Primary Care in the COVID-19 Pandemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congratulations

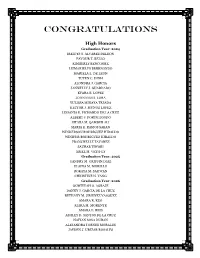

CONGRATULATIONS High Honors Graduation Year: 2024 IREIDYS Y. ALVAREZ DELEON FAVOUR T. BELLO KIMBERLY BENCOSME LIZMARIELYS BERREONDO MARIELA L. DE LEON TUYEN C. DINH ALONDRA J. GARCIA JANNELLY J. GUARDADO KYARA E. LOPEZ JOHNANGEL LORA YULISSA MINAYA TEJADA HECTOR J. MUNOZ LOPEZ LISSANIA E. PICHARDO DE LA CRUZ ALBERT J. PORTUHONDO SITARA M. QAMBER ALI MARIA E. RAMOS SABAN WINDERSON RODRIGUEZ HIRALDO WINIFER RODRIGUEZ HIRALDO FRANCHELLE TAVAREZ SAURAB TIWARI ARIEL M. VETH-LY Graduation Year: 2025 YANDRY M. GRIFFIN DIAZ ELAINA M. MORILLO ROKAYA M. SAHWAN CHRISTINE N. YANG Graduation Year: 2026 QOWIYYAH O. AGBAJE DANNY J. GARCIA DE LA CRUZ BETHANY M. JIMENEZ VASQUEZ AMARA R. KEO KIARA M. MORENTE AMARA E. REIS ASHLEY D. SANTOS DE LA CRUZ NAIYAN SOSA DURAN ALEJANDRA TORNES MORALES JAYDEN J. URIZAR ROSALES Honors Graduation Year: 2024 JOSELYN E. ALONZO XAVIEA S. BROWN PRECIOUS F. BUWEE WILBERT CABRAL GARCIA KALIYAN N. CHHUN JUANA CHIJAL JESSICA A. CHOCOJ CHALI DOMINGO COLAJ COLAJ MARIALYS I. CRUZ ASHLEY M. DE LA CRUZ ARIAS ARDENIS J. DEL ROSARIO GIANA N. DICENZO BRIANNA M. DOMINGUEZ FRIAS SOMALY DONG OSMERY ESTRELLA VARGAS ERICA O. FELIX HERRERA EDUARDO J. GIL ALFONSO BRYAN M. GIRON LUX VILMA GODINEZ SEBASTIANA JERONIMO ALONZO HENRY L. JOHNSON IV TATYANA JOHNSON KRISSBEILY MARTE FERREIRA GEARA D. MATOS DIEGO A. NAVAS ORTES OLIVIER NGABONZIZA MANUELA NUNEZ HERNANDEZ AMBER K. O'BRIEN NICERLIS OLIVO NUNEZ ANDERSON E. ORTEGA-LOPEZ YENEDELI E. PENA GUZMAN FRANCISCO PEREZ RAMOS RENE G. REYES EMILY A. RINDA BETHZY M. ROBLES URIZAR CRISTIAN D. ROSALES HERNANDEZ JASON S. RUSH JAMES D. SEFFENS III GENESIS SOSA ALEXANDER SUAREZ LIZZETTE M. -

Evaluation & Research Literature: the State of Knowledge on BJA

Evaluation & Research Literature: The State of Knowledge on BJA-Funded Programs March 27, 2015 Overview The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) is a leader in developing and implementing evidence-based criminal justice policy and practice. BJA’s mission is to provide leadership in services and grant administration and criminal justice policy development to support local, state, and Tribal justice strategies to achieve safer communities. This is accomplished in many criminal justice topic areas, including adjudication, corrections, counter-terrorism, crime prevention, justice information sharing, law enforcement, justice and mental health, substance abuse, and Tribal justice. Under each topic area, BJA funds numerous programs and initiatives at the Tribal, local, and state level. In partnership with the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), other Federal partners, and many other research partners, many of these programs have been evaluated, while others have not. The intent of the following report is to assess the state of knowledge as determined by data collection, research, and evaluation of and related to BJA- funded programs. This report is a resource that can be a reference for both evaluation and research literature on many BJA programs. It also identifies programs and practices for which U.S. Department of Justice resources have played a critical role in generating innovative programs and sound practices. This report identifies programs and practices with a solid foundation of evidence, as well as those that may benefit from further research and evaluation. Program evaluation is a systematic, objective process for determining the success of a policy or program. Evaluations assess whether and to what extent the program is achieving its goals and objectives. -

Patient Care Through Telepharmacy September 2016

Patient Care through Telepharmacy September 2016 Gregory Janes Objectives 1. Describe why telepharmacy started and how it has evolved with technology 2. Explain how telepharmacy is being used to provide better patient care, especially in rural areas 3. Understand the current regulatory environment around the US and what states are doing with regulation Agenda ● Origins of Telepharmacy ● Why now? ● Telepharmacy process ● Regulatory environment ● Future Applications Telepharmacy Prescription verification CounselingPrescription & verification Education History Origins of Telepharmacy 1942 Australia’s Royal Flying Doctor Service 2001 U.S. has first state pass telepharmacy regulation 2003 Canada begins first telepharmacy service 2010 Hong Kong sees first videoconferencing consulting services US Telepharmacy Timeline 2001 North Dakota first state to allow 2001 Community Health Association in Spokane, WA launches program 2002 NDSU study begins 2003 Alaska Native Medical Center program 2006 U.S. Navy begins telepharmacy 2012 New generation begins in Iowa Question #1 What was the first US state to allow Telepharmacy? a) Alaska b) North Dakota c) South Dakota d) Hawaii Question #1 What was the first US state to allow Telepharmacy? a) Alaska b) North Dakota c) South Dakota d) Hawaii NDSU Telepharmacy Study Study from 2002-2008 ● 81 pharmacies ○ 53 retail and 28 hospital ● Rate of dispensing errors <1% ○ Compared to national average of ~2% ● Positive outcomes, mechanisms could be improved Source: The North Dakota Experience: Achieving High-Performance -

Preventive Health Care

PREVENTIVE HEALTH CARE DANA BARTLETT, BSN, MSN, MA, CSPI Dana Bartlett is a professional nurse and author. His clinical experience includes 16 years of ICU and ER experience and over 20 years of as a poison control center information specialist. Dana has published numerous CE and journal articles, written NCLEX material, written textbook chapters, and done editing and reviewing for publishers such as Elsevire, Lippincott, and Thieme. He has written widely on the subject of toxicology and was recently named a contributing editor, toxicology section, for Critical Care Nurse journal. He is currently employed at the Connecticut Poison Control Center and is actively involved in lecturing and mentoring nurses, emergency medical residents and pharmacy students. ABSTRACT Screening is an effective method for detecting and preventing acute and chronic diseases. In the United States healthcare tends to be provided after someone has become unwell and medical attention is sought. Poor health habits play a large part in the pathogenesis and progression of many common, chronic diseases. Conversely, healthy habits are very effective at preventing many diseases. The common causes of chronic disease and prevention are discussed with a primary focus on the role of health professionals to provide preventive healthcare and to educate patients to recognize risk factors and to avoid a chronic disease. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 1 Policy Statement This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the policies of NurseCe4Less.com and the continuing nursing education requirements of the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation for registered nurses. It is the policy of NurseCe4Less.com to ensure objectivity, transparency, and best practice in clinical education for all continuing nursing education (CNE) activities. -

In Silence Genesis 22 Some of Life's Deepest Mysteries Are Examined In

In Silence Genesis 22 Some of life’s deepest mysteries are examined in Bible stories. Through the centuries, for example, many have tried to make sense out of the narrative recorded in Genesis 22, one of the darkest, most difficult stories that humans have ever told each other. This account begins with a shout. It’s only one word long. Abraham is at home with his wife, his servants. We don’t know what he’s doing at this moment. It’s probably an ordinary day. When suddenly Abraham hears a voice. The voice says to him one word: “Abraham!” This is not just a voice. This is the voice of God, the Creator of the Universe calling to one man, to Abraham. Not for the first time, not at all. When Abraham was younger, God appeared to him and told him to leave his home, which Abraham did. And then God told Abraham to go to a strange land, which he did. And then God and Abraham exchanged promises, and made a covenant together, and God told Abraham to send his first son Ishmael away into the desert, which Abraham did. And then God told Abraham that he had a plan to destroy the people of Sodom and Gomorrah. This time Abraham argued with God. They went back and forth – Abraham and God. “Can’t we save those cities, or some people in those cities, or anyone in those cities?” Later God sent angels to tell of the coming of Isaac. So it wasn’t completely out of the ordinary when God came to where Abraham was and called to him. -

News Briefs the Elite Runners Were Those Who Are Responsible for Vive

VOL. 117 - NO. 16 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, APRIL 19, 2013 $.30 A COPY 1st Annual Daffodil Day on the MARATHON MONDAY MADNESS North End Parks Celebrates Spring by Sal Giarratani Someone once said, “Ide- by Matt Conti ologies separate us but dreams and anguish unite us.” I thought of this quote after hearing and then view- ing the horrific devastation left in the aftermath of the mass violence that occurred after two bombs went off near the finish line of the Boston Marathon at 2:50 pm. Three people are reported dead and over 100 injured in the may- hem that overtook the joy of this annual event. At this writing, most are assuming it is an act of ter- rorism while officials have yet to call it such at this time 24 hours later. The Ribbon-Cutting at the 1st Annual Daffodil Day. entire City of Boston is on (Photo by Angela Cornacchio) high alert. The National On Sunday, April 14th, the first annual Daffodil Day was Guard has been mobilized celebrated on the Greenway. The event was hosted by The and stationed at area hospi- Friends of the North End Parks (FOTNEP) in conjunction tals. Mass violence like what with the Rose F. Kennedy Greenway Conservancy and North we all just experienced can End Beautification Committee. The celebration included trigger overwhelming feel- ings of anxiety, anger and music by the Boston String Academy and poetry, as well as (Photo by Andrew Martorano) daffodils. Other activities were face painting, a petting zoo fear. Why did anyone or group and a dog show held by RUFF. -

Terry Pratchett's Discworld.” Mythlore: a Journal of J.R.R

Háskóli Íslands School of Humanities Department of English Terry Pratchett’s Discworld The Evolution of Witches and the Use of Stereotypes and Parody in Wyrd Sisters and Witches Abroad B.A. Essay Claudia Schultz Kt.: 310395-3829 Supervisor: Valgerður Guðrún Bjarkadóttir May 2020 Abstract This thesis explores Terry Pratchett’s use of parody and stereotypes in his witches’ series of the Discworld novels. It elaborates on common clichés in literature regarding the figure of the witch. Furthermore, the recent shift in the stereotypical portrayal from a maleficent being to an independent, feminist woman is addressed. Thereby Pratchett’s witches are characterized as well as compared to the Triple Goddess, meaning Maiden, Mother and Crone. Additionally, it is examined in which way Pratchett adheres to stereotypes such as for instance of the Crone as well as the reasons for this adherence. The second part of this paper explores Pratchett’s utilization of different works to create both Wyrd Sisters and Witches Abroad. One of the assessed parodies are the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm as well as the effect of this parody. In Wyrd Sisters the presence of Grimm’s fairy tales is linked predominantly to Pratchett’s portrayal of his wicked witches. Whereas the parody of “Cinderella” and the fairy tale’s trope is central to Witches Abroad. Additionally, to the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tales, Pratchett’s parody of Shakespeare’s plays is central to the paper. The focus is hereby on the tragedies of Hamlet and Macbeth, which are imitated by the witches’ novels. While Witches Abroad can solely be linked to Shakespeare due to the main protagonists, Wyrd Sisters incorporates both of the aforementioned Shakespeare plays. -

Oklahoma Primary Care Health Care Workforce Gap Analysis

Oklahoma Primary Care Health Care Workforce Gap Analysis DRAFT Prepared by OSU Center for Rural Health OSU Center for Health Sciences Tulsa, Oklahoma June 2015 Table of Contents Table of Figures ..................................................................................................................................................... ii Tables........................................................................................................................................................................ iii Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Background & Data Acquisition ...................................................................................................................... 2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 Primary Care Provider Supply ......................................................................................................................... 3 Primary Care Provider Demand ................................................................................................................... 10 Conclusions .......................................................................................................................................................... 12 Limitations ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Primary Care Network Listing | Healthpartners

DHS-6594C-ENG HealthPartners® Minnesota Senior Health Options (MSHO) (HMO SNP) Network April 2018 – September 2018 PRIMARY CARE NETWORK LISTING Minnesota Counties: Anoka, Benton, Carver, Chisago, Dakota, Hennepin, Ramsey, Scott, Sherburne, Stearns, Washington, Wright HealthPartners 8170 33rd Ave S. P.O. Box 1309 Minneapolis, MN 55440-1309 Member Services: 952-967-7029 or 1-888-820-4285 (TTY/TDD 711) Oct. 1 – Feb. 14 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. CT, seven days a week Feb. 15 – Sept. 30 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. CT, Monday – Friday healthpartners.com/msho HealthPartners is a health plan that contracts with both Medicare and the Minnesota Medical Assistance (Medicaid) program to provide benefits of both programs to enrollees. Enrollment in HealthPartners depends on contract renewal. HealthPartners MSHO Plan 16697_Print April 2018 H2422 108677 DHS Approved 1/25/2018 1-888-820-4285 Attention. If you need free help interpreting this document, call the above number. ያስተውሉ፡ ካለምንም ክፍያ ይህንን ዶኩመንት የሚተረጉምሎ አስተርጓሚ ከፈለጉ ከላይ ወደተጻፈው የስልክ ቁጥር ይደውሉ። مﻻحظة: إذا أردت مساعدة مجانية لترجمة هذه الوثيقة، اتصل على الرقم أعﻻه. သတိ။ ဤစာရြက္စာတမ္းအားအခမဲ့ဘာသာျပန္ေပးျခင္း အကူအညီလုုိအပ္ပါက၊ အထက္ပါဖုုန္းနံပါတ္ကုုိေခၚဆုုိပါ။ kMNt’sMKal’ . ebIG~k¨tUvkarCMnYyk~¬gkarbkE¨bäksarenHeday²tKit«f sUmehATUrs&BÍtamelxxagelI . 請注意,如果您需要免費協助傳譯這份文件,請撥打上面的電話號碼。 Attention. Si vous avez besoin d’une aide gratuite pour interpréter le présent document, veuillez appeler au numéro ci-dessus. Thov ua twb zoo nyeem. Yog hais tias koj xav tau kev pab txhais lus rau tsab ntaub ntawv no pub dawb, ces hu rau tus najnpawb xov tooj saum toj no. -

The Genesis and Development of "Parker's Back"

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1976 The Genesis and Development of "Parker's Back" Kara Pratt Brewer University of the Pacific Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Brewer, Kara Pratt. (1976). The Genesis and Development of "Parker's Back". University of the Pacific, Dissertation. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/3201 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GENESIS AND DEVELOPl'1ENT OF "PARKER'S BACK" by Kara Brewer An essay subrnitted.in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Arts in the Depa~tment of English University of the Pacific IVJa.rch, 1976 This essay, written and submitted by Kara P. Brewer is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council, University of the Pacific. Department Chairman or Dean: Essay Committee: Dated______ ~M~a~v~l~,~l~9~7~6~------------- "Parker's Back" is the last r-:~hort story Flannery 0' Connor wrote before the ravaging· disease Lupus took her• life in August of 1964. When Caroline Gordon visited her "in a hospital a fev1 weeks before her death," she spoke of her concern about finishing it. "She told me that the doc~~ tor had forbidden her to do any work. -

Genesis, Evolution, and the Search for a Reasoned Faith

GENESIS EVOLUTION AND THE SEARCH FOR A REASONED FAITH Mary Katherine Birge, SSJ Brian G. Henning Rodica M. M. Stoicoiu Ryan Taylor 7031-GenesisEvolution Pgs.indd 3 1/3/11 12:57 PM Created by the publishing team of Anselm Academic. Cover art royalty free from iStock Copyright © 2011 by Mary Katherine Birge, SSJ; Brian G. Henning; Rodica M. M. Stoicoiu; and Ryan Taylor. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher, Anselm Academic, Christian Brothers Publications, 702 Terrace Heights, Winona, MN 55987-1320, www.anselmacademic.org. The scriptural quotations contained herein, with the exception of author transla- tions in chapter 1, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible: Catho- lic Edition. Copyright © 1993 and 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 7031 (PO2844) ISBN 978-0-88489-755-2 7031-GenesisEvolution Pgs.indd 4 1/3/11 12:57 PM c ontents Introduction ix .1 Genesis 1 Mary Katherine Birge, SSJ Why Read the Bible in the First Place? 1 A Faithful and Rational Reading of the Bible 6 Oral Tradition and the Composition of the Bible 6 Two Stories, Not One 8 “Cosmogony” and the Ancient Near East 11 Genesis 2–3: The Yahwist Account 12 Disaster: The Babylonian Exile 27 Genesis 1: The Priestly Account 31 .2 Scientific Knowledge and Evolutionary Biology 41 Ryan Taylor Science and Its Methodology 41 The History of Evolutionary Theory 44 The Mechanisms of Evolution 46 Evidence for Evolution 60 Limits of Scientific Knowledge 64 Common Arguments against Evolution from Creationism and Intelligent Design 65 3. -

PRIMARY CARE SECTOR OVERVIEW June 2016

PRIMARY CARE SECTOR OVERVIEW June 2016 Investment banking services are provided by Harris Williams LLC, a registered broker-dealer and member of FINRA and SIPC, and Harris Williams & Co. Ltd, which is and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Harris Williams & Co. is a trade name under which Harris Williams LLC and Harris Williams & Co. Ltd conduct business. TABLE OF CONTENTS I PRIMARY CARE SECTOR OVERVIEW II APPENDIX: SELECT MARKET PARTICIPANTS PRIMARY CARE SECTOR OVERVIEW The delivery and coordination of primary care is taking on renewed and increasing importance as the system’s gatekeeper in the evolving U.S. healthcare landscape. Primary care accounts for nearly $250 billion of annual industry revenue and over 55% of total office-based physician visits1,2 . However, the systematic under-investment of this integral component of the healthcare system has created a number of well publicized challenges, including: • Insufficient supply of new primary care physicians from medical school • Lower compensation vis-à-vis other specialties • Demands of an aging population outstripping system resources • Under-supply of primary care to rural areas . As the initial contact point for patients, the primary care system will increasingly function as the gatekeeper for care coordination and patient referrals for public and private payors and for healthcare systems . Therefore primary care now fills a critical role in the transition from fee-for-service (“FFS”) to value-based care . To meet these challenges new, innovative primary care practice models have emerged to address care coordination, access and quality of care, and cost, including the following four models highlighted in this report: • Medicare Advantage/Managed Medicaid • Employer Sponsored Health Clinics • Retail Clinics • Concierge Clinics .