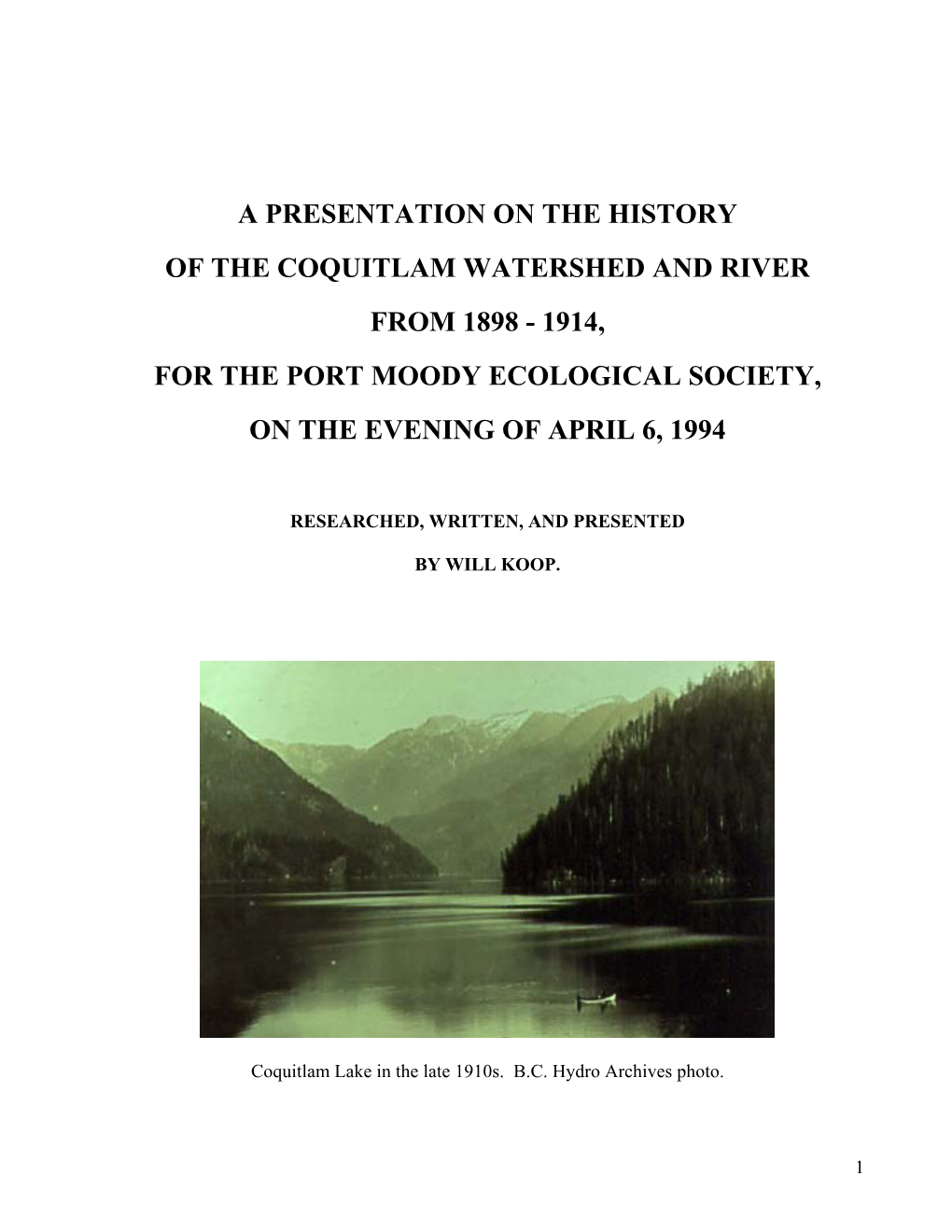

Coquitlam Watershed History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIG TUNNEL IS FINISHED at LAST Researched By: Ralph Drew, Belcarra, BC, August 2013

BIG TUNNEL IS FINISHED AT LAST Researched By: Ralph Drew, Belcarra, BC, August 2013. Source: Vancouver Province, April 27th, 1905. Drill pierced the wall of rock. Rejoicing at Lake Beautiful [Buntzen Lake] to-day when crews working on Vancouver Power Company’s scheme met under centre of mountain — Facts concerning the Great Work. The Vancouver Power Company’s tunnel is finished. The practical completion of this extensive work took place this morning when a ten-foot drill pierced a hole through the last intervening section of rock in the two-and-a-half-mile bore, which will connect Lakes Coquitlam and Beautiful [Buntzen Lake] for the generation of electrical energy. After two and a quarter years of incessant work, involving an expenditure of $320,000, the drill broke through this morning from the Lake Coquitlam end, and leaving but 10 feet of rock remaining, which will be removed by this evening. This marks an important step in the development of the Hydro Electric Power Scheme which is ultimately intended to develop 30,000 horsepower for distribution in Vancouver, New Westminster and Steveston. The big tunnel forms a silent, but eloquent testimonial for the triumph of modern engineering, for, after working from both portals beneath a mountain four thousand feet high for over two years the two ends of the bore met exactly true. Amid cheers of surprise and delight the workmen employed at the Lake Beautiful heading of the tunnel being driven for the Vancouver Power Co., saw the end of a steel frill break through the wall of rock on which they were engaged at 7 o’clock this morning. -

HOW to BENEFIT As a Member Or Seasons Pass Holder at One of Vancouver’S Must See Attractions You Are Eligible for Savings and Benefits at Other Top Attractions

HOW TO BENEFIT As a Member or Seasons Pass holder at one of Vancouver’s Must See Attractions you are eligible for savings and benefits at other top Attractions. Simply present your valid membership or pass at participating Attractions’ guest services, retail outlet or when you make a reservation to enjoy a benefit. There is no limit to the number of times you may present your valid membership or seasons pass. Capilano Suspension Bridge Park featuring the iconic Suspension Bridge, Treetops Adventure, 7 suspended footbridges offering views 100 feet above the forest floor and the Cliffwalk, a labyrinth-like series of narrow cantilevered bridges, stairs and platforms high above the Capilano River offers you 20% off Food and Beverage, (excluding alcohol) at any of our Food & Beverage venues within the park excluding the Cliff House Restaurant and Trading Post gift store. 604.985.7474 capbridge.com Step aboard an old-fashioned horse-drawn vehicle for a Stanley Park Horse-Drawn Tour and meander in comfort through the natural beauty of Stanley Park, Vancouver’s thousand acre wonderland. Three great offers available for members: A) Enjoy a 2 for 1 offer ($42 value) for our regularly-scheduled Stanley Park Horse-Drawn Tours; B) $50 off of a Private Carriage Reservation within Stanley Park and the downtown core of Vancouver, or C) $100 off a Private Carriage Reservation taking place outside of Stanley Park and the downtown core of Vancouver. Restrictions: Must be within our regular operating season of March 1 – December 22. Private carriage bookings must be made in advance. 604.681.5115 stanleypark.com Sea otters, sea lions, snakes and sloths…plus 60,000 other aquatic creatures, await your arrival at the Vancouver Aquarium, conveniently located in Stanley Park. -

The Story of the Coquitlam River Watershed Past, Present and Future

Fraser Salmon and Watersheds Program – Living Rivers Project Coquitlam River Stakeholder Engagement Phase I The Story of the Coquitlam River Watershed Past, Present and Future Prepared for: The City of Coquitlam and Kwikwetlem First Nation Funding provided by: The Pacific Salmon Foundation Additional funding provided by Fisheries and Oceans Canada Prepared by: Jahlie Houghton, JR Environmental – April 2008 Updated by: Coquitlam River Watershed Work Group – October 2008 Final Report: October 24, 2008 2 File #: 13-6410-01/000/2008-1 Doc #: 692852.v1B Acknowledgements I would like to offer a special thanks to individuals of the community who took the time to meet with me, who not only helped to educate me on historical issues and events in the watershed, but also provided suggestions to their vision of what a successful watershed coordinator could contribute in the future. These people include Elaine Golds, Niall Williams, Don Gillespie, Dianne Ramage, Tony Matahlija, Tim Tyler, John Jakse, Vance Reach, Sherry Carroll, Fin Donnelly, Maurice Coulter-Boisvert, Matt Foy, Derek Bonin, Charlotte Bemister, Dave Hunter, Jim Allard, Tom Vanichuk, and George Turi. I would also like to thank members of the City of Coquitlam, Kwikwetlem First Nation, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and Watershed Watch Salmon Society (representative for Kwikwetlem) who made this initiative possible and from whom advice was sought throughout this process. These include Jennifer Wilkie, Dave Palidwor, Mike Carver, Margaret Birch, Hagen Hohndorf, Melony Burton, Tom Cadieux, Dr. Craig Orr, George Chaffee, and Glen Joe. Thank you to the City of Coquitlam also for their printing and computer support services. -

New Product Guide Spring Edition 2019

New Product Guide Spring Edition 2019 Harbour Air | Whistler Air Hotel Belmont Landsea Tours and Adventures ACCOMMODATION TRANSPORTATION AND SIGHTSEEING HOTEL BELMONT HARBOUR AIR | WHISTLER AIR Opening May 2019, with 82 fully renovated rooms, guests will Now offering daily seasonal flights (May - September) from South embrace being in the heart of Downtown Vancouver and pay Terminal YVR to Whistler. This new route allows easy access for homage to its historic lights and legendary nights. This boutique YVR passengers to transfer directly to a mid-day scheduled flight hotel is set to attract a mindset more than an age demographic, to Whistler. Complimentary shuttle service is available between offering superior guest service and attention to detail while Main and South Terminals. This convenient new route will appeal driving culturally inspired, fun, and insider experiences to the to both those arriving or departing YVR, as well as those travellers Granville Street Entertainment District. hotelbelmont.ca staying outside of the downtown Vancouver core. harbourair.com LANDIS HOTEL & SUITES LANDSEA TOURS AND ADVENTURES The recently completed $2 million renovation includes convenient Launching on May 1, the Hop On, Hop Off City Tour operates on features designed for comfort and ease. A suites-only hotel in modern double-decker buses, with the upper levels featuring a the heart of Vancouver’s downtown core, the accommodations glass skylight to allow for natural light and spectacular views of are spacious and condo-inspired, each featuring stunning views, the city. Tickets are purchased for a specific tour date year-round, a fully-equipped kitchen, two generous bedrooms and separate with pickups every 30-40 minutes on a 2-hour & 15-minute tour living and dining spaces. -

Appendix B: Hydrotechnical Assessment

Sheep Paddocks Trail Alignment Analysis APPENDIX B: HYDROTECHNICAL ASSESSMENT LEES+Associates -112- 30 Gostick Place | North Vancouver, BC V7M 3G3 | 604.980.6011 | www.nhcweb.com 300217 15 August 2013 Lees + Associates Landscape Architects #509 – 318 Homer Street Vancouver, BC V6B 2V2 Attention: Nalon Smith Dear Mr. Smith: Subject: Sheep Paddocks Trail Alignment – Phase 1 Hydrotechnical Assessment Preliminary Report 1 INTRODUCTION Metro Vancouver wishes to upgrade the Sheep Paddocks Trail between Pitt River Road and Mundy Creek in Colony Farm Regional Park on the west side of the Coquitlam River. The trail is to accommodate pedestrian and bicycle traffic and be built to withstand at least a 1 in 10 year flood. The project will be completed in three phases: 1. Phase 1 – Route Selection 2. Phase 2 – Detailed Design 3. Phase 3 – Construction and Post-Construction This letter report provides hydrotechnical input for Phase 1 – Route Selection. Currently, a narrow footpath runs along the top of a berm on the right bank of the river. The trail suffered erosion damage in 2007 and was subsequently closed to the public but is still unofficially in use. Potential future routes include both an inland and river option, as well as combinations of the two. To investigate the feasibility of the different options and help identify the most appropriate trail alignment from a hydrotechnical perspective, NHC was retained to undertake the following Phase I scope of work: • Participate in three meetings. • Attend a site visit. • Estimate different return period river flows and comment on local drainage requirements. • Simulate flood levels and velocities corresponding to the different flows. -

BC Hydro Dam Safety Quarterly Report

Confidential - Discussion/Information Board briefing – DAM SAFETY QUARTERLY REPORT Executive Summary The purpose of this report is to update the Capital Projects Committee of the Board of Directors on key dam risk management activities during the period from April 1, 2019 to June 30, 2019, and to provide reasonable assurance that the safety of dams operated by BC Hydro continues to be managed to the established guidelines and criteria of the Dam Safety Program. The Dam Safety Program has been executed in a manner that is consistent with its stated objectives throughout the reporting period. The overall Dam Safety risk profile is shown in Figure 1. There have been no changes in assessed risk this quarter. Risk Profile of BC Hydro’s Dam Dam Safety Contribution to Enterprise Risk Dam Safety is assigned a high “risk priority” within BC Hydro’s Enterprise Risk report, as depicted below. This high rating is arrived at by recognizing that: (1) there can be extremely severe consequences from the failure of a dam; (2) a dam failure can progress quickly without leaving adequate time to take effective actions to reverse the failure; and (3) our ability to mitigate this risk is considered to be “moderate” given that upgrades to existing dams are typically expensive, time and resource intensive and frequently technically challenging. The nature of dam safety risk is that it can only be realistically managed by minimizing to the extent practicable the probability of occurrence through a well-constructed and well-executed Dam Safety Program. Speed Ability F19 Q4 Change from Risk Severity of to Risk Last Quarter Onset Mitigate Priority Likelihood Dam Safety For F20 Q1 the overall H L Fast M H Dam Safety risk is Risk of a dam safety incident stable. -

Port Coquitlam Flood Mapping Update

Port Coquitlam Flood Mapping Update RECOMMENDATION: None. PREVIOUS COUNCIL/COMMITTEE ACTION On September 17, 2019 Council carried the following motion: That staff prepare flood maps showing current flood risk to Port Coquitlam from the Fraser Basin and provide a report in the fall 2019 with information about the risks facing the community from rising sea levels that align with projections in the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report. REPORT SUMMARY Port Coquitlam has participated in the Fraser Basin Council’s Lower Mainland Flood Management Strategy (“the Strategy”) since its development in 2014. Participants in the strategy have responsibilities or interests related to flood management and include the Government of Canada, the Province of British Columbia, Lower Mainland local governments, First Nations and non- governmental and private sector entities in the region. This report summarizes the flood projections for Port Coquitlam, the regional work completed to date and presents the Strategy’s next phase. BACKGROUND The Lower Fraser Watershed is fed by 12 major watersheds. 1. The Upper / Middle Fraser 7. Chilcotin 2. Stuart 8. North Thompson 3. McGregor 9. South Thompson 4. Nechako 10. Thompson 5. Quesnel 11. Lillooet 6. West Road-Blackwater 12. Harrison These watersheds are illustrated on Figure 1. Report To: Committee of Council Department: Engineering & Public Works Approved by: F. Smith Meeting Date: November 19, 2019 Port Coquitlam Flood Mapping Update Figure 1 – Fraser Basin Watersheds https://www.fraserbasin.bc.ca/basin_watersheds.html In addition, the Lower Fraser watershed incorporates a number of smaller watersheds: Stave Lake and River drain into the Fraser between Maple Ridge and Mission; Alouette Lake and River flow into the Pitt River; the Pitt River drains south from Garibaldi Provincial Park through Pitt Lake, emptying into the Fraser River between Pitt Meadows and Port Coquitlam. -

Revised Draft Experiences with Inter Basin Water

REVISED DRAFT EXPERIENCES WITH INTER BASIN WATER TRANSFERS FOR IRRIGATION, DRAINAGE AND FLOOD MANAGEMENT ICID TASK FORCE ON INTER BASIN WATER TRANSFERS Edited by Jancy Vijayan and Bart Schultz August 2007 International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID) 48 Nyaya Marg, Chanakyapuri New Delhi 110 021 INDIA Tel: (91-11) 26116837; 26115679; 24679532; Fax: (91-11) 26115962 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.icid.org 1 Foreword FOREWORD Inter Basin Water Transfers (IBWT) are in operation at a quite substantial scale, especially in several developed and emerging countries. In these countries and to a certain extent in some least developed countries there is a substantial interest to develop new IBWTs. IBWTs are being applied or developed not only for irrigated agriculture and hydropower, but also for municipal and industrial water supply, flood management, flow augmentation (increasing flow within a certain river reach or canal for a certain purpose), and in a few cases for navigation, mining, recreation, drainage, wildlife, pollution control, log transport, or estuary improvement. Debates on the pros and cons of such transfers are on going at National and International level. New ideas and concepts on the viabilities and constraints of IBWTs are being presented and deliberated in various fora. In light of this the Central Office of the International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID) has attempted a compilation covering the existing and proposed IBWT schemes all over the world, to the extent of data availability. The first version of the compilation was presented on the occasion of the 54th International Executive Council Meeting of ICID in Montpellier, France, 14 - 19 September 2003. -

Reduced Annualreport1972.Pdf

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF RECREATION AND CONSERVATION HON. ROBERT A. WILLIAMS, Minister LLOYD BROOKS, Deputy Minister REPORT OF THE Department of Recreation and Conservation containing the reports of the GENERAL ADMINISTRATION, FISH AND WILDLIFE BRANCH, PROVINCIAL PARKS BRANCH, BRITISH COLUMBIA PROVINCIAL MUSEUM, AND COMMERCIAL FISHERIES BRANCH Year Ended December 31 1972 Printed by K. M. MACDONALD, Printer to tbe Queen's Most Excellent Majesty in right of the Province of British Columbia. 1973 \ VICTORIA, B.C., February, 1973 To Colonel the Honourable JOHN R. NICHOLSON, P.C., O.B.E., Q.C., LLD., Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: Herewith I beg respectfully to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Recreation and Conservation for the year ended December 31, 1972. ROBERT A. WILLIAMS Minister of Recreation and Conservation 1_) VICTORIA, B.C., February, 1973 The Honourable Robert A. Williams, Minister of Recreation and Conservation. SIR: I have the honour to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Recreation and Conservation for the year ended December 31, 1972. LLOYD BROOKS Deputy Minister of Recreation and Conservation CONTENTS PAGE Introduction by the Deputy Minister of Recreation and Conservation_____________ 7 General Administration_________________________________________________ __ ___________ _____ 9 Fish and Wildlife Branch____________ ___________________ ________________________ _____________________ 13 Provincial Parks Branch________ ______________________________________________ -

Building of the Coquitlam River and Port Moody Trails Researched and Written by Ralph Drew, Belcarra, BC, June 2010; Updated Dec 2012 and Dec 2013

Early Trail Building in the New Colony of British Columbia — John Hall’s Building of the Coquitlam River and Port Moody Trails Researched and written by Ralph Drew, Belcarra, BC, June 2010; updated Dec 2012 and Dec 2013. A recent “find” of colonial correspondence in the British Columbia Archives tells a story about the construction of the Coquitlam River and Port Moody Trails between 1862 and 1864 by pioneer settler John Hall. (In 1870 Hall pre-empted 160 acres of Crown Land on Indian Arm and became Belcarra’s first European settler.) The correspondence involves a veritable “who’s who” of people in the administration in the young ‘Colony of British Columbia’. This historic account serves to highlight one of the many challenges faced by our pioneers during the period of colonial settlement in British Columbia. Sir James Douglas When the Fraser River Gold Rush began in the spring of 1858, there were only about 250 to 300 Europeans living in the Fraser Valley. The gold rush brought on the order of 30,000 miners flocking to the area in the quest for riches, many of whom came north from the California gold fields. As a result, the British Colonial office declared a new Crown colony on the mainland called ‘British Columbia’ and appointed Sir James Douglas as the first Governor. (1) The colony was first proclaimed at Fort Langley on 19th November, 1858, but in early 1859 the capital was moved to the planned settlement called ‘New Westminster’, Sir James Douglas strategically located on the northern banks of the Fraser River. -

Rivers at Risk: the Status of Environmental Flows in Canada

Rivers at Risk: The Status of Environmental Flows in Canada Prepared by: Becky Swainson, MA Research Consultant Prepared for: WWF-Canada Freshwater Program Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of the river advocates and professionals from across Canada who lent their time and insights to this assessment. Also, special thanks to Brian Richter, Oliver Brandes, Tim Morris, David Schindler, Tom Le Quesne and Allan Locke for their thoughtful reviews. i Rivers at Risk Acronyms BC British Columbia CBM Coalbed methane CEMA Cumulative Effects Management Association COSEWIC Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada CRI Canadian Rivers Institute DFO Fisheries and Oceans Canada EBF Ecosystem base flow IBA Important Bird Area IFN Instream flow needs IJC International Joint Commission IPP Independent Power Producer GRCA Grand River Conservation Authority LWR Low Water Response MOE Ministry of Environment (Ontario) MNR Ministry of Natural Resources (Ontario) MRBB Mackenzie River Basin Board MW Megawatt NB New Brunswick NGO Non-governmental organization NWT Northwest Territories P2FC Phase 2 Framework Committee PTTW Permit to Take Water QC Quebec RAP Remedial Action Plan SSRB South Saskatchewan River Basin UNESCO United Nations Environmental, Scientific and Cultural Organization US United States WCO Water Conservation Objectives ii Rivers at Risk Contents Rivers at Risk: The Status of Environmental Flows in Canada CONTENTS Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... -

George Black — Early Pioneer Settler on the Coquitlam River

George Black — Early Pioneer Settler on the Coquitlam River Researched and written by Ralph Drew, Belcarra, BC, December 2018. The ‘Colony of British Columbia’ was proclaimed at Fort Langley on November 19th,1858. In early 1859, Colonel Richard Clement Moody, RE, selected the site for the capital of the colony on the north side of the Fraser River where the river branches. The Royal Engineers established their camp at ‘Sapperton’ and proceeded to layout the future townsite of ‘Queensborough’ (later ‘New Westminster’). On July 17th, 1860, ‘New Westminster’ incorporated to become the first municipality in Western Canada. During the winter of 1858–59, the Fraser River froze over for several months and Colonel Moody realized his position when neither supply boat nor gun-boat could come to his aid in case of an attack. As a consequence, Colonel Moody built a “road” to Burrard Inlet in the summer of 1859 as a military expediency, in order that ships might be accessible via salt water. The “road” was initially just a pack trail that was built due north from ‘Sapperton’ in a straight line to Burrard Inlet. In 1861, the pack trail was upgraded to a wagon road ― known today as ‘North Road’. (1) The ‘Pitt River Road’ from New Westminster to ‘Pitt River Meadows’ was completed in June 1862. (2) In the summer of 1859, (3)(4) the first European family to settle in the Coquitlam area arrived on the schooner ‘Rob Roy’ on the west side of the Pitt River to the area known as ‘Pitt River Meadows’ (today ‘Port Coquitlam’) — Alexander McLean (1809–1889), his wife (Jane), and their two small boys: Alexander (1851–1932) and Donald (1856–1930).