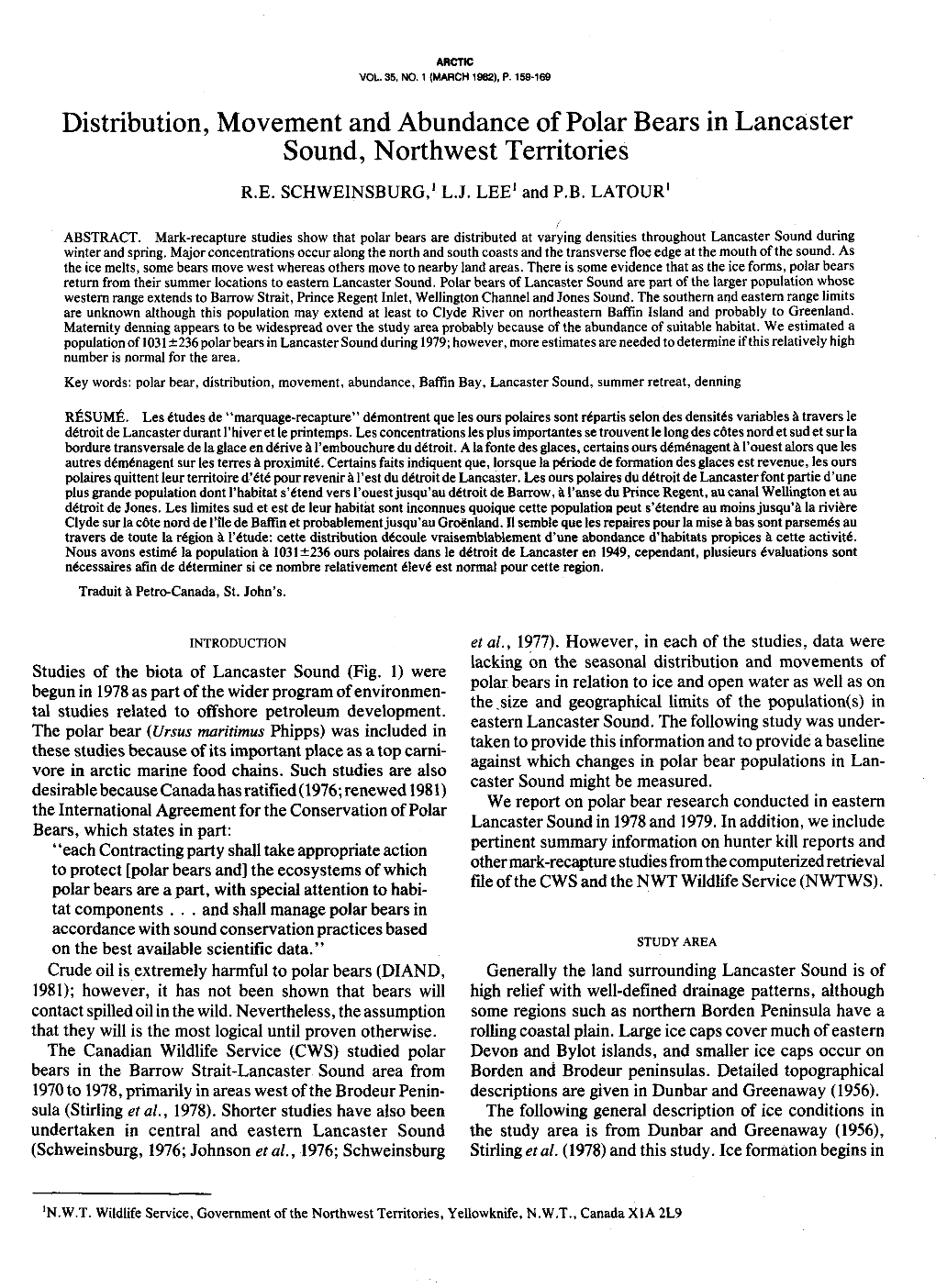

Distribution, Movement and Abundancoef Polar Bears In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Maps of Locations Mentioned in Global Review of The

Regional Maps of Locations Mentioned in Global Review of the Conservation Status of Monodontid Stocks These maps provide the locations of the geographic features mentioned in the Global Review of the Conservation Status of Monodontid Stocks. Figure 1. Locations associated with beluga stocks of the Okhotsk Sea (beluga stocks 1-5). Numbered locations are: (1) Amur River, (2) Ul- bansky Bay, (3) Tugursky Bay, (4) Udskaya Bay, (5) Nikolaya Bay, (6) Ulban River, (7) Big Shantar Island, (8) Uda River, (9) Torom River. Figure 2. Locations associated with beluga stocks of the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska (beluga stocks 6-9). Numbered locations are: (1) Anadyr River Estuary, (2) Anadyr River, (3) Anadyr City, (4) Kresta Bay, (5) Cape Navarin, (6) Yakutat Bay, (7) Knik Arm, (8) Turnagain Arm, (9) Anchorage, (10) Nushagak Bay, (11) Kvichak Bay, (12) Yukon River, (13) Kuskokwim River, (14) Saint Matthew Island, (15) Round Island, (16) St. Lawrence Island. Figure 3. Locations associated with beluga stocks of the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas, Canadian Arctic and West Greenland (beluga stocks 10-12 and 19). Numbered locations are: (1) St. Lawrence Island, (2) Kotzebue Sound, (3) Kasegaluk Lagoon, (4) Point Lay, (5) Wain- wright, (6) Mackenzie River, (7) Somerset Island, (8) Radstock Bay, (9) Maxwell Bay, (10) Croker Bay, (11) Devon Island, (12) Cunning- ham Inlet, (13) Creswell Bay, (14) Mary River Mine, (15) Elwin Bay, (16) Coningham Bay, (17) Prince of Wales Island, (18) Qeqertarsuat- siaat, (19) Nuuk, (20) Maniitsoq, (21) Godthåb Fjord, (22) Uummannaq, (23) Upernavik. Figure 4. Locations associated with beluga stocks of subarctic eastern Canada, Hudson Bay, Ungava Bay, Cumberland Sound and St. -

Western Elements in the Early Thule Culture of the Eastern High Arctic PETER SCHLEDERMANN' and KAREN Mccullough'

ARCTIC VOL. 33, NO. 4 (DECEMBER l-), P. 833-841 Western Elements in the Early Thule Culture of the Eastern High Arctic PETER SCHLEDERMANN' and KAREN McCULLOUGH' ABSTRACT. Excavations of Thule culture wintersites in the Bache Peninsula regionon the east coastof Ellesmere Island have yielded a numberof finds which indicate a strong relationship to cultural developments in the Bering Sea region. Specific elements under discussion include dwelling styles, clay pottery, needle cases, a brow band and harpoon heads. Evidence is presented suggesting an initial arrivalof the Thule cultureInuit in the eastern Arctic around 1050 A.D. INTRODUCTION Much has been writtenabout the origins and expansionof the Thule culture into the Canadian Arctic. That this event took place as a result of population move- ment and migration from the west is never seriously contested. However, the timing and causes of this movement are subjects of continuing debate. During the past three summers, excavations have taken placeon several Thule culture winter sites in the Bache Peninsula region onthe east coast of Ellesmere Island (Fig. 1). The winter settlements, containing approximately 150 house ruins distributed over 12 sites, span a 500 to 600 year occupation period which ended about 1700 A.D. The retreat of the Thule culture Inuit fromthis region to the more viable Thuledistrict in northwest Greenland probably marksthe final abandonment of the Canadian High Arctic as a semi-permanent settlement area. Research into the early Thule culture occupation in the study area has been one of several primary objectives, particularly in relation to the temporal and spatial &hities of the NQgdlit and Ruin Island phases initially described by Holtved (1944; 1954). -

Space Use and Movement Patterns of North Baffin Caribou

Space Use and Movement Patterns of North Baffin Caribou NWMB Project No. 03-09-01 Field Summary and Progress Report September 2011 1Deborah A. Jenkins and 2Jaylene Goorts 1Wildlife Research Biologist, Baffin Region, DoE, GN 2 Wildlife Technician, Baffin Region, DoE, GN PROJECT LEADER Deborah Jenkins, Baffin Region Wildlife Research Biologist Department of Environment, Government of Nunavut P.O. Box 400, Pond Inlet, Nunavut. Phone: (867) 899-8876 Email: [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was funded by the Department of Environment, Government of Nunavut, Baffinland Iron Mines Inc., the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, and Polar Continental Shelf Project. It was further supported by the Hunters and Trappers Organizations (HTO) from five local communities, Pond Inlet, Arctic Bay, Clyde River, Igloolik and Hall Beach and by Parks Canada. Special thanks to our pilots Louis Drapeau (2008), Matt O’Brian (2009), Elou (2010) and Maltee Dahler (2011) and engineer Jason Simms. The wildlife capture and collaring team of Heli-Horizons, Paul Dubois, Laurier Breton, and Rolland Lemieux were outstanding. Thanks to a team of observers Grigor Hope, Sheatie Tagak, Mitch Campbell, Jaypiti Inutiq, Andrew Maher, Gerry Courtemanche, Susan Breckon, Alex Millar, Jaylene Goorts, and Ben Widdowson. Personnel at the Mary River exploration camp were extremely helpful, particularly, Trevor Myers, Jim Millard, Cheryl Wray, Cliff Pilgrim, Brian Larson, Dalton Head, David McCann, Jeff Bush, Kirk Keller, Roland Landry, Wendy Wiseman, and John McLean. Thanks to the kitchen crew that feed us so well. Finally, a special thanks to Mike Kristjanson and Tim McCagherty at PCSP for their logistical support, Mitch Campbell for lending his collaring expertise when the program was initiated, to Jane Chisholm for her assistance with permits, and to Grigor Hope for technical support. -

Alaska's Nonresident Anglers, 2009-2013

Alaska’s Nonresident Anglers, 2009‐2013 For: Alaska Department of Fish and Game By: Southwick Associates October 2014 PO Box 6435 Fernandina Beach, FL32035 Tel (904) 277‐9765 www.southwickassociates.com Contents List of Tables .................................................................................................................................................................. ii List of Charts .................................................................................................................................................................. ii Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview of Findings ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 Gender and Age ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Country and State of Residence .................................................................................................................................... 3 Overview of Nonresident Anglers’ Country and State of Residence ......................................................................... 3 Country of Residence ................................................................................................................................................ -

A Hans Krüger Arctic Expedition Cache on Axel Heiberg Island, Nunavut ROBERT W

ARCTIC VOL. 60, NO. 1 (MARCH 2007) P. 1–6 A Hans Krüger Arctic Expedition Cache on Axel Heiberg Island, Nunavut ROBERT W. PARK1 and DOUGLAS R. STENTON2 (Received 13 June 2006; accepted in revised form 31 July 2006) ABSTRACT. In 1999 a team of geologists discovered an archaeological site near Cape Southwest, Axel Heiberg Island. On the basis of its location and the analysis of two artifacts removed from the site, the discoverers concluded that it was a hastily abandoned campsite created by Hans Krüger’s German Arctic Expedition, which was believed to have disappeared between Meighen and Amund Ringnes islands in 1930. If the attribution to Krüger were correct, the existence of this site would demonstrate that the expedition got farther on its return journey to Bache Peninsula than previously believed. An archaeological investigation of the site by the Government of Nunavut in 2004 confirmed its tentative attribution to the German Arctic Expedition but suggested that it is not a campsite, but the remains of a deliberately and carefully constructed cache. The finds suggest that one of the three members of the expedition may have perished before reaching Axel Heiberg Island, and that the survivors, in order to lighten their sledge, transported valued but heavy items (including Krüger’s geological specimens) to this prominent and well-known location to cache them, intending to return and recover them at some later date. Key words: German Arctic Expedition, Hans Krüger, archaeology, geology, Axel Heiberg Island, Nunavut RÉSUMÉ. En 1999, une équipe de géologues a découvert un lieu d’importance archéologique près du cap Southwest, sur l’île Axel Heiberg. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Wolf-Sightings on the Canadian Arctic Islands FRANK L

ARCTIC VOL. 48, NO.4 (DECEMBER 1995) P. 313–323 Wolf-Sightings on the Canadian Arctic Islands FRANK L. MILLER1 and FRANCES D. REINTJES1 (Received 6 April 1994; accepted in revised form 13 March 1995) ABSTRACT. A wolf-sighting questionnaire was sent to 201 arctic field researchers from many disciplines to solicit information on observations of wolves (Canis lupus spp.) made by field parties on Canadian Arctic Islands. Useable responses were obtained for 24 of the 25 years between 1967 and 1991. Respondents reported 373 observations, involving 1203 wolf-sightings. Of these, 688 wolves in 234 observations were judged to be different individuals; the remaining 515 wolf-sightings in 139 observations were believed to be repeated observations of 167 of those 688 wolves. The reported wolf-sightings were obtained from 1953 field-weeks spent on 18 of 36 Arctic Islands reported on: no wolves were seen on the other 18 islands during an additional 186 field-weeks. Airborne observers made 24% of all wolf-sightings, 266 wolves in 48 packs and 28 single wolves. Respondents reported seeing 572 different wolves in 118 separate packs and 116 single wolves. Pack sizes averaged 4.8 ± 0.28 SE and ranged from 2 to 15 wolves. Sixty-three wolf pups were seen in 16 packs, with a mean of 3.9 ± 2.24 SD and a range of 1–10 pups per pack. Most (81%) of the different wolves were seen on the Queen Elizabeth Islands. Respondents annually averaged 10.9 observations of wolves ·100 field-weeks-1 and saw on average 32.2 wolves·100 field-weeks-1· yr -1 between 1967 and 1991. -

P0001-P0046.Pdf

BIRD-BANDING A JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION VoL XXXII January, 1961 No. 1 STUDIES OF THE BREEDING BIOLOGY OF HORNED LARK, WATER PIPIT, LAPLAND LONGSPUR, AND SNOW BUNTING ON BYLOT ISLAND, NORTHWEST TERRITORIES, CANADA By WILLIAM H. DRURY,Ja. INTRODUCTION This paperis dividedinto threeparts. The first part reportsdetailed observationson the breedingbiology of the four species.I haveincluded many detailsbecause they showecological factors deserving discussion, and behaviordifferences suggesting unexpected geographical variation. The secondpart discussesecological questions such as how the four speciessurvive together without competition, what adaptationsallow them to breed successfullyin the Arctic; and what is the relation of large northernclutch-sizes to annualproduction and the shortbreeding season. The third part comparesthe courtshipbehavior of LaplandLongspurs with studiesof other buntings,specifically Andrew's (1957) aviary studies.These comparisons suggest either that thereare unusuallylarge geographicaland interspeciesdifferences among buntings, or that their evolutionaryrelations are not clear. Thereappear to be adaptivechanges in territorialbehavior during the early part of the longspur'sbreeding cycle. The 1954Bylot Island Expedition spent from 12 Juneto 29 Julyat the mouthof the AktineqRiver, southernBylot Island,approximately 73 ø North Latitude, 79ø West Longitude,District of Franklin, Northwest Territories,Canada. Bylot Islandis on the borderbetween the Low and High Arctic areas.and is just northof the north coastof BaitinIsland (see map in Miller, 1955). Shortdescriptions of the trip (Drurys, 1955) and of the area (Van Tyne and Drury, 1959) havebeen published. A popularaccount of certainaspects of the expeditionhas beenpu,blished as Springon an Arctic Island by KatharineScherman (1956). The observationsin this paper were madeby William and Mary Drury, and Dr. BenjaminFerris, who concentratedtheir time on the breedingbirds; and by JosselynVan Tyne,who contributed infor.mation gatheredon daily collecting trips. -

Polar Continental Shelf Program Science Report 2019: Logistical Support for Leading-Edge Scientific Research in Canada and Its Arctic

Polar Continental Shelf Program SCIENCE REPORT 2019 LOGISTICAL SUPPORT FOR LEADING-EDGE SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH IN CANADA AND ITS ARCTIC Polar Continental Shelf Program SCIENCE REPORT 2019 Logistical support for leading-edge scientific research in Canada and its Arctic Polar Continental Shelf Program Science Report 2019: Logistical support for leading-edge scientific research in Canada and its Arctic Contact information Polar Continental Shelf Program Natural Resources Canada 2464 Sheffield Road Ottawa ON K1B 4E5 Canada Tel.: 613-998-8145 Email: [email protected] Website: pcsp.nrcan.gc.ca Cover photographs: (Top) Ready to start fieldwork on Ward Hunt Island in Quttinirpaaq National Park, Nunavut (Bottom) Heading back to camp after a day of sampling in the Qarlikturvik Valley on Bylot Island, Nunavut Photograph contributors (alphabetically) Dan Anthon, Royal Roads University: page 8 (bottom) Lisa Hodgetts, University of Western Ontario: pages 34 (bottom) and 62 Justine E. Benjamin: pages 28 and 29 Scott Lamoureux, Queen’s University: page 17 Joël Bêty, Université du Québec à Rimouski: page 18 (top and bottom) Janice Lang, DRDC/DND: pages 40 and 41 (top and bottom) Maya Bhatia, University of Alberta: pages 14, 49 and 60 Jason Lau, University of Western Ontario: page 34 (top) Canadian Forces Combat Camera, Department of National Defence: page 13 Cyrielle Laurent, Yukon Research Centre: page 48 Hsin Cynthia Chiang, McGill University: pages 2, 8 (background), 9 (top Tanya Lemieux, Natural Resources Canada: page 9 (bottom -

And Peary Caribou (Rangifer Tarandus Pearyi) on Prince of Wales and Somerset Islands, August 2016 Morgan L

Distribution and abundance of muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) and Peary caribou (Rangifer tarandus pearyi) on Prince of Wales and Somerset Islands, August 2016 Morgan L. Anderson ᒧᐊᒐᓐ ᐋᓐᑐᕐᓴᓐ Department of Environment, Government of Nunavut, Igloolik, NU, [email protected] 867-934-2175 ᓂᕐᔪᑎᓂᒃ ᖃᐅᔨᓴᖅᑎ ᖁᑦᑎᒃᑐᒥ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᒥ, ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ ᐆᒪᔪᕐᓂᒃ ᖃᐅᔨᓴᖅᑎᒃᑯᑦ, ᓄᓇᕗᒻ ᒐᕙᒪᒃᑯᖏᑦ ᑎᑎᖅᑲᒃᑯᕕᐊ 209 ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒃ ᓄᓇᕗᑦ X0A 0L0 INTRODUCTION RESULTS MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS • Peary caribou and muskoxen are the only ungulates inhabiting the Muskoxen have declined slightly but remain at high Queen Elizabeth Islands. • Both are important sources of country food and cultural persistence densities. for local communities. Resolute , Taloyoak, and sometimes Gjoa Haven • The muskox population has declined since the 1990s, but it is still • The survey provided a population estimate of 3,052± SE 440 muskoxen harvest from Prince of Wales and Somerset islands. at high density and could support more harvest than is currently on Prince of Wales and Somerset islands (including smaller satellite • Severe winter weather (ground-fast ice ) restricts access to forage and taken, although there is no Total Allowable Harvest (TAH) on MX- islands), with 1,569 ± SE 267 on Prince of Wales, Pandora, Prescott, and causes sporadic die-off events.1, 2, 3 06. Russell islands, and 1,483 ± SE 349 muskoxen on Somerset Island. • The islands were previously occupied by 5,000 Peary caribou, which • Current muskox harvest does not fill the previous TAH (20 tags • The previous survey in 2004 estimated 2,086 muskoxen on Prince of allocated to Resolute, removed in fall 2015) annually for MX-06.15 migrated between Prince of Wales, Somerset, and smaller satellite Wales/Russell islands (1,582-2,746, 95% CI) and 1,910 muskoxen on 4 5 • The drastic decline in Baffin Island caribou over recent years has islands, and the Boothia Peninsula, but the population crashed to Somerset Island (962-3,792 95% CI) very low levels in the 1980s 6, 7and had not recovered as of the most limited harvest opportunities on Baffin Island. -

Movements and Habitat Use of Muskoxen on Bathurst, Cornwallis

MOVEMENTS AND HABITAT USE OF MUSKOXEN (Ovibos moschatus) ON BATHURST, CORNWALLIS, AND DEVON ISLANDS, 2003-2006 Morgan Anderson1 and Michael A. D. Ferguson Version: 23 December 2016 1Department of Environment, Government of Nunavut, Box 209 Igloolik NU X0A 0L0 STATUS REPORT 2016-08 NUNAVUT DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT WILDLIFE RESEARCH SECTION IGLOOLIK, NU i Summary Eleven muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) were fitted with satellite collars in summer 2003 to investigate habitat preferences and movement parameters in areas where they are sympatric with Peary caribou on Bathurst, Cornwallis, and Devon islands. Collars collected locations every 4 days until May 2006, with 4 muskoxen on Bathurst Island collared, 2 muskoxen collared on Cornwallis Island, and 5 muskoxen collared on western Devon Island. Only 5-29% of the satellite locations were associated with an estimated error of less than 150 m (Argos Class 3 locations). Muskoxen in this study used low-lying valleys and coastal areas with abundant vegetation on all 3 islands, in agreement with previous studies in other areas and Inuit qaujimajatuqangit. They often selected tussock graminoid tundra, moist/dry non-tussock graminoid/dwarf shrub tundra, wet sedge, and sparsely vegetated till/colluvium sites. Minimum convex polygon home ranges representing 100% of the locations with <150 m error include these movements between core areas, and ranged from 233 km2 to 2494 km2 for all collared muskoxen over the 3 years, but these home ranges include large areas of unused habitat separating discrete patches of good habitat where most locations were clustered. Several home ranges overlapped, which is not surprising, since muskoxen are not territorial. -

Page 1 So Gr Renandode Onlagrenje Sopssjc Sprapb0496 #125472 One

ᓄᓇᕘᒥ ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ ᑲᑎᒪᔨᖏᑦᑎᒍᑦ ᑐᒃᓯᖅᑑᑦ ᕿᒥᕐᕈᔭᒃᓴᖅ #125472 One Ocean Expeditions - Arctic 2019 cruise season ᑐᒃᓯᖅᑑᑕᐅᔪᖅ New ᖃᓄᐃᑦᑑᓂᖓ: ᐱᓕᕆᐊᕆᔭᐅᔪᒪᔫᑉ ᐳᓚᕋᖅᑐᓕᕆᓂᖅ ᖃᓄᐃᑦᑑᓂᖓ: ᐅᓪᓗᖓ 5/30/2019 5:47:04 PM ᑐᒃᓯᖅᑑᑎᓕᐊᕕᓂᐅᑉ: Period of operation: from 0001-01-01 to 0001-01-01 ᑲᔪᓯᒃᑲᐃᔨᐅᓂᐊᕋᓱᒋᔭᐅᔪᑦ: from 0001-01-01 to 0001-01-01 ᐱᓕᕆᐊᖃᕈᒪᔪᖅ: Aaron Lawton One Ocean Expeditions 38141 2nd Ave Squamish British Columbia V8B 0A6 Canada ᐅᖄᓚᐅᑏᑦ: 6043904900, ᓱᑲᔪᒃᑯᑦ: ᑐᓴᐅᒪᔭᒃᓴᑦ ᖃᓄᐃᑦᑑᑎᓂᒃ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᖃᕐᓂᐊᕆᐊᖓᓐᓂᒃ ᖃᓪᓗᓈᑎᑐᑦ: Expedition cruise tourism in the Canadian Arctic with a maximum of 146 passengers and 25 staff from around the world. We plan to operate 5 voyages in Nunavut on the RCGS Resolute from July 2019 through to September 2019. Ship visits are concentrated in ice- free zones and in arctic communities. Visits ashore last generally no longer than three hours.Our ship, the RCGS Resolute will drift or drop anchor while passengers disembark into small inflatable zodiacs. Passengers will cruise in zodiacs or will land on shore where appropriate. ᐅᐃᕖᑎᑐᑦ: Description du Projet :Nos opérons un vaisseau de tourisme style expédition capable de transporter un maximum de 146 passagers et 25 employés que nous employons de partout dans le monde. Nous planifions opérer 5 voyages dans le Nunavut en 2019 abord le RCGS Resolute à partir du mois de juillets jusqu’au mois de septembre. Les visites à bateau sont concentrées dans les zones d’eau libre ou se trouve la plupart des communautés de L’arctique. Nos visites ne durent pas plus que trois heures. ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᑦ: ᐱᓕᕆᐊᒃᓴᐃᑦ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᖏᑦ:ᐅᒥᐊᕐᔪᐊᒃᑯ ᐳᓚᕋᑦᑐᓕᕆᓂ ᑲᓇᑕᐅᑉ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑑ ᐃᒪᖓᓂ ᐳᓚᕋᑎᓂ ᓂᕆᐅᒋᔭᐅᔪ 146 ᐊᑭᓖᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐳᓚᕋᑏᑦ 25ᓂ ᐳᓚᕋᑐᓕᕆᔨᓂ ᐃᖃᓇᐃᔭᖅᑎᖃᕋᔭᖅᑐᑦ ᓄᓇᕐᔪᐊᒥᖓᕈᓘᔭᕋᔭᖅᐳᑦ.