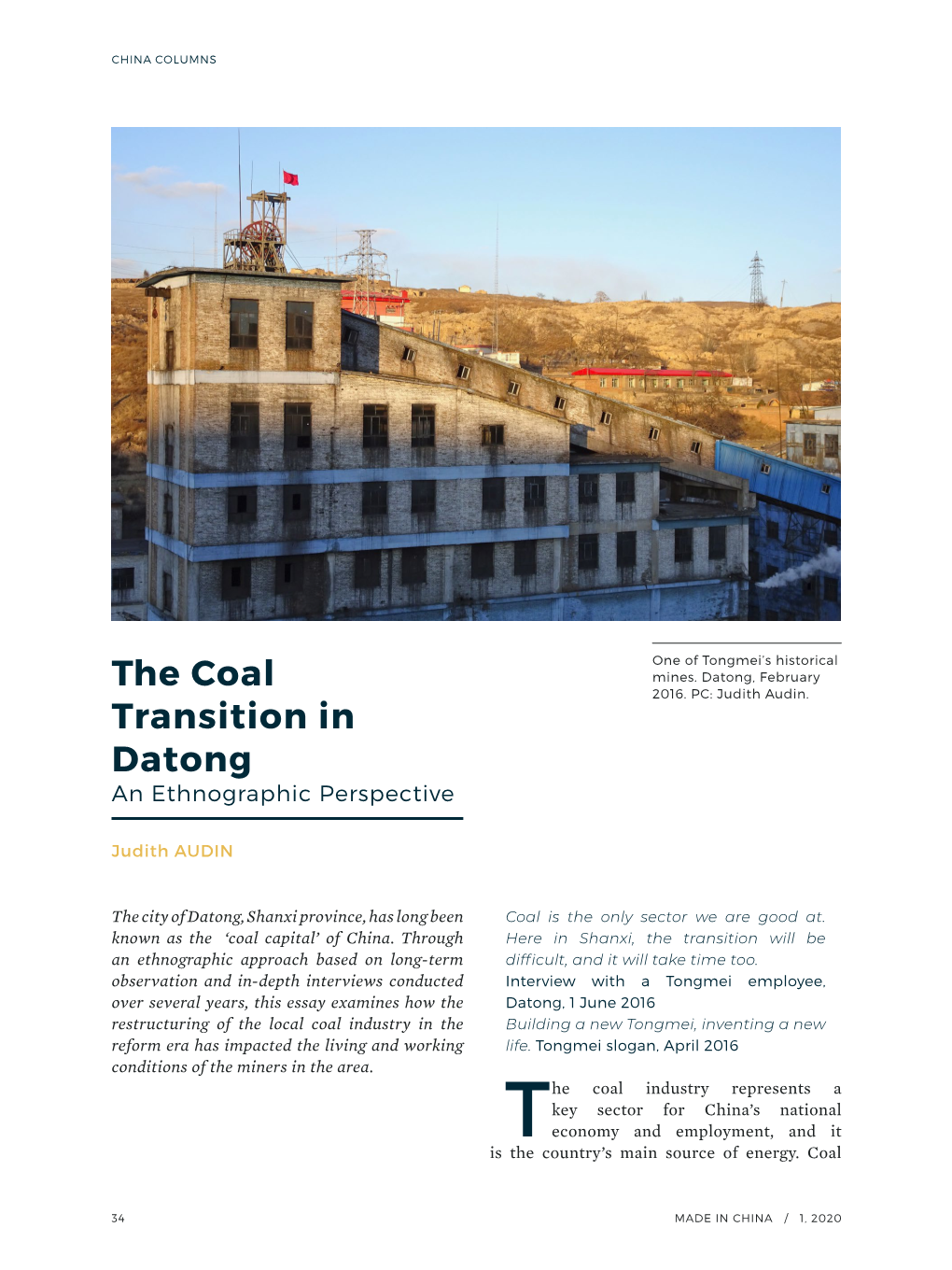

The Coal Transition in Datong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

Based Intervention to Improve Developmental Status

Open access Protocol BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037156 on 19 October 2020. Downloaded from Group- based intervention to improve developmental status among children age 6–18 months in rural Shanxi province, China: a study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial Mengxue Xu,1 Aihua Liu,1 Chunxia Zhao,2 Hai Fang,3 Xiaona Huang,2 Stephen Berman,4 Hongyan Guan 1,5 To cite: Xu M, Liu A, Zhao C, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study et al. Group- based intervention Introduction Early childhood development (ECD) is a to improve developmental critical component for building the foundation of future ► This study fills a gap in the evidence regarding small status among children age physical and emotional health and subsequent academic 6–18 months in rural Shanxi group- based early childhood development (ECD) in- success. The quality of the home environment to promote province, China: a study protocol terventions for at risk rural Chinese children aged development is an important factor in ECD. Since large for a cluster randomised 6–18 months. rural–urban disparities in the home environment exist controlled trial. BMJ Open ► Documenting cost- effectiveness will provide a solid 2020;10:e037156. doi:10.1136/ in China, there is a critical need to develop and evaluate evidence- based foundation for the implementation bmjopen-2020-037156 interventions to promote ECD in rural areas. Individual of future national official recommendations and pol- center- based or home- based interventions dominate ► Prepublication history and icies for ECD in rural China. the current ECD programmes in rural China. -

Environmental Impact Assessment Report

Environmental Impact Assessment Report For Public Disclosure Authorized Changzhi Sustainable Urban Transport Project E2858 v3 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Shanxi Academy of Environmental Sciences Sept, 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized I TABLE OF CONTENT 1. GENERAL ................................................................ ................................ 1.1 P ROJECT BACKGROUND ..............................................................................................1 1.2 B ASIS FOR ASSESSMENT ..............................................................................................2 1.3 P URPOSE OF ASSESSMENT AND GUIDELINES .................................................................4 1.4 P ROJECT CLASSIFICATION ...........................................................................................5 1.5 A SSESSMENT CLASS AND COVERAGE ..........................................................................6 1.6 I DENTIFICATION OF MAJOR ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUE AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS ......8 1.7 A SSESSMENT FOCUS ...................................................................................................1 1.8 A PPLICABLE ASSESSMENT STANDARD ..........................................................................1 1.9 P OLLUTION CONTROL AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION TARGETS .............................5 2. ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE ................................ ................................ 2.1 N ATURAL ENVIRONMENT ............................................................................................3 -

The Effect of Meteorological Variables on the Transmission of Hand, Foot

RESEARCH ARTICLE The Effect of Meteorological Variables on the Transmission of Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease in Four Major Cities of Shanxi Province, China: A Time Series Data Analysis (2009-2013) Junni Wei1*, Alana Hansen2, Qiyong Liu3,4, Yehuan Sun5, Phil Weinstein6, Peng Bi2* 1 Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China, 2 Discipline of Public Health, School of Population Health, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 3 State Key Laboratory for Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control, National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China, 4 Shandong University Climate Change and Health Center, Jinan, Shandong, China, 5 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, Anhui, China, 6 Division of Health Sciences, School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, The University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia OPEN ACCESS * [email protected] (JW); [email protected] (PB) Citation: Wei J, Hansen A, Liu Q, Sun Y, Weinstein P, Bi P (2015) The Effect of Meteorological Variables on the Transmission of Hand, Foot and Mouth Abstract Disease in Four Major Cities of Shanxi Province, China: A Time Series Data Analysis (2009-2013). Increased incidence of hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) has been recognized as a PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9(3): e0003572. doi:10.1371/ journal.pntd.0003572 critical challenge to communicable disease control and public health response. This study aimed to quantify the association between climate variation and notified cases of HFMD in Editor: Rebekah Crockett Kading, Genesis Laboratories, UNITED STATES selected cities of Shanxi Province, and to provide evidence for disease control and preven- tion. -

Due to the Special Circumstances of China Nancy L

Bridgewater Review Volume 5 | Issue 2 Article 6 Nov-1987 Due to the Special Circumstances of China Nancy L. Street Bridgewater State College, [email protected] Recommended Citation Street, Nancy L. (1987). Due to the Special Circumstances of China. Bridgewater Review, 5(2), 7-10. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol5/iss2/6 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. --------------ES SAY-------------- Due To The Special Circumstances ofCHIN1\... BY NANCY LYNCH STREET ,~d Ifim 'h, ,boY< 'id, in 'h, <xch'nge pmgrnm 'On"''' "'''",n Shanxi Teacher's University and Bridgewater State College. I pondered it for awhile, then dropped it. I would find out soon enough the "special circumstances of China." First, I had to get ready to go to China. Ultimately, the context of the phrase would enlighten me. During the academic year 1985-1986 I taught at Shanxi Teacher's University which is located in Linfen, Shanxi Province, People's Republic of China. Like the Chinese, I would soon learn the virtues of quietness and patience. I would listen and look and remember. Perhaps most important of all, I would make friends whom I shall never forget. FROM BE]ING TO LINFEN Cultural Revolution. Seventeen hours by from personal observations here and The Setting train north to Beijing, eight hours south abroad; and finally, from days and weeks The express train arrives in Linfen to Xi'an (home of the clay warriors found of talk and gathering oral history from from Beijing in the early morning, around in the tomb of the Emperor Ching Shi students, colleagues and friends. -

Silk Road Fashion, China. the City and a Gate, the Pass and a Road – Four Components That Make Luoyang the Capital of the Silk Roads Between 1St and 7Th Century AD

https://publications.dainst.org iDAI.publications ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Dies ist ein digitaler Sonderdruck des Beitrags / This is a digital offprint of the article Patrick Wertmann Silk Road Fashion, China. The City and a Gate, the Pass and a Road – Four components that make Luoyang the capital of the Silk Roads between 1st and 7th century AD. The year 2018 aus / from e-Forschungsberichte Ausgabe / Issue Seite / Page 19–37 https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb/2178/6591 • urn:nbn:de:0048-dai-edai-f.2019-0-2178 Verantwortliche Redaktion / Publishing editor Redaktion e-Jahresberichte und e-Forschungsberichte | Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Weitere Informationen unter / For further information see https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb ISSN der Online-Ausgabe / ISSN of the online edition ISSN der gedruckten Ausgabe / ISSN of the printed edition Redaktion und Satz / Annika Busching ([email protected]) Gestalterisches Konzept: Hawemann & Mosch Länderkarten: © 2017 www.mapbox.com ©2019 Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Zentrale, Podbielskiallee 69–71, 14195 Berlin, Tel: +49 30 187711-0 Email: [email protected] / Web: dainst.org Nutzungsbedingungen: Die e-Forschungsberichte 2019-0 des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts stehen unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung – Nicht kommerziell – Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 International. Um eine Kopie dieser Lizenz zu sehen, besuchen Sie bitte http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ -

Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Resources-Based Cities in Shanxi Province Based on Unascertained Measure

sustainability Article Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Resources-Based Cities in Shanxi Province Based on Unascertained Measure Yong-Zhi Chang and Suo-Cheng Dong * Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-64889430; Fax: +86-10-6485-4230 Academic Editor: Marc A. Rosen Received: 31 March 2016; Accepted: 16 June 2016; Published: 22 June 2016 Abstract: An index system is established for evaluating the level of sustainable development of resources-based cities, and each index is calculated based on the unascertained measure model for 11 resources-based cities in Shanxi Province in 2013 from three aspects; namely, economic, social, and resources and environment. The result shows that Taiyuan City enjoys a high level of sustainable development and integrated development of economy, society, and resources and environment. Shuozhou, Changzhi, and Jincheng have basically realized sustainable development. However, Yangquan, Linfen, Lvliang, Datong, Jinzhong, Xinzhou and Yuncheng have a low level of sustainable development and urgently require a transition. Finally, for different cities, we propose different countermeasures to improve the level of sustainable development. Keywords: resources-based cities; sustainable development; unascertained measure; transition 1. Introduction In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) proposed the concept of “sustainable development”. In 1996, the first official reference to “sustainable cities” was raised at the Second United Nations Human Settlements Conference, namely, as being comprised of economic growth, social equity, higher quality of life and better coordination between urban areas and the natural environment [1]. -

CHINA BRIEFING the Practical Application of China Business

CHINA BRIEFING The Practical Application of China Business Business Guide to Central China HEILONGJIANG Harbin Urumqi JILIN Changchun XINJIANG UYGHUR A. R. Shenyang LIAONING INNER MONGOLIABEIJING A. R. GANSU Hohhot HEBEI TIANJIN Shijiazhuang Yinchuan NINGXIA Taiyuan HUI A. R. Jinan Xining SHANXI SHAN- QINGHAI Lanzhou DONG Xi'an Zhengzhou JIANG- SHAANXI HENAN SU TIBET A.R. Hefei Nan- jing SHANGHAI Lhasa ANHUI SICHUAN HUBEI Chengdu Wuhan Hangzhou CHONGQING ZHE- Nanchang JIANG Changsha HUNAN JIANGXIJIANGXI GUIZHOU Fuzhou Guiyang FUJIAN Kunming Taiwan YUNNAN GUANGXI GUANGDONG ZHUANG A. R. Guangzhou Nanning HONG KONG MACAU HAINAN Haikou Featuring the Central Chinese Provinces and Autonomous Regions of Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Inner Mongolia, Jiangxi and Shanxi Including the Mainland Cities of Baotou, Changde, Changsha, Datong, Hohhot, Kaifeng, Luoyang, Manzhouli, Nanchang, Taiyuan, Wuhan, Yichang and Zhengzhou Produced in association with Dezan Shira & Associates Business Guide to Central China Published by: Asia Briefing Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval systems or transmitted in any forms or means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher. Although our editors, analysts, researchers and other contributors try to make the information as accurate as possible, we accept no responsibility for any financial loss or inconvenience sustained by anyone using this guidebook. The information contained herein, including any expression of opinion, analysis, charting or tables, and statistics has been obtained from or is based upon sources believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness. © 2008 Asia Briefing Ltd. Suite 904, 9/F, Wharf T&T Centre, Harbour City 7 Canton Road, Tsimshatsui Kowloon HONG KONG ISBN 978-988-17560-4-6 China Briefing online: www.china-briefing.com "China Briefing" and logo are registered trademarks of Asia Briefing Ltd. -

Activated Carbon from China

SEPARATE-RATE RESPONDENTS PRELIMINARY EXPORTER SUPPLIER DUMPING MARGIN Alashan Yongtai Activated Carbon Co., Ltd., Changji Hongke Activated Carbon Co., Ltd., Datong Forward Beijing Pacific Activated Activated Carbon Co., Ltd., Datong Locomotive Coal & 72.52% Carbon Products Co., Ltd. Chemicals Co., Ltd., Datong Yunguang Chemicals Plant, Ningxia Guanghua Cherishmet Activated Carbon Co., Ltd., Ningxia Luyuangheng Activated Carbon Co., Ltd. Datong Juqiang Activated Datong Juqiang Activated Carbon Co., Ltd., Carbon Co., Ltd. 72.52% Datong Locomotive Coal & Datong Locomotive Coal & Chemicals Co., Ltd. Chemicals Co., Ltd. 72.52% Datong Municipal Yunguang Datong Municipal Yunguang Activated Carbon Co., Ltd. Activated Carbon Co., Ltd. 72.52% Datong Yunguang Chemicals Datong Yunguang Chemicals Plant Plant 72.52% Hebei Foreign Trade and Da Neng Zheng Da Activated Carbon Co., Ltd., Shanxi Advertising Corporation Bluesky Purification Material Co., Ltd. 72.52% Ningxia Guanghua Cherishmet Activated Carbon Ningxia Guanghua Cherishmet Activated Carbon Co., Ltd. 72.52% Co., Ltd. Ningxia Huahui Activated Ningxia Huahui Activated Carbon Co., Ltd. Carbon Co., Ltd. 72.52% Ningxia Mineral & Chemical Ningxia Baota Activated Carbon Co., Ltd. Limited 72.52% China Nuclear Ningxia Activated Carbon Plant, Ningxia Guanghua Activated Carbon Co., Ltd., Shanxi Xinhua Shanxi DMD Corporation Chemical Co., Ltd., Tonghua Xinpeng Activated Carbon 72.52% Factory Actview Carbon Technology Co., Ltd., Datong Forward Activated Carbon Co., Ltd., Datong Tri-Star & Power Shanxi Industry Technology Carbon Plant, Fu Yuan Activated Carbon Co., Ltd., Jing Trading Co., Ltd. 72.52% Mao (Dongguan) Activated Carbon Co., Ltd., Xi Li Activated Carbon Co., Ltd. Datong Forward Activated Carbon Co., Ltd., Ningxia Shanxi Newtime Co., Ltd. Guanghua Chemical Activated Carbon Co., Ltd., Ningxia 72.52% Tianfu Activated Carbon Co., Ltd. -

Transport Corridors and Regional Balance in China: the Case of Coal Trade and Logistics Chengjin Wang, César Ducruet

Transport corridors and regional balance in China: the case of coal trade and logistics Chengjin Wang, César Ducruet To cite this version: Chengjin Wang, César Ducruet. Transport corridors and regional balance in China: the case of coal trade and logistics. Journal of Transport Geography, Elsevier, 2014, 40, pp.3-16. halshs-01069149 HAL Id: halshs-01069149 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01069149 Submitted on 28 Sep 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Transport corridors and regional balance in China: the case of coal trade and logistics Dr. Chengjin WANG Key Laboratory of Regional Sustainable Development Modeling Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China Email: [email protected] Dr. César DUCRUET1 National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) UMR 8504 Géographie-cités F-75006 Paris, France Email: [email protected] Pre-final version of the paper published in Journal of Transport Geography, special issue on “The Changing Landscapes of Transport and Logistics in China”, Vol. 40, pp. 3-16. Abstract Coal plays a vital role in the socio-economic development of China. Yet, the spatial mismatch between production centers (inland Northwest) and consumption centers (coastal region) within China fostered the emergence of dedicated coal transport corridors with limited alternatives. -

51381-001: Shanxi Changzhi Industrial Transformation And

Initial Poverty and Social Analysis October 2018 People’s Republic of China: Shanxi Changzhi Industrial Transformation and Economic Upgrading Demonstration Project This document is being disclosed to the public in accordance with ADB’s Public Communications Policy 2011. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 16 October 2018) Currency unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.14457 $1.00 = CNY6.9170 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CCG – Changzhi City Government GDP – gross domestic product PRC – People’s Republic of China SPG – Shanxi Provincial Government WEIGHTS AND MEASURES km – kilometer km2 – square kilometer NOTE In this report, "$" refers to United States dollars. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. INITIAL POVERTY AND SOCIAL ANALYSIS Country: People’s Republic of China Project Title: Shanxi Changzhi Industrial Transformation and Economic Upgrading Lending/Financing Project Department/ East Asia Department/Urban and Social Modality: Division: Sectors Division I. POVERTY IMPACT AND SOCIAL DIMENSIONS A. Links to the National Poverty Reduction Strategy and Country Partnership Strategy The project is directly linked to the poverty reduction strategy and new-type urbanization of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) through industrial transformation and economic upgrading. It will be implemented in Changzhi City1 in the Southeast of Shanxi Province. The City has a land area of 13,955 km² with 13 counties (cities and districts), 1 national-level high-tech development zone and 4 provincial-level economic and technological development zones. -

The People's Liberation Army's 37 Academic Institutions the People's

The People’s Liberation Army’s 37 Academic Institutions Kenneth Allen • Mingzhi Chen Printed in the United States of America by the China Aerospace Studies Institute ISBN: 9798635621417 To request additional copies, please direct inquiries to Director, China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 55 Lemay Plaza, Montgomery, AL 36112 Design by Heisey-Grove Design All photos licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, or under the Fair Use Doctrine under Section 107 of the Copyright Act for nonprofit educational and noncommercial use. All other graphics created by or for China Aerospace Studies Institute E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/CASI Twitter: https://twitter.com/CASI_Research | @CASI_Research Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CASI.Research.Org LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/11049011 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, Intellectual Property, Patents, Patent Related Matters, Trademarks and Copyrights; this work is the property of the U.S. Government. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights Reproduction and printing is subject to the Copyright Act of 1976 and applicable treaties of the United States. This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This publication is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal, academic, or governmental use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete however, it is requested that reproductions credit the author and China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI).