Trachemys Scripta Elegans (Red-Eared Slider) Management Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.MORPHOLOGY and CONSERVATION of the MESOAMERICAN SLIDER (Trachemys Venusta, Emydidae) from the ATRATO RIVER BASIN, COLOMB

Acta Biológica Colombiana ISSN: 0120-548X [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Sede Bogotá Colombia CEBALLOS, CLAUDIA P.; BRAND, WILLIAM A. MORPHOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF THE MESOAMERICAN SLIDER (Trachemys venusta, Emydidae) FROM THE ATRATO RIVER BASIN, COLOMBIA Acta Biológica Colombiana, vol. 19, núm. 3, septiembre-diciembre, 2014, pp. 483-488 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Sede Bogotá Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=319031647014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative SEDE BOGOTÁ ACTA BIOLÓGICA COLOMBIANA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DEPARTAMENTO DE BIOLOGÍA ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN MORPHOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF THE MESOAMERICAN SLIDER (Trachemys venusta, EMYDIDAE) FROM THE ATRATO RIVER BASIN, COLOMBIA Morfología y conservación de la tortuga hicotea Mesoamericana (Trachemys venusta, Emydidae) del río Atrato, Colombia CLAUDIA P. CEBALLOS1, Ph. D.; WILLIAM A. BRAND2, Ecol. 1 Grupo Centauro. Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias, Universidad de Antioquia. Carrera 75 n.º 65-87, of. 47- 122, Medellín, Colombia. [email protected] 2 Corpouraba. Calle 92 n.º 98-39, Turbo, Antioquia, Colombia. [email protected] Author for correspondence: Claudia P. Ceballos, [email protected] Received 20th February 2014, first decision 14th May 2014, accepted 05th June 2014. Citation / Citar este artículo como: CEBALLOS CP, BRAND WA. Morphology and conservation of the mesoamerican slider (Trachemys venusta, Emydidae) from the Atrato River basin, Colombia. Acta biol. Colomb. 2014;19(3):483-488 ABSTRACT The phylogenetic relationships of the Mesoamerican Slider, Trachemys venusta, that inhabits the Atrato River basin of Colombia have been controversial as three different names have been proposed during the last 12 years: T. -

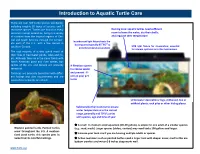

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

Movement and Habitat Use of Two Aquatic Turtles (Graptemys Geographica and Trachemys Scripta) in an Urban Landscape

Urban Ecosyst DOI 10.1007/s11252-008-0049-8 Movement and habitat use of two aquatic turtles (Graptemys geographica and Trachemys scripta) in an urban landscape Travis J. Ryan & Christopher A. Conner & Brooke A. Douthitt & Sean C. Sterrett & Carmen M. Salsbury # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2008 Abstract Our study focuses on the spatial ecology and seasonal habitat use of two aquatic turtles in order to understand the manner in which upland habitat use by humans shapes the aquatic activity, movement, and habitat selection of these species in an urban setting. We used radiotelemetry to follow 15 female Graptemys geographica (common map turtle) and each of ten male and female Trachemys scripta (red-eared slider) living in a man-made canal within a highly urbanized region of Indianapolis, IN, USA. During the active season (between May and September) of 2002, we located 33 of the 35 individuals a total of 934 times and determined the total range of activity, mean movement, and daily movement for each individuals. We also analyzed turtle locations relative to the upland habitat types (commercial, residential, river, road, woodlot, and open) surrounding the canal and determined that the turtles spent a disproportionate amount of time in woodland and commercial habitats and avoided the road-associated portions of the canal. We also located 21 of the turtles during hibernation (February 2003), and determined that an even greater proportion of individuals hibernated in woodland-bordered portions of the canal. Our results clearly indicate that turtle habitat selection is influenced by human activities; sound conservation and management of turtle populations in urban habitats will require the incorporation of spatial ecology and habitat use data. -

( Malaclemys Terrapin Littoralis) at South Deer Island in Galveston Bay

DistrictCover.fm Page 1 Thursday, May 20, 2004 2:19 PM In cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Occurrence of the Diamondback Terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin littoralis) at South Deer Island in Galveston Bay, Texas, April 2001–May 2002 Open-File Report 03–022 TEXAS Galveston Bay GULF OF EXICO M U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Drawing of Diamondback terrapin by L.S. Coplin, U.S. Geological Survey. U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Occurrence of the Diamondback Terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin littoralis) at South Deer Island in Galveston Bay, Texas, April 2001–May 2002 By Jennifer L. Hogan U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 03–022 In cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Austin, Texas 2003 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. For additional information write to District Chief U.S. Geological Survey 8027 Exchange Dr. Austin, TX 78754–4733 E-mail: [email protected] Copies of this report can be purchased from U.S. Geological Survey Information Services Box 25286 Denver, CO 80225–0286 E-mail: [email protected] ii CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

EMYDIDAE P Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles

REPTILIA: TESTUDINES: EMYDIDAE P Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Pseudemysj7oridana: Baur, 1893:223 (part). Pseudemys texana: Brimley, 1907:77 (part). Seidel, M.E. and M.J. Dreslik. 1996. Pseudemys concinna. Chrysemysfloridana: Di tmars, 1907:37 (part). Chrysemys texana: Hurter and Strecker, 1909:21 (part). Pseudemys concinna (LeConte) Pseudemys vioscana Brimley, 1928:66. Type-locality, "Lake River Cooter Des Allemands [St. John the Baptist Parrish], La." Holo- type, National Museum of Natural History (USNM) 79632, Testudo concinna Le Conte, 1830: 106. Type-locality, "... rivers dry adult male collected April 1927 by Percy Viosca Jr. of Georgia and Carolina, where the beds are rocky," not (examined by authors). "below Augusta on the Savannah, or Columbia on the Pseudemys elonae Brimley, 1928:67. Type-locality, "... pond Congaree," restricted to "vicinity of Columbia, South Caro- in Guilford County, North Carolina, not far from Elon lina" by Schmidt (1953: 101). Holotype, undesignated, see College, in the Cape Fear drainage ..." Holotype, USNM Comment. 79631, dry adult male collected October 1927 by D.W. Tesrudofloridana Le Conte, 1830: 100 (part). Type-locality, "... Rumbold and F.J. Hall (examined by authors). St. John's river of East Florida ..." Holotype, undesignated, see Comment. Emys (Tesrudo) concinna: Bonaparte, 1831 :355. Terrapene concinna: Bonaparte, 183 1 :370. Emys annulifera Gray, 183 1:32. Qpe-locality, not given, des- ignated as "Columbia [Richland County], South Carolina" by Schmidt (1953: 101). Holotype, undesignated, but Boulenger (1889:84) listed the probable type as a young preserved specimen in the British Museum of Natural His- tory (BMNH) from "North America." Clemmys concinna: Fitzinger, 1835: 124. -

In AR, FL, GA, IA, KY, LA, MO, OH, OK, SC, TN, and TX): Species in Red = Depleted to the Point They May Warrant Federal Endangered Species Act Listing

Southern and Midwestern Turtle Species Affected by Commercial Harvest (in AR, FL, GA, IA, KY, LA, MO, OH, OK, SC, TN, and TX): species in red = depleted to the point they may warrant federal Endangered Species Act listing Common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) – AR, GA, IA, KY, MO, OH, OK, SC, TX Florida common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina osceola) - FL Southern painted turtle (Chrysemys dorsalis) – AR Western painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) – IA, MO, OH, OK Spotted turtle (Clemmys gutatta) - FL, GA, OH Florida chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia chrysea) – FL Western chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia miaria) – AR, FL, GA, KY, MO, OK, TN, TX Barbour’s map turtle (Graptemys barbouri) - FL, GA Cagle’s map turtle (Graptemys caglei) - TX Escambia map turtle (Graptemys ernsti) – FL Common map turtle (Graptemys geographica) – AR, GA, OH, OK Ouachita map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis) – AR, GA, OH, OK, TX Sabine map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis sabinensis) – TX False map turtle (Graptemys pseudogeographica) – MO, OK, TX Mississippi map turtle (Graptemys pseuogeographica kohnii) – AR, TX Alabama map turtle (Graptemys pulchra) – GA Texas map turtle (Graptemys versa) - TX Striped mud turtle (Kinosternon baurii) – FL, GA, SC Yellow mud turtle (Kinosternon flavescens) – OK, TX Common mud turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum) – AR, FL, GA, OK, TX Alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii) – AR, FL, GA, LA, MO, TX Diamond-back terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) – FL, GA, LA, SC, TX River cooter (Pseudemys concinna) – AR, FL, -

Get to Know Your Neighborhood Turtles! We All Love Turtles

Originally published in the October and November 2017 Woodlake Life on the Lake Newsletter Get to know your neighborhood turtles! We all love turtles. Some of us have pet turtles and some of us are big fans of Ninja turtles. But we can do a little bit more to secure the future of these fascinating creatures. This article introduces the turtles in Woodlake and what can we do to protect them. I was driving on the Woodlake Village Parkway with my daughter, when we spotted a box turtle crossing the road. We changed the lane to avoid hitting the turtle, and turned around hoping to help the turtle cross the road. After 10 seconds, we were so sad to find the crushed turtle on the middle of the road. That was a very upsetting moment for both me and my four year old. May be the driver of the big truck did not see it…or may be the driver was too distracted to avoid it. Vehicle collisions are one of the major causes of turtle mortality. But if we were willing to stop or change the lane, we could have saved many of those turtles! Turtles are fascinating creatures for many reasons! Some ancient civilizations considered turtles as sacred animals and they believed that our world is supported by a giant “cosmic turtle”. Turtles are one of the oldest vertebrate groups on the planet earth, roaming around for about 220 million years, since before the time of dinosaurs. At the same time, turtles have a really long lifespan and scientists believe that many of them can easily surpass 100 years. -

Three New Subspecies of Trachemys Venusta (Testudines: Emydidae) from Honduras, Northern Yucatán (Mexico), and Pacific Coastal Panama

Three New Subspecies of Trachemys venusta (Testudines: Emydidae) from Honduras, Northern Yucatán (Mexico), and Pacific Coastal Panama By William P. McCord1, Mehdi Joseph-Ouni2, Cris Hagen3, and Torsten Blanck4 1East Fishkill Animal Hospital, Hopewell Junction, NY, USA; 2EO Wildlife & Wilderness Conservation, Brooklyn NY, USA; 3Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, Aiken, SC, USA; 4Forstgartenstr 44, Deutschlandsberg, Austria Abstract. Upon examination of live and preserved specimens from across the species range, several unnamed distinct forms of Trachemys venusta (Gray, 1855) were recognized, leading to the description here of three biogeographically isolated, morphologically distinct subspecies: Trachemys venusta uhrigi ssp. nov., Trachemys venusta iversoni ssp. nov., and Trachemys venusta panamensis ssp. nov. Head and neck stripes, along with cara- pacial and plastral patterns are critical to identification in this group. Formal descriptions and diagnoses are given herein. Other Central American Trachemys are also discussed for comparison. Keywords: Turtle, emydid, Trachemys venusta uhrigi ssp. nov., Trachemys venusta iversoni ssp. nov., Trachemys venusta panamensis ssp. nov., Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Meso-America. Slider turtles of the genus Trachemys GRAY (1855) declared eight syntypes for his “Venus- Agassiz, 1857, range from north and east of like” Emys without designating a holotype. However, the Rio Grande in the United States, in 1873 he referred to only one syntype as “Emys through Mexico, Central America, the venusta”: stuffed specimen “e” (1845.8.5.26) in the West Indies, and South America as far as British Museum of Natural History, labeled “Charming northeastern Argentina. IVERSON (1985) resurrect- Emys” for its beautiful pattern — this reference led ed Trachemys from synonymy with Pseudemys (Gray, SMITH and SMITH (1979) to designate BMNH 1855). -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Report of Two Subspecies of an Alien Turtle, Trachemys Scripta Scripta and Trachemys Scripta Elegans (Testudines: Emydidae) Shar

Correspondence ISSN 2336-9744 (online) | ISSN 2337-0173 (print) The journal is available on line at www.ecol-mne.com Report of two subspecies of an alien turtle, Trachemys scripta scripta and Trachemys scripta elegans (Testudines: Emydidae) sharing the same habitat on the island of Zakynthos, Greece ALEKSANDAR UROŠEVI Ć University of Belgrade, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stankovi ć”, Bulevar despota Stefana 142, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia, E-mail: [email protected] Received 11 December 2014 │ Accepted 26 December 2014 │ Published online 28 December 2014. Introduction of alien aquatic turtles, especially the invasive red-eared slider, Trachemys scripta elegans (Wied-Neuwied 1839) has been noted as a global problem (Scalera 2006; Bringsøe 2006). In Greece only, introductions of the red-eared slider have already been published for several localities: Athens, Corfu, Crete, Kos and Zakynthos (Bruekers 1993; Bruekers et al . 2006; Zenetos et al . 2009). Until the EU banned the import and trade of the red-eared slider (Council Regulation No. 338/97), tens of millions of these turtles had been imported into Europe (Bringsøe 2006). Since the ban, the yellow-bellied slider Trachemys scripta scripta (Schoepff 1792) emerged in the European pet trade as one of the “substitute” species and subspecies (Adrados et al. 2002; Bringsøe 2006). Although it is sold in smaller quantities, and at a higher price, numbers of this subspecies found in the wild in Europe are increasing (Bringsøe 2006). The spread of T. s. scripta has been documented in Spain (Martínez Silvestre et al . 2006; Alarcos et al . 2010; Valdeón et al . 2010), Sweden, Finland (Bringsøe 2006) and Austria (Kleewein 2014). -

The Spatial Configuration of Greenspace Affects Semi-Aquatic

Landscape and Urban Planning 117 (2013) 46–56 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Landscape and Urban Planning jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landurbplan Research paper The spatial configuration of greenspace affects semi-aquatic turtle occupancy and species richness in a suburban landscape a,∗ b a Jacquelyn C. Guzy , Steven J. Price , Michael E. Dorcas a Department of Biology, Davidson College, Davidson, NC 28035-7118, United States b Department of Forestry, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40546-0073, United States h i g h l i g h t s • We sampled semi-aquatic turtles from 2010 to 2011 at 20 suburban ponds. • We used a hierarchical Bayesian model to estimate species richness and occupancy. • Species richness and occupancy increased with greater connectance of greenspaces. • Richness was greater at golf ponds than rural or urban ponds indicating suitability. • In suburban areas, maintaining connectivity of greenspaces should be a priority. a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Within urbanized areas, the importance of greenspaces for wildlife has been widely investigated for Received 10 April 2012 some animal groups, but reptiles have generally been neglected. To assess the importance of the amount, Received in revised form 17 April 2013 spatial distribution, and configuration of greenspaces (comprised of terrestrial and aquatic areas), we Accepted 24 April 2013 examined semi-aquatic turtle species richness in urbanized areas. In this study, we sampled turtles from 2010 to 2011 at 20 ponds, including farm (rural) ponds, ponds in urbanized environments, and Keywords: golf course ponds.