In Silence Genesis 22 Some of Life's Deepest Mysteries Are Examined In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

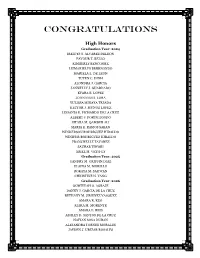

Congratulations

CONGRATULATIONS High Honors Graduation Year: 2024 IREIDYS Y. ALVAREZ DELEON FAVOUR T. BELLO KIMBERLY BENCOSME LIZMARIELYS BERREONDO MARIELA L. DE LEON TUYEN C. DINH ALONDRA J. GARCIA JANNELLY J. GUARDADO KYARA E. LOPEZ JOHNANGEL LORA YULISSA MINAYA TEJADA HECTOR J. MUNOZ LOPEZ LISSANIA E. PICHARDO DE LA CRUZ ALBERT J. PORTUHONDO SITARA M. QAMBER ALI MARIA E. RAMOS SABAN WINDERSON RODRIGUEZ HIRALDO WINIFER RODRIGUEZ HIRALDO FRANCHELLE TAVAREZ SAURAB TIWARI ARIEL M. VETH-LY Graduation Year: 2025 YANDRY M. GRIFFIN DIAZ ELAINA M. MORILLO ROKAYA M. SAHWAN CHRISTINE N. YANG Graduation Year: 2026 QOWIYYAH O. AGBAJE DANNY J. GARCIA DE LA CRUZ BETHANY M. JIMENEZ VASQUEZ AMARA R. KEO KIARA M. MORENTE AMARA E. REIS ASHLEY D. SANTOS DE LA CRUZ NAIYAN SOSA DURAN ALEJANDRA TORNES MORALES JAYDEN J. URIZAR ROSALES Honors Graduation Year: 2024 JOSELYN E. ALONZO XAVIEA S. BROWN PRECIOUS F. BUWEE WILBERT CABRAL GARCIA KALIYAN N. CHHUN JUANA CHIJAL JESSICA A. CHOCOJ CHALI DOMINGO COLAJ COLAJ MARIALYS I. CRUZ ASHLEY M. DE LA CRUZ ARIAS ARDENIS J. DEL ROSARIO GIANA N. DICENZO BRIANNA M. DOMINGUEZ FRIAS SOMALY DONG OSMERY ESTRELLA VARGAS ERICA O. FELIX HERRERA EDUARDO J. GIL ALFONSO BRYAN M. GIRON LUX VILMA GODINEZ SEBASTIANA JERONIMO ALONZO HENRY L. JOHNSON IV TATYANA JOHNSON KRISSBEILY MARTE FERREIRA GEARA D. MATOS DIEGO A. NAVAS ORTES OLIVIER NGABONZIZA MANUELA NUNEZ HERNANDEZ AMBER K. O'BRIEN NICERLIS OLIVO NUNEZ ANDERSON E. ORTEGA-LOPEZ YENEDELI E. PENA GUZMAN FRANCISCO PEREZ RAMOS RENE G. REYES EMILY A. RINDA BETHZY M. ROBLES URIZAR CRISTIAN D. ROSALES HERNANDEZ JASON S. RUSH JAMES D. SEFFENS III GENESIS SOSA ALEXANDER SUAREZ LIZZETTE M. -

Evaluation & Research Literature: the State of Knowledge on BJA

Evaluation & Research Literature: The State of Knowledge on BJA-Funded Programs March 27, 2015 Overview The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) is a leader in developing and implementing evidence-based criminal justice policy and practice. BJA’s mission is to provide leadership in services and grant administration and criminal justice policy development to support local, state, and Tribal justice strategies to achieve safer communities. This is accomplished in many criminal justice topic areas, including adjudication, corrections, counter-terrorism, crime prevention, justice information sharing, law enforcement, justice and mental health, substance abuse, and Tribal justice. Under each topic area, BJA funds numerous programs and initiatives at the Tribal, local, and state level. In partnership with the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), other Federal partners, and many other research partners, many of these programs have been evaluated, while others have not. The intent of the following report is to assess the state of knowledge as determined by data collection, research, and evaluation of and related to BJA- funded programs. This report is a resource that can be a reference for both evaluation and research literature on many BJA programs. It also identifies programs and practices for which U.S. Department of Justice resources have played a critical role in generating innovative programs and sound practices. This report identifies programs and practices with a solid foundation of evidence, as well as those that may benefit from further research and evaluation. Program evaluation is a systematic, objective process for determining the success of a policy or program. Evaluations assess whether and to what extent the program is achieving its goals and objectives. -

Religion and Realpolitik: Reflections on Sacrifice

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 11-2014 Religion and Realpolitik: Reflections on Sacrifice Carolyn Marvin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons, Other Religion Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Marvin, C. (2014). Religion and Realpolitik: Reflections on Sacrifice. Political Theology, 15 (6), 522-535. https://doi.org/10.1179/1462317X14Z.00000000097 Preprint version. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/375 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Religion and Realpolitik: Reflections on Sacrifice Abstract Enduring groups that seek to preserve themselves, as sacred communities do, face a structural contradiction between the interests of individual group members and the survival interests of the group. In addressing existential threats, sacred communities rely on a spectrum of coercive and violent actions that resolve this contradiction in favor of solidarity. Despite different histories, this article argues, nationalism and religiosity are most powerfully organized as sacred communities in which sacred violence is extracted as sacrifice from community members. The exception is enduring groups that are able to rely on the protection of other violence practicing groups. The argument rejects functionalist claims that sacrifice guarantees solidarity or survival, since sacrificing groups regularly fail. In a rereading of Durkheim’s totem taboo, it is argued that sacred communities cannot survive a permanent loss of sacrificial assent on the part of members. Producing this assent is the work of ritual socialization. The deployment of sacrificial violence on behalf of group survival, though deeply sobering, is best constrained by recognizing how violence holds sacred communities in thrall rather than by denying the links between them. -

News Briefs the Elite Runners Were Those Who Are Responsible for Vive

VOL. 117 - NO. 16 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, APRIL 19, 2013 $.30 A COPY 1st Annual Daffodil Day on the MARATHON MONDAY MADNESS North End Parks Celebrates Spring by Sal Giarratani Someone once said, “Ide- by Matt Conti ologies separate us but dreams and anguish unite us.” I thought of this quote after hearing and then view- ing the horrific devastation left in the aftermath of the mass violence that occurred after two bombs went off near the finish line of the Boston Marathon at 2:50 pm. Three people are reported dead and over 100 injured in the may- hem that overtook the joy of this annual event. At this writing, most are assuming it is an act of ter- rorism while officials have yet to call it such at this time 24 hours later. The Ribbon-Cutting at the 1st Annual Daffodil Day. entire City of Boston is on (Photo by Angela Cornacchio) high alert. The National On Sunday, April 14th, the first annual Daffodil Day was Guard has been mobilized celebrated on the Greenway. The event was hosted by The and stationed at area hospi- Friends of the North End Parks (FOTNEP) in conjunction tals. Mass violence like what with the Rose F. Kennedy Greenway Conservancy and North we all just experienced can End Beautification Committee. The celebration included trigger overwhelming feel- ings of anxiety, anger and music by the Boston String Academy and poetry, as well as (Photo by Andrew Martorano) daffodils. Other activities were face painting, a petting zoo fear. Why did anyone or group and a dog show held by RUFF. -

Genesis, Evolution, and the Search for a Reasoned Faith

GENESIS EVOLUTION AND THE SEARCH FOR A REASONED FAITH Mary Katherine Birge, SSJ Brian G. Henning Rodica M. M. Stoicoiu Ryan Taylor 7031-GenesisEvolution Pgs.indd 3 1/3/11 12:57 PM Created by the publishing team of Anselm Academic. Cover art royalty free from iStock Copyright © 2011 by Mary Katherine Birge, SSJ; Brian G. Henning; Rodica M. M. Stoicoiu; and Ryan Taylor. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher, Anselm Academic, Christian Brothers Publications, 702 Terrace Heights, Winona, MN 55987-1320, www.anselmacademic.org. The scriptural quotations contained herein, with the exception of author transla- tions in chapter 1, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible: Catho- lic Edition. Copyright © 1993 and 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 7031 (PO2844) ISBN 978-0-88489-755-2 7031-GenesisEvolution Pgs.indd 4 1/3/11 12:57 PM c ontents Introduction ix .1 Genesis 1 Mary Katherine Birge, SSJ Why Read the Bible in the First Place? 1 A Faithful and Rational Reading of the Bible 6 Oral Tradition and the Composition of the Bible 6 Two Stories, Not One 8 “Cosmogony” and the Ancient Near East 11 Genesis 2–3: The Yahwist Account 12 Disaster: The Babylonian Exile 27 Genesis 1: The Priestly Account 31 .2 Scientific Knowledge and Evolutionary Biology 41 Ryan Taylor Science and Its Methodology 41 The History of Evolutionary Theory 44 The Mechanisms of Evolution 46 Evidence for Evolution 60 Limits of Scientific Knowledge 64 Common Arguments against Evolution from Creationism and Intelligent Design 65 3. -

Genesis (In the Beginning...) Written By: Dennis Byrd

Genesis (In the Beginning...) written by: Dennis Byrd Spoken Intro: In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth Then the earth was without form and void And darkness was upon the face of the deep And the spirit of God - - moved upon the face of the waters. Musical Intro (4x) Unison: Genesis, Genesis, Genesis, Genesis (4x) (Parts): In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth SPOKEN: God! Musical Interlude (4x) Unison: Genesis, Genesis, Genesis, Genesis (4x) (Parts): Then the earth was without form and void And darkness was upon…the face of the deep And the spi-rit of God - - Moved upon the face of the waters. Musical Interlude (2x) Basses: Then God said Tenors: Then God said Altos: Then God said Sopranos: Then God said All: Let..there be light! Basses: And there was…light! Basses: And God saw the light Tenors: And God saw the light Altos: And God saw the light Sopranos: And God saw the light Basses: And...it…was……good! Musical Interlude (2x) Then God divided the light from the darkness The light He called day The darkness He called night And the evening and morning was the first day (2x) SPOKEN: And God said “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters” Choir: Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters SPOKEN: And God made the firmament Choir: Yes He did! SPOKEN: And God divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament And divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament SPOKEN: And God said “Let there -

GENESIS: an Agent-Based Model of Interdomain Network Formation, Traffic flow and Economics

GENESIS: An agent-based model of interdomain network formation, traffic flow and economics Aemen Lodhi Amogh Dhamdhere Constantine Dovrolis School of Computer Science CAIDA School of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology University of California San Diego Georgia Institute of Technology [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—We propose an agent-based network formation however, can have a global impact on the economic viability model for the Internet at the Autonomous System (AS) level. of all ASes and the structure of the Internet. The proposed model, called GENESIS, is based on realistic The Internet remains in a persistent state of flux subject to provider and peering strategies, with ASes acting in a myopic and decentralized manner to optimize a cost-related fitness function. changes in various exogenous factors. How will the Internet GENESIS captures key factors that affect the network formation change due to consolidation of content [1], large penetra- dynamics: highly skewed traffic matrix, policy-based routing, ge- tion of video streaming, falling transit prices [2], expanding ographic co-location constraints, and the costs of transit/peering geographic footprint of content providers [3], cheap local agreements. As opposed to analytical game-theoretic models, availability of peering infrastructure at IXPs [4]? We propose which focus on proving the existence of equilibria, GENESIS is a computational model that simulates the network formation a computational agent-based network formation model, called process and allows us to actually compute distinct equilibria (i.e., “GENESIS”, as a tool to study such questions. GENESIS is networks) and to also examine the behavior of sample paths modular and easily extensible, allowing researchers to exper- that do not converge. -

Aztec Human Sacrifice

EIGHT AZTEC HUMAN SACRIFICE ALFREDO LOPÉZ AUSTIN, UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO, ANO LEONARDO LÓPEZ LUJÁN, INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ANTROPOLOGíA E HISTORIA Stereotypes are persistent ideas of reality generally accepted by a social group. In many cases, they are conceptions that simplify and even caricaturize phenomena of a complex nature. When applied to societies or cultures, they l11ayinclude value judgments that are true or false, specific or ambiguous. If the stereotype refers to orie's own tradition, it emphasizes the positive and the virtuous, and it tends to praise: The Greeks are recalled as philosophers and the Romans as great builders. On the other hand, if the stereotype refers to another tradition , it stresses the negative, the faulty, and it tends to denigrate: For many, Sicilians naturally belong to the Mafia, Pygrnies are cannibals, and the Aztecs were cruel sacrificers. As we will see, many lines of evidence confirm that hurnan sacrifice was one the most deeply rooted religious traditions of the Aztecs. However, it is clear that the Aztecs were not the only ancient people that carried out massacres in honor of their gods, and there is insufficient quantitative inforrnation to determine whether the Aztecs were the people who practiced hu- man sacrifice 1110stoften. Indeed, sacred texts, literary works, historie documents, and especially evidence contributed by archaeology and physical anthropology, enable religious historians to determine that the practice of hurnan sacrifice was common in most parts of the ancient world. For exarnple, evidence of sacrifice and can n iba lism has emerged in l11any parts ofEurope, dating to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. -

Sacrifice, Curse, and the Covenant in Paul's Soteriology

SACRIFICE, CURSE, AND THE COVENANT IN PAUL'S SOTERIOLOGY Norio Yamaguchi A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/7419 This item is protected by original copyright Sacrifice, Curse, and the Covenant in Paul’s Soteriology Norio Yamaguchi This thesis is submitted for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Sacrifice, Curse, and the Covenant in Paul’s Soteriology Presented by Norio Yamaguchi For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2015 St Mary’s College University of St Andrews - i - 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Norio Yamaguchi, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2011 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph D in July 2012; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2011 and 2015. I, Norio Yamaguchi, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of language, which was provided by Sandra Peniston-Bird. Date Feb.12 2015 sig nature of candidate 2. -

Ilwu/Pma Joint Disclaimer Los Angeles / Long Beach Casual Processing List

ILWU/PMA JOINT DISCLAIMER LOS ANGELES / LONG BEACH CASUAL PROCESSING LIST Attached is the List of those selected in the February 7, 2017 through March 29, 2017 random draw for potential processing toward Identified Casual status in the Port of Los Angeles/Long Beach. The List will be used in sequence to fill Los Angeles/Long Beach’s need for new casuals. The Joint Port Labor Relations Committee (JPLRC) shall immediately process all ranked applicants from the list after which the list shall be terminated. Any names not initially drawn shall be purged from the process and individuals shall have no rights to consideration for casual application but shall be afforded equal opportunity with others, should a new list be established. Those to whom processing may be offered will be contacted if and when they will be offered testing for potential casual work. Candidates who satisfy all screening and testing requirements will become eligible for placement on the Identified Casual List from which longshore work is dispatched. Make sure you read and understand the full Disclaimer stated below. Submitting a postcard, interest card, or application, having a card selected in a draw, having a card sequenced and placed on a posted List, being contacted for testing/processing, and the stated procedures for casual processing do not offer or guarantee processing, employment or continued employment, particular procedures (including testing or retesting) or promotion. No reliance should be placed upon any of these steps, none of which forms a contract or creates any binding obligations upon PMA or ILWU towards you. The parties to the governing collective bargaining agreement (the “Pacific Coast Longshore Contract Document,” PCLCD), through the JPLRCs may, by joint agreement and in their discretion, at any time without notice, change or revoke the procedures for hiring, promotion, and employment in the longshore industry. -

Introduction EXPLORATION and SACRIFICE: the CULTURAL

Introduction EXPLORATION AND SACRIFICE: THE CULTURAL LOGIC OF ARCTIC DISCOVERY Russell A. POTTER Reprinted from The Quest for the Northwest Passage: British Narratives of Arctic Exploration, 1576-1874, edited by Frédéric Regard, © 2013 Pickering & Chatto. The Northwest Passage in nineteenth-century Britain, 1818-1874 Although this collective work can certainly be read as a self-contained book, it may also be considered as a sequel to our first volume, also edited by Frederic Regard, The Quest for the Northwest Passage: Knowledge, Nation, Empire, 1576-1806, published in 2012 by Pickering and Chatto. That volume, dealing with early discovery missions and eighteenth-century innovations (overland expeditions, conducted mainly by men working for the Hudson’s Bay Company), was more historical, insisting in particular on the role of the Northwest Passage in Britain’s imperial project and colonial discourse. As its title indicates, this second volume deals massively with the nineteenth century. This was the period during which the Northwest Passage was finally discovered, and – perhaps more importantly – the period during which the quest reached an unprecedented level of intensity in Britain. In Sir John Barrow’s – the powerful Second Secretary to the Admiralty’s – view of Britain’s military, commercial and spiritual leadership in the world, the Arctic remained indeed the only geographical discovery worthy of the Earth’s most powerful nation. But the Passage had also come to feature an inaccessible ideal, Arctic landscapes and seascapes typifying sublime nature, in particular since Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein (1818). And yet, for all the attention lavished on the myth created by Sir John Franklin’s overland expeditions (1819-1822, 1825-18271) and above all by the one which would cost him his life (1845-1847), very little research has been carried out on the extraordinary Arctic frenzy with which the British Admiralty was seized between 1818, in the wake of the end of the Napoleonic wars, and 1859, which may be considered as the year the quest was ended. -

“Amphan” Into a Super Cyclone?

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 3 July 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202007.0033.v1 Did COVID-19 lockdown brew “Amphan” into a super cyclone? V. Vinoj* and D. Swain School of Earth, Ocean and Climate Sciences Indian Institute of Technology Bhubaneswar *Email: [email protected] The world witnessed one of the largest lockdowns in the history of mankind ever, spread over months in an attempt to contain the contact spreading of the novel coronavirus induced COVID-19. As billions around the world stood witness to the staggered lockdown measures, a storm brewed up in the urns of the rather hot Bay of Bengal (BoB) in the Indian Ocean realm. When Thailand proposed the name “Amphan” (pronounced as “Um-pun” meaning ‘the sky’), way back in 2004, little did they realize that it was the christening of the 1st super cyclone (Category-5 hurricane) of the century in this region and the strongest on the globe this year. At the peak, Amphan clocked wind speeds of 168 mph (Joint Typhoon Warning Center) with the pressure drop to 925 h.Pa. What started as a depression in the southeast BoB at 00 UTC on 16th May 2020 developed into a Super Cyclone in less than 48 hours and finally made landfall in the evening hours of 20th May 2020 through the Sundarbans between West Bengal and Bangladesh. Did the impact of the COVID-19 induced lockdown drive an otherwise typical pre-monsoon tropical depression into a super cyclone? Global Warming and Tropical Cyclones Tropical cyclones are primarily fueled by the heat released by the oceans.