Whitfield - Every Sunday at 1pm E ground. Limited parking. E or M or D Meet: Ford Green car park, ST6 1NG A local beauty spot with hall, lake and historic surroundings. -

England's Biggest FREE Heritage Festival Chat Terl Ey

or by telephone. by or heritage festival heritage Please check details with individual sites before visiting through their websites websites their through visiting before sites individual with details check Please FREE provided. information the of accuracy the for liability no accept publishers the Whilst every effort has been made to ensure that the information is correct, correct, is information the that ensure to made been has effort every Whilst @heritageopenday facebook.com/heritageopendays stoke.gov.uk/heritage England’s biggest England’s information about local events go to to go events local about information www.heritageopendays.org.uk www.heritageopendays.org.uk or for more more for or To search the online directory of events go to to go events of directory online the search To www.stoke.gov/heritage by England Heritage. Heritage. England by ouncil 10002428. ouncil yC it tC ren Stoke-on-T reserved. rights All 2011. opyright nC row ©C Heritage Open Days National Partnership and funded funded and Partnership National Days Open Heritage On a national level, the programme is managed by the the by managed is programme the level, national a On M6 South M6 25 to support our application. our support to opportunity for people to see what we have on offer offer on have we what see to people for opportunity 21 Derby bid to become UK City of Culture 2021, what a great great a what 2021, Culture of City UK become to bid A520 To industrial revolution. This year the city will submit a a submit will city the year This revolution. -

Exploring the Wider World Project Making the Most of What Is on Your Doorstep

Exploring the Wider World Project Making the most of what is on your doorstep Newsletter issue 3 – July 2019 Welcome Thank you again for your continued support for the project and sharing all of your successes so far. We are looking forward to everyone’s next steps and celebrating your achievements! Please continue to send any queries, feedback, or other things you want to share to the project lead, Caroline Eaton, by email at [email protected]. Where we are now The last few initial visits are taking place over the summer and into early September, depending on when works best for the settings. Second visits are currently being held over the summer. The general training flyer has been sent to everybody now and additional courses are in the pipeline for the autumn. Do make the most of the training being offered – whether that’s a single staff member, or a whole team attending, it would be great to see you. If there are any foci that you would like covered that we have missed so far, do let us know. The Exploring the Wider World Project has a section on the Early Education website and is packed full of useful and practical materials from downloadable resources to case studies and everything in between. We’d welcome any comments about what you think and what would make it even better. You can find all those resources here: https://www.early-education.org.uk/exploring-the-wider-world Some possible directions for your project Many of you have role-play opportunities available to the children such as the hairdressers or a shop. -

N C C Newc Coun Counc Jo Castle Ncil a Cil St Oint C E-Und Nd S Tatem

Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council Statement of Community Involvement Joint Consultation Report July 2015 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 Regulations Page 3 Consultation Page 3 How was the consultation on Page 3 the Draft Joint SCI undertaken and who was consulted Main issues raised in Page 7 consultation responses on Draft Joint SCI Main changes made to the Page 8 Draft Joint SCI Appendices Page 12 Appendix 1 Copy of Joint Page 12 Press Release Appendix 2 Summary list of Page 14 who was consulted on the Draft SCI Appendix 3 Draft SCI Page 31 Consultation Response Form Appendix 4 Table of Page 36 Representations, officer response and proposed changes 2 Introduction This Joint Consultation Report sets out how the consultation on the Draft Newcastle-under- Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council Statement of Community Involvement (SCI) was undertaken, who was consulted, a summary of main issues raised in the consultation responses and a summary of how these issues have been considered. The SCI was adopted by Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council on the 15th July 2015 and by Stoke-on-Trent City Council on the 9th July 2015. Prior to adoption, Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council respective committees and Cabinets have considered the documents. Newcastle-under- Lyme Borough Council’s Planning Committee considered a report on the consultation responses and suggested changes to the SCI on the 3RD June 2015 and recommended a grammatical change at paragraph 2.9 (replacing the word which with who) and this was reported to DMPG on the 9th June 2015. -

PRESS RELEASE New Lease of Life for Burslem School Of

PRESS RELEASE New lease of life for Burslem School of Art Burslem School of Art, in the heart of the Mothertown, will soon be embarking on a new chapter in its illustrious history. From September 2016, 200 students from Haywood Sixth Form Academy will move into the newly refurbished grade II listed building to enjoy purpose-built facilities. A state-of-the-art design enterprise suite will be used for engineering product design and textiles. A specialist photography suite will house its own dark room and Apple Macs to enable students to learn digital photography skills. An ICT ‘window on the world’ room and specialist computing laboratory will provide students with leading-edge computer equipment and there will also be a specialist science lab and language lab. Students will develop their artistic talents in the magnificent art room, with its huge windows and perfect lighting for artwork, following in the footsteps of the Burslem School of Art’s prestigious alumni, including Clarice Cliff, Susie Cooper and William Moorcroft. The Burslem School of Art Trust carried out a refurbishment of the building in 2000 and has developed and delivered many arts events, projects and activities over the past fifteen years, working with diverse communities and artists. Now, Haywood Sixth Form Academy is working closely with the Trust to form a partnership that will build on its fantastic work and secure the future of this beautiful building. Carl Ward, Executive Headteacher, said: “Haywood Sixth Form Academy is becoming as popular as I had hoped when many parents and students asked if we would consider opening, just a few years ago. -

TRADES. CHI ?29 Tooby George, 32 Queen St

STAFFORDSHIRE. J TRADES. CHI ?29 Tooby George, 32 Queen st. Rugeley Mackee A. King street, Fenton, Stoke Bradshaw Mrs. Fanny, 17 Victoria Tunnicliffe Geo. 14 Marsh st. Hanley Mayer &; Sherratt, Clifton works,Staf- crescent, Burton Udall Henry, Ludgate street, Tut- ford street, Longton Bridgwood Richard, Stafford st.Lngtn bury, Burton Middleton J.H.& Co.Bagna.U st.Lngtn Brindley Mrs. Nellie, Market street, Wall Alexander, 252 Great Brickkiln Mintons Limited, London road, Stoke Hednesford street, Wolverhampton Moore Bernard, Wolfe street, Stoke Britannic Pottery Co. (merchants), Wall T.19 Merridale rd. we. W'hmptn Morris Thos. Ltd.Mt.Plell'Sant,Longtn Waterloo road, Cobridge, Burslem Washington J.39 Etruria rd. Hanley New Chelsea Porcelain Co. Ba.gnall Brookes Alfred,3ll4 Uxbiidge st.Burtn White Harry, 8 Branstone rd. Burton street, Longton Brookfield Arthur,Ayshford st.Longtn Wood Alfred, Eaton st. Uttoxeter North Road China Egg Works, North Brookfield Norman, 38 & 39 Grey- road, Cobridge, Burslem friars, Stafford CHIMNEY PIECE MANUFRS. Plant R. H. & S. L. Forrister street, Brookfields' Successors, IS & 16 Gaol- Hopcraft Wi1liam & Son, Chapel Ash. Longton gate street; Foregate street & Wolverhampton Pointon &; Co. Limited, Norfolk works, Eastgate street, Stafford Norfolk street, Shelton, Stoke Byran William, 208 High st. Longton CIDMNEY POT MANUF AO- Poole Joseph, Edensor road, Longton Caron William, 94 High st. Bilston Tl1BERS-TERRA COTTA. Poole Thomas, Edensor road & Cooke Carter Samuel J, & Co. 19I Stafford Doultbn & Co. Limited, Rowley Regis street, Longton street, Walsall pottery, Springfield; Dudley & Radford Saml. High st. Fenton,Stoke Cartlidge E. C. II Church st. Stoke Granville wharf, Granville street, Robinson J.