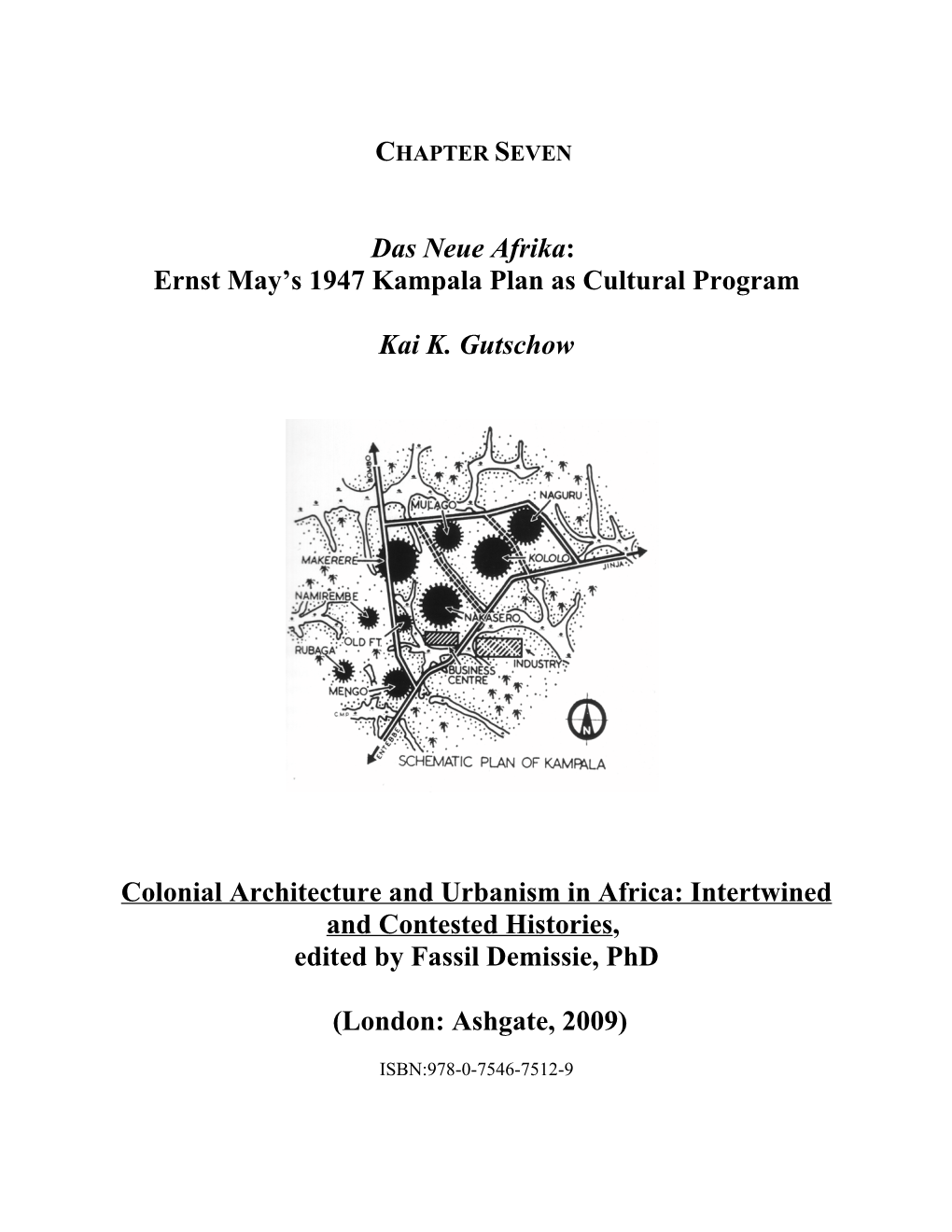

Das Neue Afrika: Ernst May's 1947 Kampala Plan As Cultural Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kafue-Lions Den (Beira Corridor)

Zambia Investment Forum (2011) Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS FRAMEWORK IN ZAMBIA: PRESENTED BY: Mr. Hibene Mwiinga, Deputy Director of National Policy and Programme Implementation MINISTER OF FINANCE AND NATIONAL PLANNING MOFNP OUTLINE: PPP Policy and Legal Framework What is PPP Agenda in Zambia Objectives of PPPs in Zambia Background of PPP in Zambia Pipeline of PPP Projects Key elements of a PPP project Unsolicited Bids Challenges Investment Opportunities in Communications and Transport Sectors MOFNP Policy and Legal Framework PPP Policy approved in 2007 PPP Act enacted in August 2009 MOFNP What is the PPP Agenda in Zambia? To enhance Economic Development in the Country through partnerships between Govt and Private sector; To support the National Vision of the Country which is to make “Zambia to a Prosperous and Middle-Income Country by 2030”; PPPs present a Paradigm shift in way of doing business in Zambia; MOFNP Rationale of taking the PPP route in Zambia Facilitation of Government Service Delivery Public Debt Reduction Promotion of Public Sector Savings Project Cost Savings Value for Money Efficiency in Public Sector Delivery Attraction of Private Sector in Public Goods & Services Investment MOFNP Background of PPPs in Zambia • PPPs are a „recent‟ phenomena in Zambia • Old and classic examples – Zambia Railways Line (Cape-Cairo dream by Cecil Rhodes) – TAZAMA • More recent examples – Railway Systems of Zambia (RSZ) Concession – Urban Markets (BOT) – Maintenance of the Government Complex (Maintenance -

What the Government Is Doing

ishe«l when he puts h "sub" in the chair ownership and management- The tele* THE EVENING STAR, and takes a place among the wrestlers. phono and the telegraph arc unmistaka¬ com¬ FIFTY HEARS AGO The first reason is that he understands bly rival nteans of long-distance WHAT IS DOING GERMANY'S AFRICAN RAILWAY. effective THE become GOVERNMENT congressional subjects and procedure, and munication. They can gives a good account of hijnself. Even supplements, but in the main their func¬ in tions are of a character and 11 THE STAR WASHINGTON, his opponents enjoy seeing him action. competing their con¬ He puts them to their best; and the bebt no public interest is served by Babies have a better chance of living MacVeagh's statement that the matter Few persons, few indeed. ex-Salaam on of 4,000,0ft) mark* was a closed but this has not diplomats, payment SUNDAY December 21, 1913 Is business. solidation. Telephone rates and tele¬ and of growing up into healthy children Incident, ligve followed the silent railway advance to the Sultan of Zanzibar. checked the regular appearance of the Tho in lVfOt* vu The second reason is that Mr. Clark graph rates have remained practicall> tn the Island of New letter of every few days. As the civil war progressed reports were across Africa, and population whereas it complaint ranks of the at 34.600. Including 300 fturopeatt*. Tt>*> is easily the most effective orator on his unchanged since the merger, Illfailt Health in Zealand that In any The last letter was received during the Indicative of discord in the henco they sharo in entrance to harbor lis shielded from THEODOBE W. -

UGANDA BUSINESS IMPACT SURVE¥ 2020 Impact of COVID-19 on Formal Sector Small and Mediu Enterprises

m_,," mm CIDlll Unlocking Public and Private Finance for the Poor UGANDA BUSINESS IMPACT SURVE¥ 2020 Impact of COVID-19 on formal sector small and mediu enterprises l anda Revenue Authority •EUROPEAN UNION UGANDA BUSINESS IMPACT SURVEY 2020 Contents ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................................. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................................. iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. v BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Business in the time of COVID-19 ............................................................................................................ 1 Uganda formal SME sector ........................................................................................................................ 3 SURVEY INFORMATION ................................................................................................................................ 5 Companies by sector of economic activity ........................................................................................... 5 Companies by size ..................................................................................................................................... -

LETSHEGO-Annual-Report-2016.Pdf

INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2016 AbOUT This REPORT Letshego Holdings Limited’s Directors are pleased to present the Integrated Annual Report for 2016. This describes our strategic intent to be Africa’s leading inclusive finance group, as well as our commitment to sustainable value creation for all our stakeholders. Our Integrated Annual Report aims and challenges that are likely to impact to provide a balanced, concise, and delivery of our strategic intent and transparent commentary on our strategy, ability to create value in the short, performance, operations, governance, and medium and long-term. reporting progress. It has been developed in accordance with Botswana Stock The material issues presented in Exchange (BSE) Listing Requirements as the report were identified through well as King III, GRI, and IIRC reporting a stakeholder review process. guidelines. This included formal and informal interviews with investors, sector The cenTral The requirements of the King IV guidelines analysts, Executive and Non- are being assessed and we will address Executive Letshego team members, Theme of The our implementation of these in our 2017 as well as selected Letshego reporT is Integrated Annual Report. customers. sUstaiNAbLE While directed primarily at shareholders A note on diScloSureS vALUE creatiON and providers of capital, this report We are prepared to state what we do and we offer should prove of interest to all our other not disclose, namely granular data on stakeholders, including our Letshego yields and margins as well as on staff an inTegraTed team, customers, strategic partners, remuneration as we deem this to be accounT of our Governments and Regulators, as well as competitively sensitive information the communities in which we operate. -

AN ETHNOGRAPHY of DEAF PEOPLE in TANZANIA By

THEY HAVE TO SEE US: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF DEAF PEOPLE IN TANZANIA by Jessica C. Lee B.A., University of Northern Colorado, 2001 M.A., Gallaudet University, 2004 M.A., University of Colorado, 2006 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the degree requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology 2012 ii This thesis entitled: They Have To See Us: an Ethnography of Deaf People in Tanzania written by Jessica Chantelle Lee has been approved for the Department of Anthropology J. Terrence McCabe Dennis McGilvray Paul Shankman --------------------------------------------- Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # 13090619 iii ABSTRACT They Have To See Us: an Ethnography of Deaf People in Tanzania Jessica Lee Department of Anthropology Thesis directed by Professor J. Terrence McCabe This dissertation explores the relationship between Tanzanian deaf people and mainstream society, as well as dynamics within deaf communities. I argue that deaf people who do participate in NGOs and other organizations that provide support to deaf people, do so strategically. In order to access services and improve their own lives and the lives of their families, deaf people in Tanzania move comfortably and fluidly between identity groups that are labeled as disabled or only as deaf. Through intentional use of the interventions provided by various organizations, deaf people are able to carve out deaf spaces that act as places for transmission of information, safe areas to learn and use sign language, and sites of network and community development among other deaf people. -

Shifts in Modernist Architects' Design Thinking

arts Article Function and Form: Shifts in Modernist Architects’ Design Thinking Atli Magnus Seelow Department of Architecture, Chalmers University of Technology, Sven Hultins Gata 6, 41296 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected]; Tel.: +46-72-968-88-85 Academic Editor: Marco Sosa Received: 22 August 2016; Accepted: 3 November 2016; Published: 9 January 2017 Abstract: Since the so-called “type-debate” at the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne—on individual versus standardized types—the discussion about turning Function into Form has been an important topic in Architectural Theory. The aim of this article is to trace the historic shifts in the relationship between Function and Form: First, how Functional Thinking was turned into an Art Form; this orginates in the Werkbund concept of artistic refinement of industrial production. Second, how Functional Analysis was applied to design and production processes, focused on certain aspects, such as economic management or floor plan design. Third, how Architectural Function was used as a social or political argument; this is of particular interest during the interwar years. A comparison of theses different aspects of the relationship between Function and Form reveals that it has undergone fundamental shifts—from Art to Science and Politics—that are tied to historic developments. It is interesting to note that this happens in a short period of time in the first half of the 20th Century. Looking at these historic shifts not only sheds new light on the creative process in Modern Architecture, this may also serve as a stepstone towards a new rethinking of Function and Form. Keywords: Modern Architecture; functionalism; form; art; science; politics 1. -

Transfers of Modernism: Constructing Soviet Postwar Urbanity

Transfers of Modernism: Constructing Soviet Postwar Urbanity The housing shortage during the postwar period has brought a new surge in the development of prefabrication technologies, especially in 1950s East Germany, France and the Soviet Union— the countries that suffered significant physical damage from the war. Although the prefabrication building techniques were evidently not an invention of the MASHA PANTELEYEVA 1950s and there has been a long tradition of similar types of construction and experi- Princeton University mentation in building culture, the need for a new and improved efficiency in construction rapidly emerged in the situation of an extreme postwar housing crisis. Formed by the multiple geopolitical and economic aspects of the postwar architectural context, the new method focused on the construction with large concrete panels prefabricated offsite, which allowed cutting down production costs and significantly reducing time of construc- tion. This development was inseparable from architecture’s political and social context: most of the building associated with the new typology in the reconstruction period was subsidized by the state, characterized by the intense involvement of political figures. Originally developed in France with the initiative of the Ministry of Reconstruction and Urbanism in the late 1940s, the large-panel system building experienced a rapid adapta- tion across Europe: its aesthetic and technological qualities underwent “back-and-forth” cultural alterations between the countries, and eventually determined the failure of the system in the West, and its long-lasting success in Eastern Europe. The technological basis of most European prefabricated buildings was developed in European states with stable social-democratic policies, particularly in Scandinavia, Great Britain, and France. -

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE. -

Second Kampala Institutional & Infrastructure Development Project

Second Kampala Institutional & Infrastructure Development Project By: JOSEPHINE NALUBWAMA MUKASA Uganda; Kampala City MAP OF AFRICA: LOCATION OF UGANDA UGANDA KAMPALA CITY • Located in Kampala district -North of Lake Victoria • Comprised of five Divisions, Kampala Central Division, Kawempe, Makindye, Nakawa, and Lubaga Division. • Size: 189Km2 • Population: 1. 5million (night) Over 3 million (Day) CITY ADMINISTRATION STRUCTURE KAMPALA INFRASTRUCTURE AND INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Improving mobility, FLOODING IN THE CITY CONGESTION ON THE ROADS connectivity in the city POOR DRAINAGE SYSTEM NON MOTORABLE ROADS OVERVIEW OF THE PROJECT • Goal: To enhance infrastructure and Institutional capacity of the city and improve urban mobility for inclusive economic growth. • Project Duration: 5 years (FY2014 – FY 2019) • Project Financing: The project is financed through an Investment Project Financing (IPF) facility of US$175 million (equivalent) IDA Credit and GoU/KCCA counterpart funding of US$8.75 million equivalents. The total project financing is US$183.75 million • Stake holders: Communities, World Bank, Government of Uganda, Utility companies KEY ISSUES OF PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION • Delays in securing right of way due to contestation of the approved values, mortgaged titles, Titles with Caveats, absent land lords among others; • Delay in securing land for resettlement of project affected persons; • Uncooperative property owners in providing pertinent information; • Sometimes poor political atmosphere – the different political campaigns -

Die Späten Ernst-May-Siedlungen in Hessen

Die späten Ernst-May-Siedlungen in Hessen Maren Harnack Paola Wechs Julian Glunde Die späten Ernst-May-Siedlungen in Hessen Schelmengraben Klarenthal Parkfeld Kranichstein Die späten Ernst-May-Siedlungen in Hessen Eine Untersuchung von Prof. Dr.-Ing. Maren Harnack, MA Paola Wechs und Julian Glunde In Zusammenarbeit mit dem .andesamt fØr DenkmalRƃege Hessen Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences Fachbereich 1 Architektur, Bauingenieurwesen, Geomatik Nibelungenplatz 1 60318 Frankfurt am Main [email protected] Gestaltung Elmar Lixenfeld / www.duodez.de ISBN 978-3-947273-20-1 © 2019 Maren Harnack Inhalt 7 Einleitung 9 Kriterien für die Beschreibung und Bewertung von Siedlungen der Nachkriegsmoderne Planerisches Konzept / Geschichtliche Bedeutung / Städtebauliche Struktur / Architektur / Freiraumstruktur / Freiraumgestaltung / Erschließungsstruktur / Einbindung in die Umgebung 19 Fallstudien 20 Schelmengraben Wiesbaden Beschreibung Bewertung 66 Klarenthal Wiesbaden Beschreibung Bewertung 110 Parkfeld Wiesbaden Beschreibung Bewertung 148 Kranichstein Darmstadt Beschreibung Bewertung 190 Prinzipien für die Weiterentwicklung von Siedlungen der Nachkriegsmoderne Allgemeingültige Prinzipen Wiesbaden / Schelmengraben / Klarenthal / Parkfeld / Darmstadt Kranichstein 233 Wie weiterbauen? 235 Quellen Literatur / Bildnachweis Einleitung 7 Deutschlandweit herrscht in den prosperierenden Ballungsräumen ein Mangel an günstigem Wohnraum. Viele Großstädte verfügen kaum noch über Baulandreserven, und neu auszuweisendes Bauland konkurriert mit -

Transport Sector Support Project

PROJECT INFORMATION DOCUMENT (PID) APPRAISAL STAGE Report No.: AB4792 TRANSPORT SECTOR SUPPORT PROJECT Project Name Public Disclosure Authorized Region AFRICA Sector Roads and highways (62%); Aviation (24%); Agricultural markets and trade (10%); General transportation sector (4%) Themes: Rural services and infrastructure (72%); Infrastructure services for private sector development (26%); Other public sector governance (2%) Project ID P055120 Borrower(s) GOVERNMENT OF TANZANIA United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs P.O. Box 9111 Tanzania Public Disclosure Authorized Tel: +255 22 2112854 Fax: +255 22 2117090 / 2110326 Implementing Agencies Tanzania National Roads Agency (TANROADS) Tanzania Airports Authority (TAA) Ministry of Infrastructure Development (MoID) Environment Category [] A [X] B [ ] C [ ] FI [] TBD (to be determined) Date PID Prepared March 18, 2010 Date of Appraisal March 1, 2010 Authorization Date of Board Approval May 27, 2010 I. Country and sector issues Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Tanzania’s Economy. From 2002 to 2008 Tanzania has experienced sustained growth of around seven percent thanks to the implementation, since the mid nineties, of a comprehensive economic reform program that has produced good macroeconomic performance and stability characterized by relatively high economic growth and low inflation. The global financial crisis has resulted in a decline in growth from 7.4 percent in 2008 to five percent in 2009. One of the country’s main challenges remains to translate economic growth into poverty reduction, with the country registering only a small decline in poverty incidence from 35.7 percent in 2000 to 33.5 percent in 2007. Key growth sectors are mining, construction, manufacturing, and tourism—all sectors that strongly depend on and generate transport. -

Owned Spaces and Shared Places

UGANDA Owned Spaces and Shared Places: Refugee Access to Livelihoods and Housing, Land, and Property in Uganda September 2019 Cover photo: Kyaka II refugee settlement. © IMPACT/2019 About REACH REACH Initiative facilitates the development of information tools and products that enhance the capacity of aid actors to make evidence-based decisions in emergency, recovery and development contexts. The methodologies used by REACH include primary data collection and in-depth analysis, and all activities are conducted through inter-agency aid coordination mechanisms. REACH is a joint initiative of IMPACT Initiatives, ACTED and the United Nations Institute for Training and Research - Operational Satellite Applications Programme (UNITAR-UNOSAT). For more information please visit our website: www.reach-initiative.org. You can contact us directly at: [email protected] and follow us on Twitter @REACH_info. About Norwegian Refugee Council The Norwegian Refugee Council is an independent humanitarian organisation working to protect the rights of displaced and vulnerable people during crises. NRC provides assistance to meet immediate humanitarian needs, prevent further displacement and contribute to durable solutions. NRC is Norway’s largest international humanitarian organisation and widely recognised as a leading field-based displacement agency within the international humanitarian community. NRC is a rights-based organisation and is committed to the humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, independence and impartiality. Refugee Access to Livelihoods and Housing, Land, and Property in Uganda – September 2019 AWKNOWLEDGEMENTS REACH Initiative and NRC would like to thank the government of Uganda’s Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) and the United Nations Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) for their assistance in designing and guiding this assessment.