Imagereal Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Environment Is All Rights: Human Rights, Constitutional Rights and Environmental Rights

Advance Copy THE ENVIRONMENT IS ALL RIGHTS: HUMAN RIGHTS, CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RIGHTS RACHEL PEPPER* AND HARRY HOBBS† Te relationship between human rights and environmental rights is increasingly recognised in international and comparative law. Tis article explores that connection by examining the international environmental rights regime and the approaches taken at a domestic level in various countries to constitutionalising environmental protection. It compares these ap- proaches to that in Australia. It fnds that Australian law compares poorly to elsewhere. No express constitutional provision imposing obligations on government to protect the envi- ronment or empowering litigants to compel state action exists, and the potential for draw- ing further constitutional implications appears distant. As the climate emergency escalates, renewed focus on the link between environmental harm and human harm is required, and law and policymakers in Australia are encouraged to build on existing law in developing broader environmental rights protection. CONTENTS I Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 II Human Rights-Based Environmental Protections ................................................... 8 A International Environmental Rights ............................................................. 8 B Constitutional Environmental Rights ......................................................... 15 1 Express Constitutional Recognition .............................................. -

Environmental Governance (Technical Paper 2, 2017)

ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE TECHNICAL PAPER 2 The principal contributions to this paper were provided by the following Panel Members: Adjunct Professor Rob Fowler (principal author), with supporting contributions from Murray Wilcox AO QC, Professor Paul Martin, Dr. Cameron Holley and Professor Lee Godden. .About APEEL The Australian Panel of Experts on Environmental Law (APEEL) is comprised of experts with extensive knowledge of, and experience in, environmental law. Its membership includes environmental law practitioners, academics with international standing and a retired judge of the Federal Court. APEEL has developed a blueprint for the next generation of Australian environmental laws with the aim of ensuring a healthy, functioning and resilient environment for generations to come. APEEL’s proposals are for environmental laws that are as transparent, efficient, effective and participatory as possible. A series of technical discussion papers focus on the following themes: 1. The foundations of environmental law 2. Environmental governance 3. Terrestrial biodiversity conservation and natural resources management 4. Marine and coastal issues 5. Climate law 6. Energy regulation 7. The private sector, business law and environmental performance 8. Democracy and the environment The Panel Adjunct Professor Rob Fowler, University of South The Panel acknowledges the expert assistance and Australia – Convenor advice, in its work and deliberations, of: Emeritus Professor David Farrier, University of Wollongong Dr Gerry Bates, University of Sydney -

Year 10 High Court Decisions - Activity

Year 10 High Court Decisions - Activity Commonly known The Franklin Dam Case 1983 name of the case Official legal title Commonwealth v Tasmania ("Tasmanian Dam case") [1983] HCA 21; (1983) 158 CLR 1 (1 July 1983) Who are the parties involved? Key facts - Why did this come to the High Court? Who won the case? What type of verdict was it? What key points did the High Court make in this case? Has there been a change in the law as a result of this decision? What is the name of this law? Recommended 1. Envlaw.com.au. (2019). Environmental Law Australia | Tasmanian Dam Case. [online] Available at: http://envlaw.com.au/tasmanian-dam-case Resources [Accessed 19 Feb. 2019]. 2. High Court of Australia. (2019). Commonwealth v Tasmania ("Tasmanian Dam case") [1983] HCA 21; (1983) 158 CLR 1 (1 July 1983). [online] Available at: http://www7.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/cth/HCA/1983/21.html [Accessed 19 Feb. 2019] 3. Aph.gov.au. (2019). Chapter 5 – Parliament of Australia. [online] Available at: https://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/senate/legal_and_constitutional_affairs/completed_inquiries/pre1996/treaty/report /c05 [Accessed 20 Feb. 2019. GO TO 5. 31 to find details on this case] 1 The Constitutional Centre of Western Australia Updated September 2019 Year 10 High Court Decisions - Activity Commonly known MaboThe Alqudsi Case Case name of the case Official legal title AlqudsiMabo v vQueensland The Queen [2016](No 2) HCA[1992] 24 HCA 23; (1992) 175 CLR 1 (3 June 1992). Who are the parties Whoinvolved? are the parties involved? Key facts - Why did Keythis comefacts -to Why the did thisHigh come Court? to the High Court? Who won the case? Who won the case? What type of verdict Whatwas it? type of verdict wasWhat it? key points did Whatthe High key Court points make did thein this High case? Court make Hasin this there case? been a Haschange there in beenthe law a as changea result inof thethis law as adecision? result of this Whatdecision? is the name of Whatthis law? is the name of Recommendedthis law? 1. -

MDBRC Submission

SA Dairyfarmers’ Association Inc 8D031 30 April 2018 Mr Bret Walker SC Royal Commissioner Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission GPO Box 1445 Adelaide SA 5001 Dear Commissioner, Please accept this letter as the submission of the South Australian Dairyfarmers Association (SADA) with regard to the Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission. We understand that while you have all of the coercive and attendant powers of a Royal Commission we seek to offer this submission to assist the Commission with its deliberations through the lens of the dairy industry in South Australia. The Constitution of the Royal Commission As a matter openness on our part SADA made critical comments regarding the establishment of the Commission when it was announced by the South Australian Government. We expressed our concern that such a commission would have the effect of limiting public debate at a time that discourse should be at its most pronounced. Major contributors and witnesses who are called to give evidence before Royal Commissions may become more reluctant to speak publicly prior to giving evidence to a Royal Commission or while a Royal Commission is constituted. Considering the matters which are subject to Senate disallowance motions or broadcast by national media outlets having experts in the sphere of influence feeling free to enter into the public debate is important as they bring temperance and evenness that is all too often absent. We express full confidence in established authorities, such as the NSW ICAC, Police Force or any other state or Federal instrumentality in their capacity to deal with any alleged criminality within their jurisdictions and we made comment at the time of the 4 Corners Report into the Murray Darling that these events were not sufficient, within themselves, to enliven the justification for a Royal Commission. -

Human Rights Law and Racial Hate Speech Regulation in Australia: Reform and Replace?

HUMAN RIGHTS LAW AND RACIAL HATE SPEECH REGULATION IN AUSTRALIA: REFORM AND REPLACE? Dr. Alan Berman* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 46 II. INTERNATIONAL LEGAL OBLIGATIONS ............................................ 50 A. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights................ 50 B. The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination ................................................ 56 C. Legislative Attempts to Implement International Treaty Obligations ................................................................................. 63 D. The Current “Racial Hatred” Legislative Landscape ............... 68 E. The Constitutional Position ....................................................... 70 F. Implementation of International Treaty Obligations by Other Western Democracies ...................................................... 75 III. FREE SPEECH JUSTIFICATIONS AND RACIST HATE SPEECH ............. 79 IV. EXISTING LAWS DO NOT FURTHER THE POLICIES OF RACIAL HATE SPEECH REGULATION ............................................................. 82 A. Commonwealth Laws ................................................................. 83 B. State and Territory Laws............................................................ 96 V. CONCLUSION .................................................................................. 101 * Associate Professor of Law, Charles -

Richardson V Forestry Commission.Pdf

High Court of Australia Mason C.J. Mason C.J. Wilson, Brennan, Deane, Dawson, Toohey and Gaudron JJ. Richardson v Forestry Commission (88/007) [1988] HCA 10 ORDER Order that until the hearing and determination of this action, or further order, each defendant by itself, its servants or agents, be restrained from doing any of the following acts during the interim protection period as defined in the Lemonthyme and Southern Forests (Commission of Inquiry) Act 1987 Cth, namely: (a) for the purposes of, or in the course of carrying out, forestry operations, killing, cutting down or damaging any tree in, or removing any tree or part of a tree from, the area defined in the said Act as the protected area; or (b) constructing or establishing any road or vehicular track within the said protected area, except with the consent in writing of the plaintiff given pursuant to the Act. That until the hearing and determination of this action, or further order, the first-named defendant by itself, its servants or agents be restrained from doing any of the following acts during the said interim protection period, namely, permitting, authorizing, directing or ordering or purporting to permit, authorize, direct or order any person to do any act referred to in sub-pars. 1(a) or 1(b) hereof, except with the consent in writing of the plaintiff given pursuant to the said Act. And it is further ordered that the costs of this application be the plaintiff's costs in the action. Answer the questions as follows: 1. Q. To what extent, if any, is the Lemonthyme and Southern Forests (Commission of Inquiry) Act 1987 (Cth) invalid? A. -

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

Who's That with Abrahams

barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008/09 Who’s that with Abrahams KC? Rediscovering Rhetoric Justice Richard O’Connor rediscovered Bullfry in Shanghai | CONTENTS | 2 President’s column 6 Editor’s note 7 Letters to the editor 8 Opinion Access to court information The costs circus 12 Recent developments 24 Features 75 Legal history The Hon Justice Foster The criminal jurisdiction of the Federal The Kyeema air disaster The Hon Justice Macfarlan Court NSW Law Almanacs online The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina The Hon Justice Ward Saving St James Church 40 Addresses His Honour Judge Michael King SC Justice Richard Edward O’Connor Rediscovering Rhetoric 104 Personalia The current state of the profession His Honour Judge Storkey VC 106 Obituaries Refl ections on the Federal Court 90 Crossword by Rapunzel Matthew Bracks 55 Practice 91 Retirements 107 Book reviews The Keble Advocacy Course 95 Appointments 113 Muse Before the duty judge in Equity Chief Justice French Calderbank offers The Hon Justice Nye Perram Bullfry in Shanghai Appearing in the Commercial List The Hon Justice Jagot 115 Bar sports barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008-09 Bar News Editorial Committee Cover the New South Wales Bar Andrew Bell SC (editor) Leonard Abrahams KC and Clark Gable. Association. Keith Chapple SC Photo: Courtesy of Anthony Abrahams. Contributions are welcome and Gregory Nell SC should be addressed to the editor, Design and production Arthur Moses SC Andrew Bell SC Jeremy Stoljar SC Weavers Design Group Eleventh Floor Chris O’Donnell www.weavers.com.au Wentworth Chambers Duncan Graham Carol Webster Advertising 180 Phillip Street, Richard Beasley To advertise in Bar News visit Sydney 2000. -

THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Law.Adelaide.Edu.Au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD

Volume 40, Number 3 THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW law.adelaide.edu.au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD The Honourable Professor Catherine Branson AC QC Deputy Chancellor, The University of Adelaide; Former President, Australian Human Rights Commission; Former Justice, Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor William R Cornish CMG QC Emeritus Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Cambridge His Excellency Judge James R Crawford AC SC International Court of Justice The Honourable Professor John J Doyle AC QC Former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of South Australia Professor John V Orth William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Professor Emerita Rosemary J Owens AO Former Dean, Adelaide Law School The Honourable Justice Melissa Perry Federal Court of Australia The Honourable Margaret White AO Former Justice, Supreme Court of Queensland Professor John M Williams Dame Roma Mitchell Chair of Law and Former Dean, Adelaide Law School ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Editors Associate Professor Matthew Stubbs and Dr Michelle Lim Book Review and Comment Editor Dr Stacey Henderson Associate Editors Kyriaco Nikias and Azaara Perakath Student Editors Joshua Aikens Christian Andreotti Mitchell Brunker Peter Dalrymple Henry Materne-Smith Holly Nicholls Clare Nolan Eleanor Nolan Vincent Rocca India Short Christine Vu Kate Walsh Noel Williams Publications Officer Panita Hirunboot Volume 40 Issue 3 2019 The Adelaide Law Review is a double-blind peer reviewed journal that is published twice a year by the Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. A guide for the submission of manuscripts is set out at the back of this issue. -

Seeing Visions and Dreaming Dreams Judicial Conference of Australia

Seeing Visions and Dreaming Dreams Judicial Conference of Australia Colloquium Chief Justice Robert French AC 7 October 2016, Canberra Thank you for inviting me to deliver the opening address at this Colloquium. It is the first and last time I will do so as Chief Justice. The soft pink tones of the constitutional sunset are deepening and the dusk of impending judicial irrelevance is advancing upon me. In a few weeks' time, on 25 November, it will have been thirty years to the day since I was commissioned as a Judge of the Federal Court of Australia. The great Australian legal figures who sat on the Bench at my official welcome on 10 December 1986 have all gone from our midst — Sir Ronald Wilson, John Toohey, Sir Nigel Bowen and Sir Francis Burt. Two of my articled clerks from the 1970s are now on the Supreme Court of Western Australia. One of them has recently been appointed President of the Court of Appeal. They say you know you are getting old when policemen start looking young — a fortiori when the President of a Court of Appeal looks to you as though he has just emerged from Law School. The same trick of perspective leads me to see the Judicial Conference of Australia ('JCA') as a relatively recent innovation. Six years into my judicial career, in 1992, I attended a Supreme and Federal Courts Judges' Conference at which Justices Richard McGarvie and Ian Sheppard were talking about the establishment of a body to represent the common interests and concerns of judges, to defend the judiciary as an institution and, where appropriate, to defend individual judges who were the target of unfair and unwarranted criticisms. -

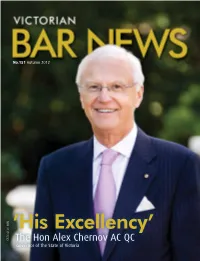

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

Australian Guide to Legal Citation, Third Edition

AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO LEGAL AUSTRALIAN CITATION AUST GUIDE TO LEGAL CITA AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO TO LEGAL CITATION AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO LEGALA CITUSTRATION ALIAN Third Edition GUIDE TO LEGAL CITATION AGLC3 - Front Cover 4 (MJ) - CS4.indd 1 21/04/2010 12:32:24 PM AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO LEGAL CITATION Third Edition Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc in collaboration with Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc Melbourne 2010 Published and distributed by the Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc in collaboration with the Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Australian guide to legal citation / Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc., Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc. 3rd ed. ISBN 9780646527390 (pbk.). Bibliography. Includes index. Citation of legal authorities - Australia - Handbooks, manuals, etc. Melbourne University Law Review Association Melbourne Journal of International Law 808.06634 First edition 1998 Second edition 2002 Third edition 2010 Reprinted 2010, 2011 (with minor corrections), 2012 (with minor corrections) Published by: Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc Reg No A0017345F · ABN 21 447 204 764 Melbourne University Law Review Telephone: (+61 3) 8344 6593 Melbourne Law School Facsimile: (+61 3) 9347 8087 The University of Melbourne Email: <[email protected]> Victoria 3010 Australia Internet: <http://www.law.unimelb.edu.au/mulr> Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc Reg No A0046334D · ABN 86 930 725 641 Melbourne Journal of International Law Telephone: (+61 3) 8344 7913 Melbourne Law School Facsimile: (+61 3) 8344 9774 The University of Melbourne Email: <[email protected]> Victoria 3010 Australia Internet: <http://www.law.unimelb.edu.au/mjil> © 2010 Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc and Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc.