ESCMID Online Lecture Library © by Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks Bioblitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of BioBlitz participants conducting data entry into iNaturalist. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service. ON THE COVER Photograph of BioBlitz participants collecting aquatic species data in the Presidio of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service. The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 Elizabeth Edson1, Michelle O’Herron1, Alison Forrestel2, Daniel George3 1Golden Gate Parks Conservancy Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94129 2National Park Service. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1061 Sausalito, CA 94965 3National Park Service. San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program Manager Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1063 Sausalito, CA 94965 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Pinpointing the Origin of Mitochondria Zhang Wang Hanchuan, Hubei

Pinpointing the origin of mitochondria Zhang Wang Hanchuan, Hubei, China B.S., Wuhan University, 2009 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Biology University of Virginia August, 2014 ii Abstract The explosive growth of genomic data presents both opportunities and challenges for the study of evolutionary biology, ecology and diversity. Genome-scale phylogenetic analysis (known as phylogenomics) has demonstrated its power in resolving the evolutionary tree of life and deciphering various fascinating questions regarding the origin and evolution of earth’s contemporary organisms. One of the most fundamental events in the earth’s history of life regards the origin of mitochondria. Overwhelming evidence supports the endosymbiotic theory that mitochondria originated once from a free-living α-proteobacterium that was engulfed by its host probably 2 billion years ago. However, its exact position in the tree of life remains highly debated. In particular, systematic errors including sparse taxonomic sampling, high evolutionary rate and sequence composition bias have long plagued the mitochondrial phylogenetics. This dissertation employs an integrated phylogenomic approach toward pinpointing the origin of mitochondria. By strategically sequencing 18 phylogenetically novel α-proteobacterial genomes, using a set of “well-behaved” phylogenetic markers with lower evolutionary rates and less composition bias, and applying more realistic phylogenetic models that better account for the systematic errors, the presented phylogenomic study for the first time placed the mitochondria unequivocally within the Rickettsiales order of α- proteobacteria, as a sister clade to the Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae families, all subtended by the Holosporaceae family. -

Abstract Betaproteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria

Abstract N-210 Contact Information The majority of the soil’s biosphere containins biodiveristy that remains yet to be discovered. The occurrence of novel bacterial phyla in soil, as well as the phylogenetic diversity within bacterial phyla with few cultured representatives (e.g. Acidobacteria, Anne Spain Dr. Mostafa S.Elshahed Verrucomicrobia, and Gemmatimonadetes) have been previously well documented. However, few studies have focused on the Composition, Diversity, and Novelty within Soil Proteobacteria Department of Botany and Microbiology Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics novel phylogenetic diversity within phyla containing numerous cultured representatives. Here, we present a detailed University of Oklahoma Oklahoma State University phylogenetic analysis of the Proteobacteria-affiliated clones identified in a 13,001 nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene clones 770 Van Vleet Oval 307 LSE derived from Oklahoma tall grass prairie soil. Proteobacteria was the most abundant phylum in the community, and comprised Norman, OK 73019 Stillwater, OK 74078 25% of total clones. The most abundant and diverse class within the Proteobacteria was Alphaproteobacteria, which comprised 405 325 5255 405 744 6790 39% of Proteobacteria clones, followed by the Deltaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, and Gammaproteobacteria, which made Anne M. Spain (1), Lee R. Krumholz (1), Mostafa S. Elshahed (2) up 37, 16, and 8% of Proteobacteria clones, respectively. Members of the Epsilonproteobacteria were not detected in the dataset. [email protected] [email protected] Detailed phylogenetic analysis indicated that 14% of the Proteobacteria clones belonged to 15 novel orders and 50% belonged (1) Dept. of Botany and Microbiology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK to orders with no described cultivated representatives or were unclassified. -

“Candidatus Deianiraea Vastatrix” with the Ciliate Paramecium Suggests

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/479196; this version posted November 27, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The extracellular association of the bacterium “Candidatus Deianiraea vastatrix” with the ciliate Paramecium suggests an alternative scenario for the evolution of Rickettsiales 5 Castelli M.1, Sabaneyeva E.2, Lanzoni O.3, Lebedeva N.4, Floriano A.M.5, Gaiarsa S.5,6, Benken K.7, Modeo L. 3, Bandi C.1, Potekhin A.8, Sassera D.5*, Petroni G.3* 1. Centro Romeo ed Enrica Invernizzi Ricerca Pediatrica, Dipartimento di Bioscienze, Università 10 degli studi di Milano, Milan, Italy 2. Department of Cytology and Histology, Faculty of Biology, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint-Petersburg, Russia 3. Dipartimento di Biologia, Università di Pisa, Pisa, Italy 4 Centre of Core Facilities “Culture Collections of Microorganisms”, Saint Petersburg State 15 University, Saint Petersburg, Russia 5. Dipartimento di Biologia e Biotecnologie, Università degli studi di Pavia, Pavia, Italy 6. UOC Microbiologia e Virologia, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy 7. Core Facility Center for Microscopy and Microanalysis, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint- Petersburg, Russia 20 8. Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Biology, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint- Petersburg, Russia * Corresponding authors, contacts: [email protected] ; [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/479196; this version posted November 27, 2018. -

Evolutionary Origin of Insect–Wolbachia Nutritional Mutualism

Evolutionary origin of insect–Wolbachia nutritional mutualism Naruo Nikoha,1, Takahiro Hosokawab,1, Minoru Moriyamab,1, Kenshiro Oshimac, Masahira Hattoric, and Takema Fukatsub,2 aDepartment of Liberal Arts, The Open University of Japan, Chiba 261-8586, Japan; bBioproduction Research Institute, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Tsukuba 305-8566, Japan; and cCenter for Omics and Bioinformatics, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, University of Tokyo, Kashiwa 277-8561, Japan Edited by Nancy A. Moran, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, and approved June 3, 2014 (received for review May 20, 2014) Obligate insect–bacterium nutritional mutualism is among the insects, generally conferring negative fitness consequences to most sophisticated forms of symbiosis, wherein the host and the their hosts and often causing hosts’ reproductive aberrations to symbiont are integrated into a coherent biological entity and un- enhance their own transmission in a selfish manner (7, 8). Re- able to survive without the partnership. Originally, however, such cently, however, a Wolbachia strain associated with the bedbug obligate symbiotic bacteria must have been derived from free-living Cimex lectularius,designatedaswCle, was shown to be es- bacteria. How highly specialized obligate mutualisms have arisen sential for normal growth and reproduction of the blood- from less specialized associations is of interest. Here we address this sucking insect host via provisioning of B vitamins (9). Hence, it –Wolbachia evolutionary -

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis Are Tick-Borne Diseases Caused by Obligate Anaplasmosis: Intracellular Bacteria in the Genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma

Ehrlichiosis and Importance Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are tick-borne diseases caused by obligate Anaplasmosis: intracellular bacteria in the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. These organisms are widespread in nature; the reservoir hosts include numerous wild animals, as well as Zoonotic Species some domesticated species. For many years, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species have been known to cause illness in pets and livestock. The consequences of exposure vary Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, from asymptomatic infections to severe, potentially fatal illness. Some organisms Canine Hemorrhagic Fever, have also been recognized as human pathogens since the 1980s and 1990s. Tropical Canine Pancytopenia, Etiology Tracker Dog Disease, Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are caused by members of the genera Ehrlichia Canine Tick Typhus, and Anaplasma, respectively. Both genera contain small, pleomorphic, Gram negative, Nairobi Bleeding Disorder, obligate intracellular organisms, and belong to the family Anaplasmataceae, order Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rickettsiales. They are classified as α-proteobacteria. A number of Ehrlichia and Canine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Anaplasma species affect animals. A limited number of these organisms have also Equine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, been identified in people. Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Recent changes in taxonomy can make the nomenclature of the Anaplasmataceae Tick-borne Fever, and their diseases somewhat confusing. At one time, ehrlichiosis was a group of Pasture Fever, diseases caused by organisms that mostly replicated in membrane-bound cytoplasmic Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, vacuoles of leukocytes, and belonged to the genus Ehrlichia, tribe Ehrlichieae and Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, family Rickettsiaceae. The names of the diseases were often based on the host Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, species, together with type of leukocyte most often infected. -

First Detection and Molecular Identification of the Zoonotic Anaplasma Capra In

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/482851; this version posted November 30, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 First detection and molecular identification of the zoonotic Anaplasma capra in 2 deer in France 3 4 Short title : Anaplasma capra in deer in France 5 Maggy Jouglin1, Barbara Blanc2, Nathalie de la Cotte1, Katia Ortiz2, Laurence Malandrin1* 6 1BIOEPAR, INRA, Oniris, Nantes, France 7 2Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Réserve Zoologique de la Haute Touche, Obterre, France 8 9 *corresponding author : [email protected] – Current adress : INRA/Oniris, Site 10 de la Chantrerie, CS40706, UMR BioEpAR, 44307 Nantes cedex 3, France. Tel: +(33)2 40 68 78 11 57. Fax: +(33)2 40 68 77 51. 12 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/482851; this version posted November 30, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 13 Abstract 14 Cervids are known to be reservoir of zoonotic tick-transmitted bacteria. The aim of this study was 15 to perform a survey in a wild fauna reserve to characterize Anaplasma species carried by captive red 16 deer and swamp deer. Blood from 59 red deer and 7 swamp deer was collected and analyzed over a 17 period of two years. A semi-nested PCR that targets the 23S rRNA was performed to detect and 18 characterise Anaplasma spp. -

Table S4. Phylogenetic Distribution of Bacterial and Archaea Genomes in Groups A, B, C, D, and X

Table S4. Phylogenetic distribution of bacterial and archaea genomes in groups A, B, C, D, and X. Group A a: Total number of genomes in the taxon b: Number of group A genomes in the taxon c: Percentage of group A genomes in the taxon a b c cellular organisms 5007 2974 59.4 |__ Bacteria 4769 2935 61.5 | |__ Proteobacteria 1854 1570 84.7 | | |__ Gammaproteobacteria 711 631 88.7 | | | |__ Enterobacterales 112 97 86.6 | | | | |__ Enterobacteriaceae 41 32 78.0 | | | | | |__ unclassified Enterobacteriaceae 13 7 53.8 | | | | |__ Erwiniaceae 30 28 93.3 | | | | | |__ Erwinia 10 10 100.0 | | | | | |__ Buchnera 8 8 100.0 | | | | | | |__ Buchnera aphidicola 8 8 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pantoea 8 8 100.0 | | | | |__ Yersiniaceae 14 14 100.0 | | | | | |__ Serratia 8 8 100.0 | | | | |__ Morganellaceae 13 10 76.9 | | | | |__ Pectobacteriaceae 8 8 100.0 | | | |__ Alteromonadales 94 94 100.0 | | | | |__ Alteromonadaceae 34 34 100.0 | | | | | |__ Marinobacter 12 12 100.0 | | | | |__ Shewanellaceae 17 17 100.0 | | | | | |__ Shewanella 17 17 100.0 | | | | |__ Pseudoalteromonadaceae 16 16 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pseudoalteromonas 15 15 100.0 | | | | |__ Idiomarinaceae 9 9 100.0 | | | | | |__ Idiomarina 9 9 100.0 | | | | |__ Colwelliaceae 6 6 100.0 | | | |__ Pseudomonadales 81 81 100.0 | | | | |__ Moraxellaceae 41 41 100.0 | | | | | |__ Acinetobacter 25 25 100.0 | | | | | |__ Psychrobacter 8 8 100.0 | | | | | |__ Moraxella 6 6 100.0 | | | | |__ Pseudomonadaceae 40 40 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pseudomonas 38 38 100.0 | | | |__ Oceanospirillales 73 72 98.6 | | | | |__ Oceanospirillaceae -

Ultrastructure and Localization of Neorickettsia in Adult Digenean

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2017 Ultrastructure and localization of Neorickettsia in adult digenean trematodes provides novel insights into helminth-endobacteria interaction Kerstin Fischer Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Vasyl V. Tkach University of North Dakota Kurt C. Curtis Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Peter U. Fischer Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Recommended Citation Fischer, Kerstin; Tkach, Vasyl V.; Curtis, Kurt C.; and Fischer, Peter U., ,"Ultrastructure and localization of Neorickettsia in adult digenean trematodes provides novel insights into helminth-endobacteria interaction." Parasites & Vectors.10,. 177. (2017). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/5789 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fischer et al. Parasites & Vectors (2017) 10:177 DOI 10.1186/s13071-017-2123-7 RESEARCH Open Access Ultrastructure and localization of Neorickettsia in adult digenean trematodes provides novel insights into helminth- endobacteria interaction Kerstin Fischer1, Vasyl V. Tkach2, Kurt C. Curtis1 and Peter U. Fischer1* Abstract Background: Neorickettsia are a group of intracellular α proteobacteria transmitted by digeneans (Platyhelminthes, Trematoda). These endobacteria can also infect vertebrate hosts of the helminths and cause serious diseases in animals and humans. Neorickettsia have been isolated from infected animals and maintained in cell cultures, and their morphology in mammalian cells has been described. -

Table S5. the Information of the Bacteria Annotated in the Soil Community at Species Level

Table S5. The information of the bacteria annotated in the soil community at species level No. Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species The number of contigs Abundance(%) 1 Firmicutes Bacilli Bacillales Bacillaceae Bacillus Bacillus cereus 1749 5.145782459 2 Bacteroidetes Cytophagia Cytophagales Hymenobacteraceae Hymenobacter Hymenobacter sedentarius 1538 4.52499338 3 Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadales Gemmatimonadaceae Gemmatirosa Gemmatirosa kalamazoonesis 1020 3.000970902 4 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas indica 797 2.344876284 5 Firmicutes Bacilli Lactobacillales Streptococcaceae Lactococcus Lactococcus piscium 542 1.594633558 6 Actinobacteria Thermoleophilia Solirubrobacterales Conexibacteraceae Conexibacter Conexibacter woesei 471 1.385742446 7 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas taxi 430 1.265115184 8 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas wittichii 388 1.141545794 9 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas sp. FARSPH 298 0.876754244 10 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sorangium cellulosum 260 0.764953367 11 Proteobacteria Deltaproteobacteria Myxococcales Polyangiaceae Sorangium Sphingomonas sp. Cra20 260 0.764953367 12 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas panacis 252 0.741416341 -

Rickettsiales Bacterial Trans-Infection from Paramecium

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/688770; this version posted July 2, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Outwitting planarian’s antibacterial defence mechanisms: 2 Rickettsiales bacterial trans-infection from Paramecium 3 multimicronucleatum to planarians 4 5 Letizia Modeo1*, Alessandra Salvetti2*, Leonardo Rossi2, Michele Castelli3, Franziska Szokoli4, 6 Sascha Krenek4,5, Elena Sabaneyeva6, Graziano Di Giuseppe1, Sergei I. Fokin1,7, Franco Verni1, 7 Giulio Petroni1 8 9 1Department of Biology, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy 10 2Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy 11 3Centro Romeo ed Enrica Invernizzi Ricerca Pediatrica, Department of Biosciences, University of 12 Milan, Milan, Italy 13 4Institute of Hydrobiology, Dresden University of Technology, Dresden, Germany 14 5Department of River Ecology, Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research - UFZ, Magdeburg, 15 Germany 16 6Department of Cytology and Histology, Faculty of Biology, Saint Petersburg State University, 17 Saint Petersburg, Russia 18 7Department of Invertebrate Zoology, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg, Russia 19 20 *Corresponding authors 21 [email protected] (LM); [email protected] (AS) 22 23 RUNNING PAGE HEAD: Rickettsiales macronuclear endosymbiont of a ciliate can transiently 24 enter planarian tissues 25 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/688770; this version posted July 2, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

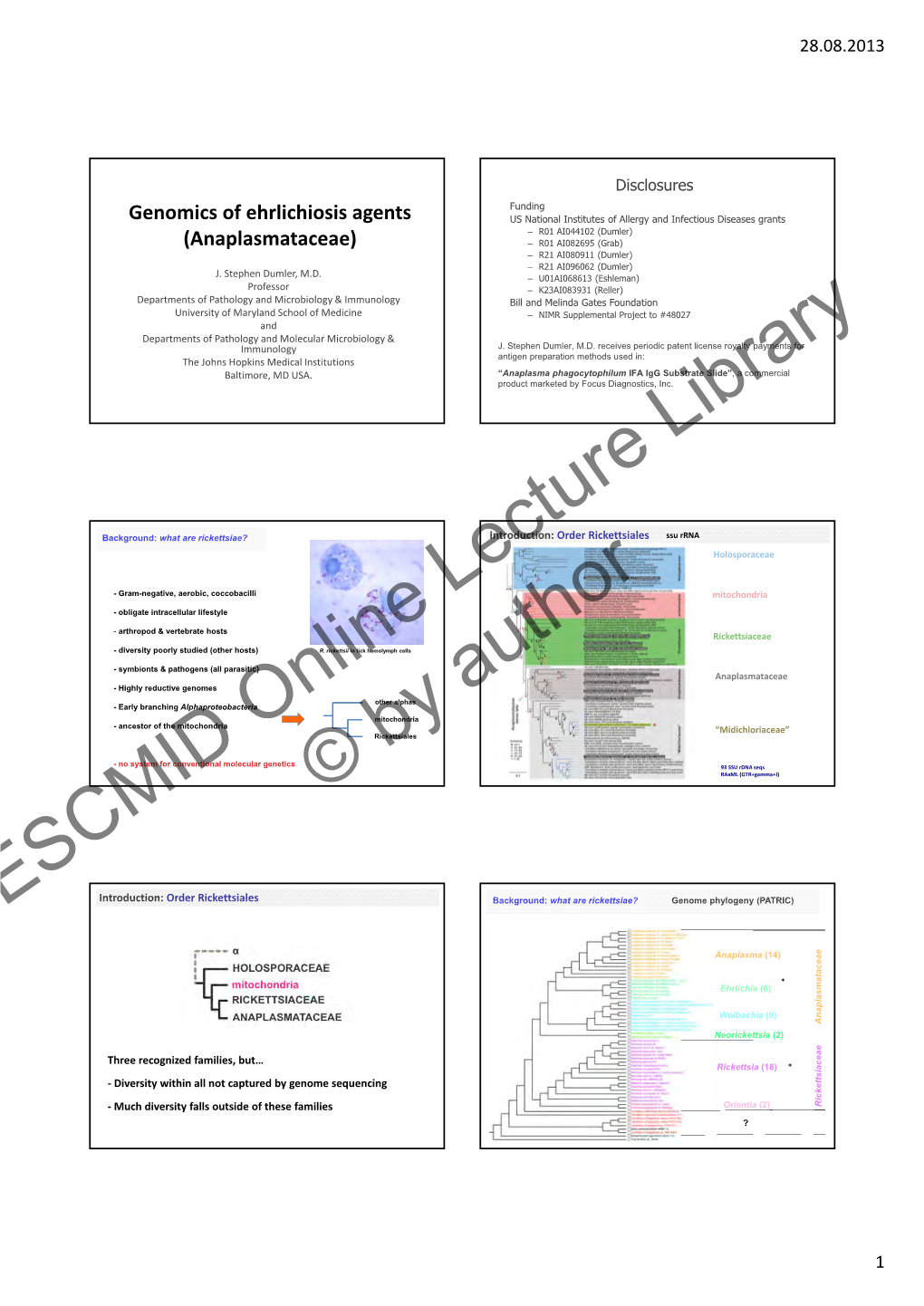

ESCMID Online Lecture Library © by Author

The order Rickettsiales Pathogenesis of “ehrlichia” (Anaplasmataceae) infections of humans •Family Rickettsiaceae • Genera Rickettsia, Orientia •Family Anaplasmatacea • Ehrlichia, Anaplasma, others J. Stephen Dumler, M.D. •obligate intracellular bacteria • -proteobacteria phylogeny by small Departments of Pathology and Microbiology & Immunology subunit RNA genes (rrs) University of Maryland School of Medicine • contain DNA, RNA, ribosomes And Departments of Pathology and Molecular Microbiology & Immunology • divide by binary fission The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions • Gram-negative cell wall Baltimore, MD USA •life cycle within arthropod host [email protected] •Bartonella (and former Rochalimaea) and Coxiella not in Rickettsiales Phylogeny of Rickettsiales (rrs) Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species infections α-proteobacteria E chaffeensis E ewingii pathogenesis A phagocytophilum E muris R prowazekii R australis • attachment R typhi R akari R felis R honei • endosomal entry R rickettsii Neoehrlichia mikurensis R conorii R parkeri W pipientis R africae R sibirica • avoidance of immediate intracellular killing (signaling) – phagolysosome fusion inhibition - doxycycline sensitive O tsutsugamushi Anaplasmataceae – subversion of autophagy Rickettsiaceae – detoxification of oxidative killing mechanisms • regulation and perturbation of host cell functions N sennetsu (gene expression) – downregulation of innate or early immune responses B quintana – cell cycle perturbations / apoptosis B henselae E coli – inhibition of intracellular trafficking