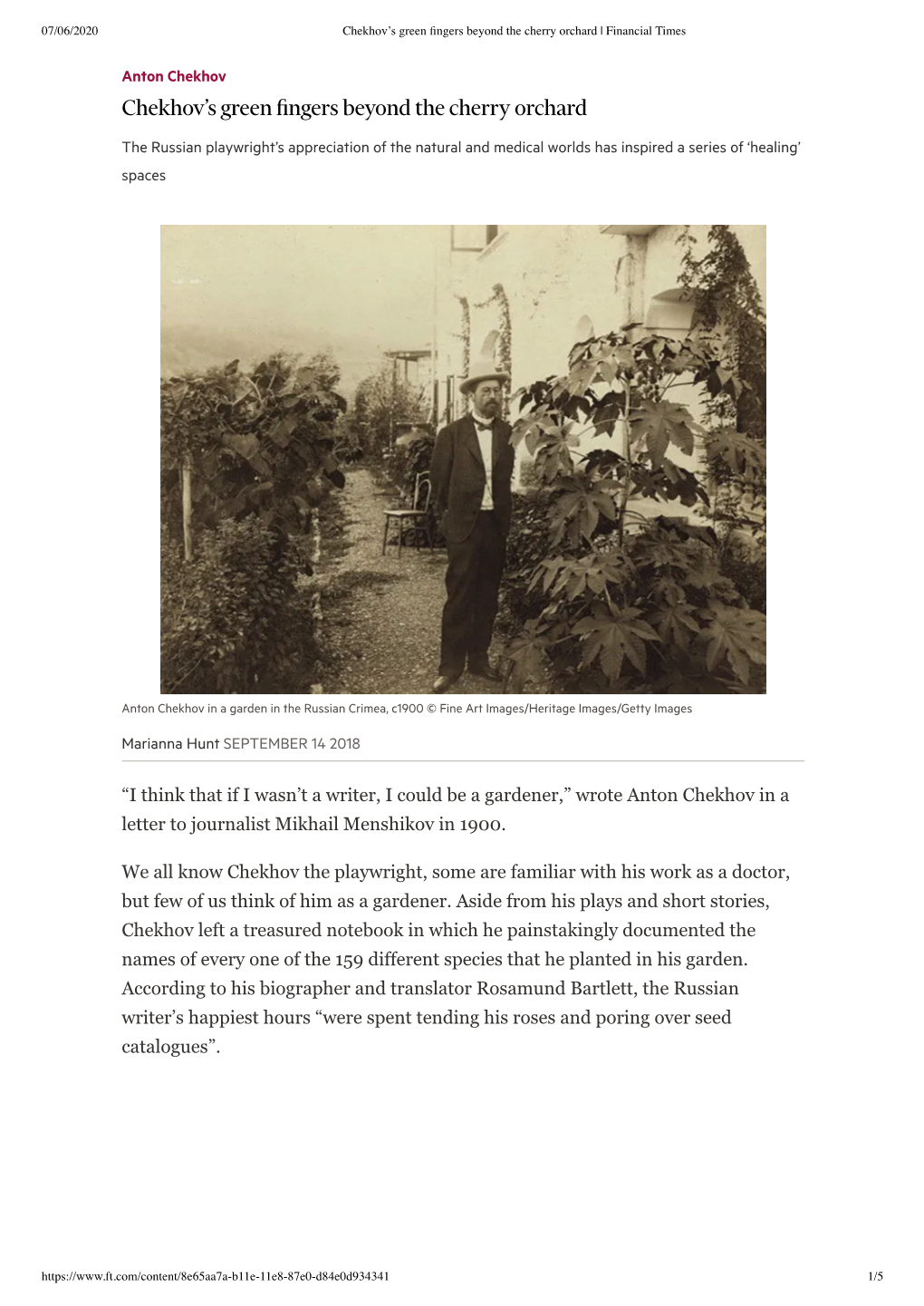

Chekhov's Green Fingers Beyond the Cherry Orchard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cherry Orchard? 13) Touring a Show 14) Activities 15) Glossary 16) Useful Resources 17) Evaluation Form

Blackeyed Theatre and South Hill Park Arts Centre Present Education Pack CONTENTS 1) Welcome 2) The Company – All About Blackeyed Theatre 3) The Team – Who is making the play? 4) The Cast 5) The Play – Synopsis 6) The Author- Anton Chekov 7) The Original Play 8) A statement by the Director 9) Character Breakdown 10) Themes and Context 11) The Practitioner – Constantin Stanislavski and the Moscow Art theatre 12) The Question – How do you do The Cherry Orchard? 13) Touring a show 14) Activities 15) Glossary 16) Useful Resources 17) Evaluation form WELCOME… To The Cherry Orchard Education Pack. Here at South Hill Park we’re very excited about working once again with Blackeyed Theatre, particularly on this exciting and ambitious re-imagining of one of the classic plays of the twentieth century. The following pages have been designed to support study leading up to and after your visit to see the production. The Cherry Orchard will give you a lot to talk about, so this pack aims to supply thoughts and facts that can serve as discussion starters, handouts and practical activity ideas. It provides an insight into the theatrical process of creating and touring a show and is intended to give you and your students an understanding of the creative considerations the team has undertaken throughout the rehearsal process. If you have any comments or questions regarding this pack please email me at [email protected] . I hope you will enjoy the unique experience that this show offers enormously . See you there! Jo Wright, Education and Outreach Officer, South Hill Park Arts Centre THE COMPANY Blackeyed Theatre Blackeyed Theatre Company was established in 2004 to create exciting opportunities for artists and audiences alike. -

Department of Russian and Slavonic Studies 2016-17 Module Name Chekhov Module Id (To Be Confirmed) RUS4?? Course Year JS

Department of Russian and Slavonic Studies 2016-17 Module Name Chekhov Module Id (to be confirmed) RUS4?? Course Year JS TSM,SH SS TSM, SH Optional/Mandatory Optional Semester(s) MT Contact hour per week 2 contact hours/week; total 22 hours Private study (hours per week) 100 hours Lecturer(s) Justin Doherty ECTs 10 ECTs Aims This module surveys Chekhov’s writing in both short-story and dramatic forms. While some texts from Chekhov’s early period will be included, the focus will be on works from the later 1880s, 1890s and early 1900s. Attention will be given to the social and historical circumstances which form the background to Chekhov’s writings, as well as to major influences on Chekhov’s writing, notably Tolstoy. In examining Chekhov’s major plays, we will also look closely at Chekhov’s involvement with the Moscow Arts Theatre and theatre director and actor Konstantin Stanislavsky. Set texts will include: 1. Short stories ‘Rural’ narratives: ‘Steppe’, ‘Peasants’, ‘In the Ravine’ Psychological stories: ‘Ward No 6’, ‘The Black Monk’, ‘The Bishop’, ‘A Boring Story’ Stories of gentry life: ‘House with a Mezzanine’, ‘The Duel’, ‘Ariadna’ Provincial stories: ‘My Life’, ‘Ionych’, ‘Anna on the Neck’, ‘The Man in a Case’ Late ‘optimistic’ stories: ‘The Lady with the Dog’, ‘The Bride’ 2. Plays The Seagull Uncle Vanya Three Sisters The Cherry Orchard Note on editions: for the stories, I recommend the Everyman edition, The Chekhov Omnibus: Selected Stories, tr. Constance Garnett, revised by Donald Rayfield, London: J. M. Dent, 1994. There are numerous other translations e.g. -

FULL LIST of WINNERS the 8Th International Children's Art Contest

FULL LIST of WINNERS The 8th International Children's Art Contest "Anton Chekhov and Heroes of his Works" GRAND PRIZE Margarita Vitinchuk, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “The Lucky One” Age Group: 14-17 years olds 1st place awards: Anna Lavrinenko, aged 14 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Ward No. 6” Xenia Grishina, aged 16 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chameleon” Hei Yiu Lo, aged 17 Hongkong for “The Wedding” Anastasia Valchuk, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Ward Number 6” Yekaterina Kharagezova, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Portrait of Anton Chekhov” Yulia Kovalevskaya, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Oversalted” Valeria Medvedeva, aged 15 Serov, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia for “Melancholy” Maria Pelikhova, aged 15 Penza, Russia for “Ward Number 6” 1 2nd place awards: Anna Pratsyuk, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “Fat and Thin” Maria Markevich, aged 14 Gomel, Byelorussia for “An Important Conversation” Yekaterina Kovaleva, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “The Man in the Case” Anastasia Dolgova, aged 15 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Happiness” Tatiana Stepanova, aged 16 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Kids” Katya Goncharova, aged 14 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chekhov Reading Out His Stories” Yiu Yan Poon, aged 16 Hongkong for “Woman’s World” 3rd place awards: Alexander Ovsienko, aged 14 Taganrog, Russia for “A Hunting Accident” Yelena Kapina, aged 14 Penza, Russia for “About Love” Yelizaveta Serbina, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Chameleon” Yekaterina Dolgopolova, aged 16 Sovetsk, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia for “The Black Monk” Yelena Tyutneva, aged 15 Sayansk, Irkutsk Oblast, Russia for “Fedyushka and Kashtanka” Daria Novikova, aged 14 Smolensk, Russia for “The Man in a Case” 2 Masha Chizhova, aged 15 Gatchina, Russia for “Ward No. -

EDUCATION PACK 1 Bristol Old Vic | the Cherry Orchard | Education Pack “A Poem About Life and Death and Transition and Change” PETER BROOK, 1981

EDUCATION PACK 1 Bristol Old Vic | The Cherry Orchard | Education Pack “A poem about life and death and transition and change” PETER BROOK, 1981 FOREWORD CONTENTS The Cherry Orchard was written over a hundred 2. Introduction years ago and the dominant issue of anxiety and 3. Chekhov, A History change are still with us in a tumultuous twenty-first century. As teachers, we are in a position where we 5. Exploring the Story can challenge ideas and stimulate discussion within 7. Dissecting the Characters our classrooms while exploring a wide range of performance opportunities. This is a play where 9. A Note from the Director seemingly very little happens on stage but events of 11. A Note from the Designer rapid economic and cultural change are happening all around. We know the old way of life is doomed 13. The Moscow Arts Theatre but are not sure whether the new dawn will 14. Under the Microscope ultimately be any better than that which is being cast aside. 15. Key Themes This is a play of many contradictions and is wide 16. How to Write a Review open to a director’s interpretation. Does the future 17. Activities look bleak or alluring? Chekhov wrote The Cherry Orchard while he was dying and knew that this would be his last play. Does this create an air of melancholy? How does this sit with the conjuring tricks and circus skills in this self-declared ‘comedy in four acts’? Is it a naturalistic or symbolic play or a combination of the two? We can decide on any one or all of these interpretations and each are as Introduction valid as any other. -

The Cherry Orchard

The Milwaukee Repertory Theater Presents THE CHERRY ORCHARD BY ANTON CHEKHOV APRIL 17 - MAY 10, 2009 A STUDY GUIDE FOR STUDENTS AND EDUCATORS This study guide is researched and designed by the Education Department at the Milwaukee Repertory Theater and is intended to prepare you for your visit. It contains information that will deepen your understanding of, and appreciation for, the production. We‟ve also included questions and activities for you to explore before and after our performance of THE CHERRY ORCHARD Study Guide Inside This Guide If you would like to schedule a Created By classroom workshop, or if we can Janine Bannier, Synopsis/About the help in any other way, please contact: 2 Education Intern Author and Jenny Kostreva at (414) 290-5370 Historical Context 3 Rebecca Witt, [email protected] Education Who’s Who 4 Coordinator Rebecca Witt at (414) 290-5393 [email protected] An Interview with 5 Edited By Ben Barnes Jenny Kostreva, Education Director Glossary of Terms/ 6 Kristin Crouch, Themes Literary Director Visiting The Rep 8 Page 2 Synopsis THE CHERRY ORCHARD is the story of Madame Ranevskaya, her family and their cherry orchard estate in Russia. The play opens in May, with everyone awaiting the return of Madame Ranevskaya and her daughter Anya from Paris. When they arrive there is much talk of love and happiness between the family members. Unfortunately, the homecoming is not completely happy. Madame Ranevskaya is now in debt and neither she nor her brother, Gayev, have money to pay the mortgage on the estate. If they are unable to pay for the estate by August, it will be auctioned off. -

Week I. Chekhov on His Play

Unfortunately, Chekhov’s innovations were well received by neither directors nor theatergoers. Nor did they receive proper treatment from critics. Chekhov always insisted that he created cheerful, funny short stories and dramas, while critics labeled him a creator of dismal works: “Chekhov’s play makes a hard, if not to say, oppressive impression on the audience” (Sochineniia 13: 449; trans. John Holman); “Three Sisters appears to be a heavy stone on one’s soul” (13: 449; trans. John Holman); “I do not know another work that could ‘infect’ one with such a heavy, obsessive feeling” (13: 449; trans. John Holman). That Chekhov intended his work to be seen as a farce has not yet received a comprehensive evaluation. His first comedy, The Seagull, failed. And no wonder! Spectators who anticipated vaudevillian scenes became extremely angry with the dramatist for misleading them with the subtitle and for representing, instead, a depressing story that ends with the suicide of a main protagonist. The same fate had befallen The Cherry Orchard, a play that was planned to be a farce (as reflected in Chekhov’s letters to his wife, Olga Knipper). In 1901, he wrote to her: “The next play that I am going to write will definitely be funny, at least by its concept” (Sochineniia 13: 478). Critics accused Chekhov of lacking skill; they naturally did not see anything funny about the distressing plays that Chekhov called comedies. But what happened to Three Sisters was even worse. A struggle for the CNT: conservators and innovators. Just as any other innovator, Chekhov suffered for his pioneering changes of the comedic genre, which he unfortunately never discussed in a more logistical way. -

Download Chekhov Plays the Seagull; Uncle Vanya; Three

CHEKHOV PLAYS THE SEAGULL; UNCLE VANYA; THREE SISTERS; THE CHERRY ORCHARD 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Anton Pavlovich Chekhov | --- | --- | --- | 9780413181602 | --- | --- Five Plays: Ivanov / The Seagull / Uncle Vanya / The Three Sisters / The Cherry Orchard I'm probably going to end up owning two or three copies of these plays, but if you are looking for an easy introduction to Chekhov, I would go with the Senelick. However, at least he is genuine. It talks about the conflicts between people who moves forward with time and those who cling to the old fashioned aristocracy, and the friction of the unforgiving passing of time on these characters. Read more And here is the lachrymose Ranevskaya and the other owners of "The Cherry Orchard," egotistical like children, with the flabbiness of senility. More filters. Doesn't mean it'll restore us, though; it ends up destroying us instead. Yesterday, I met with some city officials regarding a property in It's good to read a book that is more than simple entertainment. He acts like his accomplishments are his own, and has earned rest, even though the people who contributed most to his life get no rest. Feb 04, Daniel Klawitter rated it really liked it. You can slap her cheek and she won't even dare to utter a sigh aloud, the meek slave. I am a Dostoevsky fan solidly, but I recognize Chekhov's beauty. And as the introduction attributes a quote to a Russian director: "Uncle Vanya is an American play," because you have a family gathering for the holidays, bickering, a gunshot, then everyone going off more or less reconciled. -

THE CHERRY ORCHARD by Anton Chekhov

THE CHERRY ORCHARD by Anton Chekhov THE AUTHOR Anton Chekhov (1860-1904) was born into a poor family - his father was a shopkeeper and his grandfather had been a serf - a year before the emancipation of the serfs in 1861. He thus grew up in a country experiencing great changes, including the revolutionary movements that would eventually lead to the overthrow of the Romanov dynasty. At the age of nineteen, Chekhov traveled to Moscow to study medicine, and while he was there, supported himself by writing comic pieces for local magazines. Soon, his writing became so popular that he gave up any thought of a career in medicine. Most of his short stories - the works for which he is most famous - were written while he was in his twenties. As he grew older, however, he turned from comedy to more serious themes. Though his early plays had been dismal failures, he returned to writing for the theater in 1896, and in his final eight years wrote the four plays that established his reputation on the stage - The Seagull, Uncle Vanya, The Three Sisters, and The Cherry Orchard. The last of these was written as he was suffering the final depredations of tuberculosis, from which he died only months after it first reached the stage. Chekhov’s plays were criticized in his own day for their lack of plot. His focus on characterization and atmosphere was little appreciated by his contemporaries, and he feared that his plays could never be produced outside Russia because they partook so strongly of the Russian spirit. -

The Chekhovian Intertext Dialogue with a Classic

The Chekhovian Intertext Dialogue with a Classic n LYUDM il A P A R T S THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PREss • COLUMBus Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Parts, Lyudmila. The Chekhovian intertext : dialogue with a classic / Lyudmila Parts.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–8142–1083–3 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978–0–8142–9162–7 (CD- ROM) 1. Chekhov, Anton Pavlovich, 1860–1904—Influence. 2. Chekhov, Anton Pavlovich, 1860–1904—Criticism and interpretation. 3. Russian literature—20th century—History and criticism. 4. Russian literature—21st century—History and criticism. 5. Russia (Federation)—Intellectual life—1991– 6. Russia (Fed- eration)—Civilization—21st century. I. Title. PG3458.Z8P37 2008 891.72’3—dc22 2007045611 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–0–8142–1083–3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–0–8142–9162–7) The author expresses appreciation to the University Seminars at Columbia Uni- versity for their help in publication. Material in this work was presented to the University Seminar: Slavic History and Culture. Studies of the Harriman Institute Columbia University The Harriman Institute, Columbia University, sponsors the Studies of the Harri- man Institute in the belief that their publication contributes to scholarly research and public understanding. In this way the Institute, while not necessarily endors- ing their conclusions, is pleased to make available the results of some of the research conducted under its auspices. Cover design by Jenny Poff Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Palatino Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. -

The Cherry Orchard by Anton Chekhov

The Cherry Orchard by Anton Chekhov Ebook The Cherry Orchard currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook The Cherry Orchard please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback:::: 64 pages+++Publisher:::: Dover Publications; Reprint edition (January 1, 1991)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 9780486266824+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0486266824+++ASIN:::: 0486266826+++Product Dimensions::::5.5 x 0.2 x 8.2 inches++++++ ISBN10 9780486266824 ISBN13 978-0486266 Download here >> Description: The Cherry Orchard was first produced by the Moscow Art Theatre on Chekhovs last birthday, January 17, 1904. Since that time it has become one of the most critically admired and performed plays in the Western world, a high comedy whose principal theme, the passing of the old semifeudal order, is symbolized in the sale of the cherry orchard owned by Madame Ranevsky.The play also functions as a magnificent showcase for Chekhovs acute observations of his characters foibles and for quizzical ruminations on the approaching dissolution of the world of the Russian aristocracy and life as it was lived on their great country estates. While the subject and the characters of the work are, in a sense, timeless, the dramatic technique of the play was a Chekhovian innovation. In this and other plays he developed the concept of indirect action, in which the dramatic action takes place off stage and the significance of the play revolves around the reactions of the characters to those unseen events.Reprinted from a standard edition, this inexpensive well-made volume invites any lover of theater or great literature to enter the world of Madame Ranevsky, Anya, Gayef, Lopakhin, Firs, and the other memorable characters whose hopes, fears, loves, and general humanity are so brilliantly depicted in this landmark of world drama. -

The Cherry Orchard Can Be Downloaded At

Cover 10/5/04 10:58 AM Page 1 KING LEAR HEARTBREAK HOUSE LONG D BOYS FROM SYRACUSE EXIT THE KING M EBUGS THE WILD DUCK GHOSTS A DOLL’S LLECTED WORKS OF BILLY THE KID JUNO E IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST ANATAnton Chekhov I AM A CAMERA THE COCKTAIL PARTY H DSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM MAJOR BARB YBOY OF THE WESTERN WORLD HAPPY D WHAT A LOVELY WAR SCHOOL FOR SCAN NDGAME THE THREEPENNY OPERA TWO TROJAN WOMEN THE GLASS MENAGERIE LOVE FOR LOVE TALES OF THE LOST FOR ORCHARD THE CHERRY INTO THE WOODS SARCOPHAGUS THIRST ONTO MISSISSIPPI JUST BETWEEN OURSCompanion EISBN 0-88865-627-0 MAIDSAnton Pavlovich, 1860-1904. Cherry orchard. 1. Chekhov, Theatre at UBC. 1981-. Amy, Strilchuk, Annie, 1952- IV. I. Durbach, Errol, 1941- II. Marshall, Hallie, 1975- III. Smith, PG3456.V53C5 2004 891.72’3 C2004-905710-3 HAMLET GLACE BAY MINER’SGuide M THE CHERRY ORCHARD by Anton Chekhov translation by Jean-Claude van Itallie directed by STEPHEN HEATLEY set design by CHRISTINA POMANSKI costume design by KAREN MIRFIELD lighting design by HELINA PATIENCE sound design by MICHELLE HARRISON NOVEMBER 4 – 13, 2004 Editors TELUS STUDIO THEATRE Errol Durbach Hallie Marshall Annie Smith Amy Strilchuk Graphic Design James A. Glen Further copies of the Companion Guide to The Cherry Orchard can be downloaded at www.theatre.ubc.ca The Companion Guide to The Cherry Orchard is sponsored by Theatre at UBC In the interest of promoting our creative work and encouraging and generously supported by theatre studies in our community, Theatre at UBC proudly presents The Faculty of Arts this Companion Guide to The Cherry Orchard. -

Brainy Quote ~ Anton Chekhov 002

Brainy Quote ~ Anton Chekhov 002 “Knowledge is of no value unless you put it into practice.” ~ Anton Chekhov 002 ~ Ok "Pengetahuan tidak ada nilainya kecuali Anda mempraktikkannya." ~ Anton Chekhov 002 ~ Ok Berapa lama Anda menempuh Pendidikan? Setidaknya, bila Anda telah lulus SLTA, maka Anda sudah belajar di sekolah formal selama 12 tahun. Bila ditambah dengan usia Anda, jumlah tahun Anda belajar di sepanjang hidup Anda, sudah lebih dari 20 tahun. Apa yang Anda lakukan dengan pengetahuan yang telah Anda miliki? Apakah pengetahuan yang sudah Anda peroleh hanya sekadar informasi yang dikumpulkan? Bila tidak dipraktikan dalam kehidupan nyata, apa manfaatnya pengetahuan tersebut? Seperti quote yang pernah disampaikan oleh Anton Chekhov, seorang penulis berkebangsaan Rusia, hidup dalam rentang tahun 1860-1904 (hanya berusia 44 tahun), ‘Knowledge is of no value unless you put it into practice.’ Secara bebas diterjemahkan, ‘Pengetahuan tidak ada nilainya kecuali Anda mempraktikkannya.’ Pengetahuan baru bernilai dan bermakna, ketika dimanfaatkan dan dipraktikkan dalam kehidupan nyata. Tanpa dilakukan, pengetahuan hanyalah seperti barang-barang yang disimpan digudang, tanpa manfaat. Pengetahuan yang sedikit, namun dilakukan, jauh lebih bermanfaat daripada pengetahuan yang banyak tetapi tidak pernah dipraktikkan. Ada orang yang mengumpulkan banyak ijazah, namun waktu mempraktikannya sangat terbatas atau relatif sedikit. Lalu, kapan investasi waktu dan biaya yang telah dikeluarkan dapat kembali? Bukankah jauh lebih baik, memiliki satu sertifikat saja namun dipraktikkan secara berkesinambungan, sehingga menghasilkan lebih banyak daripada pengorbanan yang telah dilakukan sebelumnya? Praktikkanlah semua pengetahuan Anda. Hanya dengan demikian, ia bernilai guna dan memberi makna. Brainy Quote ~ Anton Chekhov 002 Page 1 Indonesia, 2 Februari 2019 Riset Corporation --- Anton Chekhov Biography.com Playwright, Author (1860–1904) Russian writer Anton Chekhov is recognized as a master of the modern short story and a leading playwright of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.