By Reason of Religious Training and Belief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nonviolence and Peace Psychology

Nonviolence and Peace Psychology For other titles published in this series, go to www.springer.com/series/7298 Daniel M. Mayton II Nonviolence and Peace Psychology Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, Societal, and World Peace Daniel M. Mayton II Lewis-Clark State College Lewiston ID USA ISBN 978-0-387-89347-1 e-ISBN 978-0-387-89348-8 DOI 10.1007/978-0-387-89348-8 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2009922610 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2009 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Foreword The UNESCO constitution, written in 1945, states, “Since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defenses of peace must be constructed.” This is an appeal for peace psychology. It is a call to understand the values, philoso- phies, and competencies needed to build and maintain intrapersonal, interpersonal, intergroup, and international peace. -

Brock on Curran, 'Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement'

H-Peace Brock on Curran, 'Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement' Review published on Monday, March 1, 2004 Thomas F. Curran. Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement. New York: Fordham University Press, 2003. xv + 228 pp. $45.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8232-2210-0. Reviewed by Peter Brock (Professor Emeritus of History, University of Toronto)Published on H- Peace (March, 2004) Dilemmas of a Perfectionist Dilemmas of a Perfectionist Thomas Curran's monograph originated in a Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Notre Dame but it has been much revised since. The book's clearly written and well-constructed narrative revolves around the person of an obscure package woolen commission merchant from Philadelphia named Alfred Henry Love (1830-1913), a radical pacifist activist who was also a Quaker in all but formal membership. Love is the key figure in the book, binding Curran's chapters together into a cohesive whole. And Love's papers, and particularly his unpublished "Journal," which are located at the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, form the author's most important primary source: in fact, he uses no other manuscript collections, although, as the endnotes and bibliography show, he is well read in the published primary and secondary materials, including work on the general background of both the Civil War era and nineteenth-century pacifism. Curran has indeed rescued Love himself from near oblivion; there is little else on him apart from an unpublished Ph.D. dissertation by Robert W. Doherty (University of Pennsylvania, 1962). -

Historic Peace Churches People

The Consistent Life Ethic the vulnerable to only some groups of Mennonite: From Article 22 of the and the Historic Peace Churches people. Some care for the children in the Mennonite Confession of Faith - womb, children recently born with Mennonites, the Church of the Brethren, and disabilities, and the vulnerable among the ill. “Led by the Spirit, and beginning in the the Religious Society of Friends, which Yet they are not as clear about the problems church, we witness to all people that cooperated together in the "New Call to of war or the death penalty or policies that violence is not the will of God. We witness Peacemaking" project, have centuries of could help solve the problems of poverty against all forms of violence, including war experience in the insights of pacifism. This that threaten the very groups they assert among nations, hostility among races and is the understanding that violence is not protection for. They weaken their case by classes, abuse of children and women, ethical, nor is the apathy or cowardice that their inconsistency. Others are very sensitive violence between men and women, abortion, supports violence by others. Furthermore, to the problems of war and the death penalty and capital punishment.” the appearance of violence as a quick fix to and poverty while using euphemisms to problems is deceptive. Through hardened Brethren: From Pastor Wesley Brubaker, avoid the realities of feticide and infanticide, http://www.brfwitness.org/?p=390 hearts, lost opportunities, and over- and allowing the "right to die" become the simplified thinking, violence generally leads "duty to die" in a society still infested with “We seem to realize instinctively that to more problems and often exacerbates far too many prejudices against the abortion is gruesome. -

Jewish Dimensions of a Free Church Ecclesiology: a Community of Contrast

Jewish Dimensions of a Free Church Ecclesiology: A Community of Contrast A research proposal by drs. Daniël Drost, April 2012 Supervised by Prof. Fernando Enns (promoter). Professor of Mennonite (Peace-) Theology and Ethics, Faculteit der Godgeleerdheid, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Director of the Institute for Peace Church Theology, Hamburg University. Dr. Henk Bakker. Universitair docent Theologie en Geschiedenis van het Baptisme, Faculteit der Godgeleerdheid, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Prof. Peter Tomson (extern). Professor of New Testament, Jewish Studies, and Patristics, Faculteit voor Protestantse Godgeleerdheid Brussel. The provisional title (and subtitle) of the dissertation Jewish Dimensions of a Free Church Ecclesiology: A Community of Contrast A brief description of the issue which the research project will investigate The research will start by investigating John Howard Yoder’s perspective on what he provocatively calls the ‘Jewishness of the Free Church Vision.’ Strongly recommended by Stanley Hauerwas (Duke University), Michael Cartwright (Dean of Ecumenical and Interfaith Programs at the University of Indianapoils) and Peter Ochs (Modern Judaistic Studies at the University of Virginia) posthumously edited and commented on Yoder’s lectures, which he had presented at the Roman- Catholic University of Notre Dame (The Jewish Christian Schism Revisited, 2003). Mennonite theologian Yoder does a firm attempt to relate an Anabaptist (Free Church) ecclesiology to Judaism. Within the tradition of the free churches (independence from government, congregational structure, voluntary membership, emphasis on individual commitment etc.) we can identify characteristics of a self-understanding and an aspired relation to the larger society, which can also be traced in the story of the People of Israel, the Hebrew Bible, Second Temple and rabbinic Diaspora Judaism – Yoder claims. -

Radical Pacifism, Civil Rights, and the Journey of Reconciliation

09-Mollin 12/2/03 3:26 PM Page 113 The Limits of Egalitarianism: Radical Pacifism, Civil Rights, and the Journey of Reconciliation Marian Mollin In April 1947, a group of young men posed for a photograph outside of civil rights attorney Spottswood Robinson’s office in Richmond, Virginia. Dressed in suits and ties, their arms held overcoats and overnight bags while their faces carried an air of eager anticipation. They seemed, from the camera’s perspective, ready to embark on an exciting adventure. Certainly, in a nation still divided by race, this visibly interracial group of black and white men would have caused people to stop and take notice. But it was the less visible motivations behind this trip that most notably set these men apart. All of the group’s key organizers and most of its members came from the emerging radical pacifist movement. Opposed to violence in all forms, many had spent much of World War II behind prison walls as conscientious objectors and resisters to war. Committed to social justice, they saw the struggle for peace and the fight for racial equality as inextricably linked. Ardent egalitarians, they tried to live according to what they called the brotherhood principle of equality and mutual respect. As pacifists and as militant activists, they believed that nonviolent action offered the best hope for achieving fundamental social change. Now, in the wake of the Second World War, these men were prepared to embark on a new political jour- ney and to become, as they inscribed in the scrapbook that chronicled their traveling adventures, “courageous” makers of history.1 Radical History Review Issue 88 (winter 2004): 113–38 Copyright 2004 by MARHO: The Radical Historians’ Organization, Inc. -

Just the Police Function, Then a Response to “The Gospel Or a Glock?”

Just the Police Function, Then A Response to “The Gospel or a Glock?” Gerald W. Schlabach Introduction Consider this thought experiment: Adam and Eve have not yet sinned. In fact, they will not sin for a few decades and have begun their family. It is time for supper, but little Cain and his brother Abel are distracted. They bear no ill will, but their favorite pets, the lion and lamb, are particularly cute as they frolic together this afternoon. So Adam goes to find and hurry them home. With nary an unkind word and certainly no violence, he polices their behavior and orders their community life. For like every social arrangement, even this still-altogether-faithful community requires the police function too. A pacifist who does not recognize this point is likely to misconstrue everything I have written about “just policing.”1 Having lived a vocation for mediating between polarized Christian communities since my years in war- torn Central America, I expected a measure of misunderstanding when I proposed the agenda of just policing as a way to move ecumenical dialogue forward between pacifist and just war Christians, especially Mennonites and Catholics. Whoever seeks to engage the estranged in conversation simultaneously on multiple fronts will take such a risk.2 Deeply held identities are often at stake, and as much as the mediator may do to respect community boundaries, he or she can hardly help but threaten them simply by crossing back and forth. The risk of misunderstanding comes with the liminal territory, and nothing but a doggedly hopeful patience for continued conversation will minimize it. -

Educating for Peace and Justice: Religious Dimensions, Grades 7-12

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 392 723 SO 026 048 AUTHOR McGinnis, James TITLE Educating for Peace and Justice: Religious Dimensions, Grades 7-12. 8th Edition. INSTITUTION Institute for Peace and Justice, St. Louis, MO. PUB DATE 93 NOTE 198p. AVAILABLE FROM Institute for Peace and Justice, 4144 Lindell Boulevard, Suite 124, St. Louis, MO 63108. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Conflict Resolution; Critical Thinking; Cross Cultural Studies; *Global Education; International Cooperation; *Justice; *Multicultural Education; *Peace; *Religion; Religion Studies; Religious Education; Secondary Education; Social Discrimination; Social Problems; Social Studies; World Problems ABSTRACT This manual examines peace and justice themes with an interfaith focus. Each unit begins with an overview of the unit, the teaching procedure suggested for the unit and helpful resources noted. The volume contains the following units:(1) "Of Dreams and Vision";(2) "The Prophets: Bearers of the Vision";(3) "Faith and Culture Contrasts";(4) "Making the Connections: Social Analysis, Social Sin, and Social Change";(5) "Reconciliation: Turning Enemies and Strangers into Friends";(6) "Interracial Reconciliation"; (7) "Interreligious Reconciliation";(8) "International Reconciliation"; (9) "Conscientious Decision-Making about War and Peace Issues"; (10) "Solidarity with the Poor"; and (11) "Reconciliation with the Earth." Seven appendices conclude the document. (EH) * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are -

Jewish-Christian Dialogue Under the Shadow of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Gregory Baum

Document generated on 10/02/2021 6:07 p.m. Théologiques Jewish-Christian Dialogue under the Shadow of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Gregory Baum Juifs et chrétiens. L’à-venir du dialogue. Volume 11, Number 1-2, Fall 2003 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/009532ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/009532ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Faculté de théologie de l'Université de Montréal ISSN 1188-7109 (print) 1492-1413 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Baum, G. (2003). Jewish-Christian Dialogue under the Shadow of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Théologiques, 11(1-2), 205–221. https://doi.org/10.7202/009532ar Tous droits réservés © Faculté de théologie de l'Université de Montréal, 2003 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Théologiques 11/1-2 (2003) p. 205-221 Jewish-Christian Dialogue under the Shadow of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Gregory Baum Religious Studies McGill University Prior to World War II, Jewish religious thinkers who moved beyond the tradition of Orthodoxy were in dialogue with modern culture, including dialogue with Christian thinkers who were also searching new religious responses to the challenge of modernity. -

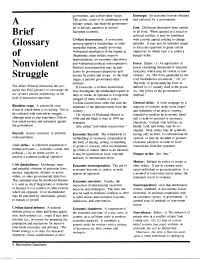

A Brief Glossary of Nonviolent Struggle

government, and subvert their troops. Embargo: An economic boycott initiated This policy, alone or in combination with and enforced by a government. A military means, has received governmen- tal or military attention in several Fast: Deliberate abstention from certain European countries. or all food. When applied in a social or Brief political conflict, it may be combined Civilian insurrection: A nonviolent with a moral appeal seeking to change Glossary uprising against a dictatorship, or other attitudes. It may also be intended simply unpopular regime, usually involving to force the opponent to grant certain widespread repudiation of the regime as objectives, in which case it is called a of illegitimate, mass strikes, massive hunger strike. demonstrations, an economic shut-down, and widespread political noncooperation. Force: Either: (1) An application of Nonviolent Political noncooperation may include power (including threatened or imposed action by government employees and sanctions, which may be violent or non- Struggle mutiny by police and troops. In the final violent). As, "the force generated by the stages, a parallel government often civil disobedience movement." Or: (2) emerges. The body or group applying force as The Albert Einstein Institution has pre- If successful, a civilian insurrection defined in (1), usually used in the plural. pared this brief glossary to encourage the may disintegrate the established regime in As, "the forces at the government's use of more precise terminology in the days or weeks, as opposed to a long-term disposal." field of nonviolent sanctions. struggle of many months or years. Civilian insurrections often end with the General strike: A work stoppage by a Bloodless coup: A successful coup departure of the deposed rulers from the majority of workers in the more impor- d'etat in which there is no killing. -

Fortress of Liberty: the Rise and Fall of the Draft and the Remaking of American Law

Fortress of Liberty: The Rise and Fall of the Draft and the Remaking of American Law Jeremy K. Kessler∗ Introduction: Civil Liberty in a Conscripted Age Between 1917 and 1973, the United States fought its wars with drafted soldiers. These conscript wars were also, however, civil libertarian wars. Waged against the “militaristic” or “totalitarian” enemies of civil liberty, each war embodied expanding notions of individual freedom in its execution. At the moment of their country’s rise to global dominance, American citizens accepted conscription as a fact of life. But they also embraced civil liberties law – the protections of freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly, and procedural due process – as the distinguishing feature of American society, and the ultimate justification for American military power. Fortress of Liberty tries to make sense of this puzzling synthesis of mass coercion and individual freedom that once defined American law and politics. It also argues that the collapse of that synthesis during the Cold War continues to haunt our contemporary legal order. Chapter 1: The World War I Draft Chapter One identifies the WWI draft as a civil libertarian institution – a legal and political apparatus that not only constrained but created new forms of expressive freedom. Several progressive War Department officials were also early civil libertarian innovators, and they built a system of conscientious objection that allowed for the expression of individual difference and dissent within the draft. These officials, including future Supreme Court Justices Felix Frankfurter and Harlan Fiske Stone, believed that a powerful, centralized government was essential to the creation of a civil libertarian nation – a nation shaped and strengthened by its diverse, engaged citizenry. -

The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight It the Story of World War II Conscientious Objectors

Teacher’s Guide Teacher’s Guide: The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight It The Story of World War II conscientious objectors A 58-minute film Available for purchase or rental from Bullfrog Films Produced and Directed by Judith Ehrlich and Rick Tejada-Flores ©2001, Paradigm Productions A production of ITVS, with major funding from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation DVD and special features Produced in collaboration with Lobitos Creek Ranch © 2006 By Judith Ehrlich, Steve Michelson and Dan Newitt To Rent or purchase please contact: Bullfrog Films PO Box 149 Oley, PA 19547 Phone (800) 543-3764 (610) 779-8226 Fax: (610) 370-1978 Web: www.bullfrogfilms.com 1 An Educators’ Guide for The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight It By Judith Ehrlich M.Ed. Overview This program provides insights into profound questions of war and peace, fighting and killing, national security and citizen rights, and responsibilities in a democracy. By telling a little-known story of conscientious objectors to World War II, The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight It offers a new window on the current post–9/11 period of national crises, war and the challenges that face dissenters at such times. Objective The decision to take a public stand as a conscientious objector comes from a deep inner place. It is a decision rooted in one’s spiritual life, faith or belief system rather than in logic or political persuasion. It is not a way to get out of the draft or to avoid life-threatening situations. -

List of Civilian Public Service Camps 1941-1947 from Directory of Civilian Public Service: May, 1941 to March, 1947 (Washington, D.C

List of Civilian Public Service Camps 1941-1947 from Directory of Civilian Public Service: May, 1941 to March, 1947 (Washington, D.C. : National Service Board for Religious Objectors, 1947), pp. x-xvi. No. Technical Agency Operating Group Location State Opening Closing Date Date A Soil Conservation Service American Friends Service Committee Richmond Indiana June 1941 July 1941 1 Forest Service Brethren Service Committee Manistee Michigan June 1941 July 1941 2 Forest Service American Friends Service Committee San Dimas California June 1941 December 1942 3 National Park Service American Friends Service Committee Patapsco Maryland May 1941 September 1942 4 Soil Conservation Service Mennonite Central Committee Grottoes Virginia May 1941 May 1946 5 Soil Conservation Service Mennonite Central Committee Colorado Springs Colorado June 1941 May 1946 6 Soil Conservation Service Brethren Service Committee Lagro Indiana May 1941 November 1944 7 Soil Conservation Service Brethren Service Committee Magnolia Arkansas June 1941 November 1944 8 Forest Service Mennonite Central Committee Marietta Ohio June 1941 April 1943 9 Forest Service American Friends Service Committee Petersham Massachusetts June 1941 October 1942 10 Forest Service American Friends Service Committee Royalston Massachusetts June 1941 October 1942 11 Forest Service American Friends Service Committee Ashburnham Massachusetts June 1941 October 1942 12 Forest Service American Friends Service Committee Cooperstown New York June 1941 May 1945 13 Forest Service Mennonite Central Committee