Apple: from Garage to World's Most Valuable Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steve Wozniak Was Born in 1950 Steve Jobs in 1955, Both Attended Homestead High School, Los Altos, California

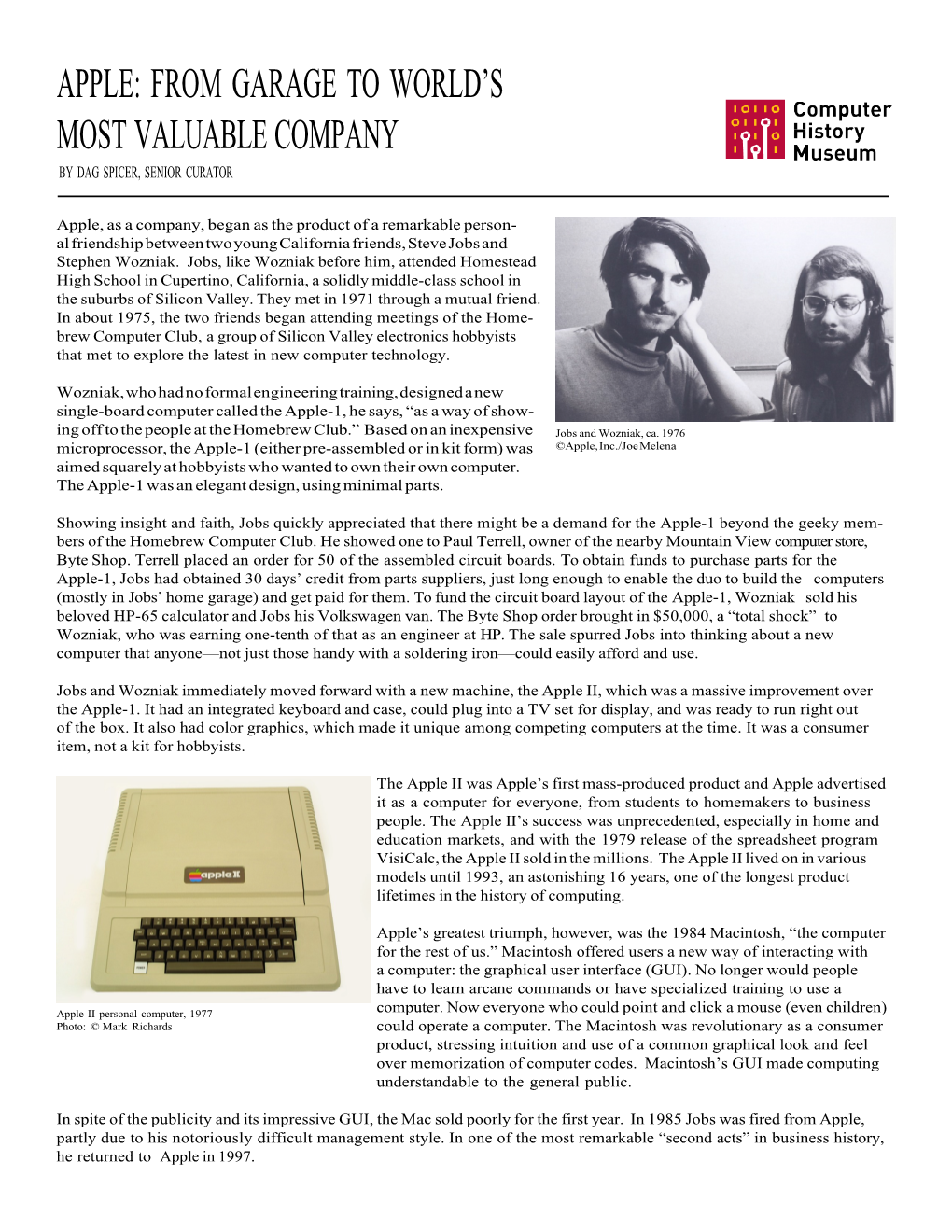

Steve Wozniak was born in 1950 Steve Jobs in 1955, both attended Homestead High School, Los Altos, California, Wozniak dropped out of Berkeley, took a job at Hewlett-Packard as an engineer. They met at HP in 1971. Jobs was 16 and Wozniak 21. 1975 Wozniak and Jobs in their garage working on early computer technologies Together, they built and sold a device called a “blue box.” It could hack AT&T’s long-distance network so that phone calls could be made for free. Jobs went to Oregon’s Reed College in 1972, quit in 1974, and took a job at Atari designing video games. 1974 Wozniak invited Jobs to join the ‘Homebrew Computer Club’ in Palo Alto, a group of electronics-enthusiasts who met at Stanford 1974 they began work on what would become the Apple I, essentially a circuit board, in Jobs’ bedroom. 1976 chiefly by Wozniak’s hand, they had a small, easy-to-use computer – smaller than a portable typewriter. In technical terms, this was the first single-board, microprocessor-based microcomputer (CPU, RAM, and basic textual-video chips) shown at the Homebrew Computer Club. An Apple I computer with a custom-built wood housing with keyboard. They took their new computer to the companies they were familiar with, Hewlett-Packard and Atari, but neither saw much demand for a “personal” computer. Jobs proposed that he and Wozniak start their own company to sell the devices. They agreed to go for it and set up shop in the Jobs’ family garage. Apple I A main circuit board with a tape-interface sold separately, could use a TV as the display system, text only. -

Hardware and Software Companies During the Microcomputer Revolution

Technology Companies Hardware and software houses of the microcomputer age James Tam Recall: Computers Before The Microprocessor James Tam Image: “A History of Computing Technology” (Williams) CPSC 409: The Microcomputer era The Microprocessor1, 2 • Intel was commissioned to design a special purpose system for a client. – Busicom (client): A Japanese hand-held calculator manufacturer – Prior to this the core money making business of Intel was manufacturing computer memory. • “Intel designed a set of four chips known as the MCS-4.”1 – The CPU for the chip was the 4004 (1971) – Also it came with ROM, RAM and a chip for I/O – It was found that by designing a general purpose computer and customizing it through software that this system could meet the client’s needs but reach a larger market. – Clock: 108 kHz3 1 http://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/history/museum-story-of-intel-4004.html 2 https://spectrum.ieee.org/tech-history/silicon-revolution/chip-hall-of-fame-intel-4004-microprocessor James Tam 3 http://www.intel.com/pressroom/kits/quickreffam.htm The Microprocessor1,2 (2) • Intel negotiated an arrangement with Busicom so it could freely sell these chips to others. – Busicom eventually went bankrupt! – Intel purchased the rights to the chip and marketed it on their own. James Tam CPSC 409: The Microcomputer era The Microprocessor (3) • 8080 processor: second 8 bit (data) microprocessor (first was 8008). – Clock speed: 2 MHz – Used to power the Altair computer – Many, many other processors came after this: • 80286, 80386, 80486, Pentium Series I – IV, Celeron, Core • The microprocessors development revolutionized computers by allowing computers to be more widely used. -

From Struggles to Stardom

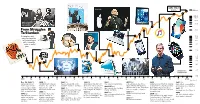

AAPL 175.01 Steve Jobs 12/21/17 $200.0 100.0 80.0 17 60.0 Apple co-founders 14 Steve Wozniak 40.0 and Steve Jobs 16 From Struggles 10 20.0 9 To Stardom Jobs returns Following its volatile 11 10.0 8.0 early years, Apple has 12 enjoyed a prolonged 6.0 period of earnings 15 and stock market 5 4.0 gains. 2 7 2.0 1.0 1 0.8 4 13 1 6 0.6 8 0.4 0.2 3 Chart shown in logarithmic scale Tim Cook 0.1 1980 ’82 ’84 ’86’88 ’90 ’92 ’94 ’96 ’98 ’00 ’02 ’04 ’06’08 ’10 ’12 ’14 ’16 2018 Source: FactSet Dec. 12, 1980 (1) 1984 (3) 1993 (5) 1998 (8) 2003 2007 (12) 2011 2015 (16) Apple, best known The Macintosh computer Newton, a personal digital Apple debuts the iMac, an The iTunes store launches. Jobs announces the iPhone. Apple becomes the most valuable Apple Music, a subscription for the Apple II home launches, two days after assistant, launches, and flops. all-in-one desktop computer 2004-’05 (10) Apple releases the Apple TV publicly traded company, passing streaming service, launches. and iPod Touch, and changes its computer, goes public. Apple’s iconic 1984 1995 (6) with a colorful, translucent Apple unveils the iPod Mini, Exxon Mobil. Apple introduces 2017 (17 ) name from Apple Computer. Shares rise more than Super Bowl commercial. Microsoft introduces Windows body designed by Jony Ive. Shuffle, and Nano. the iPhone 4S with Siri. Tim Cook Introduction of the iPhone X. -

Steve Jobs – Who Blended Art with Technology

GENERAL ¨ ARTICLE Steve Jobs – Who Blended Art with Technology V Rajaraman Steve Jobs is well known as the creator of the famous Apple brand of computers and consumer products known for their user friendly interface and aesthetic design. In his short life he transformed a range of industries including personal comput- ing, publishing, animated movies, music distribution, mobile phones, and retailing. He was a charismatic inspirational leader of groups of engineers who designed the products he V Rajaraman is at the visualized. He was also a skilled negotiator and a genius in Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. Several marketing. In this article, we present a brief overview of his generations of scientists life. and engineers in India have learnt computer 1. Introduction science using his lucidly written textbooks on Steve Jobs made several significant contributions which revolu- programming and tionized six industries, namely, personal computing, publishing, computer fundamentals. His current research animated movies, music distribution, mobile phones, and retail- interests are parallel ing digital products. In all these cases he was not the primary computing and history of inventor; rather he was a consummate entrepreneur and manager computing. who understood the potential of a technology, picked a team of talented engineers to create what he visualized, motivated them to perform well beyond what they thought they could do. He was an aesthete who instinctively blended art with technology. He hired the best industrial designers to design products which were not only easy to use but were also stunningly beautiful. He was a marketing genius who created demand for his products by leaking tit bits of information about their ‘revolutionary’ features, thereby building expectancy among prospective customers. -

The History of Apple Inc

The History of Apple Inc. Veronica Holme-Harvey 2-4 History 12 Dale Martelli November 21st, 2018 Apple Inc is a multinational corporation that creates many different types of electronics, with a large chain of retail stores, “Apple Stores”. Their main product lines are the iPhone, iPad, and Macintosh computer. The company was founded by Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak and was created in 1977 in Cupertino, California. Apple Inc. is one of the world’s largest and most successful companies, recently being the first US company to hit a $1 trillion value. They shaped the way computers operate and look today, and, without them, numerous computer products that we know and love today would not exist. Although Apple is an extremely successful company today, they definitely did not start off this way. They have a long and complicated history, leading up to where they are now. Steve Jobs was one of the co-founders of Apple Inc. and one of first developers of the personal computer era. He was the CEO of Apple, and is what most people think of when they think ”the Apple founder”. Besides this, however, Steve Jobs was also later the chairman and majority shareholder of Pixar, and a member of The Walt Disney Company's board of directors after Pixar was bought out, and the founder, chairman, and CEO of NeXT. Jobs was born on February 24th, 1955 in San Francisco, California. He was raised by adoptive parents in Cupertino, California, located in what is now known as the Silicon Valley, and where the Apple headquarters is still located today. -

NEWSLETTER Computer

NEWSLETTER Computer x ' ' - 4 i■ Volume 3 — Issue 5 August-September 1978 Users GroupBob Reiling Additional Meetings ■ W F -' Scheduled This js a short list of user groups that meet in the Bay Area. No doubt many more exist but I do not Additional meetings of the Homebrew have any inform ation about them. Send me inform a Computer Club have just been scheduled. tion about your group and it will be reported in the The dates are listed in the table in addition N ewsl fetter. "** to previously scheduled dates. You are encouraged to bring your equipment and SOL USERS' SOCIETY (SOLUS) - S.F. Peninsula software for display at the meetings. Chapter meets third Sunday of each month beginning Manufacturers and computer stores are at 1 p.m. at" Stanford Physics Building. Other chapters included in this invitation. Fairchild - throughout USA and Canada. Auditorium has a large lobby area which TRS 80 USERS GROUP - Meets at Radio Shack is well suited for display. One caution, Wednesdays 7:30 p.m. Payne Ave. Radio Shack, however: commercial transactions may not Campbell, (408) 247-5300: Call early in week to con be completed on Stanford premises. firm schedule. 1978 Meeting Schedule AM I PROTO USERS & SW TPC USERS - Meets in 7:00 pm -10:30 pm. Room 210t Brànnon Hall; University of Santa Clara, first Tuesday of month at 7:30 p.m. Date Location September 27 Fairchild Auditorium PET USERS GROUP — President Marvin VanDerKoor October 11 SLAC Auditorium will coordinate group. Request additional meeting November 8 SLAC Auditorium at the next HCC meeting. -

Apple Products' Impact on Society

Apple Products’ Impact on Society Tasnim Eboo IT 103, Section 003 October 5, 2010 Honor Code: "By placing this statement on my webpage, I certify that I have read and understand the GMU Honor Code on http://academicintegrity.gmu.edu/honorcode/ . I am fully aware of the following sections of the Honor Code: Extent of the Honor Code, Responsibility of the Student and Penalty. In addition, I have received permission from the copyright holder for any copyrighted material that is displayed on my site. This includes quoting extensive amounts of text, any material copied directly from a web page and graphics/pictures that are copyrighted. This project or subject material has not been used in another class by me or any other student. Finally, I certify that this site is not for commercial purposes, which is a violation of the George Mason Responsible Use of Computing (RUC) Policy posted on http://universitypolicy.gmu.edu/1301gen.html web site." Introduction Apple was established in 1976 and has continuously since that date had an impact on our society today. Apple‟s products have grown year after year, with new inventions and additions to products coming out everyday. People have grown to not only recognize these advance items by their aesthetic appeal, but also by their easy to use methodology that has created a new phenomenon that almost everyone in the world knows about. With Apple‟s worldwide annual sales of $42.91 billion a year, one could say that they have most definitely succeeded at their task of selling these products to the majority of people. -

Quick Start for Apple Iigs

Quick Start for Apple IIGS Thank you for purchasing Uthernet II from A2RetroSystems, the best Ethernet card for the Apple II! Uthernet II is a 10/100 BaseTX network interface card that features an on- board TCP/IP stack. You will find that this card is compatible with most networking applications for the IIGS. Refer to the Uthernet II Manual for complete information. System Requirements Software • Apple IIGS ROM 01 or ROM 3 with one free slot Download the Marinetti TCP/IP 3.0b9 disk image at • System 6.0.1 or better http://a2retrosystems.com/Marinetti.htm • 2 MB of RAM or more 1. On the disk, launch Marinetti3.0B1 to install the first • Marinetti 3.0b9 or better part of Marinetti, then copy the TCPIP file from the • Hard drive and accelerator recommended disk into *:System:System.Setup, replacing the older TCPIP file. Finally, copy the UthernetII file into *:System:TCPIP 2. Restart your Apple IIGS, then choose Control Panels Installation Instructions from the Apple menu and open TCP/IP. Click Setup con- Uthernet II is typically installed in slot 3. nection... 3. From the Link layer popup menu, choose UthernetII. 1. Power off, and remove the cover of your Apple IIGS. 2. Touch the power supply to discharge any static elec- Click Configure..., then set your slot number in LAN Slot, and click the DHCP checkbox to automatically config- tricity. ure TCP/IP. Click Save, then OK, then Connect to network. 3. If necessary, remove one of the plastic covers from the back panel of the IIGS. -

Chapter 18 Magazines and Newsletters

Chapter 18 Magazines and Newsletters 18.1 ... The Beginning Publication of personal computing articles was initially in electronic magazines such as Popular Electronics, QST and Radio-Electronics. Then came the magazines and newsletters devoted to personal computing and microcomputers. Most of these initial publications were not specific to a particular microprocessor or type of microcomputer. The following are some of the more significant publications. The first publication devoted to personal computing was the Amateur Computer Society ACS Newsletter. The editor was Stephen B. Gray who was also the founder of ACS. The first issue was published in August 1966 and the last in December 1976. It was a bi- monthly directed at anyone interested in building and operating a personal computer. The newsletter was a significant source of information on the design and construction of a computer during the time period it was published. The PCC Newsletter was published by Robert L. Albrecht of the People's Computer Company in California. The first issue was published in October 1972. The first issue cover stated it “is a newspaper... about having fun with computers, learning how to use computers, how to buy a minicomputer for yourself your school and books films and tools of the future.” The newspaper name changed to the People’s Computers with a magazine type of format in May-June 1977. Hal Singer started the Micro-8 Newsletter in September 1974. This was a newsletter published by the Micro-8 Computer Users Group, originally the Mark-8 Group for Mark-8 computer users. Another publication started in 1974, was The Computer Hobbyist newsletter. -

Personal Computing

Personal Computing Thomas J. Bergin ©Computer History Museum American University Recap: Context • By 1977, there was a fairly robust but fragmented hobbyist-oriented microcomputer industry: – Micro Instrumentation Telemetry Systems (MITS) – Processor Technology – Cromemco – MicroStuf – Kentucky Fried Computers • Two things were needed for the personal computer revolution: 1) a way to store and retrieve data, and 2) a programming language in which to write applications. Homebrew Computer Club • March 5, 1975: the Amateur Computer Users Group (Lee Felsenstein, Bob Marsh, Steve Dompier, BobAlbrecht and 27 others) met in Gordon French’s garage, Menlo Park, CA • 3rd meeting drew several hundred people and was moved to the Coleman mansion • Stanford Linear Accelerator Center’s auditorium – Steve Wozniak shows off his single board computer – Steve Jobs attends meetings Homebrew-ed • 21 companies formed: – Apcose Apple – Cromemco Morrow – North Star Osborne • West Coast Computer Faire • Byte magazine, September 1975 • Byte Shop Both: images.google.com And then there was Traf-O-Data • October 28, 1955: William H. Gates III born – father: attorney mother: schoolteacher • Lakeside School: Lakeside Programming Group – Mothers Club: access to time-shared system at GE – Students hired by local firm to debug software – First computer program: Tic-Tac-Toe (age 13) – Traf-O-Data to sell traffic mgt. software (age 16) • 1973, Bill Gates enrolls at Harvard in pre-law. • Paul Allen is in his second year. January 1975, Popular Electronics: Altair • Allen shows -

The History of the Ipad

Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association Volume 2015 Article 3 2016 The iH story of the iPad Michael Scully Roger Williams University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Scully, Michael (2016) "The iH story of the iPad," Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association: Vol. 2015 , Article 3. Available at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings/vol2015/iss1/3 This Conference Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association by an authorized editor of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The iH story of the iPad Cover Page Footnote Thank you to Roger Williams University and Salve Regina University. This conference paper is available in Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association: http://docs.rwu.edu/ nyscaproceedings/vol2015/iss1/3 Scully: iPad History The History of the iPad Michael Scully Roger Williams University __________________________________________________________________ The purpose of this paper is to review the history of the iPad and its influence over contemporary computing. Although the iPad is relatively new, the tablet computer is having a long and lasting affect on how we communicate. With this essay, I attempt to review the technologies that emerged and converged to create the tablet computer. Of course, Apple and its iPad are at the center of this new computing movement. -

Steve Wozniak

Steve Wozniak. http://www.woz.org http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steve_Wozniak http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_box http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_computer Steve Wozniak’s patent: Microcomputer for use with video display. Apple 1 manual. Apple 1 manual (PDF). http://apple2history.org/ http://www.digibarn.com/ http://www.macmothership.com/ http://www.multimedialab.be http://www.mast-r.org Wozniak’s early inspirations came from his father Jerry who was a Loc- kheed engineer, and from a fictional wonder-boy: Tom Swift. His father infected him with fascination for electronics and would often check over young Woz’s creations. Tom Swift, on the other hand, was for Woz an epitome of creative freedom, scientific knowledge, and the ability to find solutions to problems. Tom Swift would also attractively illustrate the big awards that await the inventor. To this day, Wozniak returns to Tom Swift books and reads them to his own kids as a form of inspiration. John Draper explained to Wozniak the Blue Box, a device with which one could (mis)use the telephone system by emulating pulses (i.e. phone phreaking). Although Draper instructed Woz not to produce and especially not sell the gadgets on account of the possibility of being discovered, Wo- zniak built and sold Blue Boxes for $150 a piece. Wozniak met Steve Jobs while working a summer job at HP, and they began selling blue boxes to- gether. Many of the purchasers of their blue boxes were in fact discovered and sure enough John Draper was linked to their use. 1975. By 1975, Woz dropped out of the University of California, Berkeley (he would later finish his degree in 1987) and came up with a computer that eventually became successful nationwide.