An Interdisciplinary Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Birmingham Austerity and Anti-Austerity

University of Birmingham Austerity and anti-austerity Bailey, David; Shibata, Saori DOI: 10.1017/S0007123416000624 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Bailey, D & Shibata, S 2017, 'Austerity and anti-austerity: the political economy of refusal in ‘low resistance’ models of capitalism', British Journal of Political Science, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 683-709. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123416000624 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Eligibility for repository: Checked on 6/12/2016 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Eighteenth Report Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill

Law Commission Reforming the law Statute Law Repeals: Eighteenth Report Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill Joint Report Law Com No 308 / Scot Law Com No 210 The Law Commission and The Scottish Law Commission (LAW COM No 308) (SCOT LAW COM No 210) STATUTE LAW REPEALS: EIGHTEENTH REPORT DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL Presented to the Parliament of the United Kingdom by the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice by Command of Her Majesty Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers January 2008 Cm 7303 SG/2008/4 £25.75 The Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission were set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Etherton, Chairman Mr Stuart Bridge Mr David Hertzell Professor Jeremy Horder Mr Kenneth Parker QC The interim Chief Executive of the Law Commission is Mr William Arnold.1 The Law Commission is located at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WC1N 2BQ. The Scottish Law Commissioners are: The Honourable Lord Drummond Young, Chairman Professor George L Gretton Professor Gerard Maher QC Professor Joseph M Thomson Mr Colin J Tyre QC The Chief Executive of the Scottish Law Commission is Mr Michael Lugton. The Scottish Law Commission is located at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh, EH9 1PR. The terms of this report were agreed on 3 December 2007 The text of this report is available on the Internet at: http://www.lawcom.gov.uk http://www.scotlawcom.gov.uk 0 Crown Copyright 2008 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. -

A Thesis Entitled Yoshimoto Taka'aki, Communal Illusion, and The

A Thesis entitled Yoshimoto Taka’aki, Communal Illusion, and the Japanese New Left by Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for requirements for The Master of Arts Degree in History ________________________ Adviser: Dr. William D. Hoover ________________________ Adviser: Dr. Peter Linebaugh ________________________ Dr. Alfred Cave ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo (July 2005) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is customary in a note of acknowledgments to make the usual mea culpa concerning the impossibility of enumerating all the people to whom the author has incurred a debt in writing his or her work, but, in my case, this is far truer than I can ever say. This note is, therefore, a necessarily abbreviated one and I ask for a small jubilee, cancellation of all debts, from those that I fail to mention here due to lack of space and invidiously ungrateful forgetfulness. Prof. Peter Linebaugh, sage of the trans-Atlantic commons, who, as peerless mentor and comrade, kept me on the straight and narrow with infinite "grandmotherly kindness" when my temptation was always to break the keisaku and wander off into apostate digressions; conversations with him never failed to recharge the fiery voltage of necessity and desire of historical imagination in my thinking. The generously patient and supportive free rein that Prof. William D. Hoover, the co-chair of my thesis committee, gave me in exploring subjects and interests of my liking at my own preferred pace were nothing short of an ideal that all academic apprentices would find exceedingly enviable; his meticulous comments have time and again mercifully saved me from committing a number of elementary factual and stylistic errors. -

Statute Law Revision Bill 2007 ————————

———————— AN BILLE UM ATHCHO´ IRIU´ AN DLI´ REACHTU´ IL 2007 STATUTE LAW REVISION BILL 2007 ———————— Mar a tionscnaı´odh As initiated ———————— ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Definitions. 2. General statute law revision repeal and saver. 3. Specific repeals. 4. Assignment of short titles. 5. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1896. 6. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1962. 7. Miscellaneous amendments to post-1800 short titles. 8. Evidence of certain early statutes, etc. 9. Savings. 10. Short title and collective citation. SCHEDULE 1 Statutes retained PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 [No. 5 of 2007] SCHEDULE 2 Statutes Specifically Repealed PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 ———————— 2 Acts Referred to Bill of Rights 1688 1 Will. & Mary, Sess. 2. c. 2 Documentary Evidence Act 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. 37 Documentary Evidence Act 1882 45 & 46 Vict., c. 9 Dower Act, 1297 25 Edw. 1, Magna Carta, c. 7 Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) (No. 2) 1867 31 & 32 Vict., c. 3 Dublin Hospitals Regulation Act 1856 19 & 20 Vict., c. 110 Evidence Act 1845 8 & 9 Vict., c. 113 Forfeiture Act 1639 15 Chas., 1. c. 3 General Pier and Harbour Act 1861 Amendment Act 1862 25 & 26 Vict., c. -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

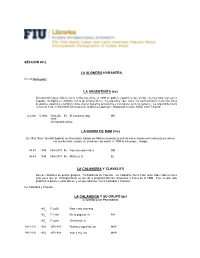

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

Inflicting the Structural Violence of the Market: Workfare and Underemployment to Discipline the Reserve Army of Labor

Fast Capitalism ISSN 1930-014X Volume 12 • Issue 1 • 2015 doi:10.32855/fcapital.201501.011 Inflicting the Structural Violence of the Market: Workfare and Underemployment to Discipline the Reserve Army of Labor Christian Garland “Taking them as a whole, the general movements of wages are exclusively regulated by the expansion and contraction of the industrial reserve army, and these again correspond to the periodic changes of the industrial cycle. They are, therefore, not determined by the variations of the absolute number of the working population, but by the varying proportions in which the working-class is divided into active and reserve army, by the increase or diminution in the relative amount of the surplus-population, by the extent to which it is now absorbed, now set free.”[2] — Marx, K. (1867) Inflicting the Structural Violence of the Market As the ongoing crisis of capitalism continues beyond its sixth year, the effects have been felt with different degrees of severity in different countries. In the UK it has manifested in chronic levels of underemployment which veil the already very high unemployment total that is currently hovering not far off the early 1980s levels of around three million. This data takes into consideration the official unemployment total and combines it with the number of Job Seekers Allowance (JSA) claimants now ‘self-employed’ who work in various odd jobs such as catalogue selling or holding an eBay account now claim Tax Credits to supplement their meager earnings. As such, “record falls in unemployment” and “record numbers in employment” are really not what they seem. -

Behind the Contract for Welfare Reform: Antecedent Themes in Welfare to Work Programs

Behind the contract for welfare reform: antecedent themes in welfare to work programs Article (Published Version) Paz-Fuchs, Amir (2008) Behind the contract for welfare reform: antecedent themes in welfare to work programs. Berkeley Journal of Labor and Employment Law, 29 (2). pp. 101-150. ISSN 1067-7666 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/46104/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Behind the Contract for Welfare Reform: Antecedent Themes in Welfare to Work Programs Amir Paz-Fuchs† “What’s past is prologue.” —The Tempest Welfare-to-work programs throughout history and across jurisdictions exhibit similar traits, in form as well as in substance. -

Conditionality, Activation and the Role of Psychology in UK Government Workfare Programmes Lynne Friedli,1 Robert Stearn2

View metadata, citation and similar papersDownloaded at core.ac.uk from http://mh.bmj.com/ on June 16, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com brought to you by CORE provided by Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Critical medical humanities Positive affect as coercive strategy: conditionality, activation and the role of psychology in UK government workfare programmes Lynne Friedli,1 Robert Stearn2 1London, UK ABSTRACT This paper considers the role of psychology in formu- 2 Department of English and Eligibility for social security benefits in many advanced lating, gaining consent for and delivering neoliberal Humanities, School of Arts, Birkbeck, University of London, economies is dependent on unemployed and welfare reform, and the ethical and political issues London, UK underemployed people carrying out an expanding range this raises. It focuses on the coercive uses of psych- of job search, training and work preparation activities, ology in UK government workfare programmes: as Correspondence to as well as mandatory unpaid labour (workfare). an explanation for unemployment (people are Dr Lynne Friedli, 22 Mayton Increasingly, these activities include interventions unemployed because they have the wrong attitude or Street, London N7 6QR, UK; [email protected] intended to modify attitudes, beliefs and personality, outlook) and as a means to achieve employability or notably through the imposition of positive affect. Labour ‘job readiness’ (possessing work-appropriate attitudes Accepted 9 February 2015 on the self in order to achieve characteristics said to and beliefs). The discourse of psychological deficit increase employability is now widely promoted. This has become an established feature of the UK policy work and the discourse on it are central to the literature on unemployment and social security and experience of many claimants and contribute to the view informs the growth of ‘psychological conditional- that unemployment is evidence of both personal failure ity’—the requirement to demonstrate certain atti- and psychological deficit. -

Perro Muerto En Tintoterería: Los Fuertes

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Teatro: Textos/Creación 2007 Perro muerto en tintoterería: Los fuertes Angélica Liddell Jesús Eguía Armenteros Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/teatro_obrascreativas This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Teatro: Textos/Creación by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Este libro ha sido publicadopor la Cátedra Valle-Inclán/Lauro Olmo del Ateneo de Madrid y el Aula de Estudios Escénicos y Medios Audiovisuales de la Universidadde Alcalá con la colaboración de su servicio de Publicaciones y con la financiaciónde la Fundación Caja Madrid © Ateneo de Madrid Cátedra Valle-lnclán / Lauro Olmo Del texto: Angélica Liddell De la Introducción: Jesús Eguía Annenteros Diseño de cubierta: Soledad Sánchez ISSN: 1132-2233 Depósito Legal: M-21891-1993 Imprime: Nuevo Siglo, S.L. PRÓLOGO 7 ANGÉLICALIDDELL PERRO MUERTO EN TINTORERÍA: LOS FUERTES ATENEO DE MADRID CÁTEDRA VALLE-INClÁNILAURO OLMO LA REPÚBLICA FRENTE A LA HUMANIDAD Angélica Liddell (Figueres, 1966) ha desarrollado una vasta carrera en todos los campos del arte dramático. En dieciocho años de trayectoria, ha escrito 32 piezas escénicas, además de poesía, relatos y artículos. Como autora ha recibido los premios Ciudad de Alcorcón de Teatro (1989), el Premio X Certamen de Relatos «Imágenes de Mujen> del Ayuntamiento de León (1999), el Pre mio de Dramaturgia Innovadora de la Casa de América (2003), el Premio SGAE de Teatro (2004) y el Ojo Crítico Segundo Milenio (2005) a toda su trayectoria. -

Universidad Peruana De Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC)

La influencia musical del reguetón en el género musical urbano actual en Hispanoamérica (2000 – 2019) Item Type info:eu-repo/semantics/bachelorThesis Authors Alban Celis, Enrique Esteban Publisher Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC) Rights info:eu-repo/semantics/openAccess; Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Download date 26/09/2021 00:11:21 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10757/650327 UNIVERSIDAD PERUANA DE CIENCIAS APLICADAS FACULTAD DE ARTES CONTEMPORÁNEAS PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO DE MÚSICA La influencia musical del reguetón en el género musical urbano actual en Hispanoamérica (2000 – 2019) TRABAJO DE INVESTIGACIÓN Para optar el grado de bachiller en Música con Especialidad en Producción AUTOR(ES) Alban Celis, Enrique Esteban (0000-0002-9626-6684) ASESOR(ES) Bacacorzo Diaz, Jorge Francisco Martin (0000-0002-8019-3687) Lima, 7 de diciembre de 2019 DEDICATORIA A mi familia, principalmente, por permitirme estudiar la carrera que siempre soñé y apoyarme en todas mis decisiones. A mis padres, por impulsarme cual flecha y apuntar lejos con la educación que siempre me brindaron. 1 RESUMEN Durante muchos años el reguetón ha sido objeto de críticas por parte de la comunidad de músicos académicos y público cuya preferencia musical radica en otros géneros musicales. Esto deriva en el desprecio del reguetón y la negación de su aporte musical a la industria musical que hoy en día se percibe. Sin embargo, es importante reconocer la trascendencia del género y su influencia en el hoy nombrado género urbano; lo cual, se evidencia a través del exhaustivo análisis musical en los temas más famosos de artistas reconocidos a nivel internacional como Daddy Yankee, Enrique Iglesias, Don Omar, entre otros. -

Cancionero Coro De Jóvenes – Letras

CORO DE JÓVENES SAN JUAN EVANGELISTA CANCIONERO DE LETRAS 1 A ÉL SEA LA GLORIA Todo es de mi Cristo, Por Él y para Él. Todo es de mi Cristo, Por Él y para Él. A Él sea la gloria, A Él sea la gloria, A Él sea la gloria, por siempre Amén. A TI ME RINDO Ante ti postrado estoy aquí Te rindo mi ser, te rindo mi ser Con tu Amor atráeme Señor Vengo a tus pies, vengo a tus pies A TI ME RINDO, A TI ME RINDO Lléname, de gracia inúndame Sacia mi sed, sacia mi sed Mi corazón levanta un clamor Háblame Dios, háblame Dios A TI ME RINDO, A TI ME RINDO TE QUIERO CONOCER MÁS DE TI CONOCER CON TU ALIENTO DIOS SOPLA EN MI INTERIOR CUMPLE SEÑOR TU VOLUNTAD EN MÍ CON TU GRAN PODER MUÉVETE EN MI SER CUMPLE SEÑOR TU VOLUNTAD EN MÍ ABBA, PADRE Ante ti venimos pues Tú nos has llamado, y nos atrae tu voz Como un solo pueblo danzando en Tú presencia, te damos el honor. Sobre nosotros descienda el poder de Tú Espíritu que nos hará clamar: ABBA, PADRE; ABBA, PADRE HOY TUS HIJOS CANTAMOS, TU AMOR CELEBRAMOS CLAMANDO CON UNA VOZ (2) ABBA, PADRE; ABBA, PADRE; ABBA, PADRE. ACLAMACIÓN (Corona de adviento) VEN SEÑOR, LÍBRANOS, VEN TU PUEBLO A REDIMIR, LA ESPERANZA BRILLARÁ, VEN SEÑOR JESÚS. 2 ACLAMAD AL SEÑOR Aclamad al Señor la tierra entera, y servid al Señor con alegría, venid gozosos en su nombre y sabed que el Señor es nuestro Dios. -

Analyzing the Communist Manifesto

Analyzing the Communist Manifesto The Adventures of the Communist Manifesto Hal Draper Haymarket Books, 2020, xiv + 352 pp. One hundred and seventy-two years after its original publication, the Communist Manifesto never seems to go out of style for very long. As the late Marshall Berman once put it, Whenever there’s trouble, anywhere in the world, the book becomes an item; when things quiet down, the book drops out of sight; when there’s trouble again, the people who forgot remember. When fascist-type regimes seize power, it’s always on the list of books to burn. When people dream of resistance—even if they’re not Communists—it provides music for their dreams.1 With the world facing pandemic, economic crisis, growing inequality, political polarization, and rising international tensions, there is certainly no shortage of troubles, so it may have been the right time for Haymarket Books to republish Hal Draper’s The Adventures of the Communist Manifesto, which includes several versions of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ classic text along with detailed commentary by Draper. Draper was an active revolutionary socialist in the United States from the 1930s until his death in 1990. He was a prolific writer (a frequent contributor to New Politics in the 1960s and a member of its editorial board), and his multivolume work, Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution, is still arguably the best study of Marx’s political ideas. Draper was a scholar but never a narrow academic—he wrote for socialist activists who want a deeper understanding of their political tradition precisely so they can respond more effectively to the world’s many troubles.