The Rise of Psychological Fundamentalism in Public Health and Welfare Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Birmingham Austerity and Anti-Austerity

University of Birmingham Austerity and anti-austerity Bailey, David; Shibata, Saori DOI: 10.1017/S0007123416000624 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Bailey, D & Shibata, S 2017, 'Austerity and anti-austerity: the political economy of refusal in ‘low resistance’ models of capitalism', British Journal of Political Science, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 683-709. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123416000624 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Eligibility for repository: Checked on 6/12/2016 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Inflicting the Structural Violence of the Market: Workfare and Underemployment to Discipline the Reserve Army of Labor

Fast Capitalism ISSN 1930-014X Volume 12 • Issue 1 • 2015 doi:10.32855/fcapital.201501.011 Inflicting the Structural Violence of the Market: Workfare and Underemployment to Discipline the Reserve Army of Labor Christian Garland “Taking them as a whole, the general movements of wages are exclusively regulated by the expansion and contraction of the industrial reserve army, and these again correspond to the periodic changes of the industrial cycle. They are, therefore, not determined by the variations of the absolute number of the working population, but by the varying proportions in which the working-class is divided into active and reserve army, by the increase or diminution in the relative amount of the surplus-population, by the extent to which it is now absorbed, now set free.”[2] — Marx, K. (1867) Inflicting the Structural Violence of the Market As the ongoing crisis of capitalism continues beyond its sixth year, the effects have been felt with different degrees of severity in different countries. In the UK it has manifested in chronic levels of underemployment which veil the already very high unemployment total that is currently hovering not far off the early 1980s levels of around three million. This data takes into consideration the official unemployment total and combines it with the number of Job Seekers Allowance (JSA) claimants now ‘self-employed’ who work in various odd jobs such as catalogue selling or holding an eBay account now claim Tax Credits to supplement their meager earnings. As such, “record falls in unemployment” and “record numbers in employment” are really not what they seem. -

Conditionality, Activation and the Role of Psychology in UK Government Workfare Programmes Lynne Friedli,1 Robert Stearn2

View metadata, citation and similar papersDownloaded at core.ac.uk from http://mh.bmj.com/ on June 16, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com brought to you by CORE provided by Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Critical medical humanities Positive affect as coercive strategy: conditionality, activation and the role of psychology in UK government workfare programmes Lynne Friedli,1 Robert Stearn2 1London, UK ABSTRACT This paper considers the role of psychology in formu- 2 Department of English and Eligibility for social security benefits in many advanced lating, gaining consent for and delivering neoliberal Humanities, School of Arts, Birkbeck, University of London, economies is dependent on unemployed and welfare reform, and the ethical and political issues London, UK underemployed people carrying out an expanding range this raises. It focuses on the coercive uses of psych- of job search, training and work preparation activities, ology in UK government workfare programmes: as Correspondence to as well as mandatory unpaid labour (workfare). an explanation for unemployment (people are Dr Lynne Friedli, 22 Mayton Increasingly, these activities include interventions unemployed because they have the wrong attitude or Street, London N7 6QR, UK; [email protected] intended to modify attitudes, beliefs and personality, outlook) and as a means to achieve employability or notably through the imposition of positive affect. Labour ‘job readiness’ (possessing work-appropriate attitudes Accepted 9 February 2015 on the self in order to achieve characteristics said to and beliefs). The discourse of psychological deficit increase employability is now widely promoted. This has become an established feature of the UK policy work and the discourse on it are central to the literature on unemployment and social security and experience of many claimants and contribute to the view informs the growth of ‘psychological conditional- that unemployment is evidence of both personal failure ity’—the requirement to demonstrate certain atti- and psychological deficit. -

A Micro-Econometric Evaluation of the UK Work Programme

'I, Daniel Blake' revisited: A micro-econometric evaluation of the UK Work Programme Danula K. Gamage∗ Pedro S. Martinsy Queen Mary University of London Queen Mary University of London CRED & NovaSBE & IZA June 19, 2017 Work in Progress Abstract Although many countries are making greater use of public-private partnerships in em- ployment services, there are few detailed econometric analysis of their effects, in contrast to a large body of small-sample or qualitative case studies. This paper contributes to this literature by examining the case of the UK Work Programme, drawing on popula- tion data of all nearly two-million participants between 2011 and 2016. We also exploit the original structure of the programme to disentangle the impact of different provider and jobseeker characteristics from business cycle, cohort, regional and time-in-programme effects. Moreover, we consider both transitions to employment and transitions out of unemployment. Our main results indicate considerable differences in performance across providers and across jobseeker profiles. The latter results suggest that, by changing the incentive structure offered to providers, the government could obtain better results at the same cost. Keywords: Public employment services, job search, public policy evaluation. JEL Codes: J64, J68, J22. ∗Corresponding author. Email: [email protected], Address: School of Business and Management, Queen Mary, University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS, United Kingdom. yEmail: [email protected]. Address: School of Business and Management, Queen Mary, University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS, United Kingdom. Web: http://webspace.qmul.ac.uk/pmartins 1 1 Introduction Focusing on the individual case of a fictional elderly widower, the award-winning film 'I, Daniel Blake' portraits a negative facade of UK welfare-to-work programmes over the last years. -

Work Programme Supply Chains

Work Programme Supply Chains The information contained in the table below reflects updates and changes to the Work Programme supply chains and is correct as at 30 September 2013. It is published in the interests of transparency. It is limited to those in supply chains delivering to prime providers as part of their tier 1 and 2 chains. Definitions of what these tiers incorporate vary from prime provider to prime provider. There are additional suppliers beyond these tiers who are largely to be called on to deliver one off, unique interventions in response to a particular participants needs and circumstances. The Department for Work and Pensions fully anticipate that supply chains will be dynamic, with scope to flex and evolve to reflect change within the labour market and participant needs. The Department intends to update this information at regular intervals (generally every 6 months) dependant on time and resources available. In addition to the Merlin standard, a robust process is in place for the Department to approve any supply chain changes and to ensure that the service on offer is not compromised or reduced. Comparison between the corrected March 2013 stock take and the September 2013 figures shows a net increase in the overall number of organisations in the supply chains across all sectors. The table below illustrates these changes Sector Number of organisations in the supply chain Private At 30 September 2013 - 367 compared to 351 at 31 March 2013 Public At 30 September 2013 - 128 compared to 124 at 30 March 2013 Voluntary or Community (VCS) At 30 September 2013 - 363 compared to 355 at 30 March 2013 Totals At 30 September 2013 - 858 organisations compared to 830 at March 2013. -

Motion: a Call to Boycott Workfare Schemes

Motion: A call to boycott workfare schemes This Union Branch notes: 1. That there are currently several schemes which place benefits claimants on compulsory unpaid work placements. These include: • “Mandatory Work Activity” • “Sector Based Work Academies” and “Community Action Programme” • As part of what is mandated by the private companies who run the “Work Programme” • The DWP “Work Experience”, which is enforced with the threat of MWA if people do not participate. 2. Each of these schemes mandates a jobseeker to work without pay on threat of loss of benefits (“sanction”). Since October 2012, the government can stop benefits for up to three years. 3. The reform is being rolled out at a time when education and training schemes, housing benefit and other public services are being cut. Unpaid work inevitably replaces paid jobs and pushes wages down. 4. Under workfare, ‘volunteering’ loses its voluntary aspect and become compulsion, watched over by charities and companies. Placement providers are expected to monitor the attendance of people on workfare, report on their behaviour, and provide other information to the DWP that can result in severe penalties for recipients. 5. Compulsory unpaid work placements are being offered to the voluntary, public and private sectors. If unions and workplaces refuse to participate, this makes the programme much less viable. The Union Branch believes: 1. That everyone is entitled to decent work, training and income. Benefits are also a right, not a privilege and need to be protected. 2. That we need to act in solidarity with the most vulnerable in society to protect benefits as part of defending society against a wider attack on the welfare state as a whole. -

Document Title

Work Programme Contents At a Glance – Work Programme Introduction Change of circumstances Mandatory referrals Optional referrals / mandatory participation Voluntary referrals / voluntary participation Claimant working for 26 weeks or more and treated as an early completer Work Programme completers Light Touch regime At a Glance – Work Programme The Work Programme gives up to two years of extra support to claimants who need more help in finding and staying in work. The Work Programme provider decides how best to support claimants referred to them, through a ‘black box' approach. The last date for referrals to the Work Programme was 31st March 2017. All claimants referred on or before this date will remain on the Work Programme for up to 104 weeks even if they move into work, unless they complete the Work Programme early. Claimants were referred to the Work Programme at different points in their Universal Credit claim. A referral could either be mandatory or voluntary. Some voluntary referrals resulted in the claimant having to participate on a mandatory basis. A change in a claimant’s circumstances can result in changes to the nature of participation on the Work Programme and to their agreed commitments. Additional support is provided to claimants in the Intensive Work Search regime when they complete the Work Programme. Introduction The Work Programme provides up to two years of extra support to claimants who need more help in finding and staying in work. The Work Programme providers decide how best to support claimants referred to them, through a ‘black box' approach. The claimant’s Commitment provided the foundation for referral to the Work Programme and claimants were issued with a new Commitment as part of the referral process. -

DWP's Commercial Agreement for Employment and Health

DWP’s Commercial Agreement for Employment and Health Related Services (Release 5 October 2020) ERSA is pleased to be able to inform you of the organisations on Tier 1 and Tier 2 of the DWP Commercial Agreement for Employment and Health Related Services (CAEHRS). In total the DWP received submissions from 61 organisations with a total of 171 compliant submissions across the 7 regional lots. Overall, this has resulted in a total of 28 organisations being awarded a place on CAEHRS, 21 of which have multiple places and 7 have single awards. As set out during this competition the design of CAEHRS allows the department to offer further places they become available. The department does not currently have any plans to undertake further activity at this time but will formally notify the market as appropriate. Those that have been unsuccessful on this occasion are able to bid for future opportunities on CAEHRS. As communicated previously CAEHRS is already planned to be used for Scotland JETS delivery in Regional Lot 7 later this month and the Long-term unemployment programme that subject to further decisions will be outlined shortly. ERSA’s Chief Executive, Elizabeth Taylor said “This announcement is welcomed by the sector. ERSA is scheduling a series of events to provide more information about the successful organisations and the DWP’s plans, these events will keep the sector informed, build partnerships, and enable collaboration”. ERSA is running a series of Meet the Primes events, the first of which will be on Friday 23 October at 1pm. This will be followed by ERSA Member Forums based on the 7 CPA/ regional lot areas. -

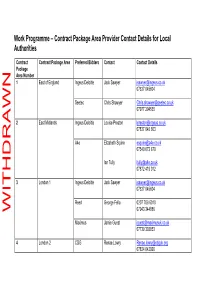

Work Programme – Contract Package Area Provider Contact Details for Local Authorities

Work Programme – Contract Package Area Provider Contact Details for Local Authorities Contract Contract Package Area Preferred Bidders Contact Contact Details Package Area Number 1 East of England Ingeus Deloitte Jack Sawyer [email protected] 07837 045604 Seetec Chris Shawyer [email protected] 07977 294535 2 East Midlands Ingeus Deloitte Louise Preston [email protected] 07837 045 603 A4e Elizabeth Squire [email protected] 07540 673 670 Ian Tully [email protected] 07872 419 012 3 London 1 Ingeus Deloitte Jack Sawyer [email protected] 07837 045604 Reed George Fella 0207 708 6010 07943 344886 WITHDRAWN Maximus Jamie Guest [email protected] 07739 302853 4 London 2 CDG Renae Lowry [email protected] 07824 642926 Seetec Andrew Emerson [email protected] 07977 002278 A4e Jenny Smith [email protected] 07540 673678 Mark Roberts [email protected] 07545 423 778 5 North East Ingeus Deloitte Neil Johnson [email protected] 07557 281648 Avanta Kaye Rideout [email protected] (Regional Director) 07590 418294 6 North West 1 Ingeus Deloitte Barry Fletcher [email protected] 07800 624722 A4e Rhys Harris [email protected] 07872 424 457 Di Ainsworth [email protected] 07880 786707 7 North West 2 G4S George Selmer [email protected] 0161 618 1792 WITHDRAWN Avanta Marie Murray– [email protected] Henderson (Regional 07872 502912 Director) Amanda Stewart [email protected] (Regional Director) 07971 248945 Seetec Debra Fullerton [email protected] 0161 236 8964 8 -

An Interdisciplinary Journal

FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISMFast Capitalism FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM ISSNFAST XXX-XXXX CAPITALISM FAST Volume 1 • Issue 1 • 2005 CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITA LISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM FAST CAPITALISM -

Coalition Government Extends “Slave Labour” Welfare Policy

Analysis Discipline and discontent: coalition government extends “slave labour” welfare policy Chris Jones Under the government’s Work Programme, unemployed people must work for free for private companies such as Tesco and Primark or face losing their benefit payments. These companies manage the programme “without prescription from government” and are given access to sensitive personal data. The government is determined to bolster the number of people involved in the scheme. Disabled people have been increasingly targeted for enrolment and the government’s Universal Credit welfare plan will see thousands of individuals become eligible for referral. Since the late 1990s, successive governments in the UK have introduced “work-for-your-benefit” policies through which the receipt of unemployment benefits is conditional upon the undertaking of certain activities – for example, filling in a minimum number of job applications every week. Following its formation in May 2010, the coalition government introduced the Work Programme which raised the number and intensity of activities required of those claiming benefits. It also increased the severity of sanctions that can be imposed should people not comply. The activities – which in many cases include unwaged work – are prescribed by private firms with government contracts. These firms exercise considerable power over the individuals involved. Upon referral to the Work Programme by a member of staff at a Jobcentre Plus, a letter is sent to the claimant. It states that the provider or one of their partners: “Will support you whilst on the Work Programme. They will discuss what help you need to find work, and draw up an action plan of things you’ll do to improve your chances of getting and keeping a job. -

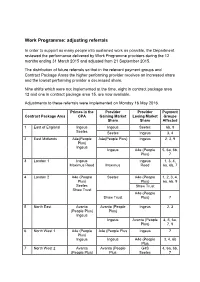

Work Programme: Adjusting Referrals

Work Programme: adjusting referrals In order to support as many people into sustained work as possible, the Department reviewed the performance delivered by Work Programme providers during the 12 months ending 31 March 2015 and adjusted from 21 September 2015. The distribution of future referrals so that in the relevant payment groups and Contract Package Areas the higher performing provider receives an increased share and the lowest performing provider a decreased share. Nine shifts which were not implemented at the time, eight in contract package area 12 and one in contract package area 15, are now available. Adjustments to these referrals were implemented on Monday 16 May 2016. Primes in the Provider Provider Payment Contract Package Area CPA Gaining Market Losing Market Groups Share Share Affected 1 East of England Ingeus Ingeus Seetec 6b, 9 Seetec Seetec Ingeus 3, 4 2 East Midlands A4e(People A4e(People Plus) Ingeus 2, 3, 9 Plus) Ingeus Ingeus A4e (People 5, 6a, 6b, Plus) 7 3 London 1 Ingeus Ingeus 1, 3, 4, Maximus Reed Maximus Reed 6a, 6b, 7 4 London 2 A4e (People Seetec A4e (People 1, 2, 3, 4, Plus) Plus) 6a, 6b, 9 Seetec Shaw Trust Shaw Trust A4e (People Shaw Trust Plus) 7 5 North East Avanta Avanta (People Ingeus 2, 3 (People Plus) Plus) Ingeus Ingeus Avanta (People 4, 5, 6a, Plus) 7, 9 6 North West 1 A4e (People A4e (People Plus Ingeus 7 Plus) Ingeus Ingeus A4e (People 3, 4, 6b Plus 7 North West 2 Avanta Avanta (People G4S 4, 6a, 6b, (People Plus) Plus Seetec 7 G4S G4S Avanta (People 1 Seetec Plus) Seetec Avanta (People 9 Plus)