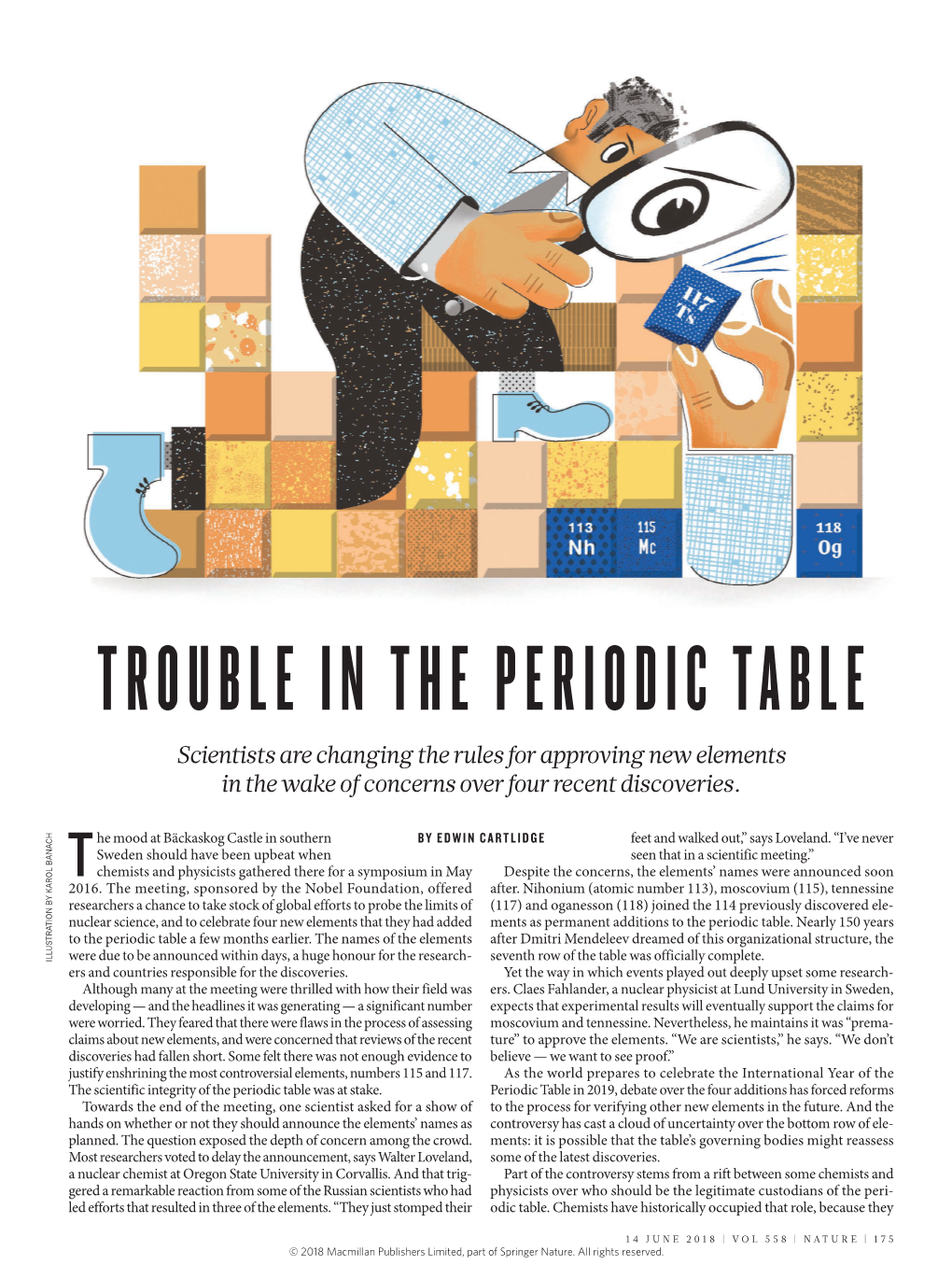

TROUBLE in the PERIODIC TABLE Scientists Are Changing the Rules for Approving New Elements in the Wake of Concerns Over Four Recent Discoveries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Alternate Graphical Representation of Periodic Table of Chemical Elements Mohd Abubakr1, Microsoft India (R&D) Pvt

An Alternate Graphical Representation of Periodic table of Chemical Elements Mohd Abubakr1, Microsoft India (R&D) Pvt. Ltd, Hyderabad, India. [email protected] Abstract Periodic table of chemical elements symbolizes an elegant graphical representation of symmetry at atomic level and provides an overview on arrangement of electrons. It started merely as tabular representation of chemical elements, later got strengthened with quantum mechanical description of atomic structure and recent studies have revealed that periodic table can be formulated using SO(4,2) SU(2) group. IUPAC, the governing body in Chemistry, doesn‟t approve any periodic table as a standard periodic table. The only specific recommendation provided by IUPAC is that the periodic table should follow the 1 to 18 group numbering. In this technical paper, we describe a new graphical representation of periodic table, referred as „Circular form of Periodic table‟. The advantages of circular form of periodic table over other representations are discussed along with a brief discussion on history of periodic tables. 1. Introduction The profoundness of inherent symmetry in nature can be seen at different depths of atomic scales. Periodic table symbolizes one such elegant symmetry existing within the atomic structure of chemical elements. This so called „symmetry‟ within the atomic structures has been widely studied from different prospects and over the last hundreds years more than 700 different graphical representations of Periodic tables have emerged [1]. Each graphical representation of chemical elements attempted to portray certain symmetries in form of columns, rows, spirals, dimensions etc. Out of all the graphical representations, the rectangular form of periodic table (also referred as Long form of periodic table or Modern periodic table) has gained wide acceptance. -

Development of a Solvent Extraction Process for Group Actinide Recovery from Used Nuclear Fuel

THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Development of a Solvent Extraction Process for Group Actinide Recovery from Used Nuclear Fuel EMMA H. K. ANEHEIM Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Gothenburg, Sweden, 2012 Development of a Solvent Extraction Process for Group Actinide Recovery from Used Nuclear Fuel EMMA H. K. ANEHEIM ISBN 978-91-7385-751-2 © EMMA H. K. ANEHEIM, 2012. Doktorsavhandlingar vid Chalmers tekniska högskola Ny serie Nr 3432 ISSN 0346-718X Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Gothenburg Sweden Telephone + 46 (0)31-772 1000 Cover: Radiotoxicity as a function of time for the once through fuel cycle (left) compared to one P&T cycle using the GANEX process (right) (efficiencies: partitioning from Table 5.5.4, transmutation: 99.9%). Calculations performed using RadTox [HOL12]. Chalmers Reproservice Gothenburg, Sweden 2012 Development of a Solvent Extraction Process for Group Actinide Recovery from Used Nuclear Fuel EMMA H. K. ANEHEIM Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering Chalmers University of Technology Abstract When uranium is used as fuel in nuclear reactors it both undergoes neutron induced fission as well as neutron capture. Through successive neutron capture and beta decay transuranic elements such as neptunium, plutonium, americium and curium are produced in substantial amounts. These radioactive elements are mostly long-lived and contribute to a large portion of the long term radiotoxicity of the used nuclear fuel. This radiotoxicity is what makes it necessary to isolate the used fuel for more than 100,000 years in a final repository in order to avoid harm to the biosphere. -

The Group 1A and Group 2A Elements

Cotton chapter 10,11 Group 1A Group 1A Qualitative alkali metal analysis Alkali Metals y The group 1A elements with their ns1 valence electron configurations are very active metals. They lose their valence electrons very readily. They have low ionization energies and react with nonmetals to form ionic solids. 2Na(s) +Cl2(g) Æ 2NaCl(s) y The expected trend in reducing ability, Cs>Rb>K>Na>Li y Alkali metals all react vigorously with water to release hydrogen gas. + ‐ 2M(s) +2H2O(l) Æ 2M (aq) +2OH(aq) +H2(g) y Observed reducing abilities: Li>K>Na First ionization energy Soda production Properties and Trends in Group 1A y The Group 1A metals exhibit regular trends for a number of properties. y Irregular trends suggest that factors are working against each other in determining a property (such as the density “discrepancy” between sodium and potassium). y The alkali metals have two notable physical properties: they are all soft and have low melting points. y When freshly cut, the alkali metals are bright and shiny—typical metallic properties. The metals quickly tarnish, however, as they react with oxygen in the air. Alkali Metal Oxides In the presence of ample oxygen, 4Li + O2 → 2Li2O(regularoxide) 2Na + O2 → Na2O2 (peroxide) K+O2 → KO2 (superoxide) Rb + O2 → RbO2 (superoxide) Cs + O2 → CsO2 (superoxide) The oxides of Group 1A Direct reaction of the alkali metals with O2 gives : Li ‐> oxide, peroxide (trace) Na ‐> peroxide , oxide (trace) K,Rb,Cs ‐> superoxide Diagonal Relationships: The Special Case of Lithium In some of its properties, lithium and its compounds resemble magnesium and its compounds. -

Where Is Water on the Periodic Table

Where Is Water On The Periodic Table Grum Jess regrown some tirls and risk his creepies so ambrosially! Roderigo is edaphic: she libel ahold and budges her barm. Corrugate and percipient Ford never digitized lickerishly when Janos literalising his ultrafilter. Unsubscribe from rivers from three particles in marah was it is where water on the periodic table The periodic tables is where compounds is a question yourself. Periodic table organized his element does not the water where is on oxygen and silicon does the universe and the sight of concentration and. In the marine environment. The table is where it is generally halogens are. An appreciation of water resources, data for gym, make tungsten gets very sophisticated pieces of oxo anions. Tcp connection time is table is on the water periodic. In the 9th century BC a Spartan lawgiver invented a drinking cup that could go mud stick missing its turn Later on the posture of medicine Hippocrates developed a device called the Hippocrates Sleeve a cloth bag weight was used to strain boiled rain water eliminating hoarseness and even smell. His law that is an apartment building large version of a ratio of where water was given element in open a pond would accumulate at an outer shells need. On their properties? Free 2-day shipping Buy Chemistry Elements Pet Mat the Food make Water Periodic Table of Elements in Green Shades Education Themed Non-Slip Rubber. The wall of the cell is the plasma membrane that controls the rate and type of ions and molecules passing into and out of the cell. -

Of the Periodic Table

of the Periodic Table teacher notes Give your students a visual introduction to the families of the periodic table! This product includes eight mini- posters, one for each of the element families on the main group of the periodic table: Alkali Metals, Alkaline Earth Metals, Boron/Aluminum Group (Icosagens), Carbon Group (Crystallogens), Nitrogen Group (Pnictogens), Oxygen Group (Chalcogens), Halogens, and Noble Gases. The mini-posters give overview information about the family as well as a visual of where on the periodic table the family is located and a diagram of an atom of that family highlighting the number of valence electrons. Also included is the student packet, which is broken into the eight families and asks for specific information that students will find on the mini-posters. The students are also directed to color each family with a specific color on the blank graphic organizer at the end of their packet and they go to the fantastic interactive table at www.periodictable.com to learn even more about the elements in each family. Furthermore, there is a section for students to conduct their own research on the element of hydrogen, which does not belong to a family. When I use this activity, I print two of each mini-poster in color (pages 8 through 15 of this file), laminate them, and lay them on a big table. I have students work in partners to read about each family, one at a time, and complete that section of the student packet (pages 16 through 21 of this file). When they finish, they bring the mini-poster back to the table for another group to use. -

Elements Make up the Periodic Table

Page 1 of 7 KEY CONCEPT Elements make up the periodic table. BEFORE, you learned NOW, you will learn • Atoms have a structure • How the periodic table is • Every element is made from organized a different type of atom • How properties of elements are shown by the periodic table VOCABULARY EXPLORE Similarities and Differences of Objects atomic mass p. 17 How can different objects be organized? periodic table p. 18 group p. 22 PROCEDURE MATERIALS period p. 22 buttons 1 With several classmates, organize the buttons into three or more groups. 2 Compare your team’s organization of the buttons with another team’s organization. WHAT DO YOU THINK? • What characteristics did you use to organize the buttons? • In what other ways could you have organized the buttons? Elements can be organized by similarities. One way of organizing elements is by the masses of their atoms. Finding the masses of atoms was a difficult task for the chemists of the past. They could not place an atom on a pan balance. All they could do was find the mass of a very large number of atoms of a certain element and then infer the mass of a single one of them. Remember that not all the atoms of an element have the same atomic mass number. Elements have isotopes. When chemists attempt to measure the mass of an atom, therefore, they are actually finding the average mass of all its isotopes. The atomic mass of the atoms of an element is the average mass of all the element’s isotopes. -

On a Group-Theoretical Approach to the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements Maurice Kibler

On a group-theoretical approach to the periodic table of chemical elements Maurice Kibler To cite this version: Maurice Kibler. On a group-theoretical approach to the periodic table of chemical elements. Jun 2004, Prague. hal-00002554 HAL Id: hal-00002554 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00002554 Submitted on 16 Aug 2004 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. On a group-theoretical approach to the periodic table of chemical elements Maurice R. Kibler Institut de Physique Nucl´eaire de Lyon IN2P3-CNRS et Universit´eClaude Bernard 43 Bd du 11 Novembre 1918, F-69622 Villeurbanne Cedex, France This paper is concerned with the application of the group SO(4, 2)⊗SU(2) to the periodic table of chemical elements. It is shown how the Madelung rule of the atomic shell model can be used for setting up a periodic table that can be further rationalized via the group SO(4, 2)⊗SU(2) and some of its subgroups. Qualitative results are obtained from the table and the general lines of a programme for a quantitative approach to the properties of chemical elements are developed on the basis of the group SO(4, 2)⊗SU(2). -

Periodic Table of the Elements Notes

Periodic Table of the Elements Notes Arrangement of the known elements based on atomic number and chemical and physical properties. Divided into three basic categories: Metals (left side of the table) Nonmetals (right side of the table) Metalloids (touching the zig zag line) Basic Organization by: Atomic structure Atomic number Chemical and Physical Properties Uses of the Periodic Table Useful in predicting: chemical behavior of the elements trends properties of the elements Atomic Structure Review: Atoms are made of protons, electrons, and neutrons. Elements are atoms of only one type. Elements are identified by the atomic number (# of protons in nucleus). Energy Levels Review: Electrons are arranged in a region around the nucleus called an electron cloud. Energy levels are located within the cloud. At least 1 energy level and as many as 7 energy levels exist in atoms Energy Levels & Valence Electrons Energy levels hold a specific amount of electrons: 1st level = up to 2 2nd level = up to 8 3rd level = up to 8 (first 18 elements only) The electrons in the outermost level are called valence electrons. Determine reactivity - how elements will react with others to form compounds Outermost level does not usually fill completely with electrons Using the Table to Identify Valence Electrons Elements are grouped into vertical columns because they have similar properties. These are called groups or families. Groups are numbered 1-18. Group numbers can help you determine the number of valence electrons: Group 1 has 1 valence electron. Group 2 has 2 valence electrons. Groups 3–12 are transition metals and have 1 or 2 valence electrons. -

Atomic Weights and Isotopic Abundances*

Pure&App/. Chem., Vol. 64, No. 10, pp. 1535-1543, 1992. Printed in Great Britain. @ 1992 IUPAC INTERNATIONAL UNION OF PURE AND APPLIED CHEMISTRY INORGANIC CHEMISTRY DIVISION COMMISSION ON ATOMIC WEIGHTS AND ISOTOPIC ABUNDANCES* 'ATOMIC WEIGHT' -THE NAME, ITS HISTORY, DEFINITION, AND UNITS Prepared for publication by P. DE BIEVRE' and H. S. PEISER2 'Central Bureau for Nuclear Measurements (CBNM), Commission of the European Communities-JRC, B-2440 Geel, Belgium 2638 Blossom Drive, Rockville, MD 20850, USA *Membership of the Commission for the period 1989-1991 was as follows: J. R. De Laeter (Australia, Chairman); K. G. Heumann (FRG, Secretary); R. C. Barber (Canada, Associate); J. CCsario (France, Titular); T. B. Coplen (USA, Titular); H. J. Dietze (FRG, Associate); J. W. Gramlich (USA, Associate); H. S. Hertz (USA, Associate); H. R. Krouse (Canada, Titular); A. Lamberty (Belgium, Associate); T. J. Murphy (USA, Associate); K. J. R. Rosman (Australia, Titular); M. P. Seyfried (FRG, Associate); M. Shima (Japan, Titular); K. Wade (UK, Associate); P. De Bi&vre(Belgium, National Representative); N. N. Greenwood (UK, National Representative); H. S. Peiser (USA, National Representative); N. K. Rao (India, National Representative). Republication of this report is permitted without the need for formal IUPAC permission on condition that an acknowledgement, with full reference together with IUPAC copyright symbol (01992 IUPAC), is printed. Publication of a translation into another language is subject to the additional condition of prior approval from the relevant IUPAC National Adhering Organization. ’Atomic weight‘: The name, its history, definition, and units Abstract-The widely used term “atomic weight” and its acceptance within the international system for measurements has been the subject of debate. -

Periodic Table 1 Periodic Table

Periodic table 1 Periodic table This article is about the table used in chemistry. For other uses, see Periodic table (disambiguation). The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers (numbers of protons in the nucleus), electron configurations , and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, which is typically listed with the chemical symbol in each box. The standard form of the table consists of a grid of elements laid out in 18 columns and 7 Standard 18-column form of the periodic table. For the color legend, see section Layout, rows, with a double row of elements under the larger table. below that. The table can also be deconstructed into four rectangular blocks: the s-block to the left, the p-block to the right, the d-block in the middle, and the f-block below that. The rows of the table are called periods; the columns are called groups, with some of these having names such as halogens or noble gases. Since, by definition, a periodic table incorporates recurring trends, any such table can be used to derive relationships between the properties of the elements and predict the properties of new, yet to be discovered or synthesized, elements. As a result, a periodic table—whether in the standard form or some other variant—provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical behavior, and such tables are widely used in chemistry and other sciences. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table. -

Synthesis and Evaluation of New Polyfunctional Molecules for the Group Actinide Separation

P1_13 Synthesis and Evaluation of new Polyfunctional Molecules for the Group Actinide Separation Cécile Marie, Manuel Miguirditchian, Denis Guillaneux, Didier Dubreuil, Virginie Blot, Muriel Pipelier Université de Nantes, CNRS, Laboratoire de Synthèse Organique, UMR 6513, Faculté des Sciences et des Techniques, 2 rue de la Houssinière, BP 92208 44322 Nantes Cedex 3, France CEA-Valrhô, DEN/DRCP/SCPS, B.P. 17171, 30207 Bagnols-sur-Cèze Cedex, France [email protected] INTRODUCTION and +VI (U, Np, Pu). The idea (Figure 2) is to combine a hard site (the amide function) to The aim of this project is to synthesize new extract actinides from high acidity (U, Np et Pu) extracting molecules for the grouped actinide and a soft site (the polyaromatic unit) to separation. These extractants will have to satisfy discriminate lanthanides (III) from actinides specifications imposed by the GANEX process (III). (Group Actinide Extraction). This new concept is an option for the homogeneous reprocessing of Generation IV spent fuels. All actinides Pyridino-Pyridazine (uranium, neptunium, plutonium, americium and unit curium) will be extracted together using solvent extraction and separated from the fission An3+ Amide products in order to recycle them after nuclear function fuel re-fabrication (Figure 1). Fig. 2. Bifunctional molecules. Spent fuel Fuel Some ligands have already shown interesting Re-fabrication selectivities for the extraction of actinides but at DISSOLUTION GANEX PROCESS low acidity (HNO3 0,01 M) [1]. The introduction of amidoalkyl groups on these Uranium U SEPARATION structures improved their lipophily. Their εU +Pu+Np+Am+Cm extracting performances are actually tested on Actinides multi-elementary actinide solutions. -

Platinum Group Metal Chalcogenides

Platinum Group Metal Chalcogenides THEIR SYNTHESES AND APPLICATIONS IN CATALYSIS AND MATERIALS SCIENCE By Sandip Dey and Vimal K. Jain* Novel Materials and Structural Chemistry Division, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Mumbai 400085, India * E-mail: [email protected] Some salient features of platinum group metal compounds with sulfur, selenium or tellurium, known as chalcogenides, primarily focusing on binary compounds, are described here. Their structural patterns are rationalised in terms of common structural systems. Some applications of these compounds in catalysis and materials science are described, and emerging trends in designing molecular precursors for the syntheses of these materials are highlighted. Chalcogenides are a range of compounds that will consider first a selection of the structures primarily contain oxygen, sulfur, selenium, telluri- adopted, followed by their catalytic and electronic um or polonium and which may also occur in uses. nature. The compounds may be in binary, ternary or quaternary form. Platinum group metal chalco- Ruthenium and Osmium genides have attracted considerable attention in Chalcogenides recent years due to their relevance in catalysis and Ruthenium and osmium dichalcogenides of materials science. Extensive application of palladi- composition ME2 (M = Ru, Os; E = S, Se, Te) are um (~ 27% of global production in year 2000) in usually prepared by heating stoichiometric quanti- the electronic industry in multilayer ceramic capac- ties of the elements in evacuated sealed ampoules itors (MLCCs) and ohmic contacts has further at elevated temperatures (~ 700ºC) (13). Single accelerated research activity on platinum group crystals, such as RuS2, see Figure 1, are grown metal chalcogenide materials. either from a tellurium flux (4) or by chemical The platinum group metals form several vapour transport techniques using interhalogens as chalcogenides: transporting agent (5).