David Securities V Commonwealth Bank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

Who's That with Abrahams

barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008/09 Who’s that with Abrahams KC? Rediscovering Rhetoric Justice Richard O’Connor rediscovered Bullfry in Shanghai | CONTENTS | 2 President’s column 6 Editor’s note 7 Letters to the editor 8 Opinion Access to court information The costs circus 12 Recent developments 24 Features 75 Legal history The Hon Justice Foster The criminal jurisdiction of the Federal The Kyeema air disaster The Hon Justice Macfarlan Court NSW Law Almanacs online The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina The Hon Justice Ward Saving St James Church 40 Addresses His Honour Judge Michael King SC Justice Richard Edward O’Connor Rediscovering Rhetoric 104 Personalia The current state of the profession His Honour Judge Storkey VC 106 Obituaries Refl ections on the Federal Court 90 Crossword by Rapunzel Matthew Bracks 55 Practice 91 Retirements 107 Book reviews The Keble Advocacy Course 95 Appointments 113 Muse Before the duty judge in Equity Chief Justice French Calderbank offers The Hon Justice Nye Perram Bullfry in Shanghai Appearing in the Commercial List The Hon Justice Jagot 115 Bar sports barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008-09 Bar News Editorial Committee Cover the New South Wales Bar Andrew Bell SC (editor) Leonard Abrahams KC and Clark Gable. Association. Keith Chapple SC Photo: Courtesy of Anthony Abrahams. Contributions are welcome and Gregory Nell SC should be addressed to the editor, Design and production Arthur Moses SC Andrew Bell SC Jeremy Stoljar SC Weavers Design Group Eleventh Floor Chris O’Donnell www.weavers.com.au Wentworth Chambers Duncan Graham Carol Webster Advertising 180 Phillip Street, Richard Beasley To advertise in Bar News visit Sydney 2000. -

THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Law.Adelaide.Edu.Au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD

Volume 40, Number 3 THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW law.adelaide.edu.au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD The Honourable Professor Catherine Branson AC QC Deputy Chancellor, The University of Adelaide; Former President, Australian Human Rights Commission; Former Justice, Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor William R Cornish CMG QC Emeritus Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Cambridge His Excellency Judge James R Crawford AC SC International Court of Justice The Honourable Professor John J Doyle AC QC Former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of South Australia Professor John V Orth William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Professor Emerita Rosemary J Owens AO Former Dean, Adelaide Law School The Honourable Justice Melissa Perry Federal Court of Australia The Honourable Margaret White AO Former Justice, Supreme Court of Queensland Professor John M Williams Dame Roma Mitchell Chair of Law and Former Dean, Adelaide Law School ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Editors Associate Professor Matthew Stubbs and Dr Michelle Lim Book Review and Comment Editor Dr Stacey Henderson Associate Editors Kyriaco Nikias and Azaara Perakath Student Editors Joshua Aikens Christian Andreotti Mitchell Brunker Peter Dalrymple Henry Materne-Smith Holly Nicholls Clare Nolan Eleanor Nolan Vincent Rocca India Short Christine Vu Kate Walsh Noel Williams Publications Officer Panita Hirunboot Volume 40 Issue 3 2019 The Adelaide Law Review is a double-blind peer reviewed journal that is published twice a year by the Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. A guide for the submission of manuscripts is set out at the back of this issue. -

Imagereal Capture

THE HIGH COURT AND THE WORLD OF POLICY BY MICHAEL COPER* Being the last speaker of the day I suppose has advantages and disad vantages. One disadvantage is that, as I had anticipated, much of what I would have wished to say about the Franklin Dam case1 has been said -and well said -by earlier speakers. One advantage, however, is that I may now speak substantially without fear of contradiction - perhaps the "infallibility offinality", as it has sometimes been called,2 is not the exclusive province of the High Court! In any event, I will confine myself to some very general remarks -not so general, I hope, as to be trite, but general enough, at least, to put some of the points we have heard earlier today into perspective. Professor Zines' paper is entitled "The State of Constitutional Inter pretation" .3 My first thought was that this might be a new slogan for Tasmanian number plates - but in the light of the result of the Franklin Dam case I suppose that this would scarcely be appropriate! Professor Zines discusses one of the most fundamental and difficult of all of the problems of constitutional interpretation: what general principles are appropriate, and from whence are they derived. In a way, it is re markable that after eighty years' experience of judicial exegesis and, as Jacobs J was fond of adding, of judicial epexegesis,4 such fundamental issues should be so much in dispute. No doubt the dispute has been narrowed by the decision in the Engineers' case,5 but the permissibility of implications and their nature and content remain at the heart of the controversy. -

Seeing Visions and Dreaming Dreams Judicial Conference of Australia

Seeing Visions and Dreaming Dreams Judicial Conference of Australia Colloquium Chief Justice Robert French AC 7 October 2016, Canberra Thank you for inviting me to deliver the opening address at this Colloquium. It is the first and last time I will do so as Chief Justice. The soft pink tones of the constitutional sunset are deepening and the dusk of impending judicial irrelevance is advancing upon me. In a few weeks' time, on 25 November, it will have been thirty years to the day since I was commissioned as a Judge of the Federal Court of Australia. The great Australian legal figures who sat on the Bench at my official welcome on 10 December 1986 have all gone from our midst — Sir Ronald Wilson, John Toohey, Sir Nigel Bowen and Sir Francis Burt. Two of my articled clerks from the 1970s are now on the Supreme Court of Western Australia. One of them has recently been appointed President of the Court of Appeal. They say you know you are getting old when policemen start looking young — a fortiori when the President of a Court of Appeal looks to you as though he has just emerged from Law School. The same trick of perspective leads me to see the Judicial Conference of Australia ('JCA') as a relatively recent innovation. Six years into my judicial career, in 1992, I attended a Supreme and Federal Courts Judges' Conference at which Justices Richard McGarvie and Ian Sheppard were talking about the establishment of a body to represent the common interests and concerns of judges, to defend the judiciary as an institution and, where appropriate, to defend individual judges who were the target of unfair and unwarranted criticisms. -

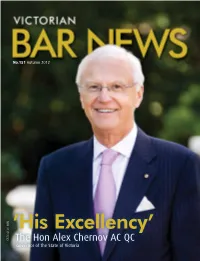

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

Australian Guide to Legal Citation, Third Edition

AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO LEGAL AUSTRALIAN CITATION AUST GUIDE TO LEGAL CITA AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO TO LEGAL CITATION AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO LEGALA CITUSTRATION ALIAN Third Edition GUIDE TO LEGAL CITATION AGLC3 - Front Cover 4 (MJ) - CS4.indd 1 21/04/2010 12:32:24 PM AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO LEGAL CITATION Third Edition Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc in collaboration with Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc Melbourne 2010 Published and distributed by the Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc in collaboration with the Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Australian guide to legal citation / Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc., Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc. 3rd ed. ISBN 9780646527390 (pbk.). Bibliography. Includes index. Citation of legal authorities - Australia - Handbooks, manuals, etc. Melbourne University Law Review Association Melbourne Journal of International Law 808.06634 First edition 1998 Second edition 2002 Third edition 2010 Reprinted 2010, 2011 (with minor corrections), 2012 (with minor corrections) Published by: Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc Reg No A0017345F · ABN 21 447 204 764 Melbourne University Law Review Telephone: (+61 3) 8344 6593 Melbourne Law School Facsimile: (+61 3) 9347 8087 The University of Melbourne Email: <[email protected]> Victoria 3010 Australia Internet: <http://www.law.unimelb.edu.au/mulr> Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc Reg No A0046334D · ABN 86 930 725 641 Melbourne Journal of International Law Telephone: (+61 3) 8344 7913 Melbourne Law School Facsimile: (+61 3) 8344 9774 The University of Melbourne Email: <[email protected]> Victoria 3010 Australia Internet: <http://www.law.unimelb.edu.au/mjil> © 2010 Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc and Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc. -

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Nineteen

Chapter Four Work Choices: A Betrayal of Original Meaning? Eddy Gisonda Originalism stipulates that a search for the original meaning of constitutional terms upon enactment is the only legitimate interpretive method. By its very nature, this is an historical exercise. In particular, it requires a thorough evaluation of Australia’s transition from a collection of independent colonies to a federated Commonwealth. It necessitates taking the temperature as it then was, and giving the attitudes and values of the time a sympathetic ear. A difficult task, it is none the less an enjoyable one. It involves, for a start, immersing oneself in the former British colonies, a time when border duties were paid, travel occurred on three different types of railway gauge, and men with waistcoats and whiskers were elected to office. These peculiar looking gentlemen, of course, became our nation’s founding fathers. Amongst their ranks were such luminaries as Barton, Parkes, Clark and Griffith, all of whom contributed in some way to the Commonwealth Constitution, and whose understanding of that document remains especially crucial. Also involved was Sir George Reid, perhaps the most intriguing of them all. One reason is that it remains incredibly difficult to decipher whether Reid was for the federation project or against it. On 28 March, 1898 hundreds of New South Welshmen crammed into the Sydney Town Hall to hear their Premier’s views on the federation question. Two hours later, they left none the wiser. The bemused commentariat labeled him “Yes-No Reid”, an epithet he carried for the rest of his life.1 A second reason was his love-hate relationship with the Australian people. -

Alumni News2005v11.Indd

POSTCARDS AND LETTERS HONOURS DEATHS (August 2003 – July 2005) OBITUARIES Alumni News Supplement to Trinity Update August 2005 Trinity College 2004 AUSTRALIA DAY HONOURS Dr Yvonne AITKEN, AM (1930) REGINALD LESLIE STOCK, OBE, COLIN PERCIVAL JUTTNER JOHN GORDON RUSHBROOKE THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE Dr Nancy AUN (1976) 1909-2004 1910-2003 1936-2003 Hugh Wilson BALLANTYNE (1951) AC Reg Stock entered Trinity in 1929, studying for a Following in his father’s footsteps, Colin Juttner entered John Rushbrooke entered Trinity from Geelong Grammar in What a kaleidoscope of activities is reflected in this collection of news items, gathered since August 2003 from Peter BALMFORD (1946) Leonard Gordon DARLING (TC 1940), AO, CMG, combined Arts/Law degree. He was elected Secretary Trinity from St Peter’s College, Adelaide, in 1929 and 1954 with a General Exhibition. He completed his BSc in Alumni and Friends of Trinity College, the University of Melbourne. We hope this new trial format will help to Dr (William) Ronald BEETHAM, AM (1949) Melbourne, Victoria. For service to the arts through of the Fleur de Lys Club in 1932 and Senior Student enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine. He took a prominent 1956, graduating with prizes in Mathematics and Physics. rekindle memories and prompt some renewed contacts, and apologise if any details have become dated. vision, advice and philanthropy for long-term benefit Dr Garry Edward Wilbur BENNETT (1938) in 1933. As such he chaired the meeting of the Club part in student life, representing the College in cricket His Master’s degree saw him begin his work as a high to the nation. -

1992 Canliidocs

492 ALBERT A LAW REVIEW [VOL. XXX, NO. 2 1992] THE CRISIS OF CONSTITUTIONAL LITERALISM IN AUSTRALIA GREG CRAVEN* The article acts as an introduction to currelll Le preselll article sert a presenter les debars Australian debates concerning constitutional australie11s actuels en matiere d' interpretation imerpretation. Since the 1920s, the dominalll c,mstitutionnelle. Depuis les a1111ees/920, la theorie imerpretive scheme has been "literalism." Under this dominante a ere cel/e du «litteralisme». c:'est-a-dire theory, the High Court has concerned itself with I' i111erpretation litterale et grammaticale de la finding meaning exclusively within the written text. Comifitution. Regie par cette theorie, la Cour halite This highly tec:lmical approach 10 constitutional s' est attac:hee a 11e trom•er de signification qu' a imerpretation has masked a political agenda of I' interieur du texte ecrit. Cette approche hameme11t cemralising power into the hands of the federal teclmique masque 1111programme politique qui veille gO\·emment. For this and other reasons. literalism a centraliser le pouvoir emre /es mains du is losing favour in Australia and several other gou\'emement federal. Pour cette raison, elllre imerpretil'e strategies are being advanced. The mitres./' interpretation littera/e est en perte de vitesse article concludes by summarising the challengers to en Australie. et plusieurs mttres strategies soil/ literalism, a11alyzing their merits and weaknesses. actuellement proposees. L' article conc/11t en /es and suggesting a symhesis. resumant, en analysallf leurs merites et /eurs 1992 CanLIIDocs 212 faiblesses, et e11 .mggeram qu' on adopte 1me .<;ynthese. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION . 492 II. -

Judges and Retirement Ages

JUDGES AND RETIREMENT AGES ALYSIA B LACKHAM* All Commonwealth, state and territory judges in Australia are subject to mandatory retirement ages. While the 1977 referendum, which introduced judicial retirement ages for the Australian federal judiciary, commanded broad public support, this article argues that the aims of judicial retirement ages are no longer valid in a modern society. Judicial retirement ages may be causing undue expense to the public purse and depriving the judiciary of skilled adjudicators. They are also contrary to contemporary notions of age equality. Therefore, demographic change warrants a reconsideration of s 72 of the Constitution and other statutes setting judicial retirement ages. This article sets out three alternatives to the current system of judicial retirement ages. It concludes that the best option is to remove age-based limitations on judicial tenure. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 739 II Judicial Retirement Ages in Australia ................................................................... 740 A Federal Judiciary .......................................................................................... 740 B Australian States and Territories ............................................................... 745 III Criticism of Judicial Retirement Ages ................................................................... 752 A Critiques of Arguments in Favour of Retirement Ages ........................ -

The Case for Abolishing the Offence of Scandalising the Judiciary

Daniel O’Neil* THE CASE FOR ABOLISHING THE OFFENCE OF SCANDALISING THE JUDICIARY ABSTRACT This article assesses the philosophical foundations and the practical remit of the common law offence of scandalising the judiciary (also known as ‘scandalising contempt’), and finds that the continued existence of this offence as presently constituted cannot be justified. The elements and scope of this offence, it is suggested, are ill-defined, which is a matter of great concern given its potentially fierce penal consequences. Moreover, given the extent to which it may interfere with free expression of opinion on an arm of government, the offence’s compatibility with the implied freedom of political communication guaranteed by the Australian Constitution is also discussed — though it is noted that in most instances, prosecutions for the offence will not infringe this protection. The article concludes by suggesting that the common law offence must either by abolished by legislative fiat or replaced by a more narrowly confined statutory offence. It is suggested that an expression of genuinely held belief on a matter of such profound public interest as the administration of justice should not be the subject of proceedings for contempt of court. I INTRODUCTION ow far can one go in criticising a Judge?’1 This is the question at the heart of the common law offence known as scandalising the judiciary — an ‘H offence that may sound ‘wonderfully archaic’,2 yet is regrettably anything but. This article attempts to chart the metes and bounds of this offence and to assess its empirical application in Australia and elsewhere. It is concluded that the offence is both vague in definition and savage in its potential punitive consequences.