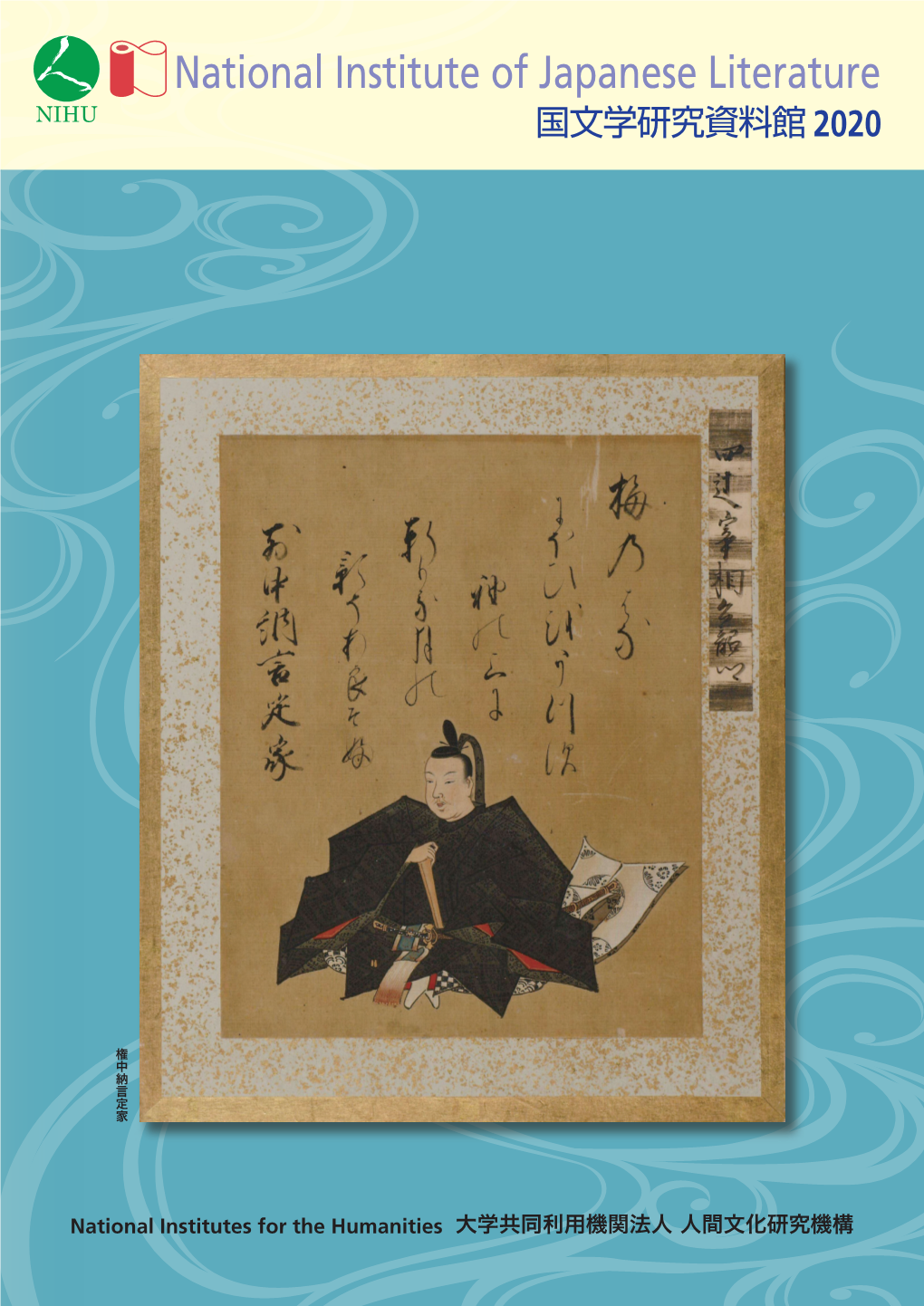

National Institute of Japanese Literature NIHU 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iseas 4001-7574 (Pdf)

DENOMINAZIONE DESCRITTIVA No. CONDIZIONE E COLLOCAMENTO DEGLI OGGETTI Seraphin Couvreur, Les Annalis de la Chine, cathasia, 1950. 4001 Georges Margoulies, Me "Fou" dans le Wen Siuan, Paul 4002 Ceuthner, 1926. Francois MacŽ, La mort et les funerailles, Pub. Orientalistes 4003 France, 1986. Seraphin Couvreur, LIKI: Memories sur les Bienseances et les 4004 ceremonies vol. 1, Cathasia, 1950. Seraphin Couvreur, LIKI: Memories sur les Bienseances et les 4005 ceremonies vol. 2, Cathasia, 1950. Seraphin Couvreur, LIKI: Memories sur les Bienseances et les 4006 ceremonies vol. 3, Cathasia, 1950. Seraphin Couvreur, LIKI: Memories sur les Bienseances et les 4007 ceremonies vol. 4, Cathasia, 1950. Andre Levy, Inventaire Analytique et Critique dei Conte Chinois 4008 Langue Vulgaire vol. VIII, College de France, 1978. Andre Levy, Inventaire Analytique et Critique dei Conte Chinois 4009 Langue Vulgaire vol. VIII-2, College de France, 1978. Andre Levy, Inventaire Analytique et Critique dei Conte Chinois 4010 Langue Vulgaire vol. VIII-3, College de France, 1978. Max Kaltenmark, Le Lie-Sien Tchouan, College de Francd, 4011 1987. Seraphin Couvereur, Tch'ouen Ts'iou et Tso Tchouan: La 4012 Chronique de la Principaute de L™u vol. 1, Cathasia, 1951. Seraphin Couvereur, Tch'ouen Ts'iou et Tso Tchouan: La 4013 Chronique de la Principaute de L™u vol. 2, Cathasia, 1951. Seraphin Couvereur, Tch'ouen Ts'iou et Tso Tchouan: La 4014 Chronique de la Principaute de L™u vol. 3, Cathasia, 1951. Remi Mathieu, Anthologie des Mythes et Legendes de la Chine 4015 ancienne, Gallimard, 1989. Shang Yang, Le Livre de Prince Shang Flammarion, 1981. 4016 J-J-L. -

The Discourse on the “Land of Kami” (Shinkoku) in Medieval Japan National Consciousness and International Awareness

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1996 2 3/3-4 The Discourse on the “Land of Kami” (Shinkoku) in Medieval Japan National Consciousness and International Awareness Kuroda Toshio Translated by Fabio Rambelli This essay examines the concept of “shinkoku” (land of the kami) as it evolved in medieval Japan, and the part this concept played in the devel opment of a state ideology. A close look at medieval documents reveals that medieval Shinto doctrines arose in Japan as part of the exoteric-esoteric sys tem (kenmitsu taisei),the dominant politico-religious ethos of the times, and was heavily influenced by the Buddhist teaching of original enlight enment (hongaku shiso). In this sense it was a construct of Buddhism, and a reactionary phenomenon arising out of the decadence of the earlier system of government rule. The exo-esoteric system (kenmitsu taisei 顕密体制)was,as I have dis cussed in other writings, inseparably related to the medieval Japanese state. How, then, did kenmitsu thought influence the contemporane ous awareness oi the Japanese state and of the world outside Japan? I would like to investigate this question in the present essay through an analysis of the medieval discourse on the “land of the kami” (shinkoku ネ申国). Earlier studies on the shinkoku concept have tended to consider it in isolation rather than in the context of the various historical factors with which it was inseparably linked,factors such as exo-esotericism (kenmitsu shugi II 始、王義 ,the womb or essence of shinkoku thought) and the contemporaneous Japanese attitude toward the world out- This article is a translation of the fourth section, ^Chusei no shinkoku shiso: Kokka ishi- ki to kokusai kankaku,” of Kuroda Toshio’s essay <£Chusei ni okeru kenmitsu taisei no tenkai” (Kuroda 1994). -

ZEN BUDDHISM TODAY -ANNUAL REPORT of the KYOTO ZEN SYMPOSIUM No

Monastic Tradition and Lay Practice from the Perspective of Nantenb6 A Response of Japanese Zen Buddhism to Modernity MICHEL MOHR A !though the political transformations and conflicts that marked the Meiji ..fiRestoration have received much attention, there are still significant gaps in our knowledge of the evolution that affected Japanese Zen Buddhism dur ing the nineteenth century. Simultaneously, from a historical perspective, the current debate about the significance of modernity and modernization shows that the very idea of "modernity" implies often ideologically charged presup positions, which must be taken into account in our review of the Zen Buddhist milieu. Moreover, before we attempt to draw conclusions on the nature of modernization as a whole, it would seem imperative to survey a wider field, especially other religious movements. The purpose of this paper is to provide selected samples of the thought of a Meiji Zen Buddhist leader and to analyze them in terms of the evolution of the Rinzai school from the Tokugawa period to the present. I shall first situ ate Nantenb6 lff:Rtf by looking at his biography, and then examine a reform project he proposed in 1893. This is followed by a considerarion of the nationalist dimension of Nantenb6's thought and his view of lay practice. Owing to space limitations, this study is confined to the example provided by Nantenb6 and his acquaintances and disciples. I must specify that, at this stage, I do not pretend to present new information on this priest. I rely on the published sources, although a lot remains to be done at the level of fun damental research and the gathering of documents. -

Chapter 13: the Second Phase of Kosen-Rufu and the Temple Issue

CHAPTER 13 The Second Phase of Kosen-rufu and the Temple Issue When Josei Toda died in , many critics in the Japanese media were confident that the Soka Gakkai would not sur- vive without his leadership. In- stead, the Gakkai remained Daisaku Ikeda’s united under the leadership of Global Leadership Daisaku Ikeda, who was then chief of staff. On May , ,he became the third president of the Soka Gakkai. Inheriting his mentor’s will to spread Nichiren Daisho- nin’s Buddhism both far and wide, President Ikeda brought about unprecedented growth on a global scale. In October 1960, soon after his inauguration, he visited North and South America. The following year he traveled to India, ac- companied by Nittatsu, the sixty-sixth high priest. Ikeda traveled around the globe—to the Americas, Europe and Asia, including China and the former Soviet Union. Through those visits, he encouraged and nurtured the faith of those living outside Japan while promoting peace, culture and education based on the Daishonin’s Buddhism. By he had visited fifty-four nations. 139 THE UNTOLD HISTORY OF THE FUJI SCHOOL In January , the First International Buddhist League World Peace Conference was held in Guam. On that occa- sion, what later was named the Soka Gakkai International was formed, and Ikeda became its first president. Under his leadership the SGI continued to develop. As of , about ,, members were practicing the Daishonin’s Bud- dhism in countries and territories outside Japan, con- tributing to their respective communities and nations. In his writings, the Daishonin expresses his hope for the global spread of his teachings. -

CAMEO Conflict and Mediation Event Observations Event and Actor Codebook

CAMEO Conflict and Mediation Event Observations Event and Actor Codebook Event Data Project Department of Political Science Pennsylvania State University Pond Laboratory University Park, PA 16802 http://eventdata.psu.edu/ Philip A. Schrodt (Project Director): < schrodt@psu:edu > (+1)814.863.8978 Version: 1.1b3 March 2012 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.0.1 Events . .1 1.0.2 Actors . .4 2 VERB CODEBOOK 6 2.1 MAKE PUBLIC STATEMENT . .6 2.2 APPEAL . .9 2.3 EXPRESS INTENT TO COOPERATE . 18 2.4 CONSULT . 28 2.5 ENGAGE IN DIPLOMATIC COOPERATION . 31 2.6 ENGAGE IN MATERIAL COOPERATION . 33 2.7 PROVIDE AID . 35 2.8 YIELD . 37 2.9 INVESTIGATE . 43 2.10 DEMAND . 45 2.11 DISAPPROVE . 52 2.12 REJECT . 55 2.13 THREATEN . 61 2.14 PROTEST . 66 2.15 EXHIBIT MILITARY POSTURE . 73 2.16 REDUCE RELATIONS . 74 2.17 COERCE . 77 2.18 ASSAULT . 80 2.19 FIGHT . 84 2.20 ENGAGE IN UNCONVENTIONAL MASS VIOLENCE . 87 3 ACTOR CODEBOOK 89 3.1 HIERARCHICAL RULES OF CODING . 90 3.1.1 Domestic or International? . 91 3.1.2 Domestic Region . 91 3.1.3 Primary Role Code . 91 3.1.4 Party or Speciality (Primary Role Code) . 94 3.1.5 Ethnicity and Religion . 94 3.1.6 Secondary Role Code (and/or Tertiary) . 94 3.1.7 Specialty (Secondary Role Code) . 95 3.1.8 Organization Code . 95 3.1.9 International Codes . 95 i CONTENTS ii 3.2 OTHER RULES AND FORMATS . 102 3.2.1 Date Restrictions . 102 3.2.2 Actors and Agents . -

"The Sin of Slandering the True Dharma in Nichiren's Thought" (2012)

ll2 JAMES C. DOBBINS Takase Taisen i%1J!ii:kl[. "Shinran no Ajase kan"' ®.ll!'0fi'Trl!'l"tl!:1ll!. IndogakuBukkyiigaku kenkyii. f'Di3!:${bllit'J!:liJIJ'l; 52.1 (December zoos): 68-70. YataRyOshO fk.IE TiJ. "Kakunyo ni okeruakuninshOkisetsuno tenkai" W:ftDIZ:.:f31t 0~ AlEjjj!Jm(l) ,!llr,::J. In Sh;nrGJl kyiifb_aku no shomondai ®.ll!'W1$0ll1\'Po~l1!l, ed. RyUkoku THE SIN OF "SLANDERING THE TRUE DHARMA'' Daigaku Shinshil Gakkai -~~~j;;:TJ4**~· Kyoto: Nagata Bunshodo, 1987. IN NICHIREN'S THOUGHT "Rennyo ni okeru akunin sh6ki setsu no tenkai" l!li'ftof;::JOft o!!,!;AlEjjj\Jm0,!llr,::J. lnRemryo taike; l!l'ftD{21<:*, voL z., ed. KakehashiJitsuen i!f;)!(~ eta!. Kyoto: Hozokan, 1996. Jacqueline I. Stone "Zonkaku ni okeru akunin sh6ki setsu no tenkai" i'¥fto f;::jO It{\ Jl,!;AlE#li1m0 MIJH. Shinshilgaku J)J;fi<$ 77 (February 1988): 12-13. In considering the category of ''sin" in comparative perspective, certain acts, such as murder and· theft, appear with some local variation to be proscribed across traditions. Other offenses, while perhaps not deemed such by the researcher's own cuJture, nonetheless fa!J into recognizable categories of moral and ritual transgression, such as failures of filial piety or violations of pnrity taboos. Some acts characterized as wrongdoing, however, are so specific to a particular historical or cognitive context as to require an active exercise of imagination on the scholar's part to reconstruct the hermeneutical framework within which they have been abhorred and condemned. Such is the case with the medieval Japanese · Buddhist figure Nichiren B:il (1222-1282) and his fierce opposition to the sin of "slandering the True Dharma" (hihO shi5bi5 ~lwHE$, or sim ply hobo lW$). -

Accounts of High Priest Nichikan

Index A Abe, Houn, see Nichikai Aburano Joren, 31 “Accounts of High Priest Nichikan, The,” 70 “Accounts of Teacher Nichiu,The,” 32 agrarian reform, 127 Akiya, Einosuke, 159, 171 Amida Buddha, 28, 48 “Articles Regarding the Succession of Nikko,” 22, 38, 39 Association for the Reformation of Nichiren Shoshu, 172 Association of Youthful Priests Dedicated to the Reformation of Nichiren Shoshu, 172 Atsuhara Persecution, 14; three martyrs, 14 Aum Supreme Truth sect, 164 Avalokiteshvara, 36 B Bennaku Kanjin Sho, see Dispelling Illusion and Observing One’s Mind Bodhisattva Jizo, 28 Bodhisattvas of the Earth, 208 Buddha, of absolute freedom, 75; of the Latter Day, 42; power of the, 77 Buddhahood, attainment is not decided by externals, 11; see also enlightenment Buddhism, as a means for economic gain, 161; funeral Buddhism, 56; of sowing, 73 bureau of religious affairs, 103 C celibacy (of priesthood) renounced, 91–95; see also priesthood 219 220 THE UNTOLD HISTORY OF THE FUJI SCHOOL ceremonial formalities, 42 Chijo-in, 86 Christianity, 55, 56, 84, 110 Chronology of Nichiren Shoshu and the Fuji School,The, 182 Chronology of the Fuji School,The, 47 Collected Essential Writings of the Fuji School,The, 4 Collected Writings of Nichiren Daishonin,The, 41, 129 Collection of High Priest Nichikan’s Commentaries,The, 73, 74, 75 Complete Works of High Priest Nichijun, 137, 138 Complete Works of High Priest Nittatsu, 211, 212–13 Complete Works of Josei Toda, 123, 126 Complete Works of the Fuji School, 41 Complete Works of the Nichiren School, 176 Complete -

Winter 2012 • Volume 21 • Issue I Stranger in a Strange Land

Winter 2012 • Volume 21 • Issue I Stranger in a Strange Land Stephen Welch tranger in a Strange Land is the title of a book by science fiction author Robert Heinlein. In the book, an alien named Mike comes to Earth and meets up with a group of people who befriend him. During the course of the book, the alien learns about different human traits such as laughter and sadness. In some ways, I can relate to Mike after stepping off that plane over nine months ago, finding myself in a strange world without really knowing anyone, no friends or family. I can still remember riding on the bus from Narita airport down to Shinjuku being both amazed and terrified at the numerous signs filled with an almost strange pictograph- like language which I couldn’t read. Even the hotel room seemed different. I remem- ber looking at the odd electric water kettle in my room thinking to myself, ”What would people need this for? Is there a constant need for hot, boiling water in Japan?” Actually yeah, apparently there is. But of course, like Mike in his parallel story, I gradually started getting accustomed to Japanese life. I too befriended a group of people, meaning I was no longer a stranger, and yet, I still continued to find myself in a strange land. However, one day, several months after I arrived, I was walking down the street. As I passed by, I remember looking at a woman and a child playing in their driveway. That image triggered some- thing in my brain: I had seen this be- fore. -

Minakata Kumagusu and the British Museum

Minakata Kumagusu and the British Museum MATSUI Ryugo, Professor, Ryukoku University Minakata in the British Museum According to Minakata Fumie (1911–2000), the daughter of Minakata Kumagusu (1867–1941), her father continued to share his memories of the British Museum late into his life. “When I first entered the Library, I found it to be the very place I had always dreamed of going,” [1] Minakata had said. It was on April 10, 1895 that Minakata applied for readership at the British Library, one the world’s largest libraries, then located inside the British Museum in central London [2]. Minakata had been introduced by Charles Hercules Read (1857–1929), Keeper of the Department of British and Mediaeval Antiquities and Ethnography, to the Museum’s Augustus Wollaston Franks (1826–97), Read’s predecessor as Keeper, on September 22, 1893 as a young, learned Japanese scholar able to advise the Museum on the Department’s Oriental collection. Minakata became acquainted with Robert Douglas (1838–1913), the first Keeper of the MATSUI Ryugo, Department of Oriental Books, in October, 1895 and assisted him in Professor, Ryukoku compiling the catalogue of Japanese and Chinese books. The British University Museum thus became the base for Minakata’s academic activities in London. In this Library of his dreams, Minakata embarked on a project to research the rare books unavailable in Japan or elsewhere, work which entailed transcribing books either in whole or in part in an anthology he titled “London Extracts,” or “ Rondon nukigaki (ロンドン抜書).” Minakata had completed around thirty-seven volumes of this work when he was expelled from the Museum, in December 1898, for hitting another reader. -

Art and Archaeology of East and Southeast Asia the LIBRARY OF

Art and Archaeology of East and Southeast Asia THE LIBRARY OF DR. JAN FONTEIN Former Director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Partial catalogue April 2018 The Boston Globe June 28, 2017 Jan Fontein, historian of Asian art and former MFA director, dies at 89 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Dr. Fontein helped install the "Money Tree" in the exhibition "Stories from China's Past" in July 1987. As a boy growing up in the Netherlands, Jan Fontein found his calling as a museum director and art historian when he chanced upon an exhibit of ancient artifacts that animated his imagination. “When I was 8 years old, I was taken to a museum in Holland which focused on Roman antiquities. I have a very vivid recollection of that moment,” he told the Globe in 1985. “I saw a dirty old case filled with flint arrowheads. That sounds dull. But I saw the arrowheads as direct messages to me. I envisioned a battle in all its mad glory.” The arrowheads “were not works of art,” he added. “They were simple, humble objects. But they were a way for me to communicate with the past. That was exciting.” While serving from 1975 to 1987 as director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Dr. Fontein shared his enthusiasm about art and ancient centuries with hundreds of thousands of visitors who poured into the blockbuster shows that the MFA staged. He also ushered the institution into the modern era of museums as cultural marketplaces, overseeing the fund-raising and creation of the I.M. -

IGOJUDICC Inte

CHAPTER 7. KEDS PROJECT ACTOR CODES 144 Code Actor IGOEURSCE Council of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) IGOJUDICC International Criminal Court IGOLEGIPU Inter-Parliamentary Union IGOMEAAEU Arab Economic Unity Council IGOMEAACC Arab Cooperation Council IGOMEAAMF Arab Monetary Fund for Economic and Social Development IGOMEAAMU Arab Maghreb Union IGOMEAARL Arab League IGOMOSDEVIDB Islamic Development Bank IGOMOSOIC Organization of Islamic Conferences (OIC) IGONAFCSS Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CENSAD) IGONON Organization of Non-Aligned Countries IGOOAS Organization of American States IGOPGSGCC Gulf Cooperation Council IGOPKO Peacekeeping force (organization unknown) IGOSAFDEVSAD Southern African Development Community IGOSASSAA South Asian Association IGOSEAASN Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) IGOSEASOT Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty (SEATO) IGOSEADEVADB Asian Development Bank IGOUNO United Nations IGOUNOAGRFAO United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization IGOUNOAIE International Energy Agency IGOUNODEVWBK The World Bank IGOUNOHLHWHO World Health Organization (WHO) IGOUNOHRIHCH United Nations High Commission for Human Rights (OHCHR) IGOUNOIAE International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) IGOUNOJUDICJ International Court of Justice (ICJ) IGOUNOJUDWCT International War Crimes Tribunals IGOUNOKID United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) IGOUNOLABILO International Labor Organization IGOUNOREFHCR United Nations High Commission for Refugees (OHCR) IGOUNOWFP World Food Program IGOWAFDEVWAM West Africa Monetary -

National Institute of Japanese Literature NIHU 2019

National Institute of Japanese Literature NIHU 2019 Monorail head office To Kamikitadai "Tachikawa Shiyakusho" bus stop Tachikawa Tachihi City Hall Station "Tachikawa Gakujutsu Plaza" bus stop LaLaport National Institutes for the Humanities "Saibansho-mae" bus stop TACHIKAWA TACHIHI National Institute of Japanese Literature Tokyo District Court Tachikawa branch National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics Takamatsu Station Local Autonomy College Tama Intercity Monorail JGSDF Tokyo Electric Power Tachikawa Tachikawa Second Legal Garrison Affairs Joint Government Building Tachikawa Police Disaster Medical Station Center IKEA National Showa Kinen Park To Haijima JR Oume Line Tachikawa-Kita Station JR Tachikawa Station To Hachioji JR Chuo Line Tachikawa-Minami Station To Tama Center 後鳥羽院宮内卿 National Institutes for the Humanities 大学共同利用機関法人 人間文化研究機構 https://www.nijl.ac.jp/ Contents A Message from the Director: Dr. Robert Campbell 3 Overview 4 Outline of Current Research Being Conducted at NIJL 6 Project to Build an International Collaborative Research Network for Pre-Modern Japanese Texts 7 Activities Overview 14 International Exchange 23 Graduate Education 25 Databases 26 Researchers 27 Reference Data 29 National Institutes for the Humanities 30 A Message from the Director: Dr. Robert Campbell FY 2019( Heisei 31) began with the announcement of a new era-name, in accordance with the first abdication by a resigning emperor in more than 200 years. This newly-named era of“Reiwa” began a month later, amidst a wide variety of reported opinions regarding the significance of the name being chosen from a classical text original to Japan. As a student of Japanese literature, I was delighted that the new era-name“Reiwa” had been chosen from Volume 5 of the Manyōshū, Japan's oldest poetry anthology, in particular from the Chinese preface to a set of 32 poems on viewing plum- blossoms.