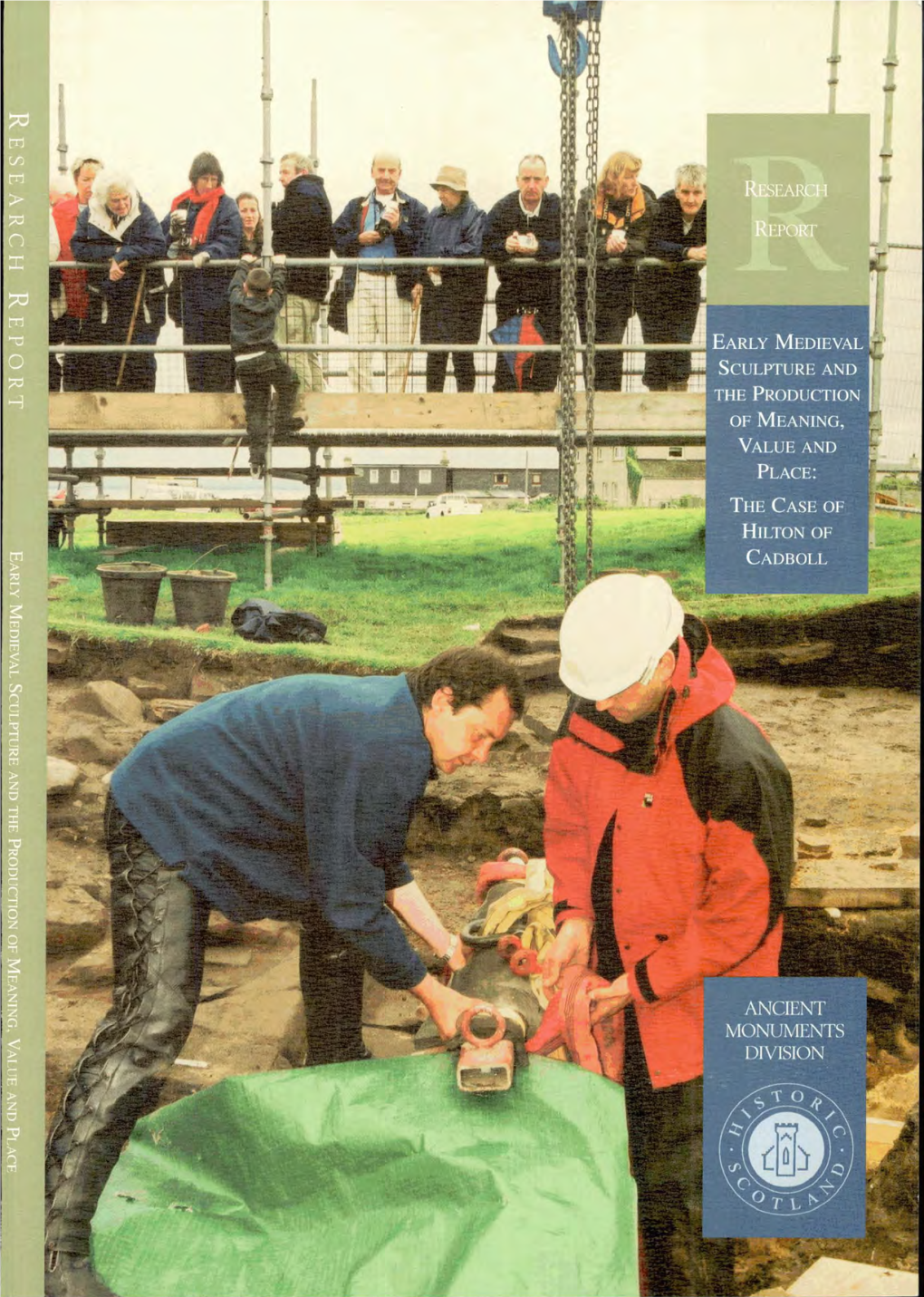

The Case of Hilton Cadboll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eprints.Whiterose.Ac.Uk/10449

This is a repository copy of Early Scottish Monasteries and Prehistory: A Preliminary Dialogue. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10449/ Article: Carver, Martin orcid.org/0000-0002-7981-5741 (2009) Early Scottish Monasteries and Prehistory: A Preliminary Dialogue. The Scottish Historical Review. pp. 332-351. ISSN 0036-9241 https://doi.org/10.3366/E0036924109000894 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ This is an author produced version of a paper published in the SCOTTISH HISTORICAL REVIEW White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10449 Published paper Carver, M (2009) Early Scottish Monasteries and Prehistory: A Preliminary Dialogue SCOTTISH HISTORICAL REVIEW 88 (226) 332-351 http://doi.org/10.3366/E0036924109000894 White Rose Research Online [email protected] Early Scottish Monasteries and prehistory: a preliminary dialogue Martin Carver1 Reflecting on the diversity of monastic attributes found in the east and west of Britain, the author proposes that pre-existing ritual practice was influential, even determinant. -

Autumn Trip to Inverness 2017

Autumn trip to Inverness 2017 Brian weaving his magic spell at Clava Cairns © Derek Leak Brian Ayers spends part of his year in the north low buttress with a recumbent stone in the SE. of Scotland and offered to show us the area The three Clava cairns cross a field near round Inverness. Amazing geology and scenery, Culloden Moor. These are late Neolithic/Bronze intriguing stone circles, carved Pictish crosses, Age and two circles have outliers like spokes with snatches of Scottish history involving on a wheel ending in a tall upright. One circle ambitious Scottish lords, interfering kings is heaped with stones and revetted, with the of England, Robert the Bruce, and rebellious very centre stone-free. Another is completely Jacobites added to the mix. Scotland’s history covered in stones while the most northerly was long a rivalry between the Highlands and circle has walls surviving to shoulder height Isles, and the Lowlands; the ancient Picts, and and the tunnel entrance probably once roofed. the Scots (from Ireland), and the French. Cup-marked stones mark the entrance to the In the shadow of Bennachie, a large darkest space. mountain, is Easter Aquhorthies stone circle. Standing on the south bank of a now-drained A well preserved recumbent stone circle, sea loch with RAF Lossiemouth to the north, is designated by the huge stone lying on its side the impressive Spynie Palace. For much of its flanked by two upright stones which always early years the bishopric was peripatetic before face SSW, it apparently formed a closed door the Pope allowed the move to Spynie in 1206. -

{PDF EPUB} the Pictish Symbol Stones of Scotland by Iain Fraser ISBN 13: 9781902419534

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Pictish Symbol Stones of Scotland by Iain Fraser ISBN 13: 9781902419534. This is a revised and expanded version of the RCAHMS publication originally entitled Pictish Symbol Stones - a Handlist . It publishes the complete known corpus of Pictish symbol stones, including descriptions, photos and professional archaeological drawings of each. An introduction gives an overview of work on the stones, and analyses the latest thinking as to their function and meaning. "synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title. After twenty years working in the shipping industry in Asia and America, Iain Fraser returned home in 1994 to establish The Elephant House, a caf�-restaurant in the Old Town famed for its connection with a certain fictional boy wizard. The Pictish Symbolic Stones of Scotland. This is a revised and expanded version of the RCAHMS publication originally entitled Pictish Symbol Stones - a Handlist . It publishes the complete known corpus of Pictish symbol stones, including descriptions, photos and professional archaeological drawings of each. Read More. This is a revised and expanded version of the RCAHMS publication originally entitled Pictish Symbol Stones - a Handlist . It publishes the complete known corpus of Pictish symbol stones, including descriptions, photos and professional archaeological drawings of each. Read Less. Dyce Symbol Stones. Wonder at the mysterious carvings on a pair of Pictish stones, one featuring a rare ogham inscription . The Dyce symbol stones are on display in an enclosure at the ruined kirk of St Fergus in Dyce. The older of the two, probably dating from about AD 600, is a granite symbol stone depicting a swimming beast above a cluster of symbols. -

A Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N. Billings University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, European History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Billings, Traci N., "Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1351. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1351 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold, PhD. The interpretation of prehistoric iconography is complicated by the tendency to project contemporary male/female gender dichotomies into the past. Pictish monumental stone sculpture in Scotland has been studied over the last 100 years. Traditionally, mirror and comb symbols found on some stones produced in Scotland between AD 400 and AD 900 have been interpreted as being associated exclusively with women and/or the female gender. This thesis re-examines this assumption in light of more recent work to offer a new interpretation of Pictish mirror and comb symbols and to suggest a larger context for their possible meaning. -

Wester Rarichie Hill, Tain, Ross-Shire

Wester Rarichie Hill, Tain, Ross-shire Wester Rarichie Hill The contiguous, picturesque Seaboard Villages of Tain, Ross-shire Hilton, Balintore and Shandwick to the northeast of Wester Rarichie Hill feature a pier, harbour A rare opportunity to purchase a block of and bay. Balintore offers a shop, post office and hill ground overlooking the moray firth. pharmacy. The closest town of Tain, Scotland’s oldest burgh, provides further services. The hill (currently forming part of a larger Tain 8 miles, Inverness 34 miles, agricultural holding, Wester Rarichie Farm) is Inverness Airport 41 miles, Edinburgh 188 miles accessed via a private track from a minor road Wester Rarichie Hill (About 726 acres) connecting the Seaboard Villages to the B9175. • Enclosed hill ground varying between 80 The A9 provides transport links north and south, and 200 metres above sea level. and allows easy access to Inverness, the capital of the Highlands. Inverness airport provides regular • Cattle shelter of modern construction. flights throughout the UK and to Europe. The local • Potential for afforestation on the hill, subject railway station at Fearn provides services along to Forestry Commission consent. the ‘Far North Line’. A sleeper service operates from Inverness railway station to London. • Spectacular 360-degree views. • Expansive coastline measuring The Land approximately 1,600 metres. Wester Rarichie Hill extends to approximately 726 acres of land, including a modern farm building. • No recent sporting records but scope for rough shooting and roe deer stalking. The highest summit within the subjects peaks at 200 metres above sea level and offers a About 726 acres (294 ha) in total. -

The Declining Pictish Symbol - a Reappraisal the Late Gordon Murray

Proc SocAntiq Scot, (1986)6 11 , 223-253 The declining Pictish symbol - a reappraisal The late Gordon Murray SUMMARY The paper is mainly concerned with the three commonest Pictish symbols, the crescent, the double disc with Pictish the Z-rod and 'elephant' 'beast'.BStevensonR or K ideasDr The of and Dr I Henderson are outlined, namely that for each of these symbols a stylistic 'declining sequence' can be traced that corresponds approximately to a chronological sequence, enabling the probable place of origin of the symbol to be determined. The forms and distributions of the three symbols are examined in detail and it is argued that the finer examples of each are centred in different areas. For reasons which are stated, the classification of the crescent differs here from that made by Stevenson. The different decorative forms show significantly different distributions originthe but appears be to north. far most The the typicalin examples Z-rodthe of accompanying doublethe discfoundare predominantly in Aberdeenshire, where it is suggested that the symbol may have originated. Examples Pictishthe of beast hereare graded according extentthe to that their features correspond otherwiseor with lista whatof 'classical' the appear be to features form. distributionofthe The and general quality existingof examples suggest that originthe centre thisof symbol probablyis the in area Angusof easternand Perthshire. The paper also discusses arrangementthe symbolsthe of statements, in with some tentative remarks on the relative chronology of the mirror appearing alone as a qualifier. INTRODUCTION principle Th e declininth f eo g symbo thas i l t there existe prototypda r 'correcteo ' forr mfo at least some of the Pictish symbols, to which all surviving instances approximate in varying degrees, but from which later examples tend to depart more than earlier ones. -

'They Made It a Living Thing Didn't They ….': the Growth

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository The final, definitive version of this paper has been published in A Future for Archaeology, Robert Layton and Stephen Shennan eds, UCL Press/Left Coast Press, 2006, pp. 107-126. The final version is available at http://www.lcoastpress.com/book.php?id=57 ‘THEY MADE IT A LIVING THING DIDN’T THEY ….’: THE GROWTH OF THINGS AND THE FOSSILIZATION OF HERITAGE. Siân Jones Christine: […] I think everything has feelings. Even a piece of stone that was carved all those years ago. I feel that it's, well they made it a living thing didn't they? Siân: Mmmm Christine: When they did that. Siân: Yes, when they created it? Christine: Yes. They made a living thing. So I feel, yes, I think when it goes back into the ground it will be home. Siân: Yes, that's really interesting. Christine laughs. Christine: I do, I feel it's waiting to go back. We've taken it out, disturbed it, we've looked at it and it, I mean I know it has to have lots of things done to it to preserve it erm, but I think once it goes back I feel it'll shine in its own … Siân: In its place? Christine: Yes. And I hope it goes back where it was found. Because I feel that that's right.1 The piece of stone at the heart of this conversation is the long-lost lower section of a famous Pictish sculpture dating from around AD 800 (Figure 1). -

School Handbook Hilton of Cadboll Primary School 2021 -2022

‘Aiming to get it right for all learners’ School Handbook Hilton of Cadboll Primary School 2021 -2022 Hilton of Cadboll Primary School Hilton By Fearn IV20 1XR Tel: 01862 832272 e-mail: [email protected] School website: www.hiltonofcadboll.edublogs.com Also find us on Facebook and Twitter: @HiltonofCadboll Head Teacher: Mrs R. Rooney Principal Teacher: Mr B. Mackay Section 1 - School Information Vision, Values and Aims Staff Information The School Day Term dates Enrolment Dress Code/Uniform School Meals Attendance/Absence Safety and security/Emergencies Adverse Weather Medical Information Administration of medicine Section 2 – Parental Involvement Involvement Parent Council Parent Partnerships Parent Meetings Reporting to Parents Home Learning Home and School Links School Community Pupil Representation and Involvement Extra-Curricular Activities Behaviour, Conduct and Attitude Bullying Section 3 - Curriculum Curriculum of Excellence Active Learning Planning Curriculum, Assessment and Arrangements for Reporting Learning Journey and Pupil Profiles Standardised Assessments Section 4 – Support for Pupils GIRFEC Wellbeing Named Person Equal Opportunities Additional Support Needs Educational Psychology Service Child Protections Section 5 – School Improvement School Improvement Standards and Quality Report Raising attainment Pupil Equity Funding School Inspections 2 Dear Parent/Carer, I am very pleased to welcome you and your child to Hilton of Cadboll Primary School. We look forward to a long and lasting friendship and partnership with you. The purpose of this brochure is to give you as much information, in an easily digestible form, about our school. It is, however, by no means exhaustive and if you have any queries you feel this booklet fails to cover, do not hesitate to contact me. -

Highland Archaeology Services Ltd

Highland Archaeology Services Ltd Watching Brief 4 Burnside Hilton of Cadboll Ross-shire 7 Duke Street Cromarty Ross-shire IV11 8YH Tel: 01381 600491 Fax: 07075 055074 Mobile: 07834 693378 Email: [email protected] Web: www.hi-arch.co.uk VAT No. 838 7358 80 Registered in Scotland no. 262144 Registered Office: 10 Knockbreck Street, Tain, Ross-shire IV19 1BJ Hilton Burnside (Watching Brief): Report May 2006 Watching Brief: 4 Burnside Hilton of Cadboll Ross-shire Report No. HAS060505 Client WPA Design acting for Mr and Mrs Joy Planning Ref 06/00084/FULRC Author John Wood Date 12 May 2006 © Highland Archaeology Services Ltd and the author 2006. This report may be reproduced and distributed by the client, Highland Council or the RCAHMS only for research and public information purposes without charge provided copyright is acknowledged. Summary An archaeological watching brief was implemented by Highland Archaeology Services Ltd on 27 April 2006 to record the nature and extent of any archaeology likely to be affected by a house extension at 4 Burnside, Hilton of Cadboll, Tain IV20 1XF. No archaeological finds or features were found and no further archaeological work is recommended. 2 Hilton Burnside (Watching Brief): Report May 2006 Contents Summary........................................................................................................................................................................2 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................................3 -

Music in Scotland Before the Mid Ninth Century an Interdisciplinary

Clements, Joanna (2009) Music in Scotland before the mid-ninth century: an interdisciplinary approach. MMus(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2368/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Music in Scotland before the Mid-Ninth Century: An Interdisciplinary Approach Joanna Clements Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MMus, Musicology Department of Music Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow February 2009 Abstract There are few sources for early medieval Scottish music and their interpretation is contentious. Many writers have consequently turned to Irish sources to supplement them. An examination of patterns of cultural influence in sculpture and metalwork suggests that, in addition to an Irish influence, a Northumbrian Anglo-Saxon influence and sources should be considered. Differences in the musical evidence from these groups, however, suggest a complex process of diffusion, innovation and local choice in the interaction of their musical cultures. The difficulty of predicting the course of such a process means that the observation of cultural influence in other disciplines is not on its own a useful tool in the study of music in Scotland before the mid-ninth century. -

Presenting Archaeological Sites to the Public in Scotland

Presenting Archaeological Sites to the Public in Scotland Steven M.Timoney Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Archaeology, University of Glasgow, May 2008 Abstract This thesis is an exploration of the nature of archaeological sites presented to the public in Scotland through an analysis of five case studies. The project utilises qualitative in-depth in interviews, an approach that, although well recognised in other social sciences, has been little-used archaeology. For this project, semi-structured recorded interviews were undertaken with participants at the sites, which were subsequently transcribed and analysed using QSR NVivo software. This approach, the rationales behind using it, and benefits for research in public archaeology, will be discussed in detail. This will be followed by an in- depth analysis of the roles and significances of archaeology, the ways it influences and is influenced by perceptions of the past, and the values placed upon it. The essence of the thesis will then focus on the in-depth analysis of the case studies. Backgrounds will be given to each of the sites, providing a framework from which extracts of interviews will be used to elucidate on themes and ideas of participant discussions. This approach allows for the real, lived experiences of respondents to be relayed, and direct quotations will be used to provide a greater context for discussions. This will reflect a number of recurring themes, which developed during interviews, both within sites and across sites. The interviews will also reflect the individual roles and functions of archaeological sites for the public, and the often idiosyncratic nature of participant engagements with archaeology. -

NIGG & SHANDWICK COMMUNITY COUNCIL GENERAL MEETING At

NIGG & SHANDWICK COMMUNITY COUNCIL GENERAL MEETING at NIGG COMMUNITY HALL - 11th April 2019 MINUTES (DRAFT) Attendees: Peter Grant, Christine Asher, Tony Ross, Helen Campbell, Veronica Morrison, Stuart McLean, Fiona Robertson (Highland Council), Derek Louden (Highland Council) Agenda Minutes Action item 1 Apologies – Alasdair Rhind (Highland Council), Police Scotland 2 Police Report: Police were unable to attend. TR read from a report supplied by Police Sergeant Joanne Thomson. This report is attached at the end of these minutes. 3 Minutes: The minutes from the last meeting on 14th February 2019 were approved. VM proposed; HC seconded. 4 Matters Arising: Response from Global as per previous meeting action to contact them regarding several concerns we had. Below are the points from the response from Rory Gunn at Nigg Energy Park: Throbbing machinery – The description of this noise suggests that it has come from the main generators of the rig or vessels alongside. Unfortunately, it is essential for the vessels and rigs which come to Nigg Energy Park to run their main engines to ensure the safety systems and services are operational. During the still winter nights, this noise can travel some distance, and in the past we have had similar complaints from Cromarty, but unfortunately this is not a noise issue we are able to address directly, and where we have received complaints in the past and taken noise readings, those readings are well below the recommended levels. We are working 24 hrs per day on the rig in the dock at present, and ETD is anticipated to be late March – mid-April.