Traffic Enforcement in Europe: Effects, Measures, Needs and Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traffic Safety Resource Guide

TRAFFIC SAFETY RESOURCE GUIDE International Association of Chiefs of Police TRAFFIC SAFETY RESOURCE GUIDE TRAFFIC SAFETY RESOURCE GUIDE Cover Images Credits: National Sheriffs’ Association and the New York State Police Version: December 8, 2017 @ 1100 hrs. Disclaimer: This publication is distributed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in the interest of information exchange. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation or the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The United States Government assumes no liability for its content or use thereof. If trade or manufacturers’ names or products are mentioned, it is because they are considered essential to the object of the publication and should not be construed as an endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF CHIEFS OF POLICE 1 TRAFFIC SAFETY RESOURCE GUIDE TRAFFIC SAFETY RESOURCE GUIDE INTRODUCTION Police officers in the United States today know all too and others who best understand what the key issues are. well how challenging it has become to ensure the safe The IACP has learned anecdotally that police officers movement of traffic on the roadways. Factors such have been known to carry the Guide in their patrol vehicle as distracted driving, both alcohol and drug-impaired trunk, while at the same time, police chiefs use the Guide motorists, an increase in total miles driven, and newly in planning for meetings with their city manager, elected emerging considerations such as autonomous vehicles, officials, and community groups. -

Responders' Manual

PHILIPPINE NATIONAL POLICE MANUAL RESPONDERS’ MANUAL CHAPTER I BACKGROUND GENERAL – The Philippine National Police is mandated to enforce the law, maintain peace and order, protect life and property, ensure public safety with the active support of the community. The patrol elements composed of the foot and mobile patrols are the most ubiquitous members of the force and are synonymous to police presence. They are the ones who almost always arrive first at the scene of the crime in response to calls for police assistance. Being the “First Responders,” it is imperative that patrol officers are able to identify violations of law, bring criminals to justice, collect and preserve pieces of evidence, and assist in the prosecution of offenders. 2. PURPOSE AND SCOPE Purpose - This First Responders Handbook provides guidance for patrol officers and other members of the force who respond to the scene of a disaster or other emergency as enumerated in the succeeding pages. It assists them in establishing on-scene command, formulating a situation estimate, alerting others to the condition of emergency, and guides them what to do and how to do it when faced by specific situations. Scope - The handbook discusses the policies, procedures, measures and safety considerations governing the commitment of police patrols in the interest of public order and safety. The procedure should be applied where possible to offenses and situations listed. A modification of some procedures may be necessary because of particular circumstances, however, most will apply in a majority of cases. 3. THINGS AND EQUIPMENT A MOBILE CAR SHOULD HAVE Radio - exclusive channels, call sign, etc Siren Notebook, pen, etc Megaphone/ PA system Photo equipment Hand cuff Whistle Fingerprint equipment Reports format (Traffic accident report, Tech Inspection Report, etc) j. -

The Effectiveness of Police Accountability Mechanisms and Programs What Works and the Way Ahead

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF POLICE ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS AND PROGRAMS WHAT WORKS AND THE WAY AHEAD August 2020 DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. THE EFFECTIVENESS OF POLICE ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS AND PROGRAMS WHAT WORKS AND THE WAY AHEAD Contract No. AID-OAA-I-13-00032, Task Order No. AID-OAA-TO-14-00041 Cover photo (top left): An Egyptian anti-Mubarak protestor holds up scales of justice in front of riot police. (Credit: Khaled Desouki, Agence France-Presse) Cover photo (top right): Royal Malaysian Police deputy inspector-general looks on as Selangor state police chief points to a journalist during a press conference. (Credit: Mohd Rasfan, Agence France-Presse) Cover photo (bottom left): Indian traffic police officer poses with a body-worn video camera. (Credit: Sam Panthaky, Agence France-Presse) Cover photo (bottom right): Indonesian anti-riot police take position to disperse a mob during an overnight-violent demonstration. (Credit: Bay Ismoyo, Agence France-Presse) DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. ii Acronyms ..................................................................................................................................ii -

Safety Tips & More

#thankatrucker T Trusted IN THE R Responsible Safety Zone™ A Awesome Dedicated to Truck Driver Safety Awareness and Wellness JUNE 2020 n VOLUME 13 n ISSUE NO. 3 N Necessary D Dedicated S Safe R Road Warriors Congratulations to Douglas King, F Frontline Heroes I Indispensable TransForce Driver of the Year! O On the Road for Us V Vital n exceptional driver and an employee that all companies would like to have when it comes to R Respected E Efficient “A his work ethics!” Those words were used by our customer, Fourteenth Avenue Cartage to describe Douglas C Conscientious R Reliable King, our Driver of the Year, who we are proud to feature in this issue of In the Safety Zone.™ E Essential S Selfless Winning the Driver of the Year Award here at TransForce is a big deal. Pitted against thousands of drivers, the competition is fierce. Doug has been with TransForce since 2002 and has been working with Fourteenth TransForce Driver Avenue Cartage since 2005. During Referral Program! those years, he has rarely missed a day and has been accident free. What TransForce needs more good drivers a remarkable achievement. When From left to right: David Broome (President and to fill local, regional and OTR openings. asked what his key to success was, CEO, TransForce Group), Paul Braswell (VP, Field he says he just follows the rules, tries Operations and Recruiting), Doug King (Driver of to stay safe and do everything right. the Year), Kimberly Castagnetta (EVP Marketing and Division President Compliance and Safety), We should all follow his lead. -

Automated Speed Enforcement Pilot Project Evaluation

Automated Speed Enforcement Pilot Project Evaluation Final Report as Submitted to the Legislature Prepared by the Washington Traffic Safety Commission As Required by ESSB 5352, Section 201(2) December 30, 2010 as revised: January 18, 2011 Publication and Contact Information A PDF version of this report is available for download on the Washington Traffic Safety Commission website at: http://www-stage.wtsc.wa.gov/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/01/ASEReport123010.pdf For more information contact: Steve Lind Deputy Director Washington Traffic Safety Commission PO Box 40944 Olympia, WA 98504-0944 Phone: 360.725.9897 Email: [email protected] Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Information Persons with disabilities may request this information be prepared and supplied in alternate formats by calling the Washington Traffic Safety Commission at (360) 725-9898. Persons who are deaf or hard of hearing may call access Washington State Telecommunications Relay Service by dialing 7-1-1 and asking to be connected to (360) 725-9898. [This page intentionally left blank] ii TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY OF TERMS ............................................................................................................ iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ v INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ..................................................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... -

The Road to Smarter Traffic Monitoring with Axis Network Video Solutions

Transportation The road to smarter traffic monitoring with Axis network video solutions. www.axis.com/traffic Bringing you closer By 2025, it’s predicted that every day 6.2 billion private motorized trips will be made in cities worldwide*. That means more roads, more road users to the and even greater pressure to get everyone from A to B, safely and efficiently. It’s a huge challenge for traffic management centers – and a testing time for traffic traffic. monitoring technology. Roads don’t run on guesswork. Together with our partners, we offer Traffic management centers need smart solutions that give you a broader, instant access to accurate, real-time deeper understanding of the traffic information – 24/7. Only then, can situation – in any conditions. you detect incidents early and respond quickly. That’s where Axis traffic monitoring solutions can help. *SOURCE: International Association of Public Transport, 2013 www.uitp.org/news/pics/pdf/PTX21.pdf Traffic | 3 From congestion and stopped vehicles to serious accidents and extreme weather, we understand the challenges you face every day. We know it’s not just important to improve the traffic situation in real time, but also over time. That’s why we’ve developed the right solutions to help you achieve this. With our 30 years of experience, spanning a broad range of industries from retail and transport to education and healthcare, we’ve been able to develop technology that can perform in any condition and bring unique value to each user group. Our traffic monitoring solutions put you at the heart of the action Aware, and help you keep the traffic flowing smoothly – at all times. -

Frustration, Aggression & Road Rage

Always remember that the primary goal in defensive driving is to stay safe and live to drive another day. Frustration, Aggression The context in which frustration occurs Other road users are probably equally and Road Rage can determine both the nature and extent frustrated in traffic, perhaps more so. of our own resulting aggressive behavior. They may not be as prepared for traffic. There are also differences in people’s nat- Frustration occurs when someone or Be courteous and forgiving. Your ural propensities. Some drivers are something impedes your progress toward behavior may serve to reduce their content to mutter curses to themselves a goal. In the driving environment our goal levels of frustration and consequently while others are provoked to physical is to get to our destination as quickly and their levels of aggression and violence. Both personal attributes and as safely as possible. When other road risk-taking, thereby making the traffic situational factors can moderate our users interfere with our progress we environment safer for everyone, aggressive responses. become frustrated. In the driving environ- including you. ment, increases in aggression can have Some experts distinguish between Do not fret over people, conditions and deadly consequences. Frustration can aggressive driving and road rage. things that you cannot control. Choose lead to any or all of the following Aggressive driving is instrumental, that is, your battles wisely and save your aggressive behaviour: it serves to further progress toward a energy and emotions for situations that desired outcome when we are frustrated. Excessive speeding or street racing you can influence. -

Medication Use and Driving Risks by Tammie Lee Demler, BS Pharm, Pharmd

CONTINUING EDUCATION Medication Use and Driving Risks by Tammie Lee Demler, BS Pharm, PharmD pon successful completion of this ar- the influence of alcohol has Useful Websites ticle, pharmacists should be able to: long been accepted as one 1. Identify the key functional ele- of the most important causes ■ www.dot.gov/ or http://www.dot.gov/ ments that are required to ensure of traffic accidents and driv- odapc/ competent, safe driving. ing fatalities. Driving under Website of the U.S. Department of 2. Identify the side effects associated with pre- the influence of alcohol has Transportation, which contains trends Uscription, over-the-counter and herbal medi- been studied not only in ex- and law updates. It also contains an cations that can pose risks to drivers. perimental research, but also excellent search engine. 3. Describe the potential impact of certain medi- in epidemiological road side ■ www.mayoclinic.com/health/herbal- cation classes on driving competence. studies. The effort that society supplements/SA00044 4. Describe the pharmacist’s duty to warn re- has made to take serious le- Website for the Mayo Clinic, with garding medications that have the potential to gal action against those who information about herbal supplements. impair a patient’s driving competence. choose to drink and drive It offers an expert blog for further exploration about specific therapies and 5. Provide counseling points to support safe driv- has resulted in the significant to receive/share insight about personal ing in all patients who are receiving medication. deterrents of negative social driving impairment with herbal drugs. stigma and incarceration. -

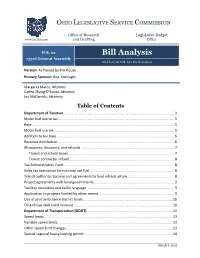

Bill Analysis 133Rd General Assembly Click Here for H.B

OHIO LEGISLATIVE SERVICE COMMISSION Office of Research Legislative Budget www.lsc.ohio.gov and Drafting Office H.B. 62 Bill Analysis 133rd General Assembly Click here for H.B. 62’s Fiscal Analysis Version: As Passed by the House Primary Sponsor: Rep. Oelslager Effective Date: Margaret Marcy, Attorney Carlen Zhang-D’Souza, Attorney Joe McDaniels, Attorney Table of Contents Department of Taxation ................................................................................................................. 3 Motor fuel excise tax ...................................................................................................................... 5 Rate ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Motor fuel use tax ........................................................................................................................... 5 Addition to tax base ........................................................................................................................ 6 Revenue distribution ....................................................................................................................... 6 Allowances, discounts, and refunds ............................................................................................... 7 Transit and school buses ............................................................................................................ 7 Transit contractor refund .......................................................................................................... -

Philippines: Reports of Corruption and Bribery

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 24 August 2006 PHL101564.E Philippines: Reports of corruption and bribery within the police force; government response; frequency of convictions of members of the police force accused of criminal activity (2004 - 2006) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa The Report on the Transparency International Global Corruption Barometer 2004 revealed that Filipinos considered the police to be the most corrupt institution or sector in their country (TI 9 Dec. 2004, 11). The following year, the police dropped to second place in the ranking of corrupt institutions as perceived by the public, behind political parties and the legislature, which tied for first place (ibid. 9 Dec. 2005, 18). Starting in 2000, surveys of efforts made by public and private agencies to combat corruption were conducted by the Quezon City- based non-profit social research organization, Social Weather Stations (SWS n.d.). The results indicated that the Philippine National Police (PNP) received a "bad" rating in 2005, a rating it retained in 2006 (Manila Standard 7 July 2006; The Manila Times 8 July 2006). Both Philippine President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and the chief director of the PNP, Edgar Aglipay, have acknowledged that corruption is a problem within the police force (Philippines 17 July 2003; INQ7 3 Jan. 2005; Manila Standard 11 Dec. 2004). In a 2003 statement, President Arroyo called police corruption a "serious problem" that was negatively affecting national security (Philippines 17 July 2003), while Aglipay remarked that "persistent allegations" of police corruption were contributing to a "crisis of confidence" within the force (INQ7 3 Jan. -

Factors That Impact Driving

LESSON PLAN Factors That Impact Driving NATIONAL HEALTH EDUCATION STANDARDS (NHES) 9-12 Standard 5: Students will analyze the influence of family, peers, culture, media, technology, and other factors on healthy behaviors. • 5.12.2 Determine the value of applying a thoughtful decision-making process in health-related situations. • 5.12.3 Justify when individual or collaborative decision-making is appropriate. • 5.12.4 Generate alternatives to health-related issues or problems. OBJECTIVES Your teen driver education objective is to help students make appropriate driving decisions by first analyzing how various factors impact teen driver safety. Students will achieve this objective by: • Explaining how speed affects teenage driving • Determining the impact of environmental conditions on teenage driving behaviors • Examining the effects of various mental and physical conditions on teenage driving behaviors • Determining the reasons people “take chances” when driving SPEEDING AND DRIVING 1. Have students list different speed limits they encounter while riding or driving in the car. 2. Ask students where they see lower speed limits (residential neighborhoods, etc.) versus where they have seen higher speed limits (highways). 3. Have students discuss the reasons for the variations in speed limits and ask them what might happen if there was just one speed limit, regardless of location. 4. Have students explain the importance of obeying speed limits and the dangers of not obeying speed limits. (cont. on page 2) 1 Do not conduct any activity without adult supervision. This content is provided for informational purposes only. Discovery Education and Toyota assume no liability for your use of the information. Copyright © 2018 Discovery Education. -

Road Rage Factors

ROAD RAGE FACTORS HOW TO AVOID ROAD RAGE Here are some common factors that often Make sure you have the right car insurance policy to contribute to road rage incidents or aggressive protect yourself from aggressive drivers or if you find driving behavior. yourself the victim of a road rage incident. TRAFFIC DELAYS BEFORE YOU GET BEHIND THE WHEEL o Heavy traffic, sitting at stoplights, looking for a o Don’t rush. Give yourself time to get where you’re parking space or even waiting for passengers going; you’re less likely to become impatient and can increase a driver’s anger level. take unnecessary risks. RUNNING LATE o Cool off. If you’re upset, take time to calm down. o Running behind for a meeting or appointment o Be aware and anticipate. If you expect can cause drivers to be impatient. something to happen you can sometimes resolve the issue before it occurs. ANONYMITY o If drivers feel that they probably won’t see WHAT TO REMEMBER WHEN DRIVING other drivers again, they may feel more o Give other drivers a break. If someone is driving comfortable engaging in risky driving slowly, keep in mind they might be lost. behaviors like tailgating, cutting people off, o Use hand gestures wisely. Keep gestures positive - excessive honking or making rude gestures. say, waving to a driver who lets you in when merging. o If the motoring public report these road o Don’t tailgate. Always keep a safe distance from rage incidents to our SEPI office, disciplinary the car in front, no matter how slowly they might measures could be taken with the employee.