Using Recorded Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bustersimpson-Surveyor.Pdf

BUSTER SIMPSON // SURVEYOR BUSTER SIMPSON // SURVEYOR FRYE ART MUSEUM 2013 EDITED BY SCOTT LAWRIMORE 6 Foreword 8 Acknowledgments Carol Yinghua Lu 10 A Letter to Buster Simpson Charles Mudede 14 Buster Simpson and a Philosophy of Urban Consciousness Scott Lawrimore 20 The Sky's the Limit 30 Selected Projects 86 Selected Art Master Plans and Proposals Buster Simpson and Scott Lawrimore 88 Rearview Mirror: A Conversation 100 Buster Simpson // Surveyor: Installation Views 118 List of Works 122 Artist Biography 132 Maps and Legends FOREWORD WOODMAN 1974 Seattle 6 In a letter to Buster Simpson published in this volume, renowned Chinese curator and critic Carol Yinghua Lu asks to what extent his practice is dependent on the ideological and social infrastructure of the city and the society in which he works. Her question from afar ruminates on a lack of similar practice in her own country: Is it because China lacks utopian visions associated with the hippie ethos of mid-twentieth-century America? Is it because a utilitarian mentality pervades the social and political context in China? Lu’s meditations on the nature of Buster Simpson’s artistic practice go to the heart of our understanding of his work. Is it utopian? Simpson would suggest it is not: his experience at Woodstock “made me realize that working in a more urban context might be more interesting than this utopian, return-to-nature idea” (p. 91). To understand the nature of Buster Simpson’s practice, we need to accompany him to the underbelly of the city where he has lived and worked for forty years. -

Sound Record Producers' Rights and the Problem of Sound Recording Piracy Stanislava N

Digital Commons @ Georgia Law LLM Theses and Essays Student Works and Organizations 8-1-2004 Sound Record Producers' Rights and the Problem of Sound Recording Piracy Stanislava N. Staykova University of Georgia School of Law Repository Citation Staykova, Stanislava N., "Sound Record Producers' Rights and the Problem of Sound Recording Piracy" (2004). LLM Theses and Essays. 50. https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/stu_llm/50 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works and Organizations at Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in LLM Theses and Essays by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOUND RECORD PRODUCERS’ RIGHTS AND THE PROBLEM OF SOUND RECORDING PIRACY by STANISLAVA NIKOLAEVA STAYKOVA (Under the Direction of David Shipley) ABSTRACT This paper will describe some current issues and developments that are of relevance to sound recordings protection, as they are experienced and debated in industry and among customers, as well as policy making bodies. The paper’s focus is on the historical development of sound recordings protection under United States Copyright law. In Part II, this paper will explore early federal and state law protections for sound recordings, including the Copyright Act of 1909, common law protections, and state statutes. This section also will trace the development of proposals for a federal statute granting express copyright protection for sound recordings. In Part III, this paper will examine the 1971 Sound Recording Amendment, particularly the scope of protection afforded for sound recordings. -

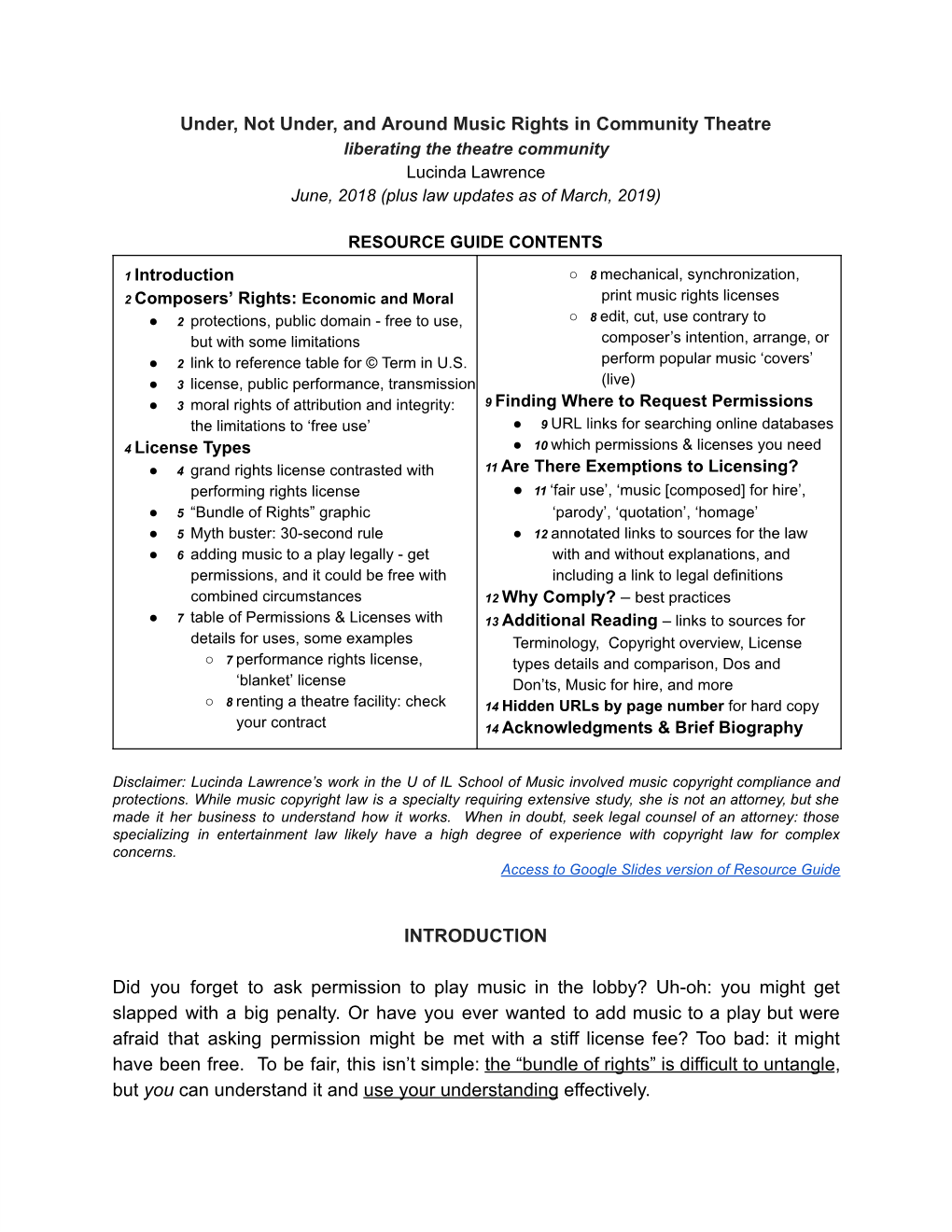

MUSIC RIGHTS PRIMER Introduction

THE COMMITTEE ON ENTERTAINMENT LAW OF THE ASSOCIATION OF THE BAR OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK January, 2003 The Committee gratefully acknowledges the contributions of prior chairpersons, Noel L. Silverman and Victoria G. Traube, and of H. Joseph Mello, the initial editor. MUSIC RIGHTS PRIMER Introduction This Primer is intended to assist lawyers who are not actively engaged in the music sub- specialty of entertainment law, but who, from time to time, may be involved with matters pertaining to that area. It is also intended for law students and non-lawyers who have an interest or involvement in the entertainment industry. We envision this Primer to be used primarily to explain the different rights that fall under the generic term “music rights”, and to delineate generally which rights are necessary for projects or product in this medium. It is not intended as a replacement for an exhaustive treatise and should not be considered a substitute for specialized legal representation required to resolve the complex issues that often arise in transactions involving music rights. Rather, it is designed to highlight issues and to provide the basic understanding of the foundations of a music project. Specialists in the field should be consulted when additional legal assistance is needed. They can easily be found in New York, Los Angeles and Nashville, and to a lesser extent, in other parts of the country. This Primer deals with music rights in the United States only. While many of the principles discussed below apply in other countries as well, there may be significant differences, and resolution of foreign issues is outside the scope of this Primer. -

Buster – Ein Gauner Mit Herz Phil Collins

HanseSound – Exklusiv Titel Buster – Ein Gauner mit Herz Phil Collins • Originaltitel: Buster • Produktionsjahr: 1988 • Produktionsland: Großbritannien • Darsteller: Phil Collins, Julie Walters, Larry Lamb • Regisseur: David Green • Format: Dolby Digital 5.1 (deutsch, englisch), PAL, Breitbild • Region: Region B/2 • Bildseitenformat: 1,66:1 • FSK: Freigegeben ab 12 Jahren • Bonus: englische Fassung mit 102,41 Min.(BD), Anwahl der Musikstücke. deutsche Untertitel MediaBook: DVD & Blu ray DVD: Blu ray: EAN: 4250124370893 EAN: EAN: Vö.: 18.09.2020 Vö.: Vö.: HAP: 14,85 HAP: HAP: Laufzeit:. 96,18+100,10 Laufzeit: 96,18 min. Laufzeit: 100,10 min. Das Wichtigste für den Kleinganoven Buster Edwards (Phil Collins) ist die Liebe seiner Frau June (Julie Walters, „Harry Potter“-Filmreihe). Als diese sich ein Haus wünscht, weiß Buster, dass er ein größeres Ding drehen muss. Mit einigen Kumpanen raubt er einen Postzug aus, doch der ausgetüftelte Plan für danach geht gründlich schief und Buster muss am Ende eine schwere Entscheidung treffen… Die Legende um den berühmtesten Postraub aller Zeiten aus völlig neuer Sicht, garniert mit Welthits aus der Feder von Megastar Phil Collins, der auch die Hauptrolle spielt! Es ist die Tragikomödie aus dem Jahr 1988. Die von Phil Collins gesungene Filmmusik wurde zu einem Erfolg in den Hitparaden. Der Film handelt von dem Postzugräuber Ronald Buster Edwards, von seiner Vorgeschichte, dem Raub und der Flucht nach Mexiko bis hin zur Entlassung aus dem Gefängnis. HanseSound – Exklusiv Titel Die Phil-Collins-Singles aus dem Film, A Groovy Kind of Love und Two Hearts, erreichten Platz 1 und Platz 6 in den UK Singles Charts. -

The Music We Perform: an Overview of Royalties, Rentals and Rights

The Music We Perform: An overview of royalties, rentals and rights The orchestra is tuned and on stage, the conductor enters and the music begins to a program set some time before. The orchestral music has been obtained, the program advertised and seats sold. It seems simple enough but what of the composers who created the works being performed? Why is their music sometimes for sale or sometimes only available on a rental basis. Why do our orchestras have to pay so much for one piece and not for another? Why should we have to deal with a difficult publisher when we can photocopy music from another source? Composers and other creative individuals are encouraged in their endeavors by the protection they receive for their intellectual property through the Berne Convention which was incorporated as a part of the U.S. Copyright Law effective March 1, 1989. This law grants creators of "original works of authorship" such as composers, authors, poets, dramatists, choreographers and others certain exclusive rights to do and to authorize the following: 1. to reproduce the copyrighted work in copies or phonorecords; 2. to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work; 3. to distribute copies or phonorecords of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease or lending; 4. in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and motion pictures and other audiovisual works, to perform the copyrighted work publicly, and 5. in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic, or sculptural works, including the individual images of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, to display the copyrighted work publicly. -

Bmi’S Response to the Department of Justice’S June 5, 2019 Request for Public Comments Concerning the Bmi and Ascap Consent Decrees

BMI’S RESPONSE TO THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE’S JUNE 5, 2019 REQUEST FOR PUBLIC COMMENTS CONCERNING THE BMI AND ASCAP CONSENT DECREES August 9, 2019 Scott A. Edelman Stu Rosen Fiona A. Schaeffer John Coletta Atara Miller BROADCAST MUSIC, INC. MILBANK LLP 7 World Trade Center 55 Hudson Yards 250 Greenwich Street New York, NY 10001-2163 New York, NY 10007-0030 (212) 530-5000 (212) 220-3000 Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) submits these public comments in response to the request of the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice (the “DOJ”) pursuant to its review of the consent decree in United States v. BMI, Civ. No. 64-Civ-3787 (the “Decree”). The DOJ initiated this public comment period as part of its ongoing initiative to review legacy antitrust judgments. BMI believes that the Decree has become an impediment to innovation and should be substantially modified, and ultimately terminated, to remove unnecessary restrictions that do not further a legitimate public interest and constrain BMI’s ability to best serve songwriters, composers, music publishers and music users. The Decree reflects an outdated model of antitrust enforcement by regulation. It imposes an inflexible contract structure and a judicial rate-setting process that are unresponsive to market needs, impede BMI (and other music industry participants) from adapting to changes in the marketplace, stifle innovation, and are unnecessary to preserve competition. Ending the perpetual regulation of BMI and the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (“ASCAP”) (and by extension, large swaths of the music industry) is long overdue. The music licensing marketplace and the modern antitrust framework for assessing competition in that marketplace are virtually unrecognizable from those that existed when the BMI and ASCAP consent decrees were initially entered in 1941. -

The Role of Music in European Integration Discourses on Intellectual Europe

The Role of Music in European Integration Discourses on Intellectual Europe ALLEA ALLEuropean A cademies Published on behalf of ALLEA Series Editor: Günter Stock, President of ALLEA Volume 2 The Role of Music in European Integration Conciliating Eurocentrism and Multiculturalism Edited by Albrecht Riethmüller ISBN 978-3-11-047752-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-047959-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-047755-9 ISSN 2364-1398 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover: www.tagul.com Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Foreword by the Series Editor There is a debate on the future of Europe that is currently in progress, and with it comes a perceived scepticism and lack of commitment towards the idea of European integration that increasingly manifests itself in politics, the media, culture and society. The question, however, remains as to what extent this report- ed scepticism truly reflects people’s opinions and feelings about Europe. We all consider it normal to cross borders within Europe, often while using the same money, as well as to take part in exchange programmes, invest in enterprises across Europe and appeal to European institutions if national regulations, for example, do not meet our expectations. -

US Copyright Law After GATT

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 16 Number 1 Article 1 6-1-1995 U.S. Copyright Law After GATT: Why a New Chapter Eleven Means Bankruptcy fo Bootleggers Jerry D. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jerry D. Brown, U.S. Copyright Law After GATT: Why a New Chapter Eleven Means Bankruptcy fo Bootleggers, 16 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 1 (1995). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol16/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW AFTER GATT: WHY A NEW CHAPTER ELEVEN MEANS BANKRUPTCY FOR BOOTLEGGERS Jerry D. Brown* "I am a bootlegger; bootleggin' ain't no good no more." -Blind Teddy Darby' I. INTRODUCTION On December 8, 1994, President Clinton signed into law House Bill 5110, the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) Implementation Act of 1994 . By passing the GATT Implementation Act before the end of 1994, the United States joined 123 countries in forming the World Trade Organization ("WTO"). The WTO is a multilateral trade organization established by GATT 1994, wherein member countries consent to minimum standards of rights, protection and trade regulation. Complying with these standards required the United States to amend existing law in several areas concerning trade and commerce, including areas that regulate intellectual property rights.' * B.A., University of Oklahoma, 1992; J.D., Oklahoma City University School of Law, 1995. -

SING Written by Garth Jennings Illumination

SING Written by Garth Jennings Illumination Entertainment 2230 Broadway, Santa Monica, CA 90404, United States (310) 593-8800 THIS MATERIAL IS THE PROPERTY OF ILLUMINATION ENTERTAINMENT AND IS INTENDED AND RESTRICTED SOLELY FOR ILLUMINATION PERSONNEL. DISTRIBUTION OR DISCLOSURE OF THIS MATERIAL TO UNAUTHORIZED PERSONS IS PROHIBITED. THE SALE, DISPLAY, COPYING OR REPRODUCTION OF THIS MATERIAL FOR ANY REASON IN ANY FORM, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO DIGITAL OR NEW MEDIA, IS ALSO PROHIBITED. 1 EXT. SKY - NIGHT 1 The sound of an orchestra tuning up. Tilt down from twinkling stars to reveal the most beautiful old theatre in a street heaving with life... ...But not human life. This is a city inhabited entirely by animals. We glide under the illuminated marquee and through the doors into a grand foyer, where the very last patrons hurry to their seats... 2 INT. THEATRE - CONTINUOUS 2 The ornate house lights dim... Voices hushed. The music starts. The orchestra is loud and dramatic. BACKSTAGE: A lever is pulled... A sandbag drops from the rafters... STAGE MANAGER Places, everyone! A stage light turns on and points towards the stage. A MONKEY stands in the wings and pulls tightly on a rope. The Curtain opens, revealing a stage set resembling an enchanted wood. FROM THE WINGS we see the back of a FEMALE SHEEP (NANA NOODLEMAN) in a stunning purple dress and a tiara waiting to go on stage. STAGE HANDS adjust the train of her gown. Nana’s shoulders rise and fall as she takes a last breath before stepping out. As NANA raises her face into the spotlight she sings “Golden Slumbers” by the Beatles. -

View Song List

Piano Bar Song List 1 100 Years - Five For Fighting 2 1999 - Prince 3 3am - Matchbox 20 4 500 Miles - The Proclaimers 5 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin' Groovy) - Simon & Garfunkel 6 867-5309 (Jenny) - Tommy Tutone 7 A Groovy Kind Of Love - Phil Collins 8 A Whiter Shade Of Pale - Procol Harum 9 Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) - Nine Days 10 Africa - Toto 11 Afterglow - Genesis 12 Against All Odds - Phil Collins 13 Ain't That A Shame - Fats Domino 14 Ain't Too Proud To Beg - The Temptations 15 All About That Bass - Meghan Trainor 16 All Apologies - Nirvana 17 All For You - Sister Hazel 18 All I Need Is A Miracle - Mike & The Mechanics 19 All I Want - Toad The Wet Sprocket 20 All Of Me - John Legend 21 All Shook Up - Elvis Presley 22 All Star - Smash Mouth 23 All Summer Long - Kid Rock 24 All The Small Things - Blink 182 25 Allentown - Billy Joel 26 Already Gone - Eagles 27 Always Something There To Remind Me - Naked Eyes 28 America - Neil Diamond 29 American Pie - Don McLean 30 Amie - Pure Prairie League 31 Angel Eyes - Jeff Healey Band 32 Another Brick In The Wall - Pink Floyd 33 Another Day In Paradise - Phil Collins 34 Another Saturday Night - Sam Cooke 35 Ants Marching - Dave Matthews Band 36 Any Way You Want It - Journey 37 Are You Gonna Be My Girl? - Jet 38 At Last - Etta James 39 At The Hop - Danny & The Juniors 40 At This Moment - Billy Vera & The Beaters 41 Authority Song - John Mellencamp 42 Baba O'Riley - The Who 43 Back In The High Life - Steve Winwood 44 Back In The U.S.S.R. -

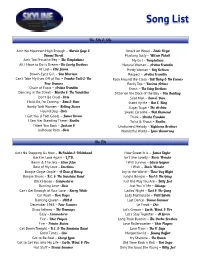

New Song List.Pages

Song List Te 50s & 60s Ain’t No Mountain High Enough – Marvin Gaye & Knock on Wood – Eddie Floyd Tammi Terrell Mustang Sally – Wilson Pickett Ain’t Too Proud to Beg – Te Temptations My Girl – Temptations All I Have to Do Is Dream - Te Everly Brothers Natural Woman – Aretha Franklin At Last – Etta Jame Pretty Woman – Roy Orbion Brown-Eyed Girl – Van Morrion Respect – Aretha Franklin Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You – Frankie Valli & Te Rock Around the Clock - Bill Haley & Hi Comets Four Seaons Rocky Top – Various Artits Chain of Fools – Aretha Franklin Shout – Te Isley Brothers Dancing in the Street – Martha & Te Vandella Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay – Oti Redding Don’t Be Cruel - Elvi Soul Man – Sam & Dave Hold On, I’m Coming – Sam & Dave Stand by Me – Ben E. King Honky Tonk Women – Rolling Stone Sugar, Sugar - Te Archie Hound Dog - Elvi Sweet Caroline – Neil Diamond I Got You (I Feel Good) – Jame Brown Think – Aretha Franklin I Saw Her Standing There - Beatle Twist & Shout – Beatle I Want You Back – Jackson 5 Unchained Melody – Righteous Brothers Jailhouse Rock - Elvi Wonderful World – Loui Armstrong Te 70s Ain’t No Stopping Us Now – McFadden & Whitehead How Sweet It Is – Jame Taylor Back in Love Again – L.T.D. Isn’t She Lovely – Stevie Wonder Benni & The Jets – Elton John I Will Survive – Gloria Gaynor Best of My Love – Emotions I Wish – Stevie Wonder Boogie Oogie Oogie – A Tate of Honey Joy to the World – Tree Dog Night Boogie Shoes – K.C. & Te Sunshine Band Jungle Boogie – Kool & Te Gang Brick House – Commodore Just the Way You Are – Billy Joel Burning Love - Elvi Just You ‘n’ Me – Chicago Can’t Get Enough of Your Love – Barry White Ladies’ Night – Kool & Te Gang Car Wash – Roe Royce Lady Marmalade – Patti Labelle Dancing Queen – ABBA Last Dance - Donna Summer December 1963 – Four Seaons Le Freak – Chic Disco Inferno – Te Trammps Let’s Groove – Earth, Wind, & Fire Easy – Commodore Let’s Stay Together – Al Green Fire – Ohio Players Long Train Runnin’ – Te Doobie Brothers Fire – Pointer Siters Love Rollercoaster – Ohio Players Get Down Tonight – K.C. -

Music Rights and Permissions Checklist INTRODUCTION These

Music Rights and Permissions Checklist INTRODUCTION These guidelines have been issued by the MPA at the request of the ABO and are designed to aid understanding of the necessary rights, clearances and permissions needed when dealing with copyright in published musical works. The guidelines also clarify from whom licences can be obtained with the aim of avoiding misunderstandings and giving clarity for users. They do not however deal with the licences and permissions required in relation to recording rights and performers’ rights. The guidelines supplement both the Guidelines for Practice in Professional Music Hire (Revised edition 2010) and the Code of Fair Practice (Revised edition 2012). Any instance of usage not covered in these guidelines should be referred to the relevant publisher or rights holder directly. TERMINOLOGY AND DEFINITIONS A basic awareness of the terminology involved when dealing with music publishing rights will assist users in understanding the various licences available and what is most suitable for their needs. Copyright Copyright is the mechanism by which creators and publishers give permission to use their work, and are paid for their work. Usually this is through the grant of a licence, which gives the user permission to use the creator’s work and sets out the terms under which they are permitted to do so. Obtaining a licence is sometimes referred to as “clearing rights”. In the UK and most of Europe, musical works remain in copyright for 70 years after the death of the last surviving creator, after which they are said to enter the “public domain”. Creators include not only the composer, but also the librettist, arranger, translator or text author (poet or literary author) for example.