Fragmentation and Narcissism in Lucian Freud and Jenny Saville

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diminishing Connections Mary Jane King Clemson University, M.J [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2016 Diminishing Connections Mary Jane King Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation King, Mary Jane, "Diminishing Connections" (2016). All Theses. 2369. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2369 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIMINISHING CONNECTIONS ___________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School Of Clemson University ___________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Visual Art ___________________________________________________ by Mary Jane King May 2016 ___________________________________________________ Accepted by: Professor Todd McDonald, Committee Chair Professor Kathleen Thum Professor Todd Anderson Dr. Andrea Feeser ABSTRACT I explore our skin’s durability as it protects our inner being, but its fragility in our death. Paint allows me to understand the physical quality of skin and the structure underneath it’s surface. We experience the world and one another through this outermost layer of our selves, providing the ability to feel touch and to establish corporeal bounds and connections. Skin provides a means of communication and interaction, of touch and intimacy. It contains, protects, and stretches with the growth of the body, adapting to the interior bodily demands. It is through this growth that there is also a regression or a slow decay of the body. In addition to exterior exploration, I also investigate the vitality of our viscera even when disease destroys it and claims our lives. -

Sacred Psychoanalysis” – an Interpretation Of

“SACRED PSYCHOANALYSIS” – AN INTERPRETATION OF THE EMERGENCE AND ENGAGEMENT OF RELIGION AND SPIRITUALITY IN CONTEMPORARY PSYCHOANALYSIS by JAMES ALISTAIR ROSS A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham July 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT From the 1970s the emergence of religion and spirituality in psychoanalysis is a unique development, given its traditional pathologizing stance. This research examines how and why ‘sacred psychoanalysis’ came about and whether this represents a new analytic movement with definable features or a diffuse phenomena within psychoanalysis that parallels developments elsewhere. After identifying the research context, a discussion of definitions and qualitative reflexive methodology follows. An account of religious and spiritual engagement in psychoanalysis in the UK and the USA provides a narrative of key people and texts, with a focus on the theoretical foundations established by Winnicott and Bion. This leads to a detailed examination of the literary narratives of religious and spiritual engagement understood from: Christian; Natural; Maternal; Jewish; Buddhist; Hindu; Muslim; Mystical; and Intersubjective perspectives, synthesized into an interpretative framework of sacred psychoanalysis. -

PRESS RELEASE Face Time: an Exhibition in Aid of the Art Room

PRESS RELEASE Face Time: An exhibition in aid of The Art Room Threadneedle Space, Mall Galleries, London SW1 Monday 16 – Saturday 21 June 2014 10 am – 5 pm, Free Admission Over 60 works of art by international leading artists will be offered for sale in aid of The Art Room in Face Time, a week-long exhibition at the Threadneedle Space, Mall Galleries, London, SW1. Working in partnership with the Threadneedle Foundation, The Art Room, a national charity offering art as a therapeutic intervention to children and young people, have invited artists to contribute a clock or original piece of work for this important fundraising exhibition. Painters, sculptors, illustrators, architects and photographers have all contributed to Face Time and many have chosen to produce a clock face which reflects a key element of The Art Room’s methodology and practice. Face Time artists include: Emma Alcock ▪ Nicola Bayley ▪ Paul Benney ▪ Alison Berrett ▪ Tess Blenkinsop ▪ Anthony Browne ▪ Sarah Campbell ▪ Jake & Dinos Chapman ▪ Lauren Child ▪ Robert James Clarke ▪ Lara Cramsie ▪ Martin Creed ▪ Miranda Creswell ▪ Emma Faull ▪ Eleanor Fein ▪ Jennie Foley ▪ Antony Gormley ▪ Nicola Gresswell ▪ David Anthony Hall ▪ Maggi Hambling ▪ Kevin Harman ▪ The Art Room (Oxford) Oxford Spires Academy, Glanville Road, Oxford OX4 2AU (Registered Address) T 01865 779779 E [email protected] W www.theartroom.org.uk Founder Director Juli Beattie Chair Jonathan Lloyd Jones Patrons Micaela Boas, Anthony Browne, His Honour Judge Nicholas Browne QC, Dr Mina Fazel, MRCPsych -

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

Good Practice

GOOD PRACTICE Negotiating your practice £5.00 GOOD PRACTICE NEGOTIATING YOUR PRACTICE Edited Gillian Nicol CONTENTS Publisher Louise Wirz Design www.axisgraphicdesign.co.uk Introduction 3 © writers, artists and a-n The Artists Information Company 2006 The Bata-ville project 4 ISBN 0 907730 72 8 Published by Public art and compromise 6 a-n The Artists Information Company Registered in England Company No 1626331 Expectations and responsibilities 8 Registered address First Floor, 7-15 Pink Lane, Newcastle upon Tyne The artist-curator dynamic 9 NE1 5DW UK +44 (0) 191 241 8000 [email protected] Public commission 10 www.a-n.co.uk Copyright Critical context for practice 12 Individuals may copy this publication for the limited purpose of use in their business or professional Social spaces 13 practice. Organisations wishing to copy or use the publication for multiple purposes should contact the Publisher for permission. Negotiating a better rate of pay 14 a-n The Artists Information Company’s publications and programmes are enabled by artists who form Join a-n 15 our largest stakeholder group, contributing some £340K annually in subscription income, augmented by revenue funds from Arts Council England, and Publications 16 support for specific projects from Esmée Fairbairn Foundation. Anne Brodie, untitled, glass and white china clay, 2003. ‘Artists and Writers’ in Antarctica is a scheme that is jointly run by Arts Council England and the British Antarctic Survey. Anne Brodie will be one of two resident artists in Antarctica as part of this scheme from December 2006 – February 2007. “My work usually involves lots of hot glass, film and photography. -

Archives Fine Books Catalogue 12

ARCHIVES FINE BOOKS CATALOGUE 12 2020 rom early March 2020, Catalogue 12 was never a certainty. We held our breath and watched as events were cancelled and postponed, including the ANZAAB Antiquarian and Rare Book Fairs. But in the slowing and stilling of those weeks and months something lovely happened: Archives FFine People called and ordered books or bought them through our website, and many booked appointments for quiet, socially distant browsing. Dedicated book collectors kept collecting books and others discovered they loved books too. We didn’t acquire much stock in this period, but when we were offered a small collection of mid-to-late twentieth century illustrated and signed items we were feeling cheery and hopeful, took them on, and Catalogue 12 came into being. Between the covers you will find John and Yoko, Ray Bradbury, Three Dog Night, Harvey Kurtzman, Jenny Saville and more. True to form we have tucked a little William Blake in the mix on pp. 6 & 17. We hope you enjoy browsing and if we can reserve something special for you please let us know. Dawn & Hamish. Front Cover: Ono, Yoko. Grapefruit. New York: ARCHIVES FINE BOOKS PTY LTD Sphere, 1971. First Thus. SIGNED BY YOKO ONO AND JOHN LENNON. (# 1263). Details p. 4. 40 CHARLOTTE STREET, BRISBANE, QUEENSLAND, 4000 ‡ +61 7 3221 0491 Back Cover: Detail from SAVILLE, Jenny. Jenny Saville. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, [email protected] Inc., 2005. First Edition. SIGNED. Details p. 15. www.archivesfinebooks.com.au 2 The John Lennon Letters; Edited and with an Introduction by Hunter Davies. -

Self-Portrait) My Work Is Purely Autobiographical

ART AND IMAGES IN PSYCHIATRY SECTION EDITOR: JAMES C. HARRIS, MD Lucian Freud’s Reflection (Self-Portrait) My work is purely autobiographical. It is about myself and my surroundings. It is an attempt at a record. I work with people that interest me, and that I care about and think about, in rooms that I live in and know. Lucian Freud1(p7) UCIAN FREUD (1922-2011), byKennethClark.5 Thedistinctionbetween phasized thickly applied white and deep grandson of Sigmund Freud, naked and nude is central to Clark’s dis- red colors. is considered to be the leading cussion. Clark writes that “to be naked is Because Freud stood when he painted, realist painter of the last cen- to be deprived of our clothes, and the word his figures often appear foreshortened. He Ltury. His father Ernst Freud, an architect, implies some of the embarrassment most preferred not to use professional models was the 4th of Sigmund Freud’s 6 children of us feel in that condition,”5(p23) but that as his subjects. Instead, his models were and was the youngest son. Lucian grew up the nude is balanced and confident. “[I]n peoplefromallwalksoflifewhomheknew, in Berlin, Germany, far from the influ- the greatest age of painting, the nude in- including his adult daughters, who found ence of the birthplace of psychoanalysis spired the greatest works.”5(p23) For Clark, thatposingforhimwasoneoftheonlyways in Vienna, Austria. Grandfather Sigmund the nude as a conceptual and artistic cat- to spend time with him and to get to know visited Lucian’s family in Berlin regularly egoryalwaysinvolvedthenotionofanideal him as a father. -

Futuristic Aerie with a Park View

C M Y K Nxxx,2012-05-11,C,023,Bs-4C,E1 N C23 FRIDAY, MAY 11, 2012 Futuristic Aerie With a Park View RICHARD PERRY/THE NEW YORK TIMES By CAROL VOGEL For the past 15 summers the Met’s “Tomás Saraceno on the Roof: about a dozen installers assembling his most spinning around from the perspec- roof garden has been the setting for tra- creation, which he described as “an in- N Tomás Saraceno’s imagination his Cloud City” opens Tuesday at the tive inside this giant futuristic construc- ditional sculptures by artists like Ells- ternational space station.” As pieces be- constellation of 16 joined modules Metropolitan Museum of Art. tion. worth Kelly, Jeff Koons and, last year, gan to be set in place, Mr. Saraceno under construction on the roof of Like many of Mr. Saraceno’s installa- Anthony Caro. It has also been a place sneaked a visitor inside and up a twisty tions “Cloud City” is his vision of float- I the Metropolitan Museum of Art to walk up a winding bamboo pathway gonal habitat of reflective stainless steel staircase about 20 feet above the roof ing or flying cities — places that defy will take off in a heavy puff of wind and that soared some 50 feet in an untradi- and acrylic. garden. Some of the floors were trans- float over Central Park. “The whole conventional notions of space, time and tional installation that invited visitor Called “Cloud City,” it is the largest of parent, and the walls were mirrored gravity. “You can have a feeling of thing will go into orbit,” Mr. -

Gagosian Gallery

The Brooklyn Rail June 5, 2018 GAGOSIAN Jenny Saville: Ancestors Jason Rosenfeld Jenny Saville, Byzantium, 2018. © Jenny Saville. Photo: by Mike Bruce. Courtesy Gagosian. The athleticism of Jenny Saville’s brushwork and draughtsmanship has been the hallmark of her work since her earliest exhibition in New York, at Gagosian's Wooster Street incarnation in 1999. She was then associated with Damien Hirst's band of Young British Artists, riding the Cool Britannia wave and establishing London as a prime destination for contemporary art for the first time since Victoria was queen. The elegance of Saville’s facture, the swirling and energetic pace of her drawing, made her inheritor of a tradition of gestural, bravura painting going back to Titian, Rubens, and Velázquez, and as reworked by John Everett Millais and Édouard Manet, and finally perfected by John Singer Sargent in the late-nineteenth century. This was then reprised and critiqued in the abstracted figuration of de Kooning and the visceral reconstitution of form of Lucien Freud in the post-war era. All those gesticulative men. If you were open to being energized by the pleasure of agilely pushed paint in the service of a kind of post-academic, post-modern, post-minimal realism, then Saville delivered, and her edgy subject matter paralleled a wave of artistic interest in the body, the self, the gaze, and the abject. By a woman. On a huge scale. In her second New York show, Migrants, the sight of Suspension (2002 – 03), featuring a headless pig sprawled on its side across almost fifteen feet of canvas and hung just off the ground in Gagsosian’s Chelsea digs at 24th Street in the spring of 2003 was memorable and remarkable. -

IMMA Collection: Freud Project 2016 - 2021 Introduction

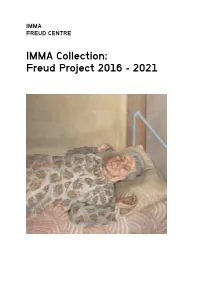

IMMA FREUD CENTRE IMMA Collection: Freud Project 2016 - 2021 Introduction Since 2016 IMMA has presented the IMMA Collection: Freud Project, a five year loan to the Collection of 52 works by Lucian Freud (1922-2011), one of the greatest realist painters of the 20th century. 2021 is the final year of the Freud Project at IMMA and as we emerge from the global effect of Covid-19 we are delighted to bring to our audiences as our concluding programme or ‘finissage’, a combination of digital and physical elements, the exhibition The Artist’s Mother: Lucie and Daryll – a response by Chantal Joffe; The Maternal Gaze, a series of short videos by 22 artists and creatives in response to the theme of the Artist’s Mother and Soul Outsider, a new contemporary music commission composed by Deirdre Gribbin and performed by Crash Ensemble, in a recording that accompanies Freud’s portraits in the Freud Centre. www.imma.ie/whats-on/imma-collection-freud-project-the-artists-mother Front cover Lucian Freud, The Painter’s Mother Resting I, 1976, Oil on canvas, 90.2 x 90.2 cm, Collection Irish Museum of Modern Art, On Loan, Private Collection © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images 2 Chantal Joffe My Mother with Fern, 2017, Oil on canvas, 40.8 x 31.3 cm © The artist 3 The Artist’s Mother: Lucie and Daryll - a response by Chantal Joffe Room One We invited artist Chantal Joffe to begin a dialogue with Lucian Freud’s portraits of his mother as part of our ongoing programme in the context of the Freud Project. -

WRAP Theses Davis 2016.Pdf

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/80978 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Performing Migratory Identity – Practice-as-Research on Displacement and (Be)Longing by Natasha Davis Thesis Submitted to The University of Warwick in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Theatre, Performance and Cultural Policy Studies Faculty of Arts May 2016 Contents List of figures 4 Acknowledgments 6 Declaration 8 Abstract 9 Arrival 10 Departing, arriving, repeating and returning 11 Between knowing and unknowing 19 Before the Encounters 22 Before the performance there was a story that really happened 23 Border crossings: before and after the split and dislocation 24 A citizen of no country 30 Decay of the body, decay of the land 36 Encounter One 42 No-body, in exile 43 Rupture 45 Small things can throb in our insides for a long time 50 Asphyxia 59 Like a rabid dog, sensitive to every sound 65 Suspended 69 2 In the place where I was born nobody is waiting for me 75 After the trilogy 82 Encounter Two 84 About practice-as-research methodology 85 Cartographies of memory 96 Section one: -

Lucian Freud Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LUCIAN FREUD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Feaver | 488 pages | 06 Nov 2007 | Rizzoli International Publications | 9780847829521 | English | New York, United States Lucian Freud PDF Book Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, pp. They are generally sombre and thickly impastoed, often set in unsettling interiors and urban landscapes. Hotel Bedroom Settling in Paris in , Freud painted many portraits, including Hotel Bedroom , which features a woman lying in a bed with white sheets pulled up to her shoulders. Freud moved to Britain in with his parents after Hitler came to power in Germany. Lucian Freud, renowned for his unflinching observations of anatomy and psychology, made even the beautiful people including Kate Moss look ugly. Michael Andrews — Freud belonged to the School of London , a group of artists dedicated to figurative painting. Retrieved 9 February The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 January Freud was one of a number of figurative artists who were later characterised by artist R. The works are noted for their psychological penetration and often discomforting examination of the relationship between artist and model. Wikipedia article. His series of paintings and drawings of his mother, begun in and continuing until the day after her death in , are particularly frank and dramatic studies of intimate life passages. Freud worked from life studies, and was known for asking for extended and punishing sittings from his models. The work's generic title, giving no hint of the specifics of the sitter or the setting, reflects the consistent, clinical detachment with which Freud approached all subjects, no matter what their relationship to him. Ria, Naked Portrait , a nude completed in , required sixteen months of work, with the model, Ria Kirby, posing all but four evenings during that time.