ABSTRACT SCHNELL, EUGENE ZACHARY. an Ethnobotany Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chec List Amphibians and Reptiles, Romblon Island

Check List 8(3): 443-462, 2012 © 2012 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution Amphibians and Reptiles, Romblon Island Group, central PECIES Philippines: Comprehensive herpetofaunal inventory S OF Cameron D. Siler 1*, John C. Swab 1, Carl H. Oliveros 1, Arvin C. Diesmos 2, Leonardo Averia 3, Angel C. ISTS L Alcala 3 and Rafe M. Brown 1 1 University of Kansas, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Biodiversity Institute, Lawrence, KS 66045-7561, USA. 2 Philippine National Museum, Zoology Division, Herpetology Section. Rizal Park, Burgos St., Manila, Philippines. 3 Silliman University Angelo King Center for Research and Environmental Management, Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental, Philippines. * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: We present results from several recent herpetological surveys in the Romblon Island Group (RIG), Romblon Province, central Philippines. Together with a summary of historical museum records, our data document the occurrence of 55 species of amphibians and reptiles in this small island group. Until the present effort, and despite past studies, observations of evolutionarily distinct amphibian species, including conspicuous, previously known, endemics like the forestherpetological frogs Platymantis diversity lawtoni of the RIGand P.and levigatus their biogeographical and two additional affinities suspected has undescribedremained poorly species understood. of Platymantis We . reportModerate on levels of reptile endemism prevail on these islands, including taxa like the karst forest gecko species Gekko romblon and the newly discovered species G. coi. Although relatively small and less diverse than the surrounding landmasses, the islands of Romblon Province contain remarkable levels of endemism when considered as percentage of the total fauna or per unit landmass area. -

Review Article Organic Compounds: Contents and Their Role in Improving Seed Germination and Protocorm Development in Orchids

Hindawi International Journal of Agronomy Volume 2020, Article ID 2795108, 12 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2795108 Review Article Organic Compounds: Contents and Their Role in Improving Seed Germination and Protocorm Development in Orchids Edy Setiti Wida Utami and Sucipto Hariyanto Department of Biology, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya 60115, Indonesia Correspondence should be addressed to Sucipto Hariyanto; [email protected] Received 26 January 2020; Revised 9 May 2020; Accepted 23 May 2020; Published 11 June 2020 Academic Editor: Isabel Marques Copyright © 2020 Edy Setiti Wida Utami and Sucipto Hariyanto. ,is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In nature, orchid seed germination is obligatory following infection by mycorrhizal fungi, which supplies the developing embryo with water, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals, causing the seeds to germinate relatively slowly and at a low germination rate. ,e nonsymbiotic germination of orchid seeds found in 1922 is applicable to in vitro propagation. ,e success of seed germination in vitro is influenced by supplementation with organic compounds. Here, we review the scientific literature in terms of the contents and role of organic supplements in promoting seed germination, protocorm development, and seedling growth in orchids. We systematically collected information from scientific literature databases including Scopus, Google Scholar, and ProQuest, as well as published books and conference proceedings. Various organic compounds, i.e., coconut water (CW), peptone (P), banana homogenate (BH), potato homogenate (PH), chitosan (CHT), tomato juice (TJ), and yeast extract (YE), can promote seed germination and growth and development of various orchids. -

Provincial MDG Report

I. History The Negritoes were the aborigines of the islands comprising the province of Romblon. The Mangyans were the first settlers. Today, these groups of inhabitants are almost extinct with only a few scattered remnants of their descendants living in the mountain of Tablas and in the interior of Sibuyan Island. A great portion of the present population descended from the Nayons and the Onhans who immigrated to the islands from Panay and the Bicols and Tagalogs who came from Luzon as early as 1870. The Spanish historian Loarca was the first who genuinely explored its settlements when he visited the islands in 1582. At that time Tablas Island was named “Osingan” and together with the other islands of the group were under the administrative jurisdiction of Arevalo (Iloilo). From the beginning of Spanish sovereignty up to 1635, the islands were administered by secular clergy. When the Recollect Fathers arrived in Romblon, they found some of the inhabitants already converted to Christianity. In 1637, the Recollects established seven missionary centers at Romblon, Badajos (San Agustin), Cajidiocan, Banton, Looc, Odiongan and Magallanes (Magdiwang). In 1646, the Dutch attacked the town of Romblon and inflicted considerable damage. However, this was insignificant compared with the injuries that the town of Romblon and other towns in the province sustained in the hands of the Moros, as the Muslims of Mindanao were then called during the Moro depredation, when a good number of inhabitants were held captives. In order to protect its people from further devastation, the Recollect Fathers built a fort in the Island of Romblon in 1650 and another in Banton Island. -

Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants Used by Ayta Communities in Dinalupihan, Bataan, Philippines

Pharmacogn J. 2018; 10(5):859-870 A Multifaceted Journal in the field of Natural Products and Pharmacognosy Original Article www.phcogj.com | www.journalonweb.com/pj | www.phcog.net Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants used by Ayta Communities in Dinalupihan, Bataan, Philippines Ourlad Alzeus G. Tantengco*1, Marlon Lian C. Condes2, Hanna Hasmini T. Estadilla2, Elena M. Ragragio2 ABSTRACT Objectives: This study documented the species of medicinal plants used by Ayta communities in Dinalupihan, Bataan. The plant parts used for medicinal purposes, preparations, mode of administration of these medicinal plants were determined. The most important species based on use values and informant consensus factors were also calculated. Methods: A total of 26 informants were interviewed regarding the plants they utilize for medicinal purposes. Free and prior informed consents were obtained from the informants. Taxonomic identification was done in the Botany Division of the National Museum of the Philippines. Informant consensus factor (FIC) and use values (UV) were also calculated. Results: Ayta communities listed a total of 118 plant species classified into 49 families used as herbal medicines. The FamilyFabaceae was the most represented plant family with 11 species. Leaves were the most used plant part (43%). Majority of medicinal preparations were taken orally (57%). It was found that Psidium guajava L. and Lunasia amara Blanco were the most commonly used medicinal plants in the Ourlad Alzeus G. Tan- three communities with the use value of 0.814. Conclusion: This documentation provides tengco1*, Marlon Lian C. a catalog of useful plants of the Ayta and serves as a physical record of their culture for the 2 education of future Ayta generations. -

Saint Martin's Biological Survey Report, Bangladesh

ii BOBLME-2015-Ecology-48 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal and development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The BOBLME Project encourages the use of this report for study, research, news reporting, criticism or review. Selected passages, tables or diagrams may be reproduced for such purposes provided acknowledgment of the source is included. Major extracts or the entire document may not be reproduced by any process without the written permission of the BOBLME Project Regional Coordinator. BOBLME contract: FAOBGDLOA2014-019 For bibliographic purposes, please reference this publication as: BOBLME (2015) Saint Martin’s biological survey report, Bangladesh. BOBLME-2015-Ecology-48 ii Saint Martin’s biological survey report, Bangladesh Saint Martin’s biological survey report (Fauna and flora checklist) Under Strengthening National Capacity on Managing Marine Protected Areas (MPA) in Bangladesh (Second part of the BOBLME support in developing the framework for establishing MPA in Bangladesh) By Save Our Sea (Technical partner of the project) 49/1 Babar road, Block B, Mohammadpur, Dhaka 1207, Bangladesh. www.saveoursea.social, [email protected] +880-2-9112643 +880-161-4870997 Submitted to IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural -

5 Romblon Home Depot Brgy

DOLE MIMAROPA - COVID19 ADJUSTMENT MEASURES PROGRAM (CAMP) LIST OF ESTABLISHMENTS ROMBLON No. of Workers Affected No. Name of Establishment Address Male Female Total 1 ST. VINCENT FERRER PARISH MULTI-PURPOSE COOPERATIVE Brgy. Dapawan, Odiongan, Romblon 62 48 110 2 YANNEYES BUILDERS INC Brgy. Gabawan, Odiongan, Romblon 11 7 18 2ND FLOOR CENTRO BLDG., P. BURGOS STREET COR. 1 0 1 3 ALL-DAY-SALE AND GENERAL MERCHANDISE MAGSAYSAY 4 J & C Lucky 99 Store Brgy. Liwayway, Odiongan, Romblon 1 10 11 5 Romblon Home Depot Brgy. Dapawan, Odiongan, Romblon 6 2 8 6 Epiphany School of Peace and Goodwill IFI Learning Institution Inc. Brgy. Dapawan, Odiongan, Romblon 9 24 33 7 Deli Hunter Snack Bar Brgy. Ligaya, Odiongan, Romblon 7 8 15 8 PBY Enterprise Brgy. Liwayway, Odiongan, Romblon 30 8 38 9 CITADEL TRAINING CENTER INC. BUDIONG,ODIONGAN,ROMBLON 0 2 2 10 BATANGAS JNBER TRADING CORP. Poblacion 2, Romblon, Romblon 6 3 9 11 Healthy Bread Bakeshop and Wellness Products Gabawan, Odiongan, Romblon 0 2 2 12 RAMAS-UYPITCHING SONS, INC. Brgy. Dapawan, Odiongan, Romblon 34 12 46 13 SOYAMI PRODUCTS Brgy. Libertad, Odiongan, Romblon 4 3 7 14 Streat Café Brgy. Liwayway, Odiongan, Romblon 0 4 4 15 HAMBIL GENERAL MERCHANDISE AND HARDWARE SUPPLY INC. Brgy. Poblacion, San Jose, Romblon 2 1 3 16 BATANGAS JNBER TRADING CORP. - Lamao Lamao, Romblon, Romblon 4 1 5 17 ARIANA'S ISLAND BAR AND RESTAURANT Poblacion, San Jose, Romblon 14 6 20 18 NOLAN CONSTRUCTION Poblacion, Looc, Romblon 18 1 19 19 NIVERDAY INCORPORATION DOING BUSINESS UNDER SAGIP BRGY. TULAY, ODIONGAN, ROMBLON 1 3 4 20 K TWINS SCHOOL AND OFFICE SUPPLIES Poblacion, Looc, Romblon 1 3 4 21 CARABAO ISLAND GRILL AND RESTAURANT Poblacion, San Jose, Romblon 2 3 5 22 EVERYBUDDY'S OFFICE AND SCHOOL SUPPLIES TRADING BARANGAY IV, ROMBLON,ROMBLON 0 1 1 23 FRIENDSHOPPE POTPOURRI ODIONGAN,SAN ANDRES AND ROMBLON,ROMBLON 0 6 6 24 DC MUNTING PARAISO RESORT Brgy. -

Region Penro Cenro Province Municipality Barangay

REGION PENRO CENRO PROVINCE MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY DISTRICT AREA IN HECTARES NAMEOF ORGANIZATION TYPE OF ORGANIZATION COMPONENT COMMODITY SPECIES YEAR ZONE TENURE RIVER BASIN NUMBER OF LOA WATERSHED SITECODE REMARKS MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Buenavista Sihi Lone District 34.02 LGU-Sihi LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0001-0034 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Boac Tumagabok Lone District 8.04 LGU-Tumagabok LGU Agroforestry Timber and Fruit Trees Narra, Langka, Guyabano, and Rambutan 2011 Production 11-174001-0002-0008 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 2.00 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Agroforestry Fruit Trees Langka 2011 Production 11-174001-0003-0002 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 12.01 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection Untenured 11-174001-0004-0012 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 7.04 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0005-0007 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 3.00 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0006-0003 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 1.05 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0007-0001 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 2.03 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0008-0002 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Buenavista Yook Lone District 30.02 LGU-Yook -

Therapeutic Orchids: Traditional Uses and Recent Advances — an Overview

Fitoterapia 82 (2011) 102–140 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fitoterapia journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fitote Review Therapeutic orchids: traditional uses and recent advances — An overview Mohammad Musharof Hossain ⁎ Department of Botany, University of Chittagong, Chittagong 4331, Bangladesh article info abstract Article history: Orchids have been used as a source of medicine for millennia to treat different diseases and Received 27 January 2010 ailments including tuberculosis, paralysis, stomach disorders, chest pain, arthritis, syphilis, Accepted in revised form 4 September 2010 jaundice, cholera, acidity, eczema, tumour, piles, boils, inflammations, menstrual disorder, Available online 21 September 2010 spermatorrhea, leucoderma, diahorrhea, muscular pain, blood dysentery, hepatitis, dyspepsia, bone fractures, rheumatism, asthma, malaria, earache, sexually transmitted diseases, wounds Keywords: and sores. Besides, many orchidaceous preparations are used as emetic, purgative, aphrodisiac, Salep vermifuge, bronchodilator, sex stimulator, contraceptive, cooling agent and remedies in Vanilla scorpion sting and snake bite. Some of the preparations are supposed to have miraculous Chyavanprash Shi-Hu curative properties but rare scientific demonstration available which is a primary requirement Tian-Ma for clinical implementations. Incredible diversity, high alkaloids and glycosides content, Bai-Ji research on orchids is full of potential. Meanwhile, some novel compounds and drugs, both in phytochemical and pharmacological point of view have been reported from orchids. Linking of the indigenous knowledge to the modern research activities will help to discover new drugs much more effective than contemporary synthetic medicines. The present study reviews the traditional therapeutic uses of orchids with its recent advances in pharmacological investigations that would be a useful reference for plant drug researches, especially in orchids. -

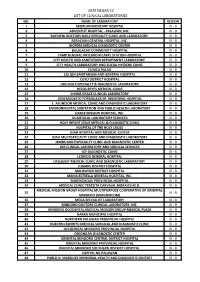

2020 Neqas-Cc List of Clinical Laboratories No

2020 NEQAS-CC LIST OF CLINICAL LABORATORIES NO. NAME OF LABORATORY REGION 1 ABORLAN MEDICARE HOSPITAL IV - B 2 ADVENTIST HOSPITAL - PALAWAN, INC. IV - B 3 BAYVIEW DOCTORS MULTISPECIALTY CLINIC AND LABORATORY IV - B 4 BERACHAH GENERAL HOSPITAL, INC. IV - B 5 BIOFERA MEDICAL DIAGNOSTIC CENTER IV - B 6 BULALACAO COMMUNITY HOSPITAL IV - B 7 CAMP GENERAL ARTEMIO RICARTE STATION HOSPITAL IV - B 8 CITY HEALTH AND SANITATION DEPARTMENT LABORATORY IV - B 9 CITY HEALTH LABORATORY AND SOCIAL HYGIENE CLINIC IV - B 10 CLINICA PALAO IV - B 11 CULION SANITARIUM AND GENERAL HOSPITAL IV - B 12 CUYO DISTRICT HOSPITAL IV - B 13 DBS MULTISPECIALTY & DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY IV - B 14 DELOS REYES MEDICAL CLINIC IV - B 15 DIVINE GRACE CLINICAL LABORATORY IV - B 16 DON MODESTO FORMILLEZA SR. MEMORIAL HOSPITAL IV - B 17 E. ASUNCION MEDICAL CLINIC AND DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY IV - B 18 ENVIRONMENTAL SANITATION AND PUBLIC HEALTH LABORATORY IV - B 19 GRACE MISSION HOSPITAL, INC. IV - B 20 GS MEDICAL LABORATORY SERVICES IV - B 21 HOLY INFANT JESUS MEDICAL & DIAGNOSTIC CLINIC IV - B 22 HOSPITAL OF THE HOLY CROSS IV - B 23 ISIAH HOSPITAL AND MEDICAL CENTER IV - B 24 ISIAH MULTISPECIALTY CLINIC AND DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY IV - B 25 JBMBS MULTISPECIALTY CLINIC AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER IV - B 26 LBR CLINICAL LABORATORY AND MEDICAL SERVICES IV - B 27 LCF DIAGNOSTIC CLINIC IV - B 28 LEONCIO GENERAL HOSPITAL IV - B 29 LIFEQUEST MEDICAL CLINIC AND DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY IV - B 30 LUBANG DISTRICT HOSPITAL IV - B 31 MALIPAYON DISTRICT HOSPITAL IV - B 32 MARIA ESTRELLA GENERAL HOSPITAL, INC. IV - B 33 MARINDUQUE PROVINCIAL HOSPITAL IV - B 34 MEDICAL CLINIC-TERESITA CARVAJAL MORALES M.D. -

Status of Protected Areas in Tablas Island Romblon, Philippines

Journal of Aquaculture & Marine Biology Research Article Open Access Status of protected areas in tablas island romblon, philippines Abstract Volume 1 Issue 2 - 2014 Status of protected areas located at Barangay Budiong, Odiongan and Bunsuran, Maria Mojena Gonzales G, Benjamin Ferrol, in Tablas Island, Romblon, Philippines were assessed last February 22 and 23, 2012.The average live hard coral cover (HC) inside Budiong-Odiongan MPA Gonzales J Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, Western was lower (32%) than that of the outside (45%) but both were categorized into fair Philippines University, Philippines condition. For Bunsuran-Ferrol MPA, HC were the same (30%) and in fair condition. The fish density outside of the Budiong MPA was less than inside, but the biomass of Correspondence: Maria Mojena Gallo Gonzales, Department the outside was higher than that of the inside. This suggests that the fishes outside MPA of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, Western Philippines University, might have larger sizes than those inside Budiong MPA. This maybe brought about by Palawan, Philippines, Email the relatively higher live coral cover outside MPA. Bunsuran-Ferrol MPA has also better fish assemblage status both outside and inside of MPA than the Budiong-Odiongan Received: October 04, 2014 | Published: December 27, 2014 MPA. As for livelihood potential, the number of commercial Families of fish species was seven in the inside of Budiong-Odiongan MPA, while six Families in the outside. The results indicate that the two reefs studied in Tablas Island have undergone high fishing pressures in the past so that it needs immediate nourishment, protection, and management. -

ESGP-PA Student Information Matrix 2Nd

Romblon State University Barangay Liwanag, Odiongan, Romblon STUDENT INFORMATION MATRIX (SIM) Expanded Students' Grants-In-Aid Program for Poverty Alleviation (ESGP-PA) 2nd Semester A.Y. 2017-2018 Cong NAME ADDRESS YEAR AY 2017 - 2018 . LEVEL Dist. NO. HOUSEHOLD NUMBER M.I SEX SCHOOL COURSE Contact person and contact info 2nd Sem Remarks LAST NAME FIRST NAME Barangay Town/City Province (1st, . (1,2,3 (enrolled, dropped, 2nd ,4,5) replaced, deferred, 3rd… graduate) Lone) 1 175901004-4306-00016 AGASCON SHIRLEEN M. Female Camod-om Alcantara Romblon Lone Romblon State University Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Engineering 4 Gina M. Agascon/09078212862 Enrolled 2 175901003-5527-00013 COCHING MAY ANN G. Female Camili Alcantara Romblon Lone Romblon State University Bachelor in Secondary Education 4 Emma Coching/09482367929 Enrolled 3 175901008-2537-00025 DALISAY LEAH MAY M. Female Tugdan Alcantara Romblon Lone Romblon State University Bachelor in Agricultural Technology 4 Analyn Dalisay/09465371806 Enrolled 4 175901008-2677-00036 DALISAY MYRA G. Female Tugdan Alcantara Romblon Lone Romblon State University Bachelor in Secondary Education 4 Leoniza Dalisay/09075233528 Enrolled 5 175901008-2541-00022 FLAVIANO JOSELITO, JR. C. Male Tugdan Alcantara Romblon Lone Romblon State University Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering 4 Elsa C. Flaviano Enrolled 6 175901008-2509-00001 FLAVIANO JULIE ANN R. Female Tugdan Alcantara Romblon Lone Romblon State University Bachelor in Agricultural Technology 4 Magdalina Flaviano/09187078885 Enrolled 7 175901008-2874-00006 FLAVIANO MA. BELEN M. Female Tugdan Alcantara Romblon Lone Romblon State University Bachelor in Secondary Education 4 Sarry Villan/09309311805 Enrolled 8 175901005-2507-00010 FURIO RONAMIE G. -

Network Scan Data

Selbyana 29(1): 69-86. 2008. THE ORCHID POLLINARIA COLLECTION AT LANKESTER BOTANICAL GARDEN, UNIVERSITY OF COSTA RICA FRANCO PUPULIN* Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica. P.O. Box 1031-7050 Cartago, Costa Rica, CA Angel Andreetta Research Center on Andean Orchids, University Alfredo Perez Guerrero, Extension Gualaceo, Ecuador Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA, USA The Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, Sarasota, FL, USA Email: [email protected] ADAM KARREMANS Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica. P.O. Box 1031-7050 Cartago, Costa Rica, CA Angel Andreetta Research Center on Andean Orchids, University Alfredo Perez Guerrero, Extension Gualaceo, Ecuador ABSTRACT. The relevance of pollinaria study in orchid systematics and reproductive biology is summa rized. The Orchid Pollinaria Collection and the associate database of Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica, are presented. The collection includes 496 pollinaria, belonging to 312 species in 94 genera, with particular emphasis on Neotropical taxa of the tribe Cymbidieae (Epidendroideae). The associated database includes digital images of the pollinaria and is progressively made available to the general public through EPIDENDRA, the online taxonomic and nomenclatural database of Lankester Botanical Garden. Examples are given of the use of the pollinaria collection by researchers of the Center in a broad range of systematic applications. Key words: Orchid pollinaria, systematic botany, pollination biology, orchid pollinaria collection,