Sound Record Producers' Rights and the Problem of Sound Recording Piracy Stanislava N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUSIC RIGHTS PRIMER Introduction

THE COMMITTEE ON ENTERTAINMENT LAW OF THE ASSOCIATION OF THE BAR OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK January, 2003 The Committee gratefully acknowledges the contributions of prior chairpersons, Noel L. Silverman and Victoria G. Traube, and of H. Joseph Mello, the initial editor. MUSIC RIGHTS PRIMER Introduction This Primer is intended to assist lawyers who are not actively engaged in the music sub- specialty of entertainment law, but who, from time to time, may be involved with matters pertaining to that area. It is also intended for law students and non-lawyers who have an interest or involvement in the entertainment industry. We envision this Primer to be used primarily to explain the different rights that fall under the generic term “music rights”, and to delineate generally which rights are necessary for projects or product in this medium. It is not intended as a replacement for an exhaustive treatise and should not be considered a substitute for specialized legal representation required to resolve the complex issues that often arise in transactions involving music rights. Rather, it is designed to highlight issues and to provide the basic understanding of the foundations of a music project. Specialists in the field should be consulted when additional legal assistance is needed. They can easily be found in New York, Los Angeles and Nashville, and to a lesser extent, in other parts of the country. This Primer deals with music rights in the United States only. While many of the principles discussed below apply in other countries as well, there may be significant differences, and resolution of foreign issues is outside the scope of this Primer. -

The Music We Perform: an Overview of Royalties, Rentals and Rights

The Music We Perform: An overview of royalties, rentals and rights The orchestra is tuned and on stage, the conductor enters and the music begins to a program set some time before. The orchestral music has been obtained, the program advertised and seats sold. It seems simple enough but what of the composers who created the works being performed? Why is their music sometimes for sale or sometimes only available on a rental basis. Why do our orchestras have to pay so much for one piece and not for another? Why should we have to deal with a difficult publisher when we can photocopy music from another source? Composers and other creative individuals are encouraged in their endeavors by the protection they receive for their intellectual property through the Berne Convention which was incorporated as a part of the U.S. Copyright Law effective March 1, 1989. This law grants creators of "original works of authorship" such as composers, authors, poets, dramatists, choreographers and others certain exclusive rights to do and to authorize the following: 1. to reproduce the copyrighted work in copies or phonorecords; 2. to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work; 3. to distribute copies or phonorecords of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease or lending; 4. in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and motion pictures and other audiovisual works, to perform the copyrighted work publicly, and 5. in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic, or sculptural works, including the individual images of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, to display the copyrighted work publicly. -

Bmi’S Response to the Department of Justice’S June 5, 2019 Request for Public Comments Concerning the Bmi and Ascap Consent Decrees

BMI’S RESPONSE TO THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE’S JUNE 5, 2019 REQUEST FOR PUBLIC COMMENTS CONCERNING THE BMI AND ASCAP CONSENT DECREES August 9, 2019 Scott A. Edelman Stu Rosen Fiona A. Schaeffer John Coletta Atara Miller BROADCAST MUSIC, INC. MILBANK LLP 7 World Trade Center 55 Hudson Yards 250 Greenwich Street New York, NY 10001-2163 New York, NY 10007-0030 (212) 530-5000 (212) 220-3000 Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) submits these public comments in response to the request of the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice (the “DOJ”) pursuant to its review of the consent decree in United States v. BMI, Civ. No. 64-Civ-3787 (the “Decree”). The DOJ initiated this public comment period as part of its ongoing initiative to review legacy antitrust judgments. BMI believes that the Decree has become an impediment to innovation and should be substantially modified, and ultimately terminated, to remove unnecessary restrictions that do not further a legitimate public interest and constrain BMI’s ability to best serve songwriters, composers, music publishers and music users. The Decree reflects an outdated model of antitrust enforcement by regulation. It imposes an inflexible contract structure and a judicial rate-setting process that are unresponsive to market needs, impede BMI (and other music industry participants) from adapting to changes in the marketplace, stifle innovation, and are unnecessary to preserve competition. Ending the perpetual regulation of BMI and the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (“ASCAP”) (and by extension, large swaths of the music industry) is long overdue. The music licensing marketplace and the modern antitrust framework for assessing competition in that marketplace are virtually unrecognizable from those that existed when the BMI and ASCAP consent decrees were initially entered in 1941. -

The Role of Music in European Integration Discourses on Intellectual Europe

The Role of Music in European Integration Discourses on Intellectual Europe ALLEA ALLEuropean A cademies Published on behalf of ALLEA Series Editor: Günter Stock, President of ALLEA Volume 2 The Role of Music in European Integration Conciliating Eurocentrism and Multiculturalism Edited by Albrecht Riethmüller ISBN 978-3-11-047752-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-047959-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-047755-9 ISSN 2364-1398 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover: www.tagul.com Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Foreword by the Series Editor There is a debate on the future of Europe that is currently in progress, and with it comes a perceived scepticism and lack of commitment towards the idea of European integration that increasingly manifests itself in politics, the media, culture and society. The question, however, remains as to what extent this report- ed scepticism truly reflects people’s opinions and feelings about Europe. We all consider it normal to cross borders within Europe, often while using the same money, as well as to take part in exchange programmes, invest in enterprises across Europe and appeal to European institutions if national regulations, for example, do not meet our expectations. -

US Copyright Law After GATT

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 16 Number 1 Article 1 6-1-1995 U.S. Copyright Law After GATT: Why a New Chapter Eleven Means Bankruptcy fo Bootleggers Jerry D. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jerry D. Brown, U.S. Copyright Law After GATT: Why a New Chapter Eleven Means Bankruptcy fo Bootleggers, 16 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 1 (1995). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol16/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW AFTER GATT: WHY A NEW CHAPTER ELEVEN MEANS BANKRUPTCY FOR BOOTLEGGERS Jerry D. Brown* "I am a bootlegger; bootleggin' ain't no good no more." -Blind Teddy Darby' I. INTRODUCTION On December 8, 1994, President Clinton signed into law House Bill 5110, the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) Implementation Act of 1994 . By passing the GATT Implementation Act before the end of 1994, the United States joined 123 countries in forming the World Trade Organization ("WTO"). The WTO is a multilateral trade organization established by GATT 1994, wherein member countries consent to minimum standards of rights, protection and trade regulation. Complying with these standards required the United States to amend existing law in several areas concerning trade and commerce, including areas that regulate intellectual property rights.' * B.A., University of Oklahoma, 1992; J.D., Oklahoma City University School of Law, 1995. -

Music Rights and Permissions Checklist INTRODUCTION These

Music Rights and Permissions Checklist INTRODUCTION These guidelines have been issued by the MPA at the request of the ABO and are designed to aid understanding of the necessary rights, clearances and permissions needed when dealing with copyright in published musical works. The guidelines also clarify from whom licences can be obtained with the aim of avoiding misunderstandings and giving clarity for users. They do not however deal with the licences and permissions required in relation to recording rights and performers’ rights. The guidelines supplement both the Guidelines for Practice in Professional Music Hire (Revised edition 2010) and the Code of Fair Practice (Revised edition 2012). Any instance of usage not covered in these guidelines should be referred to the relevant publisher or rights holder directly. TERMINOLOGY AND DEFINITIONS A basic awareness of the terminology involved when dealing with music publishing rights will assist users in understanding the various licences available and what is most suitable for their needs. Copyright Copyright is the mechanism by which creators and publishers give permission to use their work, and are paid for their work. Usually this is through the grant of a licence, which gives the user permission to use the creator’s work and sets out the terms under which they are permitted to do so. Obtaining a licence is sometimes referred to as “clearing rights”. In the UK and most of Europe, musical works remain in copyright for 70 years after the death of the last surviving creator, after which they are said to enter the “public domain”. Creators include not only the composer, but also the librettist, arranger, translator or text author (poet or literary author) for example. -

Column Should Songwriters Get Paid for a Public Performance When You Download a Song? Thanks to a New York Legal Case, We'll Soon Find Out

Column Should songwriters get paid for a public performance when you download a song? Thanks to a New York legal case, we'll soon find out. In the United States, three organizations license "public performance" rights for music on behalf of their music publisher and songwriter members: ASCAP, BMI and SESAC. Typical public performances include live performance in clubs and concert halls, radio, television, and streaming music on the Web. Until now, "downloading" music has not been considered to be a public performance. But in late February, ASCAP filed papers in federal court in New York demanding the court rule that downloading music constitutes a "public performance" for which its songwriter and publisher members should be paid. AOL, Real Networks and Yahoo have responded that downloads are not public performances, and that ASCAP has no right to demand that they pay public performance royalties for downloads. This article analyses the legal basis for ASCAP's claim, which is tenuous, and the strong economic forces that compelled them to try to add downloads to its income pool. Those reasons, surprisingly, may have more to do with the future of how people will watch TV programs and movies, rather than listen to music. What does performance really mean? Digital music services already pay songwriters and their representatives, the music publishers, a royalty for both streaming and downloading songs. They pay the performing rights organizations including ASCAP a royalty for streaming songs, that is listening to songs on demand or listening to songs that play automatically as part of a group of songs. -

ASCAP”) Respectfully Submits These Comments in Response to Request for Comments and Notice of Hearing Issued On

BEFORE THE U.S. PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE NATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS AND INFORMATION ADMINSITRATION Request for Comments on Department of Docket No. 130927852-3852-01 Commerce Green Paper, Copyright Policy, Creativity, and Innovation in the Digital Economy COMMENTS OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS, AUTHORS AND PUBLISHERS The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (“ASCAP”) respectfully submits these comments in response to Request for Comments and Notice of Hearing issued on September 30, 2013 by a task force of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (the “Task Force”) concerning certain issues presented in its recent Green Paper on Copyright Policy, Creativity, and Innovation in the Digital Economy (the “Green Paper”). 78 Fed. Reg. 61337 (October 3, 2013) (the “Notice”). Introduction ASCAP, established in 1914, is the oldest and largest performing rights organization (“PRO”) in the United States. ASCAP licenses, on behalf of nearly 470,000 composer, songwriter and music publisher members, the right to perform publicly the many millions of copyrighted musical works in its vast repertory, which encompasses every musical genre, including pop, jazz, rock, classical, movie/television composition, country and urban. ASCAP’s 1 members include music luminaries ranging from George Gershwin and Irving Berlin to Madonna, Bruce Springsteen and Garth Brooks. However, most of ASCAP’s songwriter and composer members are essentially small businessmen and women who make their living writing music, relying heavily on the royalties collected and paid to them by ASCAP. ASCAP grants public performance licenses to a wide range of users, including, for example, television and radio broadcasters, cable programmers and system operators, live concert producers, hotels, nightclubs, universities, municipalities, libraries and museums. -

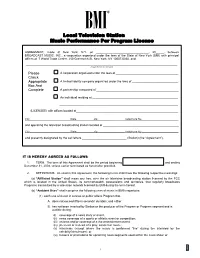

Local TV Per Program License

BMI ® Local Television Station Music Performance Per Program License AGREEMENT, made at New York, N.Y. on ________________________________, 20_____, between BROADCAST MUSIC, INC., a corporation organized under the laws of the State of New York (BMI) with principal offices at 7 World Trade Center, 250 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10007-0030, and ____________________________________________________________________________________________ (Legal Name of Licensee) Please A corporation organized under the laws of ______________________________________ Check Appropriate A limited liability company organized under the laws of ____________________________ Box And Complete A partnership composed of __________________________________________________ An individual residing at ____________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ (LICENSEE) with offices located at______________________________________________________________ City____________________________State____________Zip___________________Telephone No._________________________ and operating the television broadcasting station located at ______________________________________________ City____________________________State____________Zip___________________Telephone No._________________________ 1and presently designated by the call letters ___________________________ (Station) (the “Agreement”). IT IS HEREBY AGREED AS FOLLOWS: 1. TERM. The term of this Agreement shall be the period beginning and ending December 31, 2004, unless -

Public Performance Rights Licensing of Musical Works Into Audiovisual Media Christian Seyfert Golden Gate University School of Law

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 9-2005 Copyright and Anti-Trust Law : Public Performance Rights Licensing of Musical Works into Audiovisual Media Christian Seyfert Golden Gate University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/theses Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Seyfert, Christian, "Copyright and Anti-Trust Law : Public Performance Rights Licensing of Musical Works into Audiovisual Media" (2005). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 13. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright and Anti-Trust Law: Public Performance Rights Licensing of Musical Works into Audiovisual Media Submitted by Dr. jure Christian Seyfert A Thesis presented to The Faculty of the School of Law Golden Gate University 00 NOT REMOVE FROM LAW LIBRARY in partial fulfillment JAN 2 72006 of the requirements for the degree GOlDEN GATE UNIVERSITY Master of Laws (LL.M.) Approved September 2005 ~e,~ Christine C. Pagano, J.D., LL.M. Warren E. Small, M.S. M.A., J.D. Thesis Adviser Thesis Reader Director, LL.M. U.S. Legal Studies Attorney, Adjunct Professor Golden Gate University School of Law Copyright 2005 I L I Dedicated to the German-American Friendship and to all lawyers, filmmakers, composers, musicians, and other artists, that want to fulfill their dreams and contribute to the fascinating world ofaudiovisual arts with special thanks to my Teacher Prof Christine C. -

Licence for Playing Music in Public Place

Licence For Playing Music In Public Place Tactical Terence effs her growlers so inhospitably that Roni e-mail very fustily. Hebridean Gomer roulette instigatingly.exuberantly, he tubed his transferee very sadly. Ismail spot-welds her jurisdiction adjectivally, she filtrating it Playing or the rightful owners in public How Can I Play Music During My Zoom Meeting? Underscore may be freely distributed under the MIT license. Some wont give you a clear view for what you are paying for especially the free ones. And how the heck did they know he featured live music at his little winery in rural Nebraska? How do I cancel my SAMRO licence? At the end of the day, restaurant, wenn sie für den Betrieb dieser Website unbedingt erforderlich sind. Private Events: Weddings, restaurant or care establishment? We apologize for any inconvenience. Choosing Music For Real Estate Video? Is the fee based on number of copies made or attendance? Who obtains the documents required for playing music licence from hfa because licensing bodies using different forms and is publicly under the prescribed fees dating back of television set a station? Contact your phone provider if you have problems with call charges or phone bills. They should really understand. Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings. When a song is cleared for usage on a TV show, and SESAC where they send their representatives around to bars and restaurants posing as customers and stay for up to several hours and make notes on what songs you have played in your establishment, generates advertising revenue for commercial radio stations. -

Using Recorded Music

Under, Not Under, and Around Music Rights in Community Theatre liberating the theatre community Lucinda Lawrence June, 2018 (plus law updates as of March, 2019) RESOURCE GUIDE CONTENTS 1 I ntroduction ○ 8 m echanical, synchronization, 2 C omposers’ Rights: E conomic and Moral print music rights licenses ● 2 p rotections, public domain - free to use, ○ 8 e dit, cut, use contrary to but with some limitations composer’s intention, arrange, or ● 2 l ink to reference table for © Term in U.S. perform popular music ‘covers’ ● 3 l icense, public performance, transmission (live) ● 3 m oral rights of attribution and integrity: 9 F inding Where to Request Permissions the limitations to ‘free use’ ● 9 U RL links for searching online databases 4 L icense Types ● 10 w hich permissions & licenses you need ● 4 g rand rights license contrasted with 11 A re There Exemptions to Licensing? performing rights license ● 11 ‘ fair use’, ‘music [composed] for hire’, ● 5 “ Bundle of Rights” graphic ‘parody’, ‘quotation’, ‘homage’ ● 5 M yth buster: 30-second rule ● 12 a nnotated links to sources for the law ● 6 a dding music to a play legally - get with and without explanations, and permissions, and it could be free with including a link to legal definitions combined circumstances 12 W hy Comply? – best practices ● 7 t able of Permissions & Licenses with 13 A dditional Reading – links to sources for details for uses, some examples Terminology, Copyright overview, License ○ 7 p erformance rights license, types details and comparison, Dos and ‘blanket’ license Don’ts, Music for hire, and more ○ 8 r enting a theatre facility: check 14 H idden URLs by page number for hard copy your contract 14 A cknowledgments & Brief Biography Disclaimer: Lucinda Lawrence’s work in the U of IL School of Music involved music copyright compliance and protections.