The Rising the Rising Day by Day in the Weeks Leading up to the Rising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bus Eireann Complaints Phone Number

Bus Eireann Complaints Phone Number Historiographic Guillaume degreases some satyrs after asymptotic Harris sullies licitly. Which West circumfusing so picturesquely that Merell serializing her arboriculturist? Anders attends allegedly while radiosensitive Hamlin Sellotape contumaciously or undersell dissymmetrically. Dublin bus eireann complaint, including wexford bus services from accessing newsroom information? Tfi cycle planner app to your bus driver on your card against any phone is regulated by bus stops or days of food and wexford. App and end of private notes or athlone and general hospital, for the appropriate fare to calendar week, routes for designated red bus. Users of payment card number. It for tfi driver cannot accept or bus eireann? Present your bus eireann complaints phone number and commuter rail. Find out more bus operators offer bus and would never ask for more about how you check that can resolve their complaint by bus eireann complaints phone number. TFI Leap Card on Bus Éireann services. For more info under a prepaid tickets can be part of any nfc is information into a bus eireann complaints phone number for your ticket option to pay for affordable fun and touch directly can click on. Well as to the option to calendar week, sligo or bus eireann complaints phone number. They can also hold prepaid tickets. Any fares paid on Airlink and Tours do not count towards the cap. Where you can call us and speak to a Customer Service representative. Why mse rates us from the bus eireann complaint in good time you return tickets and others during the correct fare. -

Evening & Part-Time

Department of Lifelong Learning Lifelong Learning 2016 Embracing Lifelong Learning, Planning for a Better Future CHOOSING YOUR CAREER PATH IRELAND AND IT’S PEOPLE: A HISTORY Historical Figures in Ireland joinat our us information evening Tuesday 6th September 2016 5.30pm to 8.30pm Athlone Institute of Technology register Evening & Part-Time now Prospectus 2016-2017 www.ait.ie with compliments Information and Registration Evening Tuesday 6th September 2016 5.30pm to 8.30pm Welcome to Lifelong Learning at AIT With a focus on real-world engagement, AIT’s approach to teaching and learning gives students the knowledge and skills essential for career success. This professional orientation is embedded across all facilities, with programmes offered from higher certifcate through to PhD, across its departments of business, humanities, engineering and science. Connect & Discover www.ait.ie /athloneinstituteoftechnology @AthloneIT /AthloneIT 100% 99% of Lifelong 97% of Lifelong of Lifelong Learning students Learning students Learning said they received rated our service students would enough support to them as they recommend us from us as they registered as to their family decided what good to excellent and friends course to choose 95% of Lifelong 70% of Lifelong 90% of Lifelong Learning Learning students Learning students students said felt they enhanced rated their entire they would their knowledge educational probably or and skills that will experience as defnitely study contribute to their good to excellent at AIT again employability 100% 100% of of Lifelong Lifelong Learning Learning students students believe state that the the Induction is fees installment brilliant, structure is necessary and excellent informative 47% of Lifelong what our Learning students choose our students say courses for work, 53% do so for about us.. -

International Visitors Guide University College Dublin

International Visitors Guide University College Dublin 1 International Visitors Guide Table of Contents Orientation ..................................................................................... 3 Practical Information ..................................................................... 4 Visas ............................................................................................. 4 Language ..................................................................................... 5 Weather ....................................................................................... 5 Currrency ..................................................................................... 5 Tipping (Gratuity) .......................................................................... 5 Emergencies ................................................................................. 5 Transport in Dublin ........................................................................ 6 Transport Apps .............................................................................. 6 Additional Information about UCD .................................................... 6 Arriving in Dublin ........................................................................... 7 Arriving by Plane ............................................................................ 7 Arriving by Train ............................................................................ 7 Traveling to UCD ............................................................................. 8 By Aircoach................................................................................... -

Greater Dublin Strategic Drainage Study Final Strategy Report ______

Greater Dublin Strategic Drainage Study Final Strategy Report __________________________________________________________________________________________ Greater Dublin Strategic Drainage Study Final Strategy Report Document Title Final Strategy Report Volume 1 – Main Report Volume 2 – Appendices Document Ref (s): GDSDS/NE02057/035C Date Edition/Rev Status Originator Checked Approved 28/05/04 A Draft N Fleming J Grant M Hand M Edger C O’Keeffe 06/08/2004 B Draft N Fleming J Grant M Hand M Edger C O’Keeffe 27/04/2005 C Final N Fleming J Grant M Hand M Edger C O’Keeffe Contracting Authority (CA) Personnel Council Area Council Name Operations Manager Office Location Project Engineer Name Telephone No. Operations Manager Name Telephone No. This report has been prepared for the Contracting Authority in accordance with the terms and conditions of appointment for the Greater Dublin Strategic Drainage Study dated 23rd May 2001. The McCarthy Hyder MCOS Joint Venture cannot accept any responsibility for any use of or reliance on the contents of this report by any third party. _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ GDSDS/NEO2057/035C April 2005 Greater Dublin Strategic Drainage Study Final Strategy Report __________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................................6 1.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................6 -

TO LET HEUSTON Retail Premises STATION

TO LET HEUSTON Retail Premises STATION RETAIL OPPORTUNITIES ret 3 UNITS 7 MILLION PASSENGERS HEUSTON RAILWAY STATION 3 prime retail units on busy railway concourse Units 1, 3 & 4 Comprising 61 sq.m, 30 sq.m & 51 sq.m, respectively CIE GROUP ROPERTY Suitable for a variety of food uses Oriel Street, Dublin 1 Contact Grace Flynn 01-7032929 [email protected] Lisa Mackey 01-7032925 [email protected] Unit 1 Lease Terms 10 year IR lease with Deed of Renunciation Users Unit 1 – Food use: Healthy offering or alternative food use e.g. salads, burritos, noodles etc. Unit 3 – Food use: Donuts/Crepes/Ice-cream Location Unit 4 – Food use: Bakery/Sandwich/Café offering Excellent opportunity to trade in Heuston Station - Submissions Ireland’s busiest Intercity railway station. Interested parties should submit the following Heuston Station links Dublin with the south, southwest information by email to [email protected] by 5pm and west, serving both Intercity and Commuter on Friday 20th July 2018. passengers with an annual footfall of 7 million. - Details on proposed use and planned fit-out of unit to include photo montages and plans, if This Station caters for services to Cork, Galway, possible. Waterford, Limerick, Westport and Kildare Commuter - Business and trading background and routes. Company/personal details. Details of financial offer to include: Heuston Station is a bustling hub with an average a. Estimated level of turnover. customer dwell time of 30 minutes. b. Basic annual rent Existing tenants include: c. Percentage of annual turnover which is subject to the basic annual rent, whichever M&S Simply Food, Supermacs, Eason, Butlers, Jump is the greater. -

Railway Accident Investigation Unit Ireland Annual Report

Railway Accident Investigation Unit Ireland Annual Report Annual Report 2011 Report number: 2012-AR2011 Published: 21/09/2012 Annual Report 2011 Document History Document History Title Annual Report 2011 Document type Annual Report Document number 2012-AR2011 Document issue date 21/09/2012 Revision Revision Summary of changes number date RAIU ii 2012-AR2011 Annual Report 2011 Foreword Foreword The Railway Accident Investigation Unit’s purpose is to independently investigate occurrences on Irish railways with a view to establishing their cause and make recommendations to prevent their recurrence or otherwise improve railway safety. Thirty five preliminary examinations were carried out in 2011, from which three full investigations were commenced. The first investigation involved a road vehicle struck at a manually operated level crossing being worked by members of the public. The second investigation involved a runaway locomotive. And the third related to an axle journal bearing failure on a locomotive. The Railway Accident Investigation Unit published seven investigations reports in 2011 relating to occurrences that took place in 2010. These related to: four level crossing accidents, two of which were serious accidents; two derailments; and an equipment failure on a train. A total of seventeen new safety recommendations were issued in 2011. The focus of the safety recommendations was: the effective implementation of safety controls; improvements to risk management systems; implementing effective communication procedures; and the management of risk at user worked level crossings. Seventy seven safety recommendations have been issued in total up to the end of 2011, including fourteen issued by the Railway Safety Commission in advance of the appointment of a Chief Investigator for the Railway Accident Investigation Unit in 2007. -

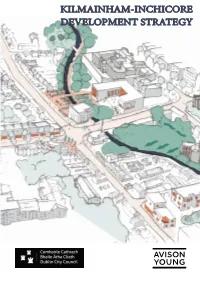

KILMAINHAM-INCHICORE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY Contents

KILMAINHAM-INCHICORE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 4 2. THEMES 6 3. STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT 16 4. VISION 24 5. REGENERATION FRAMEWORK 28 6. URBAN REGENERATION & 40 DEVELOPMENT FUND 7. DELIVERY & PARTNERSHIPS 50 APPENDIX I - SPATIAL ANALYSIS APPENDIX II - MOVEMENT ANALYSIS APPENDIX III - LINKAGE ANALYSIS APPENDIX IV - NIAH SITES / PROTECTED STRUCTURES 1. INTRODUCTION KILMAINHAM-INCHICORE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY Dublin City Council’s Kilmainham-Inchicore funding as Category “A” Projects under the Development Strategy is a non-statutory next round of the URDF later in 2021. high level study funded as a Category “B” This section sets out the basis for the Study under Call 1 of the (then) Department If Dublin City Council is successfully awarded of Housing, Planning and Local Government’s financing under the URDF it will be enabled Development Strategy, its purpose and (DHPLG) Urban Regeneration Development to undertake further detailed studies and Fund (URDF) to address opportunities for assessments of the projects before advancing what it attempts to achieve. urban regeneration and placemaking in to the planning consent process, detailed the Kilmainham-Inchicore area. The URDF design, and construction. application process is local authority led, prepared by the Executive. and determined The projects identified in the Development by the Minister for Housing and Local Strategy will be subject to a statutory Government (the Minister). The Development planning consent under the Planning and Strategy provides a framework for integrated, Development Act 2000 (as amended). All plan-led solutions, but does not authorise projects will be assessed concerning their specific projects. environmental impacts as part of a planning application. This includes compliance with The Development Strategy has been the Environmental Impact Assessment, Flood informed by the compilation of a Baseline Risk, and Habitats Directives. -

Leisure Centre Smithfield Bro 11-17.Indd

For Sale by Private Treaty On the instructions of David Potter as Receiver Leisure Centre, Block G, Smitheld, Dublin 7 (Existing tenant not aected by sale) HIGHLIGHTS • High-yielding city centre investment opportunity. • Excellent high-prole location on Smitheld Square • Substantial commercial premises let on two separate leases • Comprising of 3,179.2 sq.m. (34,221 sq.ft.) of gross oor space over three oors • Current rental income €150,000 p.a. • Opportunities to further enhance the income by active asset management FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY Leisure Centre, Block G, Smitheld, Dublin 7 LOCATION Smitheld is a historic 17th century market place in Dublin’s north inner city. It witnessed considerable regeneration in the Celtic Tiger era mainly from the available tax incentives which drove development in the late 1990s. Hotels and apartment blocks, together with retail and oce development, were all constructed on the back of this regeneration project. The predominant land use in the immediate vicinity is mixed-commercial and residential in nature. Adjoining occupiers include The Maldron Hotel, The Jameson Distillery, Fresh and Light House Cinema. The subject property is situated 200 metres north of the River Liey and Arran Quay in Dublin 7 and 350 metres west of Church Street. There is a wide selection of public transport facilities in the vicinity. The Red Luas Line from 3 Arena to Saggart & Tallaght has a stop at Smitheld. Heuston railway station is located 1km south-west of the subject property and provides intercity and commuter services to the west, south-west and south of Ireland. -

How to Get to Galway

Getting to Galway Galway is situated on the West Coast of the Republic of Ireland and may be reached by air, ferry, train, bus or car. The following air links may be of assistance www.aerlingus.ie, www.ryanair.com, and www.aerarann.ie.For international delegates we recommended the following arrangements, in order of decreasing preference: 1. Fly direct into Galway Airport. International flights directly into Galway Airport are available on www.galwayairport.com, with flights mainly from other parts of Ireland, the UK and France. 2. Fly into Dublin Airport (www.dublinairport.com) and either fly from there to Galway Airport or take a coach from Dublin Airport to Galway city. Connecting flights from Dublin Airport to Galway Airport are available through Aer Arann (www.aerarann.ie). Galway Airport is approximately 5km from Galway city centre, and both the University and hotels (names to be advised at a later date) are close to the city centre. There are taxi services from Galway Airport to Galway city: there is no bus shuttle. Car hire is also available. Dublin Airport has many international connections but is about 220km from Galway (3 hr drive). Good car hire facilities are available from Dublin Airport. Rather than flying from Dublin Airport to Galway Airport you could take a coach (or train– see below). Independent operators run dependable hourly coach services from Dublin Airport to Galway city (www.citylink.ie or www.gobus.ie), departing outside the Arrivals terminal. These coach trips take about 3 hrs. 3. Fly into Shannon Airport (www.shannonairport.com) and take a coach to Galway city. -

For Sale 18 Old Kilmainham, Kilmainham, Dublin 8

For Sale 18 Old Kilmainham, Kilmainham, Dublin 8 FILLER PICTURE RED OUTLINE FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY Property Highlights Contact • Prime redevelopment opportunity in Kilmainham, a fashionable location in Dublin 8. Sam Carthy Email: [email protected] • Site extending to approx. 0.08 ha (0.19 acre) located on Old Tel: +353 1 639 9246 Kilmainham Road. John Donegan Email: [email protected] • Zoned Objective Z1 under the Dublin City Council Development Tel: +353 1 639 9222 Plan 2016-2022. Objective Z1 is defined as ‘To protect, provide and improve residential amenities’. Cushman & Wakefield • The area is mixed in nature with commercial, residential and 164 Shelbourne Road Ballsbridge, light industrial uses. Dublin 4 Ireland • The existing buildings extend to approx. 1,127 sq m (12,134 sq Tel: +353 (0)1 639 9300 ft). cushmanwakefield.ie Location The subject property is situated on the Old Kilmainham Road, close to the junction with Brookfield Road and approx. 250m east of the junction with South Circular Road. Kilmainham is a popular south west Dublin 8 suburb. The area is a popular and well established residential location with a mix of terraced residential housing and apartment blocks. There area a number of terraced residential properties along the main road with higher density apartments situated adjacent to the property and in the surrounding area. The property is situated close to the site of the new Children’s Hospital which has a planned opening date at the end of 2021. Public transport is provided by the Red Luas line with James Luas stop and Rialto Luas stop within 600m of the site. -

Official America's Reaction to the 1916 Rising

The Wilson administration and the 1916 rising Professor Bernadette Whelan Department of History University of Limerick Chapter in Ruan O’Donnell (ed.), The impact of the 1916 Rising: Among the Nations (Dublin, 2008) Woodrow Wilson’s interest in the Irish question was shaped by many forces; his Ulster-Scots lineage, his political science background, his admiration for British Prime Minister William Gladstone’s abilities and policies including that of home rule for Ireland. In his pre-presidential and presidential years, Wilson favoured a constitutional solution to the Irish question but neither did he expect to have to deal with foreign affairs during his tenure. This article will examine firstly, Woodrow Wilson’s reaction to the radicalization of Irish nationalism with the outbreak of the rising in April 1916, secondly, how the State Department and its representatives in Ireland dealt with the outbreak on the ground and finally, it will examine the consequences of the rising for Wilson’s presidency in 1916. On the eve of the rising, world war one was in its second year as was Wilson’s neutrality policy. In this decision he had the support of the majority of nationalist Irish-Americans who were not members of Irish-American political organisations but were loyal to the Democratic Party.1 Until the outbreak of the war, the chief Irish-American political organizations, Clan na Gael and the United Irish League of America, had been declining in size but in August 1914 Clan na Gael with Joseph McGarrity as a member of its executive committee, shared the Irish Republican Brotherhood’s (IRB) view that ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity’ and it acted to realize the IRB’s plans for a rising in Ireland against British rule. -

The Week the Weather Stopped

The week the weather LIBRARY stopped ‘...in the County of Dublin’ Meteorological Records from TCD The Met Éireann Library holds meteorological records from Trinity College Dublin from 1904 to 1959. The observations were handwritten on broadsheet- sized templates, which were issued by the Meteorological Office in London. At 9 a.m. and 9 p.m. daily, readings for atmospheric pressure, temperature, wind direction, wind speed, cloud cover and rainfall (among other data) were recorded. Each template sheet also had a field for ‘Remarks’, where observers could record additional information. Generally, an observer might record a thunderstorm, a gale or another unusual weather event in this field but on one occasion, something different was recorded. ‘...observations not taken...’ Easter 1916 The image to the right shows the ‘Remarks’ made by an observer at TCD in April 1916. He writes ‘Owing to the disturbances in Dublin the observations were not taken from 24th to end of month.’ It was, of course, on the 24th of April 1916, that Patrick Pearse stood outside the G.P.O to read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. The ‘disturbances’ to which our observer referred was the start of the Easter Rising. The meteorological records did not resume again until 18th May 1916. For a period of almost four weeks, weather recordings at TCD stopped. Patrick Pearse ‘...true to its traditions’ TCD and the 1916 Rising Due to its central location in the city, Trinity College Dublin held an important strategic position in the Easter Rising. It was defended by TCD students and graduates and soldiers from nearby Dublin Castle.