Measuring Sustainability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CATÁLOGO DE CURSOS 2021 .Com.Mx Spcgroup Ofrecemos Soluciones Personalizadas Para La Industria Que Busca Trascender

CATÁLOGO DE CURSOS 2021 .com.mx spcgroup Ofrecemos soluciones personalizadas para la industria que busca trascender. Somos expertos en consultoría y capacitación a compañías principalmente del ramo manufacturero y de servicios. Nuestra experiencia está enfocada en áreas como Sistemas de Gestión de la Calidad, herramientas y metodologías de Mejora Continua, Supply Chain y Desarrollo del Potencial Humano. La exigencia de la sociedad actual, ha creado la urgente necesidad de eficientizar el trabajo del hombre, por consecuencia se requiere de mayor preparación en temas de calidad, productividad y sobre todo gestión de negocios. Miles de profesionales en México, U.S.A, Caribe y América del Sur avalan nuestra calidad educativa. spcgroup.com.mx 811 477 7475, 811 477 7476 y 442 258 1587 [email protected] ÍNDICE SISTEMAS DE CALIDAD ISO 9001 2015 Sensibilización a Requerimientos (8 horas) .........................................................................................................07 ISO 9001 2015 Interpretación de Requerimientos (16 horas) .......................................................................................................08 ISO 9001 2015 Gestión de Riesgos base ISO 31000 2018 (16 horas) .........................................................................................09 ISO 9001 2015 Auditor Interno base ISO 19011 2018 (16 horas) .................................................................................................10 IATF 16949 2016 Sensibilización Requerimientos (8 horas) .........................................................................................................11 -

Special Edition TQM&E No.3 Vol.33 2005

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ol. 33 2005 3 V o TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT & EXCELLENCE MENADžMENT TOTALNIM KVALITETOM & IZVRSNOST 452-0680 N '' Special edition '' Papers second reviewed and presented at the Third International Working Conference ''Total Quality Management - Advanced and Intelligent Approaches'', held from 30th May to 1st June, 2005, at Belgrade, Serbia. UDK 658.5 YU ISSN 1 YUSQ - QUALITY AND STANDARDIZATION ASSOCIATION OF SERBIA & MONTENEGRO YUSQ - QUALITY AND STANDARDIZATION ASSOCIATION OF SERBIA & MONTENEGRO ASSOCIATION SERBIA & MONTENEGRO FOR QUALITY AND STANDARDS Kneza Miloša 9, 11000 Beograd, Serbia, Phone/fax: ++ 381 11 323 55 15 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT & EXCELLENCE MENADžMENT TOTALNIM KVALITETOM & IZVRSNOST '' Special edition '' Papers second reviewed and presented at the Third International Working Conference ''Total Quality Management – Advanced and Intelligent Approaches'', held from 30th May to 1st June, 2005, at Belgrade, Serbia. UDK 658.5 YU ISSN 1452-0680 No 3. Vol. 33 2005 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL „TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT & EXCELLENCE” Vol. XXXIII, No.3, 2005 FOUNDER AND PUBLISHER: Association Serbia and Montenegro for Quality and Standards (YUSQ), Belgrade EDITOR IN CHIEF: Prof. Dr Vidosav D. Majstorović, mech. eng. Mechanical Engineering Faculty, University of Belgrade, Serbia INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL BOARD: Prof. dr Guenter ARNDT Prof. dr Gunnar SOHLENIUS University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Australia Sweden Prof. dr Daniel BRISAUND Prof. dr Dragutin STANIVUKOVIĆ University of Grenoble, Grenoble, France FTN, Novi Sad, S&M Prof. dr Barrie DALE Prof. dr Herbert OSANNA UMIST, Manchester, England Technical University, Wien, Austria Michel DEBENHAM Prof. dr Tilo PFIEFER Institute of QA, London, England RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany Sofija DJURDJEVIC Prof. dr Hendrik VanBRUSSEL YUQS, Belgrade, S&M Katolike University Leuven, Heverlez, Belgium Prof. -

Quality of Sustainability Reporting Based on Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Guidelines: The

Quality of Sustainability Reporting Based on Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Guidelines: The Impact of Company Characteristics by Wanting He A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Supply Chain Management I.H. Asper School of Business University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Copyright © 2018 by Wanting He i Abstract With the rise in stakeholders’ demand for more transparency and information disclosure, companies are increasingly publishing sustainability reports to improve their public image. The purpose of this thesis is to explore characteristics of companies that have high quality sustainability reports. Based on the extant literature; location, organization size, third-party verification, and ISO certification are potential factors that influence a company’s reporting performance. A statistical rating method, developed using Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) principles, is used to grade sustainability reports. GRI appears to be the most widely used and dominant sustainability reporting guideline. Hypotheses are tested using ANOVA and regression techniques. The results reveal that firm size and ISO certification influence the quality of sustainability reports. Key words: sustainability report; GRI; firm size; third-party verification; location; ISO ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest and sincere gratitude to my awesome advisor Dr. Paul D, Larson, for his guidance and encouragement all the way during my master study. I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Sara Hajmohammad and Prof. Kristina Hunter, for their invaluable time and insightful comments to improve this thesis. Furthermore, I want to thank my family, for their support of any decision I made. -

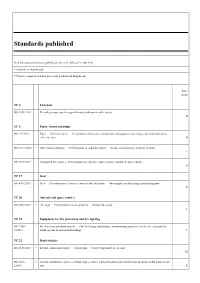

Standards Published

Standards published New International Standards published between 01 July and 31 July 2013 * Available in English only ** French version of standard previously published in English only Price group TC 2 Fasteners ISO 10511:2012 Prevailing torque type hexagon thin nuts (with non-metallic insert) B TC 6 Paper, board and pulps ISO 217:2013 Paper — Untrimmed sizes — Designation and tolerances for primary and supplementary ranges, and indication of ma- chine direction B ISO 10775:2013 * Paper, board and pulps — Determination of cadmium content — Atomic absorption spectrometric method C ISO 3037:2013 Corrugated fibreboard — Determination of edgewise crush resistance (unwaxed edge method) D TC 17 Steel ISO 4967:2013 Steel — Determination of content of non-metallic inclusions — Micrographic method using standard diagrams R TC 20 Aircraft and space vehicles ISO 6517:2013 * Air cargo — Certified lower deck containers — Design and testing L TC 21 Equipment for fire protection and fire fighting ISO 7240- * Fire detection and alarm systems — Part 14: Design, installation, commissioning and service of fire detection and fire 14:2013 alarm systems in and around buildings T TC 22 Road vehicles ISO 6623:2013 * Internal combustion engines — Piston rings — Scraper rings made of cast iron M ISO 6626- * Internal combustion engines — Piston rings — Part 2: Coil-spring-loaded oil control rings of narrow width made of cast 2:2013 iron R ISO 18669- * Internal combustion engines — Piston pins — Part 1: General specifications 1:2013 M ISO 15031- * Road vehicles -

ISO 14031:2021 16065197Cf4d/Iso-14031-2021

INTERNATIONAL ISO STANDARD 14031 Third edition 2021-03 Environmental management — Environmental performance evaluation — Guidelines Management environnemental — Évaluation de la performance environnementale — Lignes directrices iTeh STANDARD PREVIEW (standards.iteh.ai) ISO 14031:2021 https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/sist/0990790c-4bc0-4417-8081- 16065197cf4d/iso-14031-2021 Reference number ISO 14031:2021(E) © ISO 2021 ISO 14031:2021(E) iTeh STANDARD PREVIEW (standards.iteh.ai) ISO 14031:2021 https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/sist/0990790c-4bc0-4417-8081- 16065197cf4d/iso-14031-2021 COPYRIGHT PROTECTED DOCUMENT © ISO 2021 All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, or required in the context of its implementation, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below or ISO’s member body in the country of the requester. ISO copyright office CP 401 • Ch. de Blandonnet 8 CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva Phone:Website: +41 www.iso.org 22 749 01 11 Email: [email protected] iiPublished in Switzerland © ISO 2021 – All rights reserved ISO 14031:2021(E) Contents Page Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................iv -

Environmental Benchmarking for Ipc Industries

ENVIRONMENTAL BENCHMARKING FOR IPC INDUSTRIES FINAL REPORT Prepared for the Environmental Protection Agency by Clean Technology Centre, Cork Institute of Technology Authors: Noel Duffy, Colman Mc Carthy and Matthias Zoehrer ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY An Ghníomhaireacht um Chaomhnú Comhshaoil PO Box 3000, Johnstown Castle, Co.Wexford, Ireland Telephone: +353-53-60600 Fax: +353-53-60699 Email: [email protected] Website: www.epa.ie © Environmental Protection Agency 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report has been prepared as part of the Environmental Research Technological Development and Innovation Programme under the Productive Sector Operational Programme 2000-2006. The programme is financed by the Irish Government under the National Development Plan. It is administered on behalf of the Department of the Environment and Local Government by the Environmental Protection Agency which has the statutory function of co-ordinating and promoting environmental research. DISCLAIMER Although every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the material contained in this publication, complete accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Neither the Environmental Protection Agency nor the author(s) accept any responsibility whatsoever for loss or damage occasioned or claimed to have been occasioned, in part or in full, as a consequence of any person acting, or refraining from acting, as a result of a matter contained in this publication. All or part of this publication may be reproduced without further permission, provided the source is acknowledged. ENVIRONMENTAL BENCHMARKING FOR IPC INDUSTRIES FINAL REPORT Published by the Environmental Protection Agency, Ireland PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER ISBN:1-84095- to come 06/01/300 Price: IR£5/E6.35 Contents Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………i 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................. -

Table of Contents From

Standards, Publications & Software Table of Contents from 34 Construction 89 Medical 110 Petroleum Global Engineering Documents®, the retail arm of IHS, is your single source for individual standards, 136 Telecommunications publications, and integrated collections via hardcopy or electronic delivery. Accessing critical technical 1 Aerospace/Aviation information has never been easier! 7 Annual Book of ASTM Standards global.ihs.com 17 Automotive/Heavy Equipment 25 Boiler & Pressure Vessel Code Copyright © 2004 by Information Handling Services Inc. All rights reserved. 30 CE Marking No portion of this material may be reprinted in any form without the experssed written permission of the publisher, Information Handling Services. Global Engineering Documents and logo are trademarks of Information Handling Services Inc. Registered U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. 32 Color Charts & Standards All other trademarks, brands and product names are the property of their respective owners. 41 Drawing & Drafting 46 Electrical/Electronics 67 Electromagnetic Compatibility/Frequency 70 Environmental 76 Fire Protection 79 Gears 82 Hardware 86 Hydraulics 104 Metals 108 Occupational Health and Safety 120 Plastics 124 Public Health 126 Quality 133 Safety 151 Transportation Management Systems 154 U.S. Government & Military 165 Welding 171 Timesaving Services Free Catalogs Available from Global . 171 Reference Materials & Services . 172 Standards Developing Organization Index . 174 Catalog Index . 177 PRIORITY CODE G040 To order or for more information: 800-854-7179 (USA/Canada) • fax: 303-397-2740 • global.ihs.com Aerospace/Aviation AV DATA® Aerospace Industries Association With AV-DATA® you have access to critical aviation information Global is the worldwide distributor of AIA standards and to help ensure worldwide regulatory compliance, airworthiness, publications. -

Environmental Performance of Digital Printing. Literature Study

VTT CREATES BUSINESS FROM TECHNOLOGY Technology and market foresight • Strategic research • Product and service development • IPR and licensing VTT RESEARCH NOTES 2538 • Assessments, testing, inspection, certification • Technology and innovation management • Technology partnership • • • VTT RESEARCH NOTES 2538 ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE OF DIGITAL PRINTING PERFORMANCE OF DIGITAL 2538 ENVIRONMENTAL • VTT RESEARCH NOTES Digital printing technology has developed considerably in recent years. Electropho- tography and inkjet are gaining ground by enabling new products as well as taking markets from the traditional printing methods. The environmental performance of the digital printing is marketed to be more sustainable than of the traditional print- ing methods. This literature survey looks at digital prining methods and digitally printed products from the environmental standpoint. The report also presents some methods for assessing the environmental performance of digital printing operations at the company level. Furthermore, main environmental indicators, such as energy and materials consumption, are presented. Pentti Viluksela Merja Kariniemi & Minna Nors Environmental performance of digital printing Literature study ISBN 978-951-38-7630-2 (soft back ed.) ISBN 978-951-38-7631-9 (URL: http://www.vtt.fi/publications/index.jsp) ISSN 1235-0605 (soft back ed.) ISSN 1455-0873 (URL: http://www.vtt.fi/publications/index.jsp) VTT TIEDOTTEITA – RESEARCH NOTES 2538 Environmental performance of digital printing Literature study Pentti Viluksela Merja Kariniemi & Minna Nors ISBN 978-951-38-7630-2 (soft back ed.) ISSN 1235-0605 (soft back ed.) ISBN 978-951-38-7631-9 (URL: http://www.vtt.fi/publications/index.jsp) ISSN 1455-0865 (URL: http://www.vtt.fi/publications/index.jsp) Copyright © VTT 2010 JULKAISIJA – UTGIVARE – PUBLISHER VTT, Vuorimiehentie 5, PL 1000, 02044 VTT puh. -

Gap Analysis of the Documents in the ISO 14000-Series with Regard to Quality Management of Environmental Data and Information

Gap analysis of the documents in the ISO 14000-series with regard to quality management of environmental data and information ANN-CHRISTIN PÅLSSON KAROLINA FLEMSTRÖM IMI - Industrial Environmental Informatics for CPM - Centre for Environmental Assessment of Product and Material Systems CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Göteborg, Sweden 2004 CPM Report 2004:3 Table of contents SUMMARY................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 2 Quality management of environmental data and information.......................................................................... 2 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE GAP ANALYSIS.................................................. 4 ISO 14000-series documents included in the analysis........................................................................................ 4 ISO 14000-series documents not included in the analysis ................................................................................. 5 OVERVIEW OF RESULTS FROM THE ANALYSIS.................................................. 6 Data and information............................................................................................................................................ 6 Management of data and information................................................................................................................. 7 Documentation ..................................................................................................................................................... -

SLOVENSKI STANDARD SIST EN ISO 14031:2021 01-Oktober-2021

SLOVENSKI STANDARD SIST EN ISO 14031:2021 01-oktober-2021 Nadomešča: SIST EN ISO 14031:2013 Ravnanje z okoljem - Vrednotenje učinkov ravnanja z okoljem - Smernice (ISO 14031:2021) Environmental management - Environmental performance evaluation - Guidelines Umweltmanagement - Umweltleistungsbewertung - Leitlinien iTeh STANDARD PREVIEW Management environnemental (- sÉvaluationtandar ded sla.i performanceteh.ai) environnementale - Lignes directrices SIST EN ISO 14031:2021 https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/sist/dbe86cb0-d380-4e28-a89c- Ta slovenski standard je istoveten86bed37 z:65cd1/sisENt-en- iISOso-14 014031:202131-2021 ICS: 13.020.10 Ravnanje z okoljem Environmental management SIST EN ISO 14031:2021 en 2003-01.Slovenski inštitut za standardizacijo. Razmnoževanje celote ali delov tega standarda ni dovoljeno. SIST EN ISO 14031:2021 iTeh STANDARD PREVIEW (standards.iteh.ai) SIST EN ISO 14031:2021 https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/sist/dbe86cb0-d380-4e28-a89c- 86bed3765cd1/sist-en-iso-14031-2021 SIST EN ISO 14031:2021 EUROPEAN STANDARD EN ISO 14031 NORME EUROPÉENNE EUROPÄISCHE NORM April 2021 ICS 13.020.10 Supersedes EN ISO 14031:2013 English Version Environmental management - Environmental performance evaluation - Guidelines (ISO 14031:2021) Management environnemental - Évaluation de la Umweltmanagement - Umweltleistungsbewertung - performance environnementale - Lignes directrices Leitlinien (ISO 14031:2021) (ISO 14031:2021) This European Standard was approved by CEN on 17 March 2021. CEN members are bound to comply with the CEN/CENELEC Internal Regulations which stipulate the conditions for giving this European Standard the status of a national standard without any alteration. Up-to-date lists and bibliographical references concerning such national standards may be obtained on application to the CEN-CENELEC Management Centre or to any CEN member. -

Standardiseringsprosjekter Og Nye Standarder

Annonseringsdato: 2012-02-16 Listenummer: 02/2012 Standardiseringsprosjekter og nye standarder Listenummer: 02/2012 Side: 1 av 135 01 Generelt. Terminologi. Standardisering. Dokumentasjon 01 Generelt. Terminologi. Standardisering. Dokumentasjon Standardforslag til høring - europeiske (CEN) prEN 1325 Verdistyring - Vokabular Value Management - Vocabulary Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 22.02.2012 prEN 14190 rev Gypsum plasterboard products from processing - Definitions, requirements and test methods Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 13.03.2012 prEN 15380-5 Railway applications - Classification system for rail vehicles - Part 5: Systems; System groups - System requirements Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 17.04.2012 prEN 16323 Glossary of wastewater engineering terms Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 13.03.2012 prEN ISO 5526 Cereals, pulses and other food grains - Nomenclature (ISO/DIS 5526:2011) Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 13.03.2012 Standardforslag til høring - internasjonale (ISO) ISO 7010:2011/DAmd 115 Safety sign E024: Evacuation temporary refuge Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 26.02.2012 ISO 7010:2011/DAmd 116 Safety sign E025: Emergency call point Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 26.02.2012 ISO 7010:2011/DAmd 117 Safety sign E026: First aid call point Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 26.02.2012 ISO 7010:2011/DAmd 118 Safety sign F007: Fire alarm sounder Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 26.02.2012 ISO 7010:2011/DAmd 109 Safety sign M033: Close safety bar of chairlift Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 20.03.2012 Listenummer: 02/2012 Side: 2 av 135 01 Generelt. Terminologi. Standardisering. Dokumentasjon -

The American University in Cairo School of Sciences and Engineering Environmental Engineering Department

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO SCHOOL OF SCIENCES AND ENGINEERING ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT DEVELOPING INDUSTRIAL RESOURCE SUSTAINABILITY ROADMAP: CEMENT INDUSTRY CASE STUDY By Mary Moharib B.Sc. in Construction Engineering, 2008 A thesis submitted to the School of Science and Engineering in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in EnvironmentaL Engineering Under the supervision of Dr. Salah El-Haggar Chair, Mechanical Engineering Department. The American University in Cairo, Egypt. Fall 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before all, I would like to thank the Lord almighty, for being my guide and strength through every word I have written in this thesis. Without Him, I would not have had the sufficient wisdom or physical strength to get through. I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Salah El Haggar, who’s office door was always open, and who steered me in the right direction whenever needed. Without his role as encourager and advisor, this work would never have been possible. I would like to express my profound gratitude to my parents who continuously provided me with unfailing moral and financial support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study, even through the hardest of times. Their many sacrifices are the reason I am who I am now. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. I would take this opportunity to thank my brother and sister dearly, for consistently helping and supporting me, both morally and physically. Their presence and overwhelming love never failed me. Finally, I would like to thank my husband and my partner for his prayers, support and presence.