Waldron Vs. Smith: Shipwreck at the Eastward, 1671

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Settlement-Driven, Multiscale Demographic Patterns of Large Benthic Decapods in the Gulf of Maine

Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, L 241 (1999) 107±136 Settlement-driven, multiscale demographic patterns of large benthic decapods in the Gulf of Maine Alvaro T. Palmaa,* , Robert S. Steneck b , Carl J. Wilson b aDepartamento EcologõaÂÂ, Ponti®cia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Alameda 340, Casilla 114-D, Santiago, Chile bIra C. Darling Marine Center, School of Marine Sciences, University of Maine, Walpole, ME 04573, USA Received 3 November 1998; received in revised form 30 April 1999; accepted 5 May 1999 Abstract Three decapod species in the Gulf of Maine (American lobster Homarus americanus Milne Edwards, 1837, rock crab Cancer irroratus Say, 1817, and Jonah crab Cancer borealis Stimpson, 1859) were investigated to determine how their patterns of settlement and post-settlement abundance varied at different spatial and temporal scales. Spatial scales ranged from centimeters to hundreds of kilometers. Abundances of newly settled and older (sum of several cohorts) individuals were measured at different substrata, depths, sites within and among widely spaced regions, and along estuarine gradients. Temporal scales ranged from weekly censuses of new settlers within a season to inter-annual comparisons of settlement strengths. Over the scales considered here, only lobsters and rock crabs were consistently abundant in their early post- settlement stages. Compared to rock crabs, lobsters settled at lower densities but in speci®c habitats and over a narrower range of conditions. The abundance and distribution of older individuals of both species were, however, similar at all scales. This is consistent with previous observations that, by virtue of high fecundity, rock crabs have high rates of settlement, but do not discriminate among habitats, and suffer high levels of post-settlement mortality relative to lobsters. -

History of Maine - History Index - MHS Kathy Amoroso

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 2019 History of Maine - History Index - MHS Kathy Amoroso Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Amoroso, Kathy, "History of Maine - History Index - MHS" (2019). Maine History Documents. 220. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory/220 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Index to Maine History publication Vol. 9 - 12 Maine Historical Society Newsletter 13 - 33 Maine Historical Society Quarterly 34 – present Maine History Vol. 9 – 51.1 1969 - 2017 1 A a' Becket, Maria, J.C., landscape painter, 45:203–231 Abandonment of settlement Besse Farm, Kennebec County, 44:77–102 and reforestation on Long Island, Maine (case study), 44:50–76 Schoodic Point, 45:97–122 The Abenaki, by Calloway (rev.), 30:21–23 Abenakis. see under Native Americans Abolitionists/abolitionism in Maine, 17:188–194 antislavery movement, 1833-1855 (book review), 10:84–87 Liberty Party, 1840-1848, politics of antislavery, 19:135–176 Maine Antislavery Society, 9:33–38 view of the South, antislavery newspapers (1838-1855), 25:2–21 Abortion, in rural communities, 1904-1931, 51:5–28 Above the Gravel Bar: The Indian Canoe Routes of Maine, by Cook (rev.), 25:183–185 Academy for Educational development (AED), and development of UMaine system, 50(Summer 2016):32–41, 45–46 Acadia book reviews, 21:227–229, 30:11–13, 36:57–58, 41:183–185 farming in St. -

Boothbay Harbor

BOOTHBAY 2019 GUIDE TO THE REGION HARBOR ON THE WATER LIGHTHOUSES SHOPPING FOOD & DINING THINGS TO DO ARTS & CULTURE PLACES TO STAY EVENTS BOOTHBAYHARBOR.COM OCEAN POINT INN RESORT Oceanfront Inn, Lodge, Cottages & Dining Many rooms with decks • Free WiFi Stunning Sunsets • Oceanfront Dining Heated Outdoor Pool & Hot Tub Tesla & Universal Car Chargers 191 Shore Rd, East Boothbay, ME | 207.633.4200 | Reservations 800.552.5554 www.oceanpointinn.com SCHOONER EASTWIND Boothbay Harbor SAILING DAILY MAY - OCTOBER www.schoonereastwind.com • (207)633-6598 EXPLORE THIS BEAUTIFUL PART OF MAINE. Boothbay • Boothbay Harbor • Damariscotta East Boothbay • Edgecomb • Lincolnville • Monhegan Newcastle • Rockport • Southport • Trevett • Waldoboro Westport • Wiscasset • Woolwich Learn more at BoothbayHarbor.com 2 Follow us on 3 WELCOME TO THE BOOTHBAY HARBOR REGION & MIDCOAST MAINE! CONTENTS Just 166 miles north of Boston and a little over an hour north of Portland, you’ll find endless possibilities of things to see and do. Whether you’re in Maine for a short visit, a summer, or a lifetime, the Boothbay Harbor and Midcoast regions are uniquely special for everyone. This guide is chock full of useful information - where to shop, dine, stay, and play - and we encourage you to keep a copy handy at all times! It’s often referred to as the local phone book! Here are some things you can look forward to when you visit: • Boating, kayaking, sailing, sport fishing, and windjammer cruises • Locally farm-sourced foods, farmers markets, lobsters, oysters, wineries, and craft breweries TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................. 5 THINGS TO DO ........................................ 52 • A walkable sculpture trail, art galleries galore, and craft fairs Attractions.. -

Classification of Estuarine and Marine Waters

38 §469. CLASSIFICATIONS OF ESTUARINE AND MARINE WATERS 38 §469. CLASSIFICATIONS OF ESTUARINE AND MARINE WATERS 1. Cumberland County. All estuarine and marine waters lying within the boundaries of Cumberland County and that are not otherwise classified are Class SB waters. A. Cape Elizabeth. (1) Tidal waters of the Spurwink River system lying north of a line at latitude 43`-33'-44" N. - Class SA. [1989, c. 764, §22 (AMD).] B. Cumberland. (1) Tidal waters located within a line beginning at a point located on the Cumberland-Portland boundary at approximately latitude 43`41'-18"N., longitude 70` - 05'-48"W. and running northeasterly to a point located on the Cumberland-Harpswell boundary at approximately latitude 43` - 42'-57"N., longitude 70` - 03'-50" W.; thence running southwesterly along the Cumberland- Harpswell boundary to a point where the Cumberland, Harpswell and Portland boundaries meet; thence running northeasterly along the Cumberland-Portland boundary to point of beginning - Class SA. [1985, c. 698, §15 (NEW).] C. Falmouth. (1) Tidal waters of the Town of Falmouth located westerly and northerly, to include the Presumpscot estuary, of a line running from the southernmost point of Mackworth Island; thence running northerly along the western shore of Mackworth Island and the Mackworth Island Causeway to a point located where the causeway joins Mackworth Point - Class SC. [1999, c. 277, §25 (AMD).] D. Harpswell. (1) Tidal waters located within a line beginning at a point located on the Cumberland-Harpswell boundary at approximately -

Archaeology of the Cod Fishery: Damariscove Island

ALARIC FAULKNER Besides supplying fish for export , these men were to keep the island "farmed out in Sir Ferdinando's name to such as shall there fish. " For their protec Archaeology of the Cod Fishery: tion against the French and Indians , they had built "a strong palisado of spruce trees of some ten feet Damariscove Island high, having besides their small shot, one piece of ordnance and some ten good dogs" (James 1963:15-16). With the hope of learning more of ABSTRACT this occupation and its successors, the author di In the 17th and 18th centuries, seasonal fishermen from rected an intensive survey of Damariscove in the France and England practiced nearly identical methods of summers of 1979 and 1980, sponsored by the dry curing codfish on the coasts of North America. The Maine Historic Preservation Commission. The complex measures taken in cleaning , salting and drying the documentary and archaeological research at this cod were followed with ritual fidelity. The well-preserved and related fishing stations in Maine has led him to product was exported to the warmer climates of the Antilles and Mediterranean where it found a ready market. Structures examine the archaeology of the cod fishery in for this land based operation were rebuilt annually, each general. camp requiring a vast area of drying racks and a specific set As it was the lure of the cod fishery which of wattle walled buildings, roofed with bark and sod or else brought Europeans to the Northeast, the history covered by the ship's sails. These structures should leave and archaeology of this industry should be of diagnostic post mold configurations. -

Ancient Dominions of Maine

Glass. Book- ANCIENT DOMINIOiNS OF MAINE, EMBRACING THE EARLIEST FACTS, THE RECENT DISCOVERIES OP THE REMAINS OF ABORIGINAL TOWNS, THE VOYAGES, SETTLEMENTS, BAT- TLE SCENES, AND INCIDENTS OF INDIAN WARFARE, AND OTHER INCIDENTS OF HISTORY, TOGETHER WITH THE RELIGIOUS DEVELOPMENTS OP SOCIETY WITHIN THE ANCIENT SAGADAHOC, SHEEPSCOT AND PEMAQUID PRE- CINCTS AND DEPENDENCIES. « By RUFUS king SEWALL, author of sketches of the city of st. augustine. B ATH : ELISHA CLARK AND COMPANY. BOSTON, MASS.: CROSBY AND NICHOLS. PORTLAND: SANBORN AND CARTER. 185D, Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1859, by II. K. S EWALL, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the District of Maine. STEREOTYrED AND PRINTED' B'V 3. TUURSTON, PORTLAND, ME. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. ANTE-COLONIAL PKRIOD. Historical remains — Location — Pedcokcgowake — Antiquity of the relics — Remains of Nekrangan — Local features — Human remains — Observations — Exhumations — White Mountain views — Colonial ves- tiges — Suggestive features of the remains — Ruins accounted for — Norumbcgua — Historical view of the name — Locality — Personal ap- pearance of the ante-colonial inhabitants — "Weapons — Capital of the country — Court costume — Weymouth's treachery — Whale fishery at Pemaquid — Damariscotta, seat of ante-colonial empire — Aboriginal names — Arambec — Menikuk — Race inhabiting these cities — Succes- sion of races — Druidical suggestions — The Bashaba — His enemies — Wawennocks — Their end, . 13 CHAPTER IL PERIOD OF DISCOVERY. Gosnold at Kennebec — Bark Shallop — -

Dedication to Bill Danforth

The Friendship Sloop Society's 44th Annual Regatta ROCKLAND-THOMASTON AREA CHAMBER OF COMMERCE BURNHAM WELCOMES BOAT THE FRIENDSHIP SLOOP SOCIETY BUILDING TO & ROCKLAND, MAINE DESIGN July 27-29 11 BURNHAM COURT, P.O. BOX 541 Join the Friendship Sloop Society members for a public supper and free entertainment on Wednesday. The public is also welcome to ESSEX, MA 01929 attend breakfasts and skippers' meetings each morning, and visit (978) -768-2569 sloops dockside at the Public Landing. There will be races each day, and a parade of sloops on Wednesday (see page 4 for a full schedule). OR SEE OUR WEBSITE: OTHER SUMMER EVENTS burnhamboatbuilding.com July 4 Thomaston 4th of July TRADITIONAL WOODEN BOATS FOR COMMERCIAL PASSENGER July 10-11 North Atlantic Blues Festival AND PLEASURE USE August 4-8 IN ADDITION TO NEW BOATS WE Maine Lobster Festival www.mainelobsterfestival.com PROVIDE FRIENDS AND FRIENDSHIPS For more information on the area, contact the WITH NAUTICAL CONSULTING, AND Rockland-Thomaston Area Chamber of Commerce SHIPS TIMBER AS WELL AS P.O. Box 508 • Rockland, ME 04841 1-800-562-2529 or 207-596-0376 TRADITIONAL SAILS, SPARS E-mail: infotherealmaine.com • Web Site: http://www.therealmaine.com AND RIGGING Friendship Sloop Society Officers 2004 During the deep freeze of January 2004, the Executive Committee of the Friendship Sloop Society set out to secure the longevity of our fine organization. Each Committee member was given the names of approximately 20 sloop owners to survey. The purpose of the survey was to: • Connect with our membership • Learn what it is that keeps members coming back to events each year, or Commodore John B. -

COASTAL WATERBIRD COLONIES: by Carl E. Korschgen HJS/OBS-79

HJS/OBS-79/09 September 1979 COASTAL WATERBIRD COLONIES: ~1AINE The Biological Services Program was established within the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to supply scientific information and methodologies on key envi ronmenta 1 issues that impact fi sh and wildl i fe resources and thei r supporting ecosystems. The mission of the program is as follows: by • To. strengthen the Fish. andVJi TdltfEi .c~ in its role as a prima ry*purceof .inforrnil.ti 1 fish and wild 1i fe.. resour!:es~.parti culilrly ·"",c,nA,.t-· tQeriyi ronmenta 1 Carl E. Korschgen impact ass es.smel'l~.. Maine Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit 240 Nutting Hall • University of Maine Orono, ME 04469 Contract No. 14-16-0008-1189 I nformat) o.rt for use in thepla the impact of·devel techni.cal assistanceSElrv . sare based on an analysis of the issues a determination of the decisionmakers involved and their information needs, Project Officer and. an evaluationdofthe state of the art to identify information gaps Ralph Andrews and to determine priorities. This is a strategy that will ensure that U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service the products produced and disseminated are timely and useful. One Gateway Center, Suite 700 Projects have been initiated in the following areas: coal extraction Newton Corner, MA 02158 and conversion; power plants; geothermal, mineral and oil shale develop~ ment; water resource analysis, including stream alterations and western water allocation; coastal ecosystems and Outer C.ontinenta1 Shelf develop ment; and systems inventory, including National Wetland Inventory, habitat classification and analysis, and information transfer. A contribution of the Maine Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, The Bio1 ogi ca lS.ervi ces Programco~slsts()f the. -

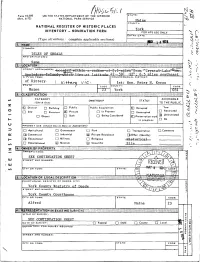

NOMINATION FORM York for NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Continuation Sheet) •AY 1 Fi 1974 (Number All Entries)

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE „ . Xl COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORI C PLACES York INVENTORY - NOMINATION F UKM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicabh 3sec"°"iv MAY 16W4 COMMON: ISLES OF SHOALS AND/OR HISTORIC: Same !iS|:;S:£*:!;|i-::j;^ STREET AND NUMBER: -tiO-CErCeuT_-. ^-rip J..T.J, WTtTttli,.,4_i.t.,J . — fct, — L<£Q. , , 1 iiis-of— 2r5"-mrl-erg~f rom -" Crys tai—Lake-^-on^ M 'Ap pied&re—T'si'antiT—^tiip.?! ~ -1 iV « • -a t 1 at itiid«>v..42-59J" '-12",* 6.5 miles southeast CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: of Kittery. (_ &++&+* i/ic. 1st: Hon. Peter N. Kvros STATE / CODE COUNTY: CODE Maine ^J York: 031 |$i|(Vf?:£&i? ¥ii'i't*'jF'&'i/\ti y '• ]- : '''"' ^ ''-'• ''' '•''••••••'•'••''•''• : - V &¥&••''• V:'Xf ••'••&•'•': •?•:• ':':: : : : •:•:••>: 'f •:•••.'•:'••: ••:• ':•; lllillllil;llllllllllllllilllili::il!lllliPlll^lt:'||i|l!ll||l 1/1 CATEGORY OWNER SHIP < STATUS ACCESSIBLE (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC E District Q Building CD Public Public Acquisition: |T] Occupied Yes: n Site Q Structure S Private C 1 In Process r-, Unoccupied D R^tricted D Object D Both C3 Being Considered ^ p reservatjon work 3 Unrestricted in progress ' — ' u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) FT! Agricultural | | Government Q Park I 1 Transportation D Comments OH (3 Commercial CD Industrial gj] Priva te Residence (jjj: Other (Specify) S Educational l~1 Mi itary Q Relig ious His t or i p alr 1 | Entertainment Ixl Museum (^) Scien tific Sit*3 } OWNER'S -

The Story of Pemaquid

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 2019 History of Pemaquid Maine - The tS ory of Pemaquid James Otis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Otis, James, "History of Pemaquid Maine - The tS ory of Pemaquid" (2019). Maine History Documents. 254. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory/254 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIONEER TOWNS OF AMERICA THE STORY OF PEMAQUID BY J A M E S OT I S I,/':: · ; '· AV"rBOa 011 " T1111 SroaY 011 OLD FALIIOUTH". NEW YORK: THOMAS Y. CROWELL & CO. PUBUSHERS COPYRIGHT, 190'2, BY T. Y. CROWELL & CO, TYPooBAPHY BY 0. J. PBTBBS & 8olll', BOSTON, U,S,A, NOTE. IN this story, the second in the series of "Pioneer Towns of America," Pemaquid Plan t.ation has been chosen as the central point, because, during the early settlement of Maine, it was the most important post on the coast east of Massachusetta. / To those brave men who strove to build ..bo��s in the vicinity of Pemaquid are we es pecially indebted for their bold battling against civilized as well as savage foes, their sturdy fight against the forces of nature, and their indomit.able courage, so often and so sorely tried. '.., ...,, 8 - > 190963 CONTENTS. P.A&B The First White Men 7 The Archangel 10 The Indians 12 The First Captives • 14 The First Settlement 16 Captain John Smith • 19 New Settlements • 22 Royal Grants • . -

Boothbay Harbor Region & Midcoast Maine!

BOOTHBAY 2020-2021 VISITOR GUIDE HARBOR The Boating Capitol of New England Life on the Water – Shopping – Food & Dining Things to Do – Places to Stay – Events BOOTHBAYHARBOR.COM WELCOME TO THE BOOTHBAY HARBOR REGION & MIDCOAST MAINE! Just 166 miles north of Boston and a little over an hour north of Portland, you’ll find endless possibilities of things to see and do. Whether you’re in Maine for a short visit, a summer, or a lifetime, the Boothbay Harbor and Midcoast regions are uniquely special for everyone. This guide is chock full of useful information - where to shop, dine, stay, and play - and we encourage you to keep a copy handy at all times! Here are some things you can look forward to when you visit: • Boating, kayaking, sailing, sport fishing, and windjammer cruises • Locally farm-sourced foods, farmers markets, lobsters, oysters, wineries, and craft breweries • A walkable sculpture trail, art galleries galore, and craft fairs • Spectacular nature preserves, parks, lakes, and beaches • Museums, lighthouses, forts, and historic sites • Concerts, bands, movies, and live theater performances • World-class golf, pickleball, and tennis Here are some recent accolades: • Lonely Planet named Midcoast Maine one of the Top Ten Destinations in the United States. • New England Today named Boothbay Harbor one of the Top Ten Prettiest Coastal Towns in Maine. • Coastal Living Magazine named the Boothbay Region as one the Top Five Peninsulas for the Ultimate Maine Road Trip. For close to 60 years, the Boothbay Region Chamber of Commerce has been an organization whose membership is comprised of business entities and friends of the Chamber in our local communities. -

The Newfoundland Plantation in the Seventeenth Century Peter E

Fish into Wine Fish the newfoundland plantation in the seventeenth century peter e. pope Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, by the University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London into Wine The Omohundro © 2004 The University of North Carolina Press Institute of Early All rights reserved Set in Monticello type American History by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America and Culture is sponsored jointly Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data by the College of Pope, Peter Edward, 1946– Fish into wine : the Newfoundland plantation in the William and Mary seventeenth century / Peter E. Pope. p. cm. and the Colonial Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-8078-2910-2 (alk. paper) — Williamsburg isbn 0-8078-5576-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Newfoundland and Labrador—Social life and customs— Foundation. On 17th century. 2. Newfoundland and Labrador—Economic conditions—17th century. 3. Plantation life—Newfoundland November 15, 1996, and Labrador—History—17th century. 4. Frontier and the Institute adopted pioneer life—Newfoundland and Labrador. 5. English— Newfoundland and Labrador—History—17th century. the present name in 6. Cod fisheries—Newfoundland and Labrador—History— 17th century. 7. Land settlement—Newfoundland and honor of a bequest Labrador—History—17th century. 8. Newfoundland and Labrador—Emigration and immigration—History—17th from Malvern H. century. 9. England—Emigration and immigration— History—17th century. I. Omohundro Institute of Early Omohundro, Jr. American History & Culture. II. Title. f1123.p66 2004 971.8'01—dc22 2004002521 The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.