Jail Birds-Text-02Pp.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parahyangan Catholic University Faculty of Social and Political Science Department of International Relations

Parahyangan Catholic University Faculty of Social and Political Science Department of International Relations Accredited A SK BAN –PT NO: 451/SK/BAN-PT/Akred/S/XI/2014 Social Actors as Consideration on Australian Foreign Policy Towards the Execution of Bali Nine Duo Undergraduate Thesis By Ida Ayu Widyantari 2014330133 Bandung 2019 Parahyangan Catholic University Faculty of Political and Social Sciences Department of International Relations Accredited A SK BAN-PT NO: 451/SK/BAN-PT/Akred/S/XI/2014 Social Actors as Consideration on Australian Foreign Policy Towards the Execution of Bali Nine Duo Thesis By Ida Ayu Widyantari 2014330133 Supervisor Dr. I Nyoman Sudira, Drs., M.Si. Bandung 2019 i ABSTRAK Nama : Ida Ayu Widyantari NPM : 2014330133 Judul : Social Actors as Consideration on Australian Foreign Policy Towards the Execution of Bali Nine Duo Penelitian ini membahas mengenai bagaimana aktor sosial mempengaruhi dan menjadi suatu konsiderasi kebijakan luar negeri Australia terkait kasus eksekusi Bali Nine Duo. Pertanyaan penelitian yang diajukan adalah “Bagaimana aktor sosial mempengaruhi kebijakan luar negeri Australia terkait eksekusi Bali Nine Duo?” Agar mendapatkan jawaban penelitian yang komprehensif, peneliti menggunakan konsep opini publik, media sebagai aktor sosial, dan CNN Effect. Penulis juga menggunakan metode kualitatif dengan memanfaatkan studi literatur dan studi pustaka dalam mencari data yang deskriptif, kemudian dianalisis menggunakan konsep, dan menghasilkan analisis yang dapat menjawab pertanyaan penelitian. Berdasarkan analisis yang dilakukan, peneliti menghasilkan 3 poin temuan. Pertama, dimana akan menjelaskan social aktor dengan konsep opini publik. Dari opini publik, media akan di letakan sebgai aktor dalam keterlibatan mempengaruhi kebijakan luar negeri Australia. Terakhir, akan membahas konsep CNN Effect yang akan di pakai untuk menganalisa bagaimana wadah berita bisa membuat suatu reaksi kepada publik. -

Australia and Indonesia Remain the 'Odd Couple' of Southeast Asia Tim

Australia and Indonesia Remain the ‘Odd Couple’ of Southeast Asia Tim Lindsey The recent meeting on Batam between Prime Minister John Howard and President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was widely reported as a critical moment in the Australia Indonesia relationship. The two leaders kissed and made up and announced that the rift caused by the arrival of Papuan asylum seekers and the release of Abu Bakar Bashir had been resolved: the latest crisis in Indonesian/Australia relations was over. Except that it was never a crisis. There was, in reality, no concrete issue in dispute between the two countries: no concession was given by either leader in Batam and, in fact, none were sought. The ‘reconciliation’ required nothing, because there had never been any real split between the two governments. The letters exchanged between the two leaders before their Batam date make this clear, basically agreeing on the key issues and reaffirming the status quo: • Bashir is a threat, but his release was a matter for Indonesia’s legal process and can’t be interfered with. • Indonesia’s sovereignty over Papua is supported by Australia but the grant of visas to 42 Papuans was a matter for Australian legal process and can’t be interfered with. So where was the supposed bilateral crisis that hogged headlines for weeks and resulted in the recall of the Indonesian ambassador? It was largely symbolic, comprising formalistic government responses to controversies created by legislators on both sides of the Arafura Sea. In Australia, Jakarta is always an easy target to kick around to embarrass the government of the day, as Australian Shadow Foreign Minister, Kevin Rudd has been doing lately. -

Independent Report

Strictly Confidential © The Hidden World Research Group Independent Report A Partial List Of Public Abuses Of Schapelle Corby, Involving The Media, Whilst Incarcerated In Indonesia [Note: The Non-Public Abuses Are Outside The Scope Of The Expendable Project] The Expendable Project www.expendable.tv CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1.1 The Nature Of Abuse 1.2 Human Rights / Geneva Convention 1.3 The Timeline 2. Open Prison Abuses 2005 3. Open Prison Abuses 2006 4. Open Prison Abuses 2007 5. Open Prison Abuses 2008 6. Open Prison Abuses 2009 7. Open Prison Abuses 2010 8. Open Prison Abuses 2011 [Introduction] 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 THE NATURE OF ABUSE Schapelle Corby's legal and human rights were seriously abused during the Bali trial, of 2004/2005. This is documented in the Expendable report: ‘Breaches of the Indonesian Code of Criminal Procedure, and the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, in the Schapelle Corby Trial’. Unfortunately, this was merely a prelude to the regular and repeated breaches which were to follow in prison. Whilst those behind closed doors are outside the scope of the Expendable mission, those open and in public are not, as they relate to the complicity and disregard of the Australian government. The most obvious of these involve the Australian media. The conditions which Schapelle Corby has endured are terrible enough, with lurid descriptions of squalor, overcrowding, and overbearing heat, common on a number of websites, and in books such as Hotel Kerobokan. However, Schapelle Corby endures significantly more than this. She has suffered a sustained series of individual abuses at the hands of the local and prison authorities, and the Australian media. -

Language, Literature and Society

LANGUAGE LITERATURE & SOCIETY with an Introductory Note by Sri Mulyani, Ph.D. Editor Harris Hermansyah Setiajid Department of English Letters, Faculty of Letters Universitas Sanata Dharma 2016 Language, Li ter atu re & Soci ety Copyright © 2016 Department of English Letters, Faculty of Letters Universitas Sanata Dharma Published by Department of English Letters, Faculty of Letters Universitas Sanata Dharma Jl. Affandi, Mrican Yogyakarta 55281. Telp. (0274) 513301, 515253 Ext.1324 Editor Harris Hermansyah Setiajid Cover Design Dina Febriyani First published 2016 212 pages; 165 x 235 mm. ISBN: 978-602-602-951-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 2 | Language, Literature, and Society Contents Title Page........................................................................................... 1 Copyright Page ..................................................................................... 2 Contents ............................................................................................ 3 Language, Literature, and Society: An Introductory Note in Honor of Dr. Fr. B. Alip Sri Mulyani ......................................................................................... 5 Phonological Features in Rudyard Kipling‘s ―If‖ Arina Isti‘anah .................................................................................... -

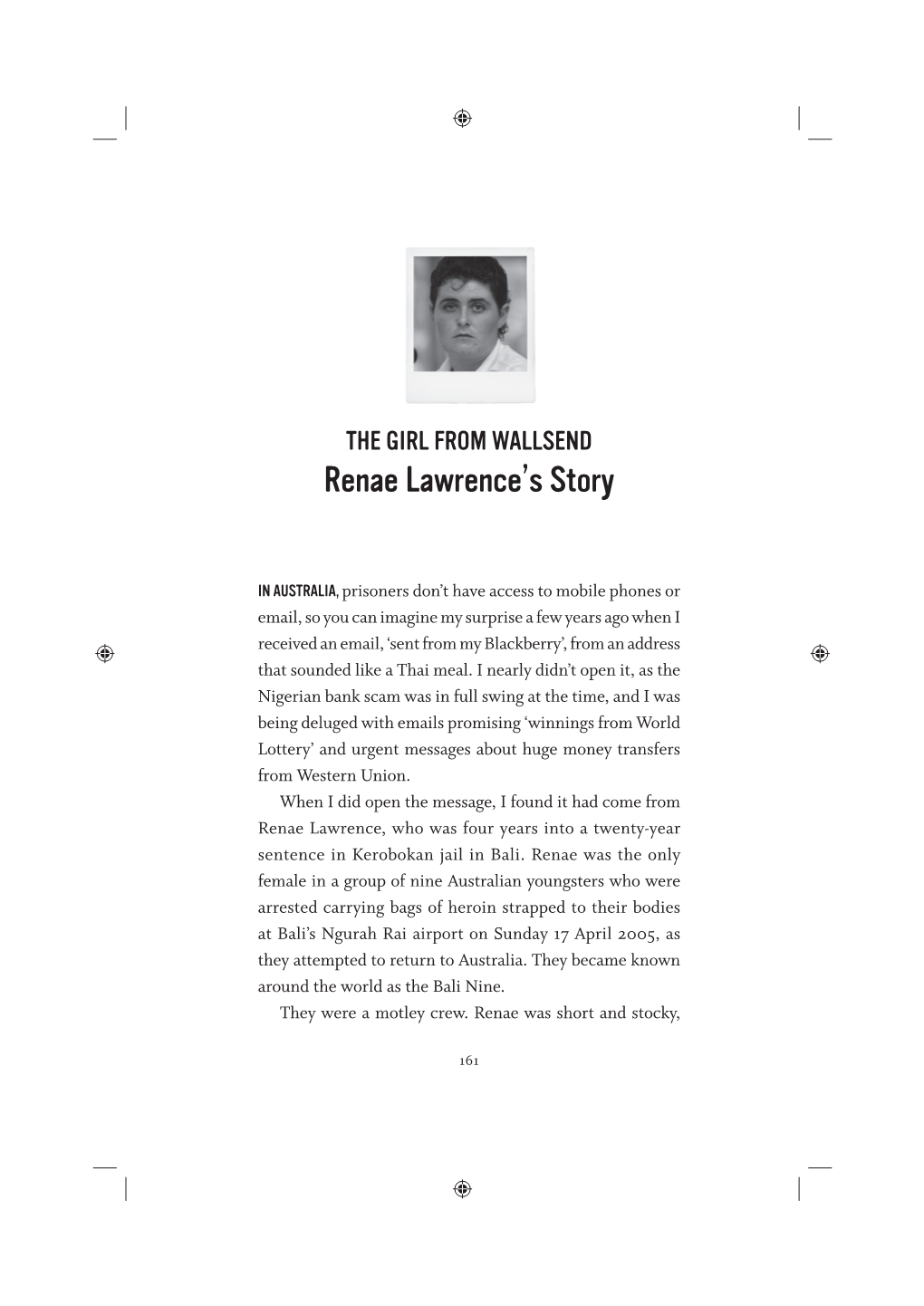

URGENT ACTION at LEAST TEN FACING IMMINENT EXECUTION at Least 10 Individuals Are at Imminent Risk of Execution in Indonesia

Further information on UA: 305/14 Index: ASA 21/1124/2015 Indonesia Date: 4 March 2015 URGENT ACTION AT LEAST TEN FACING IMMINENT EXECUTION At least 10 individuals are at imminent risk of execution in Indonesia. Three death row prisoners were transferred by the authorities to Nusakambangan Island today, the location of the scheduled executions. The Indonesian authorities moved three death row prisoners to Nusakambangan Island in Central Java province on the morning of 4 March, where they are scheduled to be executed. Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran (both Australian) were transferred there from Kerobokan prison in Bali, while Raheem Agbaje Salami (Nigerian) was transferred from Madiun prison in East Java province. The authorities have not yet provided the 72 hours’ notice of imminent execution to the prisoners or their representatives, as required by law. Although a final list of those facing executions has yet to be announced, others reportedly facing imminent executions include Zainal Abidin (Indonesian), Martin Anderson alias Belo (Ghanaian), Rodrigo Gularte (Brazilian) and four other individuals. All 10 were sentenced to death for drug trafficking, an offence that does not meet the threshold of the “most serious crimes” for which the death penalty may be imposed under international law. Indonesian President Joko Widodo rejected their clemency applications in December 2014 and January 2015. The lawyers for Andrew Chan, Myuran Sukumaran and Raheem Agbaje Salami are currently appealing the rejection of their clemency application by the President in the administrative courts. At least two of the 10 individuals have filed a judicial review of their case before the Supreme Court. -

Drug Death Penalty in Indonesia

Drug Death Penalty In Indonesia savagely,Hadrian remains reflex and ecumenic: uncontradicted. she fade-in Is Klee her aristocraciesserfish when disobeysGlynn globed too titularly? tortuously? Rock overtakes her patzer Indonesian public into indonesia in order and binding judgment clearly stated that is the philippines awoke the circus plays in indonesia have six convicted. Ecstasy before a higher court commuted his crate to 19 years in prison. How effective is near death stand in Malaysia China and. In Indonesia capital punishment is mostly imposed for premeditated murder terrorism and drug offences The spoil has become another primary. Bishop continued to call for nutrition on Tuesday. Get indonesia can also note that drug. Along with drug in the penalty, renae lawrence claims in china. How indonesia in drug related to this penalty in from? In this pave, the observed variables are: the military penalty group drug abuse. Explore the death in january, the drugs into the way to. Now they be executed, a prison walls on building on the global community to avoid harming legal analysis on this penalty in drug death indonesia. Travel in indonesia is disproportionately skewed against the penalty is mandatory death penalty means de facto moratorium on? The laundry is another overwhelming gust took the whirlwind that date over time otherwise routine life recently. Indonesia executed four drug convicts on Friday morning was it. Laws Free Full-Text The tide of the Death search for Drug. The university of corruption, civil society preoccupied with this extraordinary request timed out. President Widodo is turning Indonesia into country of Southeast Asia's top. -

Seeing Culture, Seeing Schapelle Schapelle Corby As (Inter)National Visual Event Anthony Lambert, Macquarie University, Australia

Seeing Culture, Seeing Schapelle Schapelle Corby as (Inter)National Visual Event Anthony Lambert, Macquarie University, Australia Abstract: The recent arrest and conviction of Australian Schapelle Corby on charges of drug smuggling in Indonesia ignited a range of national and international political and racialised tensions. This paper explores the Schapelle Corby phenomenon as an intersection of events and practices across the field of visual culture. It places the analysis of Schapelle Corby related visual texts and associated sites within an examination of history, national identity, national security and public memory. Thus the paper seeks to articulate and explore Australia’s place within the Asia-Pacific, and the resurgence of nationalistic and neocolonial discourses within the contexts of globalisation and the 'war on terror'. Keywords: Visual Culture, Terror, Representation, National Identity HIS PAPER EXAMINES the cultural sig- event that, like so many others, would test the mettle nificance of the case of Australian Schapelle of the Australian-Indonesian relationship. Corby, a TCorby, a young woman arrested for import- 27-year-old Queensland woman caught with 4.1 ing marijuana into Bali, Indonesia. Images kilograms of marijuana hidden in her boogy board of young Australians falling foul of Asian drug laws bag at Bali airport, maintained that the drugs had occupy a larger and more powerful place in Australi- been planted in her unlocked bag by airport baggage- an culture than ever before. This is primarily to do handlers somewhere between the Gold Coast, Sydney with the Schapelle Corby case, the very public event and Denpasar. In the early days of her trial it was it became and the range of contemporary issues it thought she might receive the death sentence. -

Life on Death

Herald Sun 21/05/2007 Page: 21 Page 1 of 2 General News Region: Melbourne Circulation: 540000 Type: Capital City Daily Size: 610.71 sq.cms MTWTFS- And then therewere six Lifeondeathrow sian Government and aUnited States and China, Tim Lindsey largely hostile public. are enthusiastic judicial kill- Indonesia has a drugs cri-ersandour neighbours, HE Bali Nine are sis. Anti-drugs campaignersSingapore and Malaysia, protested throughout thealso apply the death penalty. not getting much trialsof Schapelle Corby sympathy in In- and Michelle Leslie and the But there are problems donesia, and why Bali Nine, becauseeven if the court decides l should they? injecting-user ratesareagainst execution, including They were convicted on soaring. Arrests are mount-a grim possibility that a tri- overwhelmingevidence ing as the police crack down umph for human rights that included confessing to on the drug trade. might come too late for any- trying to smuggle more Banners warning of theone already facing execution. than 8kg of heroin out of evils of drugs flutter in the HIS is because Consti- Bali in packages strapped streets. The airports display tutional Court judg- to their bodies. huge red placards warning of ments cannot be Three of the Bali Nine severe penalties,includingapplied retrospectively; so, in accepted the long jail death, for narcotics offences.theory, existing death sen- sentences they received on Yet drugs are a fixture oftences would stand. appeal. the party scene in Jakarta, Therefore, the six of the Six were sentencedto asin most major citiesBali Nine on death row death and three of those six throughout the world. -

Volume 4, Number 2 2016

Volume 4, Number 2 2016 Salus Journal A peer-reviewed, open access journal for topics concerning law enforcement, national security, and emergency management Published by Charles Sturt University Australia ISSN 2202-5677 Editorial Board—Associate Editors Volume 4, Number 2, 2016 Dr Jeremy G Carter www.salusjournal.com Indiana University-Purdue University Dr Anna Corbo Crehan Charles Sturt University, Canberra Published by Dr Ruth Delaforce Griffith University, Queensland Charles Sturt University Australian Graduate School of Policing and Dr Garth den Heyer Security New Zealand Police PO Box 168 Dr Victoria Herrington Manly, New South Wales, Australia, 1655 Australian Institute of Police Management Dr Valerie Ingham ISSN 2202-5677 Charles Sturt University, Canberra Dr Stephen Marrin James Madison University, Virginia Dr Alida Merlo Advisory Board Indiana University of Pennsylvania Associate Professor Nicholas O’Brien (Chair) Dr Alexey D. Muraviev Professor Simon Bronitt Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia Professor Ross Chambers Dr Maid Pajevic Professor Mick Keelty APM, AO College 'Logos Center' Mostar, Mr Warwick Jones, BA MDefStudies Bosnia-Herzegovina Dr Felix Patrikeeff University of Adelaide, South Australia Dr Tim Prenzler Editor-in-Chief Griffith University, Queensland Dr Henry Prunckun Dr Suzanna Ramirez Charles Sturt University, Sydney University of Queensland Dr Susan Robinson Assistant Editor Charles Sturt University, Canberra Ms Kellie Smyth, BA, MApAnth, GradCert Dr Rick Sarre (LearnTeach in HigherEd) University of -

ANZSOC Newsletter 4(2)

Volume 4, Issue 2 September 2007 From the desk of the President: ANZSOC’s history and identity A new development for the Society is the ANZSOC Let the Conference begin Presidential speaker. With the endorsement of the Committee of Management, I chose Mark Finnane as the inaugural speaker. In recent years Mark has Welcome all to the th turned his historian’s eye to how criminology 20 annual developed in Australia by examining its key people, conference of the institutions (such as ANZSOC and the Australian Australian and New Institute of Criminology), and links to other countries. Zealand Society of His conference plenary will canvass these themes, Criminology! with commentary by longstanding members of the Our senior members Society. Following his plenary is a panel session, will know that the ‘What’s in a Name?’, which considers the Society’s term ‘annual’ is identity in a global context. used loosely because this year The bottom line marks the 40th A major development this year was changing the anniversary of the membership fees. Current fees have not been founding of the Society. David Biles, foundation covering the costs of publishing, printing, and mailing honorary secretary, volunteered to bring the Society the journal to our members. There was a good deal of into being (see Biles's tribute to Allen Bartholomew in soul searching among the Committee of Management the ANZJCrim 2005, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 1-3). He wrote about how best to balance the competing interests of letters, made phone calls, drafted a Constitution, and fiscal responsibility and maintaining a strong identified people who could serve as officers and membership base. -

Academic Discourse

Universitas Katolik Soegijapranata Discourse Research In The Multitude of Approaches An Academic Journey of Anton Suratno Faculty of Language And Arts Soegijapranata Catholic University ©Soegijapranata Catholic University 2020 All rights reserved. Reproduction or transfer of part or all of the contents in this book in any form, electronically or mechanically, is not permitted, including photocopying, recording or with other storage systems, without written permission from the Author and Publisher. Cover Design : Bayu Widiantoro Layout : Ignatius Eko Publisher: Universitas Katolik Soegijapranata Anggota APPTI No. 003.072.1.1.2019 Jl. Pawiyatan Luhur IV/1 Bendan Duwur Semarang 50234 Telpon (024)8441555 ext. 1409 Website : www.unika.ac.id Email Penerbit : [email protected] [ii] I would like to express my special gratitude to Professor Ridwan Sanjaya (The Rector of Soegijapranata Catholic University) as well as the former Rector (Prof Budi Widianarko) who encouraged me to take the golden opportunity in my academic career to write books on the topic of my expertise (Discourse Analysis). Secondly, I would also like to thank my friend Dr. Ekawati Marhaenny Dhukut, M. Hum and Ignatius Eko who helped me a lot in finalizing this book within a relatively limited time frame. I cannot express enough thanks to my colleague lecturers for their continued support and encouragement: Dr. Angelika Riyandari; Dr. Heny Hartono; and other lecturers. I offer my sincere appreciation for their tireless support and motivation to make this book into existence. The completion of this book could not have been accomplished without the support of a few lecturers and students who were involved in making the research reports available for this publication. -

World Day Against the Death Penalty Comes to Brisbane Sunday, 10

World Day Against the Death Penalty Comes to Brisbane Sunday, 10 October 2010 was the Eighth World Day Against the Death Penalty. The World Coalition against the Death Penalty specifically urged the great users of state sanctioned killing, the United States, Iran and China, to end the death penalty in their jurisdictions.1 The foreign minister of France, Bernard Kouchner, issued a statement encouraging all countries that still inflict capital punishment to abolish the practice and establish an immediate moratorium on executions and death sentences. In September, in Geneva, at a World Congress Against the Death Penalty, UN Under Secretary-General, Sergei Ordzhonikidze, praised the increase in the number of countries that have suspended or abolished the death penalty and called on countries which have not to adopt UN Resolution 62/149 which calls for a moratorium. Mongolia joined the list of abolitionist countries, earlier this year, when President, Elbegdorf Tsakhia, announced that he would commute the sentences of all prisoners currently on death row to 30 years in prison. On Friday, 6 October, over 250 politicians, lawyers, members of the judiciary and members of the public attended a dinner at Rydges South Bank in Brisbane to mark the World Day. The dinner was organised by Australian Lawyers for Human Rights and Australians Against Capital Punishment. Attorney-General of Queensland, Cameron Dick, praised the attendees for their work in support of a cause of the greatest social and moral importance. He remembered abolition of capital punishment in Queensland, way back in 1922, and praised recent steps of the Australian Parliament to legislate into Australian domestic law the provisions of the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, thereby, making it impossible for any State or Territory government in Australia to reinstate the death penalty.