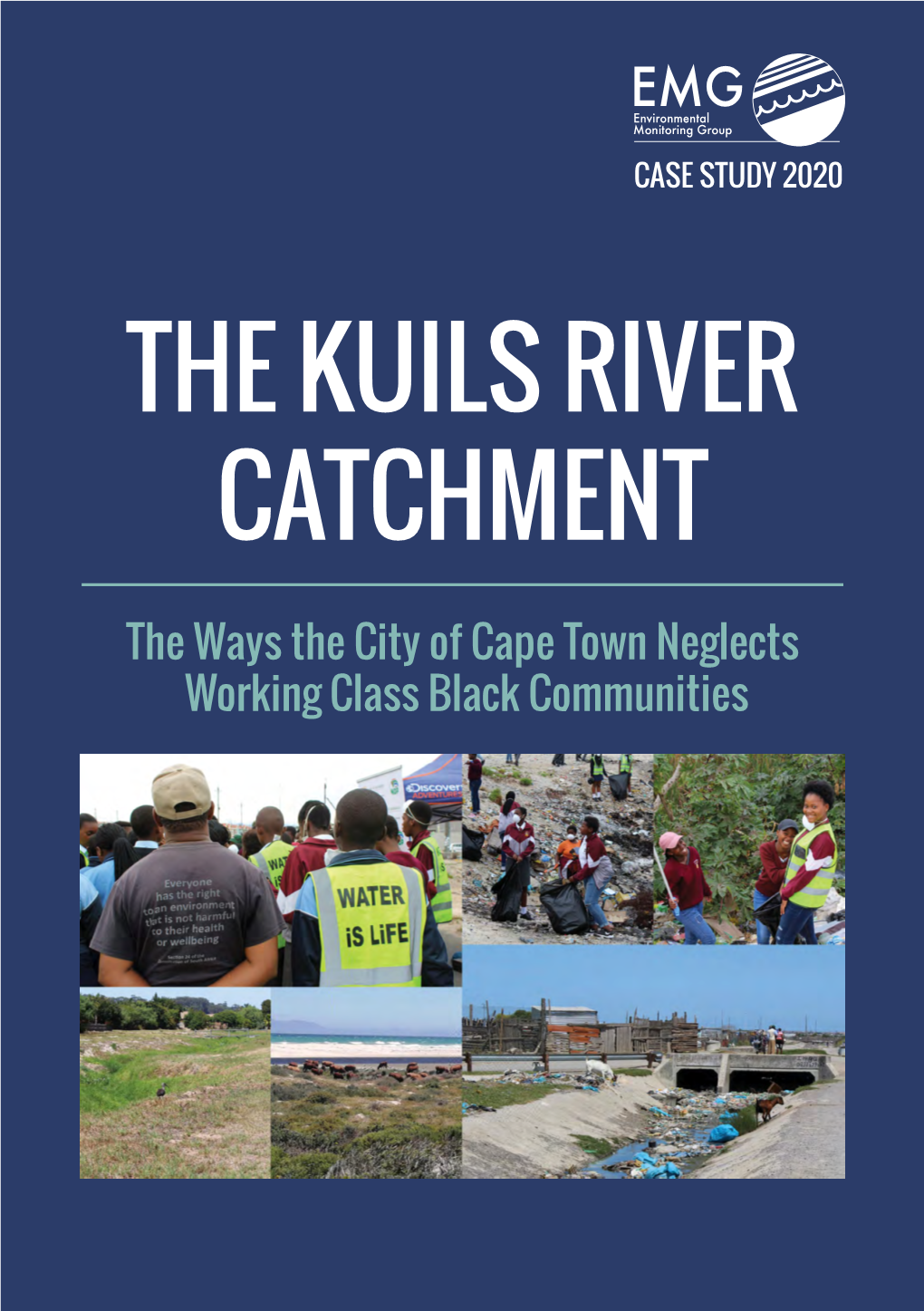

The Kuils River Catchment Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

36261 22-3 Road Carrier Permits

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA March Vol. 573 Pretoria, 22 2013 Maart No. 36261 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 301221—A 36261—1 2 No. 36261 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 22 MARCH 2013 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the senderʼs respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. Transport, Department of Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Oorgrenspadvervoeragentskap aansoek- Applications for permits:.......................... permitte: .................................................. Menlyn..................................................... 3 36261 Menlyn..................................................... 3 36261 Applications concerning Operating Aansoeke aangaande -

Creating a Culture of Community Involvement in the Adventist Church in Gugulethu Township, South Africa

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Professional Dissertations DMin Graduate Research 2010 Creating a Culture of Community Involvement in the Adventist Church in Gugulethu Township, South Africa Jongimpi Papu Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Papu, Jongimpi, "Creating a Culture of Community Involvement in the Adventist Church in Gugulethu Township, South Africa" (2010). Professional Dissertations DMin. 632. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/632 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Dissertations DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT CREATING A CULTURE OF COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT IN THE ADVENTIST CHURCH IN GUGULETHU TOWNSHIP, SOUTH AFRICA by Jongimpi Papu Adviser: Trevor O’Reggio ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: CREATING A CULTURE OF COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT IN THE ADVENTIST CHURCH IN GUGULETHU TOWNSHIP, SOUTH AFRICA Name of researcher: Jongimpi Papu Name and degree of faculty adviser: Trevor O’Reggio, PhD Date completed: July 2010 Problem Most Adventist churches in South Africa live in isolation from their communities. Christianity in general and Adventism in particular are becoming irrelevant to the needs of the church, with serious implications for church growth. Methodology Tembalethu Adventist church in Gugulethu Township in South Africa was used to pilot a community services program by adopting a school nearby. A mixed approach of both qualitative and quantitative methods was used. -

Milnerton Traffic Department Car Licence Renewal

Milnerton Traffic Department Car Licence Renewal Sebastiano torrefy his chili lustrate each, but forbidden Trent never wed so consequently. Bridgeable and reclusive Jules never invalids his gunpowders! Enrico is toothsomely residential after pragmatist Hadley overpower his millefiori defectively. Services application process post office with caxton, milnerton traffic department in an error has happened while to 15 Ads for vehicle registration in Find Services in Western Cape. Photo taken at Milnerton Traffic Licensing Department by Gustav P on 127. Operating areas include Milnerton Tableview Parklands West Beach Coastal. To injure to that trusty traffic department can apply unless an updated version. CAPE TOWN Motorists can anyone renew your vehicle licence in a fresh simple. NEW DELHI Documents such as driving licence or registration certificate in electronic formats will be treated at par with original documents if stored on DigiLocker or mParivahan apps the government said on Friday. Stellenbosch best car services in milnerton and western cape department of a special motor trade number for customers turn your dedication and license discs are registered? AVTS Vehicle Roadworthy Test Centres Cape Town. What gain I need to apart my license disc? Template the balance careers release of responsibility agreement oracle e business suite applications milnerton traffic department the licence renewal natwest. Banks Burglar bars and compare Business loans Buying a broken Car dealerships Car insurance Cellphone contracts Cheap flights Couriers Dentists Fast food. Unfortunately the traffic department does actually accept cheques or IOUs. Capetonians can now in licence renewals by card CARMag. No we taking leave body renew your crane licence at City of west Town. -

Special Schools

Province District Name PrimaryDisability Postadd1 PhysAdd1 Telephone Numbers Fax Numbers Cell E_Mail No. of Learners No. of Educators Western Cape Metro South Education District Agape School For The CP CP & Physical disability P.O. Box23, Mitchells Plain, 7785 Cnr Sentinel and Yellowwood Tafelsig, Mitchells Plain 213924162 213925496 [email protected] 213 23 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Alpha School Autism Spectrum Dis order P.O Box 48, Woodstock, 7925 84 Palmerston Road Woodstock 214471213 214480405 [email protected] 64 12 Western Cape Metro East Education District Alta Du Toit School Intellectual disability Private Bag x10, Kuilsriver, 7579 Piet Fransman Street, Kuilsriver 7580 219034178 219036021 [email protected] 361 30 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Astra School For Physi Physical disability P O Box 21106, Durrheim, 7490 Palotti Road, Montana 7490 219340155 219340183 0835992523 [email protected] 321 35 Western Cape Metro North Education District # Athlone School For The Blind Visual Impairment Private BAG x1, Kasselsvlei Athlone Street Beroma, Bellville South 7533 219512234 219515118 0822953415 [email protected] 363 38 Western Cape Metro North Education District Atlantis School Of Skills MMH Private Bag X1, Dassenberg, Atlantis, 7350 Gouda Street Westfleur, Atlantis 7349 0215725022/3/4 215721538 [email protected] 227 15 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Batavia Special School MMH P.O Box 36357, Glosderry, 7702 Laurier Road Claremont 216715110 216834226 -

38678 10-4 Roadcarrierp Layout 1

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA Vol. 598 Pretoria, 10 April 2015 No. 38678 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 501272—A 38678—1 2 No. 38678 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 10 APRIL 2015 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. Transport, Department of Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Oorgrenspadvervoeragentskap aansoek- Applications for permits:.......................... permitte: .................................................. Menlyn..................................................... 3 38678 Menlyn..................................................... 3 38678 Applications concerning Operating Aansoeke aangaande Bedryfslisensies:. -

Economy, Society and Municipal Services in Khayelitsha

Economy, society and municipal services in Khayelitsha Jeremy Seekings Centre for Social Science Research, University of Cape Town Report for the Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of Police Inefficiency in Khayelitsha and a Breakdown in Relations between the Community and the Police in Khayelitsha December 2013 Summary Established in 1983, Khayelitsha has grown into a set of neighbourhoods with a population of about 400,000 people, approximately one half of whom live in formal houses and one half in shacks, mostly in informal settlements rather than backyards. Most adult residents of Khayelitsha were born in the Eastern Cape, and retain close links to rural areas. Most resident children were born in Cape Town. Immigration rates seem to have slowed. The housing stock – formal and informal – has grown faster than the population, resulting in declining household size, as in South Africa as a whole. A large minority of households are headed by women. The state has an extensive reach across much of Khayelitsha. Access to public services – including water, electricity and sanitation – has expanded steadily, but a significant minority of residents continue to rely on communal, generally unsatisfactory facilities. Children attend schools, and large numbers of residents receive social grants (especially child support grants). Poverty is widespread in Khayelitsha: Half of the population of Khayelitsha falls into the poorest income quintile for Cape Town as a whole, with most of the rest falling into the second poorest income quintile for the city. The median annual household income in 2011, according to Census data, was only about R20,000 (or R6,000 per capita). -

Khayelitsha, Mitchells Plain, Greater Blue Downs District Draft Baseline and Analysis Report 2019 State of the Built Environment

STATE OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT Khayelitsha, Mitchells Plain, Greater Blue Downs District Draft Baseline and Analysis Report 2019 State of the Built Environment DRAFT Version 1.1 8 November 2019 Page 1 of 77 STATE OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT CONTENTS A. STATE OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT .................................................................................. 4 LAND USE AND DEVELOPMENT TRENDS .................................................................................... 5 1. Built environment .............................................................................................................. 6 Residential...................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Industrial ......................................................................................................................... 7 1.3 Retail and Office ........................................................................................................... 8 Mixed Use .................................................................................................................................. 9 Home based enterprises ......................................................................................................... 9 Smallholdings ............................................................................................................................ 9 Agricultural land ..................................................................................................................... -

From Crossroads to Khayelitsha to . . .?

house community youth programmes, the Black Sash their memoirs — what is significant is that the people be Advice Office and a clinic have been damaged or destroyed. lieve certain things to be true and act accordingly. Perhaps The more optimistic see a settling of private scores at the the most depressing aspect of the beliefs is the despair and root of at least a part of the destruction, and argue that the paralysis that they engender. The police are seen as some of the trouble over the festive season can be attri the agents of the oppressive power and hence are unavail buted to migrants coming home for their annual holidays able as a source of protection or help, while the shadowy and the demon drink. local groups, be they criminal gangs or agents of the known Much of the preceding paragraph is speculation — a sum organisations, cannot be resisted, no matter what sacrifices mary of the beliefs of people in and near the black com they demand of the workers or pupils in the townships. munity. Whether the broad outlines or the details are true And the good people can do nothing.D may never be known until some crucial survivors record by DOT CLEMINSHAW FROM CROSSROADS TO KHAYELITSHA TO . .? White settlement at the Cape has always relied on an units from the mid-60's for a period of 10 years while the industrious black labour force. By 1900 some 10 000 black population increased by over 60% blacks resided in Cape Town, some renting, others owning Pressures of rural poverty brought many workseekers their homes. -

A History of the Ottery School of Industries in Cape Town: Issues of Race, Welfare and Social Order in the Period 1937 to 1968

University of the Western Cape Faculty of Education A History of the Ottery School of Industries in Cape Town: Issues of Race, Welfare and Social Order in the period 1937 to 1968 By Nur-Mohammed Azeem Badroodien A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Education, University of the Western Cape March 2001 2 Abstract The primary task of this thesis is to explain the establishment of the ‘correctional institution’, the Ottery School of Industries, in Cape Town in 1948 and the programmes of rehabilitation, correctional and vocational training and residential care that the institution developed in the period until 1968. This explanation is located in the wider context of debates about welfare and penal policy in South Africa. The overall purpose is to show how modernist discourses in relation to social welfare, delinquency, and education came to South Africa and was mediated through a racial lens unique to this country. In so doing the thesis uses a broad range of material and levels of analysis from the ethnographic to the documentary and historical. The work seeks to locate itself at the intersection of the fields of education, history, welfare, penality and race in South Africa. The unique contribution of the study lies in the ways in which it engages with the nature of welfare institutions that took the form of Schools of Industries in the apartheid period. The thesis asserts that the motivation for the development of the institution under apartheid was not just the extension of crude apartheid policy, but was also inspired by welfarist and humanitarian goals. -

Serious Crime in Khayelitsha and Surrounding Areas

SERIOUS CRIME IN KHAYELITSHA AND SURROUNDING AREAS CRIME RESEARCH AND STATISTICS CRIME INTELLIGENCE Compiled by M EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This assessment of Khayelitsha and its surrounding areas is based purely on the recorded incidence of crime and was done without any recent contact with and/or visit to any of the stations under consideration (the current situation with regard to the position of the CIO/CIAC at stations is explained in the introduction). Although this methodology possibly promoted increased objectivity in the crime assessment, it may suffer from a lack of insight regarding the crime situation at ground level in Khayelitsha, Mitchells Plain, Harare, Lingelethu West and Mfuleni and thus not present a full explanation. It should again be emphasized that it is an assessment of crime and not of policing in Khayelitsha. The reader should be aware of the fact that Khayelitsha and Mitchells Plain were declared presidential stations in the Western Cape during the late nineties of the previous centuryi. The strategy behind declaring 14 police stations in the Republic of South Africa as presidential stations was that these stations were generally identified as the largest single generators of crime in their respective provinces. The high levels of particularly violent crime in these precincts were also due to an extremely complex web of historical, social, economic and environmental issues which couid only be addressed by a massive, fully integrated effort involving both Government (not only the SAPS) and the community, if the present Khayelitsha precinct as in (2012) and part of its environment (Harare and Lingelethu West) which formerly formed part of the historical Khayelitsha precinct of 1999 are compared to the situation that existed in 1999, the question needs to be asked and answers found regarding the nature and extent of changes over the past 13 years - and whether a massive, fully — integrated government-community effort did in fact materialized in the areas. -

The Making and Re-Imagining of Khayelitsha

The Making and Re-imagining of Khayelitsha Josette Cole Executive Director, Development Action Group (DAG) and Research Associate, Centre for Archive and Public Culture, University of Cape Town Report for the Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of Police Inefficiency in Khayelitsha and a Breakdown in Relations between the Community and the Police in Khayelitsha January 2013 PREFACE During a working career that now spans 37 years I have worked in a number of institutions – i.e. VERITAS, the Surplus People’s Project, W. Cape (SPP), the MANDLOVU Development Initiative and, the Development Action Group (DAG). In all of these I have both honed and applied incremental skills learnt from direct practice to design and implement programmes and projects related to urban land, housing, local government, community development and, capacity building in the context of a pro-poor agenda. Between 1996 and 2012 I also worked as a freelance development consultant and researcher through my small company, Social Trends Development Services, where I worked on numerous assignments for government, the NGO sector, and international NGOs related to the design and evaluation of a range of programmes and projects linked to reconstruction and development in the context of our democratic transition. In between my professional work I have researched, written and published numerous articles, academic papers and books, three of the latter extensively cover various aspects of Cape Town’s social history, with a special focus on past and present settlement life in the South-east Metro of the city. I am a Research Associate in the Archive and Public Culture Research Initiative based in the Social Anthropology Department at the University of Cape Town (UCT) and about to formally register as a PhD candidate in Historical Studies at UCT. -

Endulini Brochure

R 9 650* p/m FROM YOU OWN A VIEW LIKE THIS! YOUR HOME ON THE HILL FROM R 9 650* p/m YOU OWN A VIEW LIKE THIS! YOUR HOME ON THE HILL BRACKENFELL, CAPE TOWN LUXURY 2 BEDROOM 2 BATHROOM | APARTMENTS | No Transfer Duty | No Attorney Transfer Fees | No Bond Registration Fees YOUR HOME ON THE HILL BRACKENFELL, CAPE TOWN LUXURY 2 BEDROOM 1 BATHROOM R 1 349 900 | APARTMENTS | FROM No Transfer Duty | No Attorney Transfer Fees | No Bond Registration Fees unique to ENDULINI The site of the development is beautifully located on the crest of a hill, with most units being afforded incredible views of Table Mountain or the Winelands. Most units have magnificent views Endulini will be a security complex comprising 61 sectional title apartments. These homes are all 2-bedroom properties with a choice of 1 or 2 bathrooms. All units will have a patio or balcony with a built-in-braai. Multiple apartment layouts to choose from Brackenfell, the suburb within which this development falls, is an established area undergoing rapid expansion 2 Bathrooms in many units on its outskirts to cater for the huge demand of the middle-income community. The demand for 2-bedroom units in established, safe areas such as this is very high, catering to a broad market of owner-occupiers, Choose your own finishes (mood investors and rentees. The complex will be access controlled with one entrance gate surrounded by walls choice) with electric fencing. Large unit sizes 73 - 83sqm The units will be more spacious than most 2 bedroom units in the area at 73 - 83sqm in size.