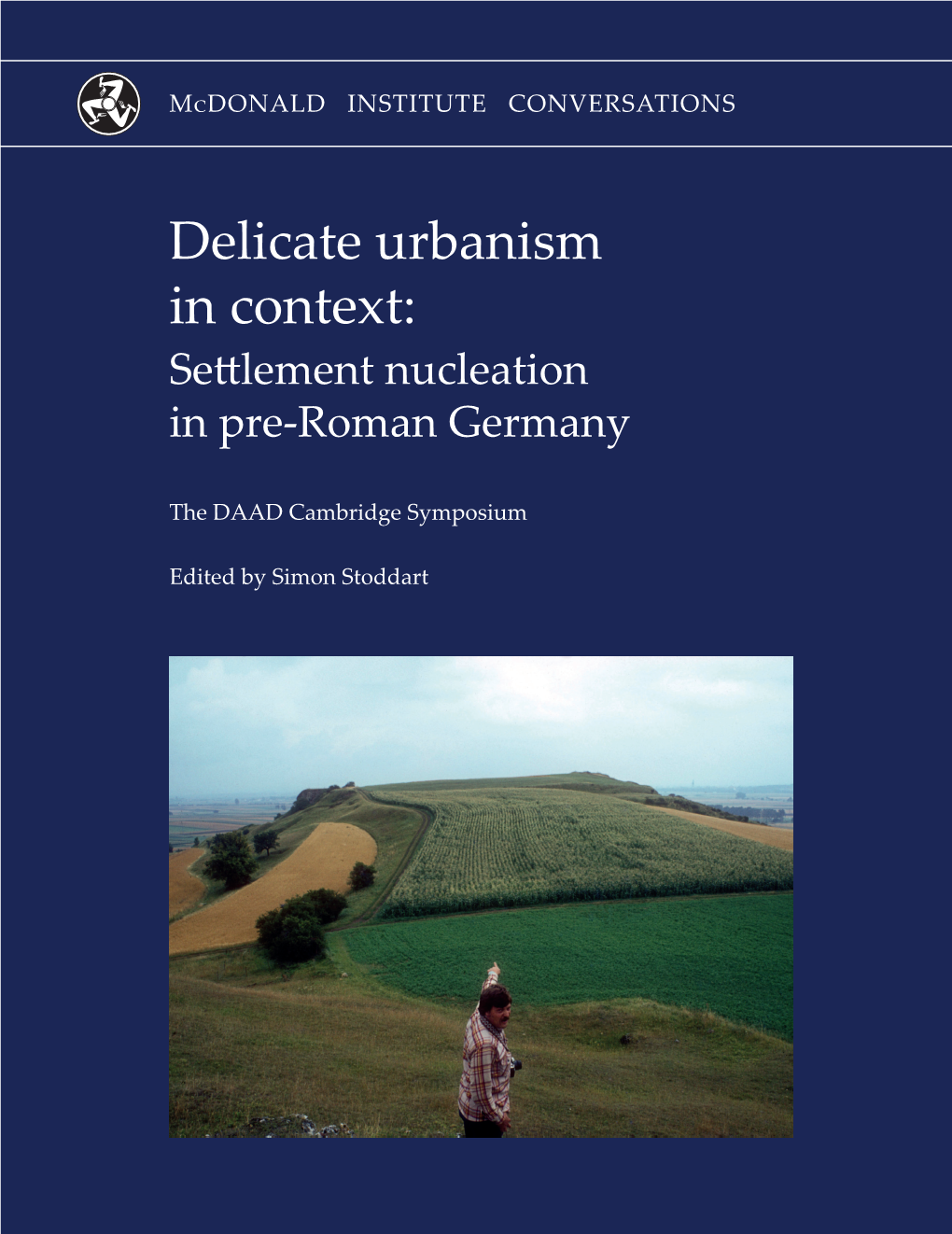

Delicate Urbanism in Context: Settlement Nucleation in Pre-Roman Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erste Verordnung Zur Änderung Des Regionalplans Der Region Landshut (13) Vom

Erste Verordnung zur Änderung des Regionalplans der Region Landshut (13) vom ................. Auf Grund von Art. 19 Abs. 1 Satz 2 Halbsatz 1 in Verbindung mit Art. 11 Abs. 5 Satz 2 des Bayerischen Landesplanungsgesetztes (BayLplG) vom 27. Dezember 2004 (GVBl S. 521, BayRS 230-1-W) erlässt der Regionale Planungsverband Landshut folgende Verordnung: § 1 Die normativen Vorgaben des Regionalplans der Region Landshut (Bekanntmachung über die Verbindlicherklärung vom 16. Oktober 1985, GVBl S. 121, ber. S 337, BayRS 230-1-U) zuletzt geändert durch Verordnung vom ............ RABl ....... S ..... werden wie folgt geändert: Das Kapitel B I Natur und Landschaft erhält nachstehende Fassung; die Karte 3 Landschaft und Erholung wird durch beiliegende Tekturkarte Landschaftliche Vorbehaltsgebiete geändert. I NATUR UND LANDSCHAFT 1 Leitbild der Landschaftsentwicklung G 1.1 Zum Schutz einer gesunden Umwelt und eines funktionsfähigen Naturhaushaltes kommt der dauerhaften Sicherung und Verbesserung der natürlichen Lebensgrund- lagen der Region besondere Bedeutung zu. G Raumbedeutsame Planungen und Maßnahmen von regionaler und überregionaler Bedeutung sind auf eine nachhaltige Leistungsfähigkeit des Naturhaushaltes abzustimmen. G 1.2 Die charakteristischen Landschaften der Region sind zu bewahren und weiterzuentwickeln. Z 1.3 Der Wald in der Region soll erhalten werden. G Die Erhaltung und Verbesserung des Zustandes und der Stabilität des Waldes, insbesondere im Raum Landshut, sind anzustreben. G Die Auwälder an Isar und Inn sind zu erhalten. G 1.4 In landwirtschaftlich intensiv genutzten Gebieten ist die Schaffung ökologischer Ausgleichsflächen anzustreben. G Natürliche und naturnahe Landschaftselemente sind als Grundlage eines regionalen Biotopverbundsystems zu erhalten und weiterzuentwickeln. G 1.5 Die Verringerung der Belastungen des Naturhaushaltes ist insbesondere im Raum Landshut anzustreben. -

Demographisches Profil Für Den Landkreis Ostallgäu

Beiträge zur Statistik Bayerns, Heft 553 Regionalisierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung für Bayern bis 2039 x Demographisches Profil für den xLandkreis Ostallgäu Hrsg. im Dezember 2020 Bestellnr. A182AB 202000 www.statistik.bayern.de/demographie Zeichenerklärung Auf- und Abrunden 0 mehr als nichts, aber weniger als die Hälfte der kleins- Im Allgemeinen ist ohne Rücksicht auf die Endsummen ten in der Tabelle nachgewiesenen Einheit auf- bzw. abgerundet worden. Deshalb können sich bei der Sum mierung von Einzelangaben geringfügige Ab- – nichts vorhanden oder keine Veränderung weichun gen zu den ausgewiesenen Endsummen ergeben. / keine Angaben, da Zahlen nicht sicher genug Bei der Aufglie derung der Gesamtheit in Prozent kann die Summe der Einzel werte wegen Rundens vom Wert 100 % · Zahlenwert unbekannt, geheimzuhalten oder nicht abweichen. Eine Abstimmung auf 100 % erfolgt im Allge- rechenbar meinen nicht. ... Angabe fällt später an X Tabellenfach gesperrt, da Aussage nicht sinnvoll ( ) Nachweis unter dem Vorbehalt, dass der Zahlenwert erhebliche Fehler aufweisen kann p vorläufiges Ergebnis r berichtigtes Ergebnis s geschätztes Ergebnis D Durchschnitt ‡ entspricht Publikationsservice Das Bayerische Landesamt für Statistik veröffentlicht jährlich über 400 Publikationen. Das aktuelle Veröffentlichungsverzeich- nis ist im Internet als Datei verfügbar, kann aber auch als Druckversion kostenlos zugesandt werden. Kostenlos Publikationsservice ist der Download der meisten Veröffentlichungen, z.B. von Alle Veröffentlichungen sind im Internet Statistischen -

Cesifo Working Paper No. 8232

8232 2020 Original Version: April 2020 This Version: December 2020 Working from Home, Wages, and Regional Inequality in the Light of Covid-19 Michael Irlacher, Michael Koch Impressum: CESifo Working Papers ISSN 2364-1428 (electronic version) Publisher and distributor: Munich Society for the Promotion of Economic Research - CESifo GmbH The international platform of Ludwigs-Maximilians University’s Center for Economic Studies and the ifo Institute Poschingerstr. 5, 81679 Munich, Germany Telephone +49 (0)89 2180-2740, Telefax +49 (0)89 2180-17845, email [email protected] Editor: Clemens Fuest https://www.cesifo.org/en/wp An electronic version of the paper may be downloaded · from the SSRN website: www.SSRN.com · from the RePEc website: www.RePEc.org · from the CESifo website: https://www.cesifo.org/en/wp CESifo Working Paper No. 8232 Working from Home, Wages, and Regional Inequality in the Light of Covid-19 Abstract We use the most recent wave of the German Qualifications and Career Survey to reveal a substantial wage premium in a Mincer regression for workers performing their job from home. The premium accounts for more than 10% and persists within narrowly defined jobs as well as after controlling for workplace characteristics. In a next step, we provide evidence on substantial regional variation in the share of jobs that can be done from home in Germany. Our analysis reveals a strong, positive relation between the share of jobs with working from home opportunities and the mean worker income in a district. Assuming that jobs with the opportunity of remote work are more crisis proof, our results suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic might affect poorer regions to a greater extent. -

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Adam R. Gustafson June 2011 © 2011 Adam R. Gustafson All Rights Reserved 2 This dissertation titled The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria by ADAM R. GUSTAFSON has been approved for the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts _______________________________________________ Dora Wilson Professor of Music _______________________________________________ Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GUSTAFSON, ADAM R., Ph.D., June 2011, Interdisciplinary Arts The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria Director of Dissertation: Dora Wilson Drawing from a number of artistic media, this dissertation is an interdisciplinary approach for understanding how artworks created under the patronage of Albrecht V were used to shape Catholic identity in Bavaria during the establishment of confessional boundaries in late sixteenth-century Europe. This study presents a methodological framework for understanding early modern patronage in which the arts are necessarily viewed as interconnected, and patronage is understood as a complex and often contradictory process that involved all elements of society. First, this study examines the legacy of arts patronage that Albrecht V inherited from his Wittelsbach predecessors and developed during his reign, from 1550-1579. Albrecht V‟s patronage is then divided into three areas: northern princely humanism, traditional religion and sociological propaganda. -

Bavarian Spiritual & Religious Highlights

Munich: The towers of the Frauenkirche are the city’s iconic landmark © DAVIS - FOTOLIA - DAVIS © Bavarian Spiritual & Religious Highlights 6 DAYS TOUR INCLUDING: WELTENBURG ABBEY ⋅ REGENSBURG ⋅ PASSAU ⋅ ALTÖTTING ⋅ KLOSTER Main Bayreuth SEEON ⋅ MUNICH Bamberg Würzburg Nuremberg Bavaria’s famed churches and other Main-Danube-Canal i Rothenburg sacred buildings are still important places o. d. Tauber Regensburg of pilgrimage and witnesses to the deeply held faith of the people of Bavaria. For Danube Weltenburg Passau instance, today, Bavaria’s monasteries Abbey have become attractive tourist landmarks. Augsburg Erding Most of them are well preserved, still Altötting Munich Marktl inhabited by their religious order and Memmingen Kloster Seeon living witness to the state’s rich past. Chiemsee Berchtesgaden Lindau Füssen Oberammergau Ettal Garmisch- Partenkirchen BAVARIA TOURISM ― www.bavaria.travel ― www.bavaria.by/travel-trade ― www.pictures.bavaria.by 02 Bavarian Spiritual & Religious Highlights DAY 1 Arrival at Munich Airport. Transfer to Weltenburg Abbey TIP Experience traditional German coffee and cake at Café in Kelheim (1 h 30 m*). Prinzess, Germany's oldest cafe. WELCOME TO WELTENBURG ABBEY, Afternoon Visit Document Neupfarrplatz GÄSTEHAUS ST. GEORG! Regensburg’s greatest archaeological excavations. The Located on the Danube Gorge, Weltenburg Abbey is cross-section goes from the Roman officers’ dwellings the oldest monastery in Bavaria and founded through the medieval Jewish quarter to an air-raid around 600 AD. Tour the abbey, Baroque Church and shelter from World War II. enjoy lunch and dinner for the day. Explore Thurn and Taxis Palace Afternoon Explore the Danube Gorge The princess of Thurn and Taxis, founder of the first Natural marvel and narrow section of the Danube valley large-scale postal service in Europe (15th century), with surrounding high limestone cliffs and caves rising turned the former monastery into a magnificent up to 70 meters. -

Via Nova Via Nova

www.pilgerweg-vianova.de Schierling · Markt Langquaid · Rohr i.NB Langquaid · Rohr i.NB · Kirchdorf Rohr i.NB · Kirchdorf · Biburg Biburg · Abensberg · Bad Gögging Abensberg · Bad Gögging · Kelheim Bad Gögging · Kelheim · Bad Abbach Kelheim · Bad Abbach · Schierling Der Barocke Markt im Markt Rohr i. NB mit 850-jähriger … im Hopfenland Hallertau Historisch – lebendig - anders …dreifach g‘sund Die Stadt im Fluss Der Kurort vor den Toren Regensburgs Großen Labertal Klostergeschichte und Abenstal 370 m ü. NN 354 m ü. NN 343 m ü. NN 338 m ü. NN 389 m ü. NN 452 m ü. NN 412 m ü. NN Abensberg – Abensberg besticht durch einen liebevoll sanierten Bad Gögging – Der familiäre Kur- und Urlaubsort in Nieder- Kelheim – Stolze Wittelsbacher Residenzstadt mit bayerischem Bad Abbach – Bereits Kelten, Römer und der deutsche Kaiser Altstadtkern. Prächtige Bürgerhäuser, das Rathaus und der bayern ist ein beliebtes Ziel für alle, die ihren Erholungsurlaub Flair: Mittelalterliche Stadttore, verspielte Renaissancefassaden, Karl V. waren von der heilenden Kraft der Schwefelquellen in Bad Langquaid – Der malerische niederbayerische Markt Langquaid Markt Rohr i.NB – Bodenständig – modern – l[i]ebenswert. Kirchdorf – Landschaftlich reizvoll gelegen und geprägt vom Maderturm prägen die historische Altstadt. Kunstliebhaber und mit dem Erlebnis bayerischer Tradition, mit regionalen Genüssen alter Kanalhafen, barocke Kirchen. Wahrzeichen der Stadt ist die Abbach begeistert. Heute überzeugt Bad Abbach mit wertvollem mit seinem schmucken historischen Wittelsbacher Marktplatz, Der Markt Rohr i.NB liegt am Beginn des Hopfenanbaugebietes Hopfenanbau. Freunde der bayerischen Bierkultur besuchen den Kuchlbau- und einem besonderen Naturerlebnis verbinden möchten. Bad von König Ludwig I. erbaute Befreiungshalle. Kelheim ist auch Naturmoor, gesundheitsaktivem Schwefel und wirkstoffreichen den barocken Bürgerhäusern und der Pfarrkirche St. -

Download Panoramakarte

Bildnachweise: Andreas Hub, Thomas Ochs Thomas Hub, Andreas Bildnachweise: Würzburg. Bonitasprint, von Farben kobaltfreien und und Druck: Klimaneutral gedruckt auf Recyclingpapier mit mineralöl mit Recyclingpapier auf gedruckt Klimaneutral Druck: 5–7 layout.de Gestaltung: kobold Gestaltung: 1 – 2 3 4 franken.de. 3. Auflage 2021, 10.000 Stück. Stück. 10.000 2021, Auflage 3. franken.de. www.flussparadies BAUNACH MAIN BAMBERG REGNITZ AURACH Impressum: Flussparadies Franken e. V., Ludwigstr. 25, 96052 Bamberg, Bamberg, 96052 25, Ludwigstr. V., e. Franken Flussparadies Impressum: R AUHE & ITZ REICHE EBRACH Raums (ELER) im Jahr 2015 Jahr im (ELER) Raums fonds für die Entwicklung des ländlichen ländlichen des Entwicklung die für fonds Landwirtschafts Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten und den Europäischen Europäischen den und Forsten und Landwirtschaft Ernährung, für Staatsministerium Bayerische das durch Gefördert und Haßberge. und die LAGs der Landkreise Forchheim, Bamberg, Lichtenfels Lichtenfels Bamberg, Forchheim, Landkreise der LAGs die Jura sowie sowie Jura Obermain und Haßberge Schweiz, Fränkische die Tourist Informationen und Naturparke Steigerwald, Steigerwald, Naturparke und Informationen Tourist die sind die Bayerischen Staatsforsten Forstbetrieb Forchheim, Forchheim, Forstbetrieb Staatsforsten Bayerischen die sind Gemeinden und den Wandervereinen. Kooperationspartner Kooperationspartner Wandervereinen. den und Gemeinden paradieses Franken e. V. zusammen mit 26 Städten und und Städten 26 mit zusammen V. e. Franken paradieses Fluss des Projekt ein ist Wanderweg Flüsse Der Sieben Der Hochwasser im Itzgrund I Thomas Ochs Naturnaher Main | Andreas Hub Bambergs Obere Brücke mit dem Alten Rathaus | Thomas Ochs Die Regnitz bei Seußling | Thomas Ochs Durch den Wiesengrund bei Pettstadt I Andreas Hub PARTNER PARTNER DIE GEHEIMNISVOLLEN DER DYNAMISCHE DIE SCHÖNE AM WASSER DIE FLIESSENDE DIE GLITZERNDEN am Rande des Steigerwalds zurück nach Bamberg. -

Successful Small-Scale Household Relocation After a Millennial Flood Event in Simbach, Germany 2016

water Article Successful Small-Scale Household Relocation after a Millennial Flood Event in Simbach, Germany 2016 Barbara Mayr *, Thomas Thaler and Johannes Hübl Institute of Mountain Risk Engineering, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Gregor-Mendel-Straße 33, 1180 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] (T.T.); [email protected] (J.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 October 2019; Accepted: 28 December 2019; Published: 4 January 2020 Abstract: International and national laws promote stakeholder collaboration and the inclusion of the community in flood risk management (FRM). Currently, relocation as a mitigation strategy against river floods in Central Europe is rarely applied. FRM needs sufficient preparation and engagement for successful implementation of household relocation. This case study deals with the extreme flood event in June 2016 at the Simbach torrent in Bavaria (Germany). The focus lies on the planning process of structural flood defense measures and the small-scale relocation of 11 households. The adaptive planning process started right after the damaging event and was executed in collaboration with authorities and stakeholders of various levels and disciplines while at the same time including the local citizens. Residents were informed early, and personal communication, as well as trust in actors, enhanced the acceptance of decisions. Although technical knowledge was shared and concerns discussed, resident participation in the planning process was restricted. However, the given pre-conditions were found beneficial. In addition, a compensation payment contributed to a successful process. Thus, the study illustrates a positive image of the implementation of the alleviation scheme. Furthermore, preliminary planning activities and precautionary behavior (e.g., natural hazard insurance) were noted as significant factors to enable effective integrated flood risk management (IFRM). -

ROOTED in the DARK of the EARTH: BAVARIA's PEASANT-FARMERS and the PROFIT of a MANUFACTURED PARADISE by MICHAEL F. HOWELL (U

ROOTED IN THE DARK OF THE EARTH: BAVARIA’S PEASANT-FARMERS AND THE PROFIT OF A MANUFACTURED PARADISE by MICHAEL F. HOWELL (Under the Direction of John H. Morrow, Jr.) ABSTRACT Pre-modern, agrarian communities typified Bavaria until the late-19th century. Technological innovations, the railroad being perhaps the most important, offered new possibilities for a people who had for generations identified themselves in part through their local communities and also by their labor and status as independent peasant-farmers. These exciting changes, however, increasingly undermined traditional identities with self and community through agricultural labor. In other words, by changing how or what they farmed to increasingly meet the needs of urban markets, Bavarian peasant-farmers also changed the way that they viewed the land and ultimately, how they viewed themselves ― and one another. Nineteenth- century Bavarian peasant-farmers and their changing relationship with urban markets therefore serve as a case study for the earth-shattering dangers that possibly follow when modern societies (and individuals) lose their sense of community by sacrificing their relationship with the land. INDEX WORDS: Bavaria, Peasant-farmers, Agriculture, Modernity, Urban/Rural Economies, Rural Community ROOTED IN THE DARK OF THE EARTH: BAVARIA’S PEASANT-FARMERS AND THE PROFIT OF A MANUFACTURED PARADISE by MICHAEL F. HOWELL B.A., Tulane University, 2002 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2008 © 2008 Michael F. Howell All Rights Reserved ROOTED IN THE DARK OF THE EARTH: BAVARIA’S PEASANT-FARMERS AND THE PROFIT OF A MANUFACTURED PARADISE by MICHAEL F. -

Einrichtungen Und Dienste Für Menschen Mit Psychischer Erkrankung Und Suchterkrankung Vorwort

BEZIRK NIEDERBAYERN Sozialverwaltung SEELISCHE GESUNDHEIT Einrichtungen und Dienste für Menschen mit psychischer Erkrankung und Suchterkrankung Vorwort Eine psychische Erkrankung kann uns alle jederzeit treff en. Viele Betroff ene versuchen, ihr Leiden möglichst lange vor ihrem sozialen Umfeld zu verbergen. Schätzungen zufolge bleiben rund zwei Drittel der seelisch erkrankten Menschen unbehandelt. Dies erhöht die Wahr- scheinlichkeit einer Chronifi zierung – bis hin zur dauerhaft en seelischen Behinde- rung. In den vergangenen Jahren ist die gesellschaft liche Stigmatisierung von Menschen mit seelischer Behinderung. psychischen Erkrankungen erfreulicher- Diese Broschüre soll Menschen mit weise zurückgegangen. Gleichzeitig ist psychischer Erkrankung sowie Sucht- die Bereitschaft gestiegen, sich fachge- erkrankung und deren Angehörigen rechte Hilfe zu holen. einen Überblick über Hilfsangebote in An dieser Stelle setzt die Arbeit des Be- Niederbayern verschaff en. zirks Niederbayern als Träger der Ein- Der Bezirk Niederbayern setzt sich dafür gliederungshilfe an, der für die psychia- ein, ein engmaschiges Netz an nieder- trische und teils auch neurologische schwelligen, bedarfsgerechten und Versorgung seiner Bevölkerung zustän- wohnortnahen Hilfen zu gestalten. Als dig ist. Dazu gehören die stationäre und gesamtgesellschaft liche Aufgabe bleibt, teilstationäre Versorgung in den psychia- das Thema psychische Erkrankung bzw. trischen Kliniken und Krankenhäusern Suchterkrankung weiter aus der Tabu- des Bezirks in Mainkofen, Landshut und zone zu holen, um dazu beizutragen, Passau sowie die ambulante Betreuung dass noch mehr Menschen die Hilfen in den dazugehörigen psychiatrischen erhalten, die sie zur Genesung, zum Institutsambulanzen. Darüber hinaus Erhalt der Lebensqualität und zur übernimmt der Bezirk den überwiegen- dauerhaft en Teilhabe am gesellschaft - den Teil der Kosten der sozialpsychia- lichenlichen LebenLebben bbrauchen.rauche trischen Dienste und Suchtberatungs- stellen im Rahmen der ambulanten Eingliederungshilfe. -

Nuts-Map-DE.Pdf

GERMANY NUTS 2013 Code NUTS 1 NUTS 2 NUTS 3 DE1 BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG DE11 Stuttgart DE111 Stuttgart, Stadtkreis DE112 Böblingen DE113 Esslingen DE114 Göppingen DE115 Ludwigsburg DE116 Rems-Murr-Kreis DE117 Heilbronn, Stadtkreis DE118 Heilbronn, Landkreis DE119 Hohenlohekreis DE11A Schwäbisch Hall DE11B Main-Tauber-Kreis DE11C Heidenheim DE11D Ostalbkreis DE12 Karlsruhe DE121 Baden-Baden, Stadtkreis DE122 Karlsruhe, Stadtkreis DE123 Karlsruhe, Landkreis DE124 Rastatt DE125 Heidelberg, Stadtkreis DE126 Mannheim, Stadtkreis DE127 Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis DE128 Rhein-Neckar-Kreis DE129 Pforzheim, Stadtkreis DE12A Calw DE12B Enzkreis DE12C Freudenstadt DE13 Freiburg DE131 Freiburg im Breisgau, Stadtkreis DE132 Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald DE133 Emmendingen DE134 Ortenaukreis DE135 Rottweil DE136 Schwarzwald-Baar-Kreis DE137 Tuttlingen DE138 Konstanz DE139 Lörrach DE13A Waldshut DE14 Tübingen DE141 Reutlingen DE142 Tübingen, Landkreis DE143 Zollernalbkreis DE144 Ulm, Stadtkreis DE145 Alb-Donau-Kreis DE146 Biberach DE147 Bodenseekreis DE148 Ravensburg DE149 Sigmaringen DE2 BAYERN DE21 Oberbayern DE211 Ingolstadt, Kreisfreie Stadt DE212 München, Kreisfreie Stadt DE213 Rosenheim, Kreisfreie Stadt DE214 Altötting DE215 Berchtesgadener Land DE216 Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen DE217 Dachau DE218 Ebersberg DE219 Eichstätt DE21A Erding DE21B Freising DE21C Fürstenfeldbruck DE21D Garmisch-Partenkirchen DE21E Landsberg am Lech DE21F Miesbach DE21G Mühldorf a. Inn DE21H München, Landkreis DE21I Neuburg-Schrobenhausen DE21J Pfaffenhofen a. d. Ilm DE21K Rosenheim, Landkreis DE21L Starnberg DE21M Traunstein DE21N Weilheim-Schongau DE22 Niederbayern DE221 Landshut, Kreisfreie Stadt DE222 Passau, Kreisfreie Stadt DE223 Straubing, Kreisfreie Stadt DE224 Deggendorf DE225 Freyung-Grafenau DE226 Kelheim DE227 Landshut, Landkreis DE228 Passau, Landkreis DE229 Regen DE22A Rottal-Inn DE22B Straubing-Bogen DE22C Dingolfing-Landau DE23 Oberpfalz DE231 Amberg, Kreisfreie Stadt DE232 Regensburg, Kreisfreie Stadt DE233 Weiden i. -

Invest in Bavaria Facts and Figures

Invest in Bavaria Investors’guide Facts and Figures and Figures Facts www.invest-in-bavaria.com Invest Facts and in Bavaria Figures Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, Infrastructure, Transport and Technology Table of contents Part 1 A state and its economy 1 Bavaria: portrait of a state 2 Bavaria: its government and its people 4 Bavaria’s economy: its main features 8 Bavaria’s economy: key figures 25 International trade 32 Part 2 Learning and working 47 Primary, secondary and post-secondary education 48 Bavaria’s labor market 58 Unitized and absolute labor costs, productivity 61 Occupational co-determination and working relationships in companies 68 Days lost to illness and strikes 70 Part 3 Research and development 73 Infrastructure of innovation 74 Bavaria’s technology transfer network 82 Patenting and licensing institutions 89 Public sector support provided to private-sector R & D projects 92 Bavaria’s high-tech campaign 94 Alliance Bavaria Innovative: Bavaria’s cluster-building campaign 96 Part 4 Bavaria’s economic infrastructure 99 Bavaria’s transport infrastructure 100 Energy 117 Telecommunications 126 Part 5 Business development 127 Services available to investors in Bavaria 128 Business sites in Bavaria 130 Companies and corporate institutions: potential partners and sources of expertise 132 Incubation centers in Bavaria’s communities 133 Public-sector financial support 134 Promotion of sales outside Germany 142 Representative offices outside Germany 149 Important addresses for investors 151 Invest in Bavaria Investors’guide Part 1 Invest A state and in Bavaria its economy Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, Infrastructure, Transport and Technology Bavaria: portrait of a state Bavaria: part of Europe Bavaria is located in the heart of central Europe.