Assessment of Benefits and Problems of Mgnrega in Karamadai Block in Coimabatore District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVERNMENT of TAMIL NADU Rural Development and Panchayat

GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU Rural Development and Panchayat Raj Department District Rural Development Agency, Coimbatore. Ph: 0422 - 2301547 e-mail: [email protected] Tender Notice No. DIPR/3200/Tender/2016 dated 03.08.2016 NOTICE INVITING TENDERS 1. The Project Director, DRDA, Coimbatore District on behalf of the Governor of TamilNadu invites the item rate bids, in electronic tendering system, for construction of roads under Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana for each of the following works including their maintenance for five years from the eligible and approved contractors registered with Highways/PWD/ any other State or Central Government Engineering Departments/ undertakings/ organizations/DRDA. Package Name of the work Estimated Cost Total Period of Bid no. (Rs. Lakh) Cost Completio Security (Rs. n (in Lakh) Rupees) Constr Mainten uction ance 6 1 2 3 4 5 7 TN-02-93 Karamadai Tholampalayam 100.23 5.56 road to Billichigoundanur road in Karamadai Block 9 Months Kalaampalayam to Seeliyur in 97.90 8.37 Karamadai Block 198.13 13.93 212.06 425000 Bujankanur to Mettupalayam 70.57 3.28 road in Karamadai Block TN-02-94 9 Months Karamadai Tholampalayam road to Sellappanur road in 71.69 6.37 Karamadai Block 142.26 9.65 151.91 304000 Ooty Kothagiri MTP Sathi Gobi Erode Branch 77.91 2.88 at 59 0 Vellipalayam road in Karamadai Block TN-02-95 Lingagoundenpudur to Cheran 9 Months 60.02 3.53 Nagar in Karamadai Block Samayapuram to koduthurai 41.97 3.60 malai in Karamadai Block 179.9 10.01 189.91 380000 Vadavalli Main road to Periyapadiyanur Kovil 103.94 -

Physicochemical Analysis of Groundwater Quality of Velliangadu Area in Coimbatore District, Tamilnadu, India

Vol. 12 | No. 2 |409 - 414| April - June | 2019 ISSN: 0974-1496 | e-ISSN: 0976-0083 | CODEN: RJCABP http://www.rasayanjournal.com http://www.rasayanjournal.co.in PHYSICOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF GROUNDWATER QUALITY OF VELLIANGADU AREA IN COIMBATORE DISTRICT, TAMILNADU, INDIA K. Karthik 1,*, R. Mayildurai 1, R. Mahalakshmi 1and S. Karthikeyan 2 1Department of Science and Humanities (Chemistry Division), Kumaraguru College of Technology, Coimbatore - 641049, Tamil Nadu, India 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Kumaraguru College of Technology, Coimbatore - 641 049, Tamil Nadu, India *E-mail : [email protected] ABSTRACT The global climatic change has its impacts on the water crisis in some areas and Coimbatore is one of the places where the groundwater levels are declining every year. In the recent past, drilling of the bore-wells increased massively in search of water since most of the open wells dried up in Velliangadu area of Coimbatore district. Open well water used to be the primary source of water for irrigation purpose till last decade but more and more bore wells were drilled in search of water up to 1000 feet underground. Since the drilled bore wells were of a minimum of 300 feet and a maximum of above 1000 feet it was quite interesting to analyze the physicochemical properties of groundwater and help the farmers to gain knowledge on water quality parameters. The quality of groundwater in Velliangadu area was analyzed by determining the pH, Hardness, Alkalinity, Total Dissolved Solids, Chloride content and Electrical Conductivity. Since all the parameters were in good agreement with the standard values given by various organizations it is concluded that the groundwater quality of Velliangadu area is good. -

Chief Minister's Nutritious Me^Jl Programme^

Chief Minister’s Nutritious Me^jl Programme^ uP€0)iua^(b Quk&a >s6/rs^utLj(b €usitM s QsutaaiQth" AIM APPRAISAL 1 9 8 7 CHIEF MINISTER’S NUTRITIOUS MEAL PROGRAMME AN APPRAISAL Sy Dr. (Tmt.) RAJAMMAL P. DEVADAS, M.A., M.Sc., Ph.D.Ohio (State), D.Sc. (Madras), Director, Sri Avinashilingam Home Science College fa t Women. Coimbatore-W 043 lUBLtC (CMNM?) DEl^ARTMENt CDVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU 19 87 Natlf'tisl Sy«ttmi Unit, Instinjitt of EducatioiiAl Plrrr^?rr nj 17*B S. iAt> i a^o M^.NewI>dUbi41001€ DOC No.. ^«XX.)l. 2 - = l G. RAMACHANDRAN Sm 1|h St. George CHIEF MINISTER MADRAS-600 009 Dated 19th January 1987 FOREWORD The idea of providing whole-some food to the needy children, stemmed from my own childhood experience of poverty. When hunger haunted my home, a lady next door extended a bowl of rice gruel to us and thus saved us from cruel death. Such mtrciful women-folk elected me as the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu having great faith in me. 1 felt it lim y bounden duty to provide atleast one meal per day to the poor children in order to eliminate the suffering of their helpless mothers. Thus was born the massive nutritious noon meal programme which on date covers more than 8.5 million children through 66,000 centres spread all over the State of Tamil Nadu. ■The programme is not just to appease the hunger of the children, though it is the most important of the aims. We have to build the character of the chffdfeil in all possible ways and should see them as responsible citizens of tomorrow. -

Volume 6, Issue 2 (V) : April – June 2019

Volume 6, Issue 2 (V) ISSN 2394 - 7780 April - June 2019 International Journal of Advance and Innovative Research (Conference Special) Indian Academicians and Researchers Association www.iaraedu.com 3RD NATIONAL CONFERENCE ON APPLICATION OF MODERN MANAGEMENT THOUGHTS Organized by PG and Research Department of Management Studies Hindusthan College of Arts and Science Coimbatore March 9, 2019 Publication Partner Indian Academicians and Researcher’s Association Hindusthan College of Arts and Science Coimbatore Affiliated to Bharathiar University Approved by AICTE and Govt of Tamilnadu Accredited by NAAC An ISO Certified Institution Special Volume Editor Dr. D. Kalpana Professor PG & Research Department of Management Studies Hindusthan College of Arts and Science Coimbatore ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Chief Patron Mr. T. S. R. Khannaiyann Chairman Hindusthan Educational and Charitable Trust, Coimbatore Chairman Tmt. Sarasuwathi Khannaiyann Managing Trustee Hindusthan College and Charitable Trust, Coimbatore Patrons Thiru. K. Sakthivel Trustee Administration Hindusthan Educational and Charitable Trust, Coimbatore Tmt. Priya Satishprabhu Executive Trustee and Secretary Hindusthan Educational and Charitable Trust, Coimbatore Co-Chairman Dr. A. Ponnusamy Principal Hindusthan College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Co-ordinator Dr. D. M. Navarasu Director - MBA Hindusthan College of Arts and Science Organising Secretary Dr. D. Kalpana Professor PG & Research Department of Management Studies Hindusthan College of Arts and Science Organizing Committee Mr. B. Nandhakumar Dr. K. Latha Dr. D. Suganthi Dr. D. Barani Kumar Dr. N. Pakutharivu Dr. K. Anitha Mrs. R. Shobana Dr. V. Sridhar Mr. N. J. Ravichandran ABOUT HINDUSTHAN COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE Hindusthan College of Arts and Science (Autonomous) is a constituent of Hindusthan Educational and Charitable Trust. -

A Case of Odanthurai

Research Paper Volume : 3 | Issue : 9 | September 2014 • ISSN No 2277 - 8179 Effective Leadership and People Social Science Participation towards Achieving all round KEYWORDS : Democratic Decentralization, Participatory Development and Planning at Grassroot Level, pollution-free environment, Development - A Case of Odanthurai Gram Non-Conventional Energy, 73rd constitutional Panchayat in Tamilnadu amendment Assistant Professor, Centre for Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation, National Institute of Dr. R. Chinnadurai Rural Development, Rajendra Nagar, Hyderabad – 500 030. ABSTRACT Democratic Decentralization, Participatory Development and Planning at Grassroots Level are the vital areas of concerns of the present approach of poverty reduction and sustainable development in India. This case study documented some best practices of participatory planning and implementation at gram panchayat level. Odanthurai village panchayat of Karamadai block in Coimbatore district in Tamilnadu has been given in this article as a case of success in achieving all round development, based on its success in fulfilling basic needs, education development, provision of housing, technology transfer, production of electricity and coverage of beneficiaries under government development and welfare programmes for its people. It is a worth learning experience for under- standing grass roots planning, people participation, effective leadership and transparent local administration. I. Background of the Case leadership by Mr.Shanmugam, President of the village panchay- Democratic Decentralization, Participatory Development and at, there are two primary schools, one middle school, two ma- Planning at Grassroot Level are the vital areas of concerns of the triculation schools functioning with all adequate facilities. present approach of poverty reduction and sustainable devel- opment in India. Tremendous efforts have been put in through III. -

Chapter – Iii Agro Climatic Zone Profile

CHAPTER – III AGRO CLIMATIC ZONE PROFILE This chapter portrays the Tamil Nadu economy and its environment. The features of the various Agro-climatic zones are presented in a detailed way to highlight the endowment of natural resources. This setting would help the project to corroborate with the findings and justify the same. Based on soil characteristics, rainfall distribution, irrigation pattern, cropping pattern and other ecological and social characteristics, the State Tamil Nadu has been classified into seven agro-climatic zones. The following are the seven agro-climatic zones of the State of Tamil Nadu. 1. Cauvery Delta zone 2. North Eastern zone 3. Western zone 4. North Western zone 5. High Altitude zone 6. Southern zone and 7. High Rainfall zone 1. Cauvery Delta Zone This zone includes Thanjavur district, Musiri, Tiruchirapalli, Lalgudi, Thuraiyur and Kulithalai taluks of Tiruchirapalli district, Aranthangi taluk of Pudukottai district and Chidambaram and Kattumannarkoil taluks of Cuddalore and Villupuram district. Total area of the zone is 24,943 sq.km. in which 60.2 per cent of the area i.e., 15,00,680 hectares are under cultivation. And 50.1 per cent of total area of cultivation i.e., 7,51,302 19 hectares is the irrigated area. This zone receives an annual normal rainfall of 956.3 mm. It covers the rivers ofCauvery, Vennaru, Kudamuruti, Paminiar, Arasalar and Kollidam. The major dams utilized by this zone are Mettur and Bhavanisagar. Canal irrigation, well irrigation and lake irrigation are under practice. The major crops are paddy, sugarcane, cotton, groundnut, sunflower, banana and ginger. Thanjavur district, which is known as “Rice Bowl” of Tamilnadu, comes under this zone. -

Production of Banana in Peri-Urban Areas of Coimbatore City – an Economic Analysis

Visit us - www.researchjournal.co.in DOI : 10.15740/HAS/IRJAES/8.1/43-50 International Research Journal of Agricultural Economics and Statistics Volume 8 | Issue 1 | March, 2017 | 43-50 e ISSN-2231-6434 Research Paper Production of banana in peri-urban areas of Coimbatore city – An economic analysis N. SAHAANAA, T. ALAGUMANI AND C. VELAVAN See end of the paper for ABSTRACT : In this paper, resource use efficiency and technical efficiency of banana cultivation were authors’ affiliations measured in peri-urban areas of Coimbatore city of Tamil Nadu. The study revealed that quantity of Correspondence to : nitrogen and the number of irrigations had a positive and significant influence on the yield of banana. C. VELAVAN The ratio of MVP to MFC was greater than one for nitrogen and number of irrigation indicated that the Department of Trade and Intellectual Property, under utilization of resources, hence there exists the possibility of enhancing their yield by increasing CARDS, Tamil Nadu their efficiency. The overall mean technical efficiency of banana was 0.73, which indicated the possibility Agricultural University, of increasing the yield of the crops by adopting better technology and cultivation practices. The scale COIMBATORE (T.N.) INDIA efficiency among the farmers ranged between 0.49 and 1.00 with mean scale efficiency score of 0.74. Email : [email protected]. in Further, it was found that 84.93 per cent of farms were below the optimal scale size, have the scope of increasing their scale efficiency and thereby operate at optimal scale to increase their farm productivity and income. -

PROFIT MAXIMIZATION of GOAT FARMERS in COIMBATORE DISTRICT THROUGH CONTROL of PARASITES Dr

International Journal of Science, Environment ISSN 2278-3687 (O) and Technology, Vol. 8, No 3, 2019, 731 – 734 2277-663X (P) PROFIT MAXIMIZATION OF GOAT FARMERS IN COIMBATORE DISTRICT THROUGH CONTROL OF PARASITES Dr. A. Aruljothi* and Dr. P. Nithya Veterinary University Training and Research Centre, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Tamil Nadu, India *E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Goat rearing has gained the reputation of one of the most important livestock rearing for poverty alleviation, livelihood enhancement, food and nutritional security in India. It is associated with simplicity in maintenance comparing the other livestock, especially to landless and resource poor farmers. One village was selected from each block of Coimbatore district and a total of 12 villages from all 12 blocks of Coimbatore district were covered under the study. The dung sample was collected from dull and anaemic goats and kids with poor weight gain. From the routine examination of dung samples collected from organized goat farms in Coimbatore district it was observed that the productivity loss is mainly due to the presence of ecto and endo-parasites in goats and kids. In each village dung samples were collected from 6 goats and 6 kids directly from the rectum and examined under microscope. Out of the 72 dung samples of goats (dung samples collected from 6 goats in each block and a total of 12 blocks of Coimbatore district) examined, 39 goats (54.16%) showed the presence of endo-parasites. This revealed the presence of parasite eggs of Strongyle sp. in 34 goats (87.18%) and Trichuris sp. -

Whoswho 2018.Pdf

Hindi version of the Publication is also available सत㔯मेव ज㔯ते PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA WHO’S WHO 2018 (Corrected upto November 2018) सं द, र ी㔯 स ाज㔯 त सभ ार ा भ P A A H R B LI A AM S EN JYA T OF INDIA, RA RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI © RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI http://parliamentofindia.nic.in http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL TEAM Shri D. S. Prasanna Kumar Director Smt. Vandana Singh Additional Director Smt. Asha Singh Joint Director Shri Md. Salim Ali Assistant Research Officer Shri Mohammad Saleem Assistant Research Officer PUBLISHED BY THE SECRETARY-GENERAL, RAJYA SABHA AND PRINTED BY DRV GrafIx Print, 41, Shikshak BHAwAN, INSTITUTIonal AREA, D-BLoCK JANAKPURI, NEw DELHI-110058 PREFACE TO THE THIRTY-FOURTH EDITION Rajya Sabha Secretariat has the pleasure of publishing the updated thirty- fourth edition of ‘Rajya Sabha who’s who’. Subsequent to the retirement of Members and biennial elections and bye- elections held in 2017 and 2018, information regarding bio-data of Members have been updated. The bio-data of the Members have been prepared on the basis of information received from them and edited to keep them within three pages as per the direction of the Hon’ble Chairman, Rajya Sabha, which was published in Bulletin Part-II dated May 28, 2009. The complete bio-data of all the Members are also available on the Internet at http://parliamentofindia.nic.in and http://rajyasabha.nic.in. NEW DELHI; DESH DEEPAK VERMA, December, 2018 Secretary-General, Rajya Sabha CONTENTS PAGES 1. -

Coimbatore District Covid Vaccination Details

COIMBATORE DISTRICT COVID VACCINATION DETAILS Date : 3-Sep - Tokens will be issued from 1.00 PM - Vaccinations will start by 2.00 PM - General Public will not be allowed in Special Camps Camps Covishield Covaxin Total Rural (Village Panchayat) 67 15000 0 15000 Rural (Town Panchayath) 28 5000 0 5000 Coimbatore Corporation 35 14000 1050 15050 Special Camp - Colleges 5 1070 0 1070 Specials Camp - Industries 10 6760 300 7060 Special Camps - NGO and Tribal 5 2850 500 3350 Special Camp - Schools 51 7650 2550 10200 24 * 7 Units 15 8500 1500 10000 Total 216 60830 5900 66730 Coimbatore Corporation - Vaccination Centres - Details Date : 3-Sep S.No Zone Ward No Camp Site Covishield Covaxin 1 West 6 Corporation Middle school, Edyarpalayam 400 30 2 West 7 Devangar kalyana mandapam, Edyarpalayam 400 30 3 West 10 Saibaba vidhyalaya School, Saibaba kovil 400 30 4 West 12 Coproration Kalai arangam, Ramalingam colony 400 30 5 West 19 Corporation Middle school, Veerakeralam 400 30 6 West 20 Corporation Elementary school, Seeranaickenpalayam 400 30 7 West 24 Corporation Elementary school, Better Mount pet 400 30 8 East 32 Corporation Elementary school, Cheranamnagar 400 30 9 East 35 Corporation Elementary school, RG Pudur 400 30 10 East 63 Corporation Middle school, Kallimadai 400 30 11 East 57 Corporation Middle school, Masakalipalayam 400 30 12 East 66 Corporation Elementary school, Udayampalayam 400 30 13 East 75 Corporation Elementary school, Anupperpalayam 400 30 14 East 58 Corporation Middle school, Neelikonampalayam 400 30 15 Central 80 Corporation -

Coimbatore District – Corporation Areas – COVISHIELD Vaccination Camp Details Date : 25.08.2021 Number of Sl.NO Zone Ward No School Name UPHC Name Doses

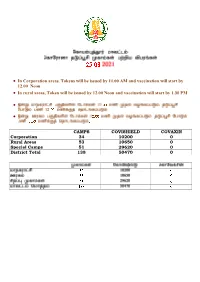

• In Corporation areas, Tokens will be issued by 11.00 AM and vaccination will start by 12.00 Noon • In rural areas, Token will be issued by 12.00 Noon and vaccination will start by 1.30 PM • • CAMPS COVISHIELD COVAXIN Corporation 34 10200 0 Rural Areas 53 10650 0 Special Camps 51 29620 0 District Total 138 50470 0 thh;L Muk;g Rfhjhu t.vz; kz;lyk; gs;spapd; bgah; vz;zpf;if vz; epiyak; 1 nkw;F muR Jtf;fg;gs;sp jr;;rd; njhl;lk;/ ,ilah;ghisak; ft[z;lk;ghisak; 300 7 2 nkw;F khefuhl;rp Jtf;fg;gs;sp/ ft[z;lk;ghisak; tlts;sp 300 8 3 nkw;F rha;ghgh tpj;ahyah gs;sp/ rha;ghgh nfhtpy; nf.nf.g[J}h; 300 10 4 nkw;F khefuhl;rp fiyau';fk;/ uhkyp';fk; efh;/ nf.nf.g[J}h; vk;.vk;.nQhk; 300 12 5 nkw;F khefuhl;rp cah;epiyg;gs;sp/ gp.vd;.g[J}h; rPuehaf;fd;ghisak; 300 15 6 nkw;F muR nky;epiyg;gs;sp fy;tPuk;ghisak; fy;tPuk;ghisak; 300 17 7 nkw;F khefuhl;rp bgz;fs; nky;epiyg;gs;sp/ Mh;.v!;.g[uk; Mh;.nf.gha; 300 24 8 fpHf;F 35 khefuhl;rp eLepiyg;gs;sp/ neU efh; tpsh';Fwpr;rp 300 9 fpHf;F 58 khefuhl;rp eLepiyg;gs;sp/ ePypf;nfhzk; ghisak; ePypnfhzk;;ghisak; 300 10 fpHf;F 32 khefuhl;rp eLepiyg;gs;sp/ tpsh';Fwpr;rp brshpghisak; 300 11 fpHf;F 33 muR cah;epiyg;gs;sp/ fhsg;gl;o e";Rz;lhg[uk; 300 12 fpHf;F 63 khefuhl;rp bgz;fs; nky;epiyg;gs;sp/ rp';fhey;Y}h; rp';fhey;Y}h; 300 13 fpHf;F 62 khefuhl;rp eLepiyg;gs;sp / fpU#;zhg[uk; cg;gpypghisak; 300 14 kj;jpak; khefuhl;rp Muk;gg;gs;sp/ Re;jnurd; ny-mt[l; v!;.vy;.vk; nQhk; 300 73 15 kj;jpak; khefuhl;rp Muk;gg;gs;sp/ mHfg;g brl;oahh; nuhL rp.o.vk; nQhk; 300 50 16 kj;jpak; khefuhl;rp eLepiyg;gs;sp / r';fD}h; ,uj;jpdg[hp 300 -

Coimbatore District Covid Vaccination Details

COIMBATORE DISTRICT COVID VACCINATION DETAILS Date : 4-Sep - Tokens will be issued from 9.00 AM - Vaccinations will start by 10.00 AM - General Public will not be allowed in Special Camps Camps Covishield Covaxin Total Rural (Village Panchayat) 64 10000 0 10000 Rural (Town Panchayath) 28 5000 0 5000 Coimbatore Corporation 32 12800 960 13760 Special Camp - Colleges 4 940 0 940 Specials Camp - Industries 10 4880 100 4980 Special Camps - NGO and Tribal 7 4800 1000 5800 Special Camp - Schools 16 4800 0 4800 24 * 7 Units 15 10000 1500 11500 Total 176 53220 3560 56780 Coimbatore Corporation - Vaccination Centres - Details Date : 4-Sep S.No Zone Ward No Camp Site Covishield Covaxin 1 West 5 Corporation Middle school, Edyarpalayam 400 30 2 West 9 Devangar kalyana mandapam, Edyarpalayam 400 30 3 West 11 Saibaba vidhyalaya School, Saibaba kovil 400 30 4 West 14 Coproration Kalai arangam, Ramalingam colony 400 30 5 West 17 Corporation Middle school, Veerakeralam 400 30 6 West 20 Corporation Elementary school, Seeranaickenpalayam 400 30 7 West 22 Corporation Elementary school, Better Mount pet 400 30 8 East 36 Corporation Elementary school, Kalapatti 400 30 9 East 56 Corporation Elementary school, Peelamedu Pudur 400 30 10 East 58 Sakkarai chettiar Kalyana mandapam 400 30 11 East 61 Corporation Primary school, Nesavalar Colony 400 30 12 East 64 Corporation Middle school, Uppilipalayam 400 30 13 East 69 Corporation Middle school, Ganesapuram 400 30 14 Central 25 Corporation Primary School, Devangpet 400 30 15 Central 45 Corporation Middle School,