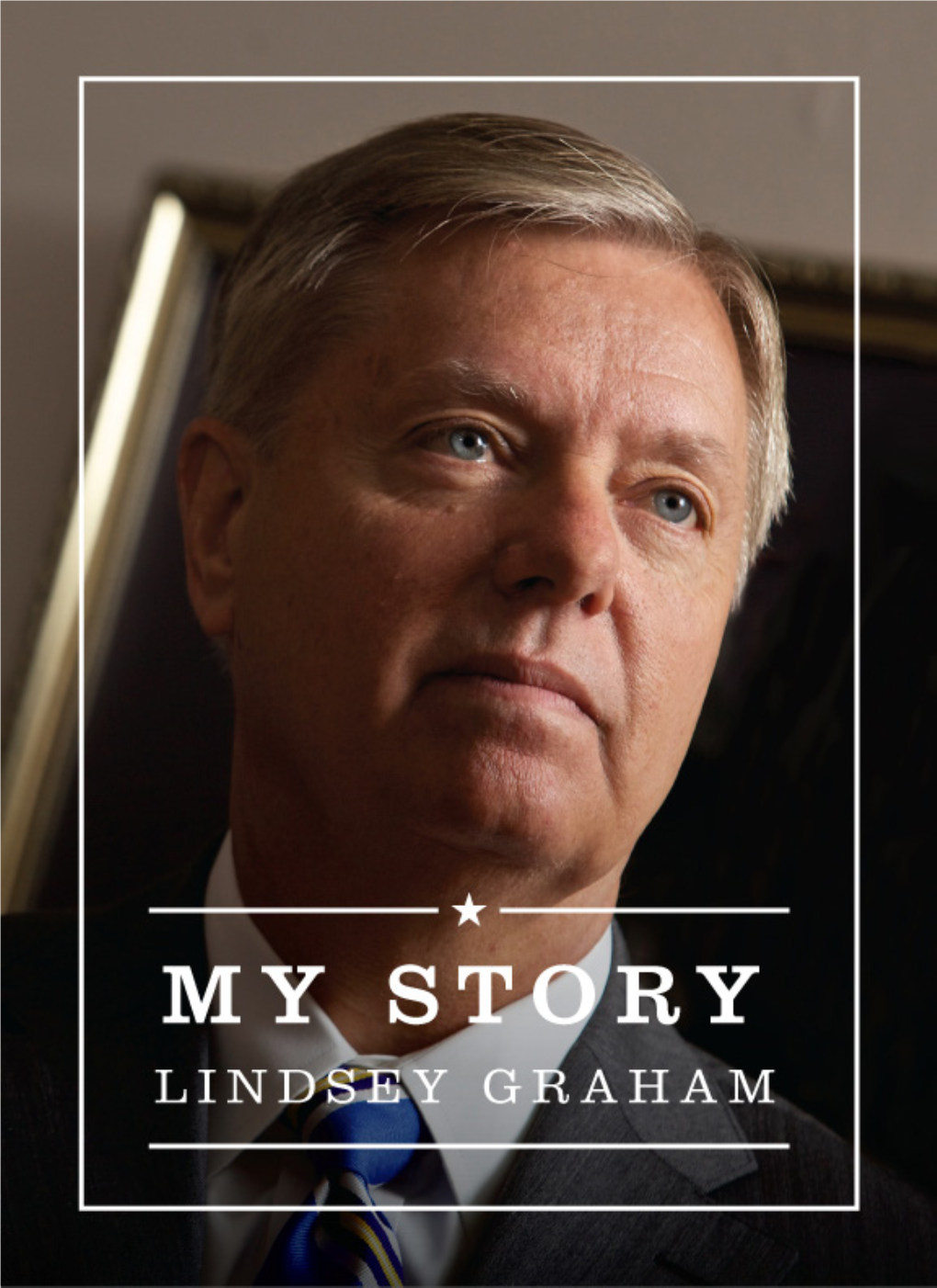

My Story, It’S My Job

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paramount Collection

Paramount Collection Airtight To control the air is to rule the world. Nuclear testing has fractured the Earth's crust, releasing poisonous gases into the atmosphere. Breathable air is now an expensive and rare commodity. A few cities have survived by constructing colossal air stacks which reach through the toxic layer to the remaining pocket of precious air above. The air is pumped into a huge underground labyrinth system, where a series of pipes to the surface feed the neighborhoods of the sealed city. It is the Air Force, known as the "tunnel hunters", that polices the system. Professor Randolph Escher has made a breakthrough in a top-secret project, the extraction of oxygen from salt water in quantity enough to return breathable air to the world. Escher is kidnapped by business tycoon Ed Conrad, who hopes to monopolize the secret process and make a fortune selling the air by subscription to the masses. Because Conrad Industries controls the air stacks, not subscribing to his "air service" would mean certain death. When Air Force Team Leader Flyer Lucci is murdered, his son Rat Lucci soon uncovers Conrad's involvement in his father's death and in Escher's kidnapping. Rat must go after Conrad, not only to avenge his father's murder, but to rescue Escher and his secret process as well. The loyalties of Rat's Air Force colleagues are questionable, but Rat has no choice. Alone, if necessary, he must fight for humanity's right to breathe. Title Airtight Genre Action Category TV Movie Format two hours Starring Grayson McCouch, Andrew Farlane, Tasma Walton Directed by Ian Barry Produced by Produced by Airtight Productions Proprietary Ltd. -

Raiders to Seek State Baseball Title on Saturday

SCOTCH PLAINS FANWOOD VOLUME 19 NO. 22 SCOTCH PLAINS • FANWOOD, N.J. THURSDAY, JUNE 9; 1977 20 CENTS f t Carnival" At H.S. Raiders To Seek State Baseball Title On Saturday Coach And Team Are Daily News Choices The Blue Raiders of Scotch Plains-Fanwood High School are but a game away from the state championship for Group 4 (largest) high schools in the state. The championship game will be played on Satur- day, June 11 at Mercer County Park in Trenton, when the Raiders meet Piseataway. The Raiders qualified for the June 3. finals on Tuesday, June 7, when they topped Bergenfield, 3-2, Westfield had won two of the behind the fine pitching of Ed previous three games, but the Reilly. Reilly gave up three hits Raiders were ready this time, as en route to his tenth victory. The they won 2-1. Reilly was on the Raiders scored all their runs in mound for the SP-F team, and the first inning. turned in a superb performance, Scott Rodgers singled sharply giving up two hits in the full A "carnival" atmosphere will prevail at Scotch Plains-Fanwood High this weekend, as the seniors present to left, then Tim Laspe followed seven innings. the musical "Carnival" as their senior play. The chorus is in rehearsal above. See them in real life, carnival with a walk. Reilly then blasted a Wesifield scored first, but the costume, in the high school auditorium, June 10 and 11, at 8 pm. long homerun to give the Raiders came back, led by Raiders the lead. -

1. Richie Ashburn (April 11, 1962) 60

1. Richie Ashburn (April 11, 1962) 60. Joe Hicks (July 12, 1963) 117. Dick Rusteck (June 10, 1966) 2. Felix Mantilla 61. Grover Powell (July 13, 1963) 118. Bob Shaw (June 13, 1966) 3. Charlie Neal 62. Dick Smith (July 20, 1963) 119. Bob Friend (June 18, 1966) 4. Frank Thomas 63. Duke Carmel (July 30, 1963) 120. Dallas Green (July 23, 1966) 5. Gus Bell 64. Ed Bauta (August 11, 1963) 121. Ralph Terry (August 11, 1966) 6. Gil Hodges 65. Pumpsie Green (September 4, 1963) 122. Shaun Fitzmaurice (September 9, 1966) 7. Don Zimmer 66. Steve Dillon (September 5, 1963) 123. Nolan Ryan (September 11, 1966) 8. Hobie Landrith 67. Cleon Jones (September 14, 1963) --- 9. Roger Craig --- 124. Don Cardwell (April 11, 1967) 10. Ed Bouchee 68. Amado Samuel (April 14, 1964) 125. Don Bosch 11. Bob Moorhead 69. Hawk Taylor 126. Tommy Davis 12. Herb Moford 70. John Stephenson 127. Jerry Buchek 13. Clem Labine 71. Larry Elliot (April 15, 1964) 128. Tommie Reynolds 14. Jim Marshall 72. Jack Fisher (April 17, 1964) 129. Don Shaw 15. Joe Ginsberg (April 13, 1962) 73. George Altman 130. Tom Seaver (April 13, 1967) 16. Sherman Jones 74. Jerry Hinsley (April 18, 1964) 131. Chuck Estrada 17. Elio Chacon 75. Bill Wakefield 132. Larry Stahl 18. John DeMerit 76. Ron Locke (April 23, 1964) 133. Sandy Alomar 19. Ray Daviault 77. Charley Smith (April 24, 1964) 134. Ron Taylor 20. Bobby Smith 78. Roy McMillan (May 9, 1964) 135. Jerry Koosman (April 14, 1967) 21. Chris Cannizzaro (April 14, 1962) 79. -

Gender Constructions and Mentorship on CBS's Elementary

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2019 An Infinite Capacity for Co-consulting: Gender Constructions and Mentorship on CBS's Elementary Heather Hufford Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Recommended Citation Hufford, Heather, "An Infinite Capacity for Co-consulting: Gender Constructions and Mentorship on CBS's Elementary" (2019). All Regis University Theses. 929. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/929 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INFINITE CAPACITY FOR CO-CONSULTING: GENDER CONSTRUCTIONS AND MENTORSHIP ON CBS’S ELEMENTARY A thesis submitted to Regis College The Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors by Heather Hufford May 2019 Thesis written by Heather Hufford Approved by Thesis Advisor Thesis Reader Accepted by Director, University Honors Program ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv I. INTRODUCTION: THE FRIENDS OF SHERLOCK HOLMES 1 II. READING ELEMENTARY AS AN ATTEMPT AT PORTRAYING 12 GENDER EQUALITY III. CONFLICTING PERMEABILITIES IN PATERNAL MENTORSHIPS 34 IN “RIP OFF” IV. INTERACTIONS BETWEEN GENDERED SPACE AND 52 MENTORSHIPS IN “TERRA PERICOLOSA” V. GENDERED CONFLICTS BETWEEN HARD-BOILED AND 75 PROCEDURAL TRADITIONS IN “THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY” WORKS CITED 110 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the conclusion of “The Five Orange Pipz,” Elementary’s Sherlock Holmes remarks, “They say that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains. -

LEASK-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (1.565Mb)

WRAITHS AND WHITE MEN: THE IMPACT OF PRIVILEGE ON PARANORMAL REALITY TELEVISION by ANTARES RUSSELL LEASK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2020 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Timothy Morris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Timothy Richardson Copyright by Antares Russell Leask 2020 Leask iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • I thank my Supervising Committee for being patient on this journey which took much more time than expected. • I thank Dr. Tim Morris, my Supervising Professor, for always answering my emails, no matter how many years apart, with kindness and understanding. I would also like to thank his demon kitten for providing the proper haunted atmosphere at my defense. • I thank Dr. Neill Matheson for the ghostly inspiration of his Gothic Literature class and for helping me return to the program. • I thank Dr. Tim Richardson for using his class to teach us how to write a conference proposal and deliver a conference paper – knowledge I have put to good use! • I thank my high school senior English teacher, Dr. Nancy Myers. It’s probably an urban legend of my own creating that you told us “when you have a Ph.D. in English you can talk to me,” but it has been a lifetime motivating force. • I thank Dr. Susan Hekman, who told me my talent was being able to use pop culture to explain philosophy. It continues to be my superpower. • I thank Rebecca Stone Gordon for the many motivating and inspiring conversations and collaborations. • I thank Tiffany A. -

Eternal Marriage Student Manual

ETERNAL MARRIAGE STUDENT MANUAL Religion 234 and 235 ETERNAL MARRIAGE STUDENT MANUAL Preparing for an Eternal Marriage, Religion 234 Building an Eternal Marriage, Religion 235 Prepared by the Church Educational System Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Send comments and corrections, including typographic errors, to CES Editing, 50 E. North Temple Street, Floor 8, Salt Lake City, UT 84150-2772 USA. E-mail: [email protected] © 2001, 2003 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 6/03 CONTENTS Preface Communication Using the Student Manual . viii Related Scriptures . 31 Purpose of the Manual . viii Selected Teachings . 31 Organization of the Manual . viii Family Communications, Living by Gospel Principles . viii Elder Marvin J. Ashton . 32 Abortion Listen to Learn, Elder Russell M. Nelson . 35 Selected Teachings . 1 Covenants and Ordinances Abuse Selected Teachings . 38 Selected Teachings . 3 Keeping Our Covenants . 38 Abuse Defined . 3 Our Covenant-Based Relationship with the Lord . 40 Policy toward Abuse . 3 Wayward Children Born under Causes of Abuse . 3 the Covenant . 47 Avoiding Abuse . 4 Covenant Marriage, Elder Bruce C. Hafen . 47 Healing the Tragic Scars of Abuse, Dating Standards Elder Richard G. Scott . 5 Selected Teachings . 51 Adjustments in Marriage For the Strength of Youth: Fulfilling Selected Teachings . 9 Our Duty to God, booklet . 52 Adjusting to In-Laws . 9 Debt Financial Adjustments . 9 Related Scriptures . 59 Adjusting to an Intimate Relationship . 9 Selected Teachings . 59 Related Scriptures . .10 To the Boys and to the Men, Atonement and Eternal Marriage President Gordon B. -

My Replay Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition- May 2014

My Replay Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition- May 2014 A complete record of my full-season Replays of the 1908, 1952, 1956, 1960, 1966, 1967, 1975, and 1978 Major League seasons as well as the 1923 Negro National League season. This encyclopedia includes the following sections: • A list of no-hitters • A season-by season recap in the format of the Neft and Cohen Sports Encyclopedia- Baseball • Top ten single season performances in batting and pitching categories • Career top ten performances in batting and pitching categories • Complete career records for all batters • Complete career records for all pitchers Table of Contents Page 3 Introduction 4 No-hitter List 5 Neft and Cohen Sports Encyclopedia Baseball style season recaps 91 Single season record batting and pitching top tens 93 Career batting and pitching top tens 95 Batter Register 277 Pitcher Register Introduction My baseball board gaming history is a fairly typical one. I lusted after the various sports games advertised in the magazines until my mom finally relented and bought Strat-O-Matic Football for me in 1972. I got SOM’s baseball game a year later and I was hooked. I would get the new card set each year and attempt to play the in-progress season by moving the traded players around and turning ‘nameless player cards” into that year’s key rookies. I switched to APBA in the late ‘70’s because they started releasing some complete old season sets and the idea of playing with those really caught my fancy. Between then and the mid-nineties, I collected a lot of card sets. -

Beacon Dec Jan 2012 Layout

The Beacon 106 Years as “A Light in the Hills” NO. 3 RIVERSIDE CHRISTIAN SCHOOL LOST CREEK, KY 41348 DECEMBER/JANUARY 2012 25 CENTS Riverside family loses two It was just another Monday. Kayla, 13, were taken to the several other capacities when It was just a trip to WalMart to University of Kentucky Chil- there was a need. get some glue. dren’s Hospital in Lexington. Shirley and Zane both have Certainly no one suspected Curtis died Tuesday after- had a great love for young that January 2, 2012 would turn noon. people for many years. They into a day of tragedy for one This is a great loss for their have always had an open door special family and a very large family, especially Shirley’s policy at their home in Lost extended family. husband Zane, their two Creek. Zane is a retired That afternoon Shirley Watts daughters Stephani and teacher. and two of her grand-children, Tracy, plus Kayla and other Curtis, a fourth grader at Curtis and Kayla, were head- grandchildren. Riverside School, was an en- ing south on Route 15 in It is also a great loss for ergetic, fun-loving boy. He neighboring Perry County. Riverside Christian School. was a member of the Lower Their vehicle hit a patch of Shirley had been working in Lights, Riverside’s traveling ice, went out of control, the school library. Although choir. crossed the center line, and col- not a certified librarian, she Kayla, an eighth grader, lided with a vehicle in the had quickly learned the pro- survived the accident. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 24, 2018 to Sun. September 30, 2018

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 24, 2018 to Sun. September 30, 2018 Monday September 24, 2018 Premiere 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT 9:00 PM ET / 6:00 PM PT Nashville The English Patient I Saw The Light - Rayna brings her kids and sister on tour, but doesn’t like the effect Juliette is A tragic and torrid love affair is recounted in a small Italian villa during the closing days of having on her girls; Juliette starts to look at Dante differently; Deacon reconsiders life on the World War II in Anthony Minghella’s Oscar winning epic drama. Starring Ralph Fiennes, Juliette road; a handsome new neighbor befriends Gunnar and Scarlett. Binoche, and Kristin Scott Thomas. Directed by Anthony Minghella. (1996 - R) 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 12:00 AM ET / 9:00 PM PT The Big Interview The X Factor UK Neil Young - Music legend Neil Young sits down for a rare and candid interview about his career, Audition Show 8 - The X Factor UK is back for its 15th season to find the next big star! his music and his environmental activism. 1:00 AM ET / 10:00 PM PT 10:00 AM ET / 7:00 AM PT The English Patient Bruce Springsteen And The E Street Band: Live In Barcelona A tragic and torrid love affair is recounted in a small Italian villa during the closing days of Recorded in 2002, touring behind the timeless album The Rising, Bruce Springsteen and the E World War II in Anthony Minghella’s Oscar winning epic drama. -

South's High School Leaders Meet in Georgetown Secret Service Seizes

tf South's High School Leaders Meet In Georgetown If you see a lot of new and for a busy schedule that ends Sat M. today with a general session eral session on the theme "The session at 9 A. M., when Gerald political rally for the candidates EDITORIAL fine-looking teenage faces in urday with the southern associa that finds Mayor O. M. Higgins, American Way—Liberty's Pride." Van Pool, director of the National for office in the south-wide as Georgetown this weekend, do not tion's election of officers for the Georgetown County Senator C. C Later today discussion groups Association of Student Councils sociation. be surprised. coming year. Grimes and Winyah High Princi will be conducted to delve into from Washington and Herman Al New officers will be chosen at Winyah High School is host to Georgetonians have responded pal Harvey I. Rice, Jr., welcoming such topics as school spirit and dridge, International Paper Com the third general session Saturday Glad To See You the Southern Association of Stu to the convention with a heart, visiting students and adults to honor systems. A banquet is pany's general counsel in Mobile, when the Rev. Jerry Hammet, dent Councils for the first annual opening their homes to house the Georgetown County. planned at 6 P. M. tonight to be deliver the principal addresses. from the University of South Car convention to be held in South many delegates visiting here. The President/ I the Southern followed by a dance from 8 to During the day, panel dicussions olina's Westminister Fellowship To the scores of teeriage student council leaders Carolina in over 11 years. -

Typologies of Evil in the X-Files

TYPOLOGIES OF EVIL IN THE X-FILES BY MAGNE HÅLAND SUPERVISOR: PAUL LEER SALVESEN AND SOLVEIG AASEN UNIVERSITY OF AGDER 2019 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND EDUCATION DEPARTEMENT OF RELIGION, PHILOSOPHY AND HISTORY 0 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express great appreciation to my supervisors, Professor Paul Leer-Salvesen (University of Agder) and Solveig Aasen, PhD in philosophy (University of Oslo), for their valuable and constructive suggestions during the development of this research work. I would also like to express my deep gratitude to my colleagues at Arendal Upper Secondary School, Steinar Tvedt, Inger Johanne Hermansen, Ane Kristine Bruland and Ida Wullum for their patient guidance and useful critique of my writing in English. Finally, I wish to thank my father, a proud working-class man, for his support and encouragement throughout my whole life. Throughout his life, he was never able to read English. Therefore, he “forced” me to translate my work for him. The Nazi-form of evil with Himmler, Mengele and Eichmann concerned him. Often, he asked me, how could a man (Eichmann) be that blinded? Without my father giving me motivation, I would never have come this far in my studies. 1 CONTENTS ABSTRACT …..5 CHAPTER 1, INTRODUCTION 1.1) General introduction of evil in movies …..6-7 1.2) My Research Question ……7 1.3) A short overview on the typologies of evil …..7-9 1.4) Defining evil …..9-10 1.5) A critique and defense of evil ….10-12 1.6) What is The X-files about? ….12-14 1.7) Why explore The X-Files? …..14-15 CHAPTER 2, METHODS 2.1) Theory and applied ethics …..16-18 2.2) Specific evil episodes as subjects for research and constructing analysis chapters ..18-19 2.3) The importance of using scientific work related to movies and evil …..19-21 2.4) Methodological inspiration for my thesis, work done by Dean A. -

1977 Roster Sheet.Xlsx

NATIONAL LEAGUE TEAM ROSTERS (page 1 of 2) ATLANTA BRAVES CHICAGO CUBS CINCINNATI REDS HOUSTON ASTROS LOS ANGELES DODGERS MONTREAL EXPOS NEW YORK METS Batter Cards (18) Batter Cards (15) Batter Cards (16) Batter Cards (17) Batter Cards (18) Batter Cards (19) Batter Cards (20) Brian Asselstine Larry Biittner Ed Armbrister Ken Boswell Dusty Baker Tim Blackwell 2 Bruce Boisclair Barry Bonnell Bill Buckner Rick Auerbach Enos Cabell Glenn Burke Gary Carter Doug Flynn 2 Jeff Burroughs Jose Cardenal Bob Bailey 1 Cesar Cedeno Ron Cey Dave Cash Leo Foster Darrel Chaney Gene Clines Johnny Bench Willie Crawford 1 Vic Davalillo Warren Cromartie Jerry Grote 1 Vic Correll Ivan DeJesus Dave Concepcion Jose Cruz Steve Garvey Andre Dawson Bud Harrelson Cito Gaston Greg Gross Dan Driessen Joe Ferguson Ed Goodson Tim Foli 1 Steve Henderson Rod Gilbreath Mick Kelleher Doug Flynn 1 Jim Fuller Jerry Grote 2 Barry Foote 1 Ron Hodges Gary Matthews George Mitterwald George Foster Art Gardner John Hale Pepe Frias Dave Kingman 1 Willie Montanez Jerry Morales Cesar Geronimo Julio Gonzalez Lee Lacy Wayne Garrett Ed Kranepool Junior Moore Bobby Murcer Ken Griffey Ed Herrmann Davey Lopes Mike Jorgensen 1 Lee Mazzilli Dale Murphy Steve Ontiveros Ray Knight Wilbur Howard Ted Martinez Pete Mackanin Felix Millan Joe Nolan Dave Rosello Mike Lum Art Howe Rick Monday Sam Mejias John Milner Rowland Office Steve Swisher Joe Morgan Cliff Johnson 1 Manny Mota Jose Morales Mike Phillips 1 Tom Paciorek Manny Trillo Bill Plummer Roger Metzger Johnny Oates Stan Papi Len Randle Biff