'They Made It a Living Thing Didn't They ….': the Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eprints.Whiterose.Ac.Uk/10449

This is a repository copy of Early Scottish Monasteries and Prehistory: A Preliminary Dialogue. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10449/ Article: Carver, Martin orcid.org/0000-0002-7981-5741 (2009) Early Scottish Monasteries and Prehistory: A Preliminary Dialogue. The Scottish Historical Review. pp. 332-351. ISSN 0036-9241 https://doi.org/10.3366/E0036924109000894 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ This is an author produced version of a paper published in the SCOTTISH HISTORICAL REVIEW White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10449 Published paper Carver, M (2009) Early Scottish Monasteries and Prehistory: A Preliminary Dialogue SCOTTISH HISTORICAL REVIEW 88 (226) 332-351 http://doi.org/10.3366/E0036924109000894 White Rose Research Online [email protected] Early Scottish Monasteries and prehistory: a preliminary dialogue Martin Carver1 Reflecting on the diversity of monastic attributes found in the east and west of Britain, the author proposes that pre-existing ritual practice was influential, even determinant. -

A Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N. Billings University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, European History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Billings, Traci N., "Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1351. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1351 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold, PhD. The interpretation of prehistoric iconography is complicated by the tendency to project contemporary male/female gender dichotomies into the past. Pictish monumental stone sculpture in Scotland has been studied over the last 100 years. Traditionally, mirror and comb symbols found on some stones produced in Scotland between AD 400 and AD 900 have been interpreted as being associated exclusively with women and/or the female gender. This thesis re-examines this assumption in light of more recent work to offer a new interpretation of Pictish mirror and comb symbols and to suggest a larger context for their possible meaning. -

School Handbook Hilton of Cadboll Primary School 2021 -2022

‘Aiming to get it right for all learners’ School Handbook Hilton of Cadboll Primary School 2021 -2022 Hilton of Cadboll Primary School Hilton By Fearn IV20 1XR Tel: 01862 832272 e-mail: [email protected] School website: www.hiltonofcadboll.edublogs.com Also find us on Facebook and Twitter: @HiltonofCadboll Head Teacher: Mrs R. Rooney Principal Teacher: Mr B. Mackay Section 1 - School Information Vision, Values and Aims Staff Information The School Day Term dates Enrolment Dress Code/Uniform School Meals Attendance/Absence Safety and security/Emergencies Adverse Weather Medical Information Administration of medicine Section 2 – Parental Involvement Involvement Parent Council Parent Partnerships Parent Meetings Reporting to Parents Home Learning Home and School Links School Community Pupil Representation and Involvement Extra-Curricular Activities Behaviour, Conduct and Attitude Bullying Section 3 - Curriculum Curriculum of Excellence Active Learning Planning Curriculum, Assessment and Arrangements for Reporting Learning Journey and Pupil Profiles Standardised Assessments Section 4 – Support for Pupils GIRFEC Wellbeing Named Person Equal Opportunities Additional Support Needs Educational Psychology Service Child Protections Section 5 – School Improvement School Improvement Standards and Quality Report Raising attainment Pupil Equity Funding School Inspections 2 Dear Parent/Carer, I am very pleased to welcome you and your child to Hilton of Cadboll Primary School. We look forward to a long and lasting friendship and partnership with you. The purpose of this brochure is to give you as much information, in an easily digestible form, about our school. It is, however, by no means exhaustive and if you have any queries you feel this booklet fails to cover, do not hesitate to contact me. -

Highland Archaeology Services Ltd

Highland Archaeology Services Ltd Watching Brief 4 Burnside Hilton of Cadboll Ross-shire 7 Duke Street Cromarty Ross-shire IV11 8YH Tel: 01381 600491 Fax: 07075 055074 Mobile: 07834 693378 Email: [email protected] Web: www.hi-arch.co.uk VAT No. 838 7358 80 Registered in Scotland no. 262144 Registered Office: 10 Knockbreck Street, Tain, Ross-shire IV19 1BJ Hilton Burnside (Watching Brief): Report May 2006 Watching Brief: 4 Burnside Hilton of Cadboll Ross-shire Report No. HAS060505 Client WPA Design acting for Mr and Mrs Joy Planning Ref 06/00084/FULRC Author John Wood Date 12 May 2006 © Highland Archaeology Services Ltd and the author 2006. This report may be reproduced and distributed by the client, Highland Council or the RCAHMS only for research and public information purposes without charge provided copyright is acknowledged. Summary An archaeological watching brief was implemented by Highland Archaeology Services Ltd on 27 April 2006 to record the nature and extent of any archaeology likely to be affected by a house extension at 4 Burnside, Hilton of Cadboll, Tain IV20 1XF. No archaeological finds or features were found and no further archaeological work is recommended. 2 Hilton Burnside (Watching Brief): Report May 2006 Contents Summary........................................................................................................................................................................2 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................................3 -

Music in Scotland Before the Mid Ninth Century an Interdisciplinary

Clements, Joanna (2009) Music in Scotland before the mid-ninth century: an interdisciplinary approach. MMus(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2368/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Music in Scotland before the Mid-Ninth Century: An Interdisciplinary Approach Joanna Clements Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MMus, Musicology Department of Music Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow February 2009 Abstract There are few sources for early medieval Scottish music and their interpretation is contentious. Many writers have consequently turned to Irish sources to supplement them. An examination of patterns of cultural influence in sculpture and metalwork suggests that, in addition to an Irish influence, a Northumbrian Anglo-Saxon influence and sources should be considered. Differences in the musical evidence from these groups, however, suggest a complex process of diffusion, innovation and local choice in the interaction of their musical cultures. The difficulty of predicting the course of such a process means that the observation of cultural influence in other disciplines is not on its own a useful tool in the study of music in Scotland before the mid-ninth century. -

Hilton of Cadboll Primary School Nursery Class Tain Integrated

Integrated Inspection by the Care Commission and HM Inspectorate of Education of Hilton of Cadboll Primary School Nursery Class The Highland Council 8 June 2005 Hilton of Cadboll Primary School Nursery Class Hilton Tain Ross-shire IV20 1XE The Regulation of Care (Scotland) Act, 2001, requires that the Care Commission inspect all care services covered by the Act every year to monitor the quality of care provided. In accordance with the Act, the Care Commission and HM Inspectorate of Education carry out integrated inspections of the quality of care and education. In doing this, inspection teams take account of National Care Standards, Early Education and Childcare up to the age of 16, and The Child at the Centre. The following standards and related quality indicators were used in the recent inspection. National Care Standard Child at the Centre Quality Indicator Standard 2 – A Safe Environment Resources Standard 4 – Engaging with Children Development and learning through play Standard 5 – Quality of Experience Curriculum Children’s development and learning Standard 6 – Support and Development Support for children and families Standard 14 – Well-managed Service Management, Leadership and Quality Assurance Evaluations made using HMIE quality indicators use the following scale, and these words are used in the report to describe the team’s judgements: Very good : major strengths Good : strengths outweigh weaknesses Fair : some important weaknesses Unsatisfactory : major weaknesses Reports contain Recommendations which are intended to support improvements in the quality of service. Any Requirements refer to actions which must be taken by service providers to ensure that regulations are met and there is compliance with relevant legislation. -

The Early-Medieval Monastery at Portmahomack, Tarbat Ness

This is a repository copy of An Iona of the East : the early-medieval monastery at Portmahomack, Tarbat Ness. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/1830/ Article: Carver, Martin orcid.org/0000-0002-7981-5741 (2004) An Iona of the East : the early- medieval monastery at Portmahomack, Tarbat Ness. Medieval Archaeology. pp. 1-30. ISSN 0076-6097 https://doi.org/10.1179/007660904225022780 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ An Iona of the East: The Early-medieval Monastery at Portmahomack, Tarbat Ness By MARTIN CARVER A NEW research programme located on the Tarbat peninsula in north-east Scotland oVers the first large-scale exposure of a monastery in the land of the Picts. A case is argued that the settlement at Portmahomack was founded in the 6th century, possibly by Columba himself, and by the 8th century had developed into an important political and industrial centre comparable with Iona. -

Erection of Polytunnels at Hilton of Cadboll Primary School, Tain By

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Agenda Item 4.3 CAITHNESS, SUTHERLAND & EASTER ROSS PLANNING Report No PLC/052/11 APPLICATIONS COMMITTEE – 25 OCTOBER 2011 11/02367/FUL: Seaboard Memorial Hall Hilton of Cadboll Primary School, Hilton of Cadboll, Tain, IV20 1XR Report by Area Planning Manager SUMMARY Description: Erection of polytunnels Recommandation: GRANT Ward: 08 - Tain And Easter Ross Development category: Local Pre-determination hearing: None Reason referred to Committee: Development on Council owned land. 1. PROPOSAL 1.1 This application seeks permission to erect two polytunnels. The polytunnels will measure 4.267m wide x 6.096m long x 2.286m high and will be covered in a translucent white material. 1.2 The polytunnels will be used as part of a community growing project. 2. SITE DESCRIPTION 2.1 The site is part of the playground at Hilton of Cadboll Primary School. The polytunnels will be erected next to the school building. The site is already laid out with paving slabs as shown on the plan. 3. PLANNING HISTORY 3.1 None known 4. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION 4.1 Advertised: Neighbour Notification Representation deadline: 14 October 2011 Timeous representations: None Late representations: None 5. CONSULTATIONS 5.1 None 6. POLICY The proposed development complies with Development Plan policy. There are no 6.1 policy implications arising from this proposal. 7. PLANNING APPRAISAL 7.1 Section 25 of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 requires planning applications to be determined in accordance with the development plan unless material considerations indicate otherwise. 7.2 This is a straightforward application involving a minor development and is referred to Committee because it is a development in which the Council has an interest. -

Pictish Trail

The Highland PICTISH TRAIL A guide to Pictish sculpture from Inverness to Dunrobin KEY 0 5 10 15 20km Town or Village DUNROBIN BRORA Pictish Stone Site 17 CASTLE A9 Recommended Pictish Trail Route MUSEUM Alternative Route Links Based upon The Ordnance Survey mapping © Crown copyright. 17 Dunrobin Castle N The Highland Council LA09036L. A9 Trunk Road Planning & Development Service. Feb 2002 (hqpldm) A9 GOLSPIE Arabella Roundabout Pictish Trail Guide BONAR BRIDGE ARDGAY ST DEMHAN’S CROSS A949 Moray Firth “Mysterious and often beautiful, Pictish sculpture presents KINCARDINE OLD CHURCH 15 16 DORNOCH one of the great puzzles of Dark Age archaeology” A9 TARBAT (Joanna Close-Brooks 1989) A836 CLACH Dornoch Firth DISCOVERY 14 CENTRE BIORACH 13 A PORTMAHOMACK 9 11 B 9 EDDERTON 1 TAIN 12 7 CHURCH 6 B9174 The Route YARD TAIN A 65 9 91 MUSEUM B Leaving Inverness, follow the A9 northwards over the B 9 10 9 1 HILTON OF CADBOLL Kessock Bridge to the Black Isle. A 7 ROSSKEEN 5 9 BALINTORE Follow signs for Groam House Museum, Rosemarkie. ARDROSS 6 THIEF’S STONE SHANDWICK A9 17 8 8 NIGG OLD From here you can either continue across the Cromarty - 6 B 7 1 7 CHURCH Nigg car ferry (seasonal - to check timetable contact local 9 B tourist offices) or follow the coast road around the Black INVERGORDON Ferry (2 car - summer only) 9 CROMARTY Isle to Dingwall and Strathpeffer. A th ir F DINGWALL ty 63 EAGLE CHURCHYARD ar 91 Sites 8 - 13 are signposted from the A9 at the Arabella m B 2 STONE ro 3 2 C 8 roundabout ( on the map). -

The Case of Hilton Cadboll

by Sign Jones Published by Historic Scotland ISBN 1 903570 43 3 O Sign Jones Edinburgh 2004 Research grant-aided by ANCIENT MONUMENTS DIVISION Author Dr Si2n Jones, School of Art History and Archaeology, University of Manchester Cover photograph Colin Muir (Historic Scotland) and Barry Grove prepare the uplift of the lower portion of the Hilton of Cadboll cross-slab, summer 2001 (Crown copyright: Historic Scotland). EARLYMEDIEVAL SCULPTURE AND THE PRODUCTIONOF MEANING, VALUE AND PLACE:THE CASE OF HILTONOF CADBOLL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Names and identities wealth of invaluable information about the economic Carrying out social research in relation to the of the and the biography of a monument of national renown with a initiatives of the last decade. Alistair and Donna unique biography raises specific problems not Macka~were generous with their time going Over dissimilar from those addressed by Sharon Macdonald video footage of village events from the last decade and (2002, 13) in her ethnography of the Science Museum. providing insight into the views Of a younger It is not feasible to conceal the identity of the generation. In addition to those already mentioned I am monument and by association the communities and also indebted to the following for their participation institutions with which it is connected. The monument and hospitality: Robert Aburrow, Rose Allen, Elizabeth is named after the village of Hilton of Cadboll, and Jeanette Camison* Eassonl Margo national and regional heritage agencies, such as Forrest, Joyce Gartside, Jim L~le,GeOrge MacdOnald, Historic Scotland and the Highland Council Jill Maclarin, Vivien MacClennan, Marion Mackay, the Archaeology Section, play specific roles in relation to late Iain MacPherson, Pauline Mackay, Hugh it by virtue of their institutional remits. -

Item Skye, Ross and Cromarty Area Committee Report SRC/043/15 5 August 2015 No

The Highland Council Agenda 13b Item Skye, Ross and Cromarty Area Committee Report SRC/043/15 5 August 2015 No Tain Associated School Group Overview Report by Director of Care and Learning Summary This report provides an update of key information in relation to the schools within the Tain Associated School Group (ASG), and provides useful updated links to further information in relation to these schools. 1.0 ASG Profile The primary schools in this area serve over 650 pupils, with the secondary school serving 476 young people. ASG roll projections can be found at: http://www.highland.gov.uk/downloads/file/11933/tain There are currently no Head Teacher vacancies in the ASG and all schools receive support through the Quality Improvement Team and the Area Office. 1.1 Attainment and Achievement Attainment – Performance Summary The training session or Elected Members on the new attainment data will take place during the next school term and full attainment data analysis will be provided thereafter, either at Area Committee or at Ward Business Meetings (or both). 1.1.2 Wider Achievement and Notable Successes Secondary – Link to Tain Royal Academy webpage Primary by School: School Link to School Webpage Craighill Primary School Craighill Primary webpage Edderton Primary School Edderton Primary webpage Gledfield Primary School Gledfield Primary webpage Hill of Fearn Primary School Hill of Fearn Primary webpage Hilton of Cadboll Primary School Hilton of Cadboll Primary webpage Inver Primary School Inver Primary webpage Knockbreck Primary School -

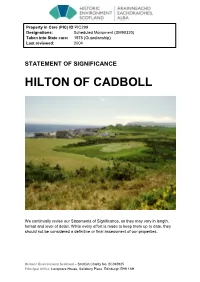

Hilton of Cadboll Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC299 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90320) Taken into State care: 1978 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HILTON OF CADBOLL We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HILTON OF CADBOLL BRIEF DESCRIPTION Hilton of Cadboll chapel is sited near the shore to the NNE of the modern village of Hilton in the Highland parish of Fearn, at the centre of a natural amphitheatre defined by former sea cliffs.